An investor once gave advice to a man invested in a speculative bubble. “Enjoy the party, but dance near the door.” If you own bitcoin, litecoin, or ethereum, Attack of the 50 Foot Blockchain will make you want to dance near the fire escape. Author David Gerard argues (successfully, I think) against virtually every technology derived from blockchains.

His view can be summarised as “blockchains fail at solving nonexistent problems.” They are speculative and sexy, making them flypaper for con artists, but that’s not the point – even good-faith implementations don’t work.

No major company utilises blockchain-based technology at scale. Ten years after the Satoshi Nakamoto paper, and after five years of loud media hype, cryptocurrency has few visible uses except as an asset (and perhaps it’s already time to remove “except as an asset” from that sentence). In light of this, dramatic fiascoes like the Mt Gox collapse seem more like irrelevant sideshows, distracting from the pervasive pointlessness of the technology. The problem isn’t “suppose your money is stolen.” It’s “suppose it isn’t. Then what?”

The book covers fifteen years of cryptocurrency, from the cypherpunks to the Satoshi whitepaper to the rapidly deflating bubble. It mixes tales of hilarious Wolf of Wall Street-style misadventures with serious analysis of the mathematical and economic weaknesses of blockchains. Bitcoin was supposed to be decentralised. In practice, it is chokepointed by a handful of big exchanges, subjecting their users to increasingly onerous KYC requirements. Bitcoin was supposed to limited to 21 million coins. In practice, any keyboard equipped with Ctrl, C, and V keys can fork the coin, defeating the purpose. Bitcoin’s tamper-proof ledger is frequently cited as a strength, but there are times when you want to tamper with the ledger. Transactions might be made by mistake, for example. The difficulty and risk of bitcoin has all but deep-sixed its small economy of legitimate users, leaving a small number of defiant “HODLers”, convinced that wide adoption is around the corner and things will be better tomorrow.

Gerard also discusses blockchain-based “smart contracts”. Again, they’re hip, and happening, but don’t appear to actually solve any problems with real world contracts, which have always been interpretation (what does “anticipatory breach” mean?) and enforcement (how do you punish anticipatory breach if it happens)?

A famous example: Robin Williams voiced the Genie in Disney’s Aladdin, he stipulated that the genie’s likeness not take up more than 25% of the space on any poster associated with the film (he didn’t want to be typecast as a cartoon character). Disney famously screwed him by making the Genie take up 25% of the space…and making the other characters significantly smaller. Williams joked that they drew Mickey Mouse with three fingers so he couldn’t pick up a cheque. How would putting his contract on a blockchain have helped Robin Williams?

These case studies, and many more, give the impression that blockchains aren’t a viable asset so much as a melon dropping towards the pavement. The book is comprehensive, and well written. Certainly out of date date by now, but that’s hard to avoid – in fast-moving fields, a book can easily be out of date before it reaches publication.

The most interesting parts (which could have been elaborated on more) were the mental psychographies of bitcoin’s users. Cryptocurrencies are a selection filter for unusual brains. The concept is futuristic. The very name sounds Gibsonian. They massage your preconceptions and ideologies: you’re John Galt, Johnny Mnemonic, and . Sadly, they’re also attractive to scammers: the concept is complicated enough that you can bamboozle laypeople, but not so complicated that you can’t fake the jargon with a little practice.

I’ve seen bitcoin evangelists in action. They’re like robots. They probably aspire to be robots – robots that don’t need to eat or sleep or do anything except refresh market depth charts twenty four hours a day. Their arguing styles are almost thrilling in their casuistry and dishonesty. “Blockchains might be used for x” is equated to “blockchains are used for x”, which in turn is equated to “blockchains are the best solution for x”. Sometimes they bust out tu quoque arguments. “Fiat money is imaginary, too!” I don’t follow the logic. All money is worthless…so buy bitcoin?

But they’re making money. Or at least, they used to, and they’re convinced they will again, if they weather the storm of negativity and FUD stirred up by the enemies of freedom. In short, they’ve fallen prey to self deception. “I have invested in bitcoin. This can’t possibly be a bad decision, because this would mean I am stupid. And I’m not stupid, so investing in bitcoin was smart.” I think many of them will look back after the crash and wish they could erase every single post and Tweet they ever typed about bitcoin. But that day is not today.

When the Hindenburg fell, it fell hard, billowing fire across many acres. By then, its failure was obvious, but for the people on board this knowledge came too late to save them. Why not get ahead of the curve? Why not stay clear of the Hindenburg altogether? Attack of the 50 Foot Blockchain has all the information you need not to throw your money into the blockchain bubble, or at least to be very cautious if you do.

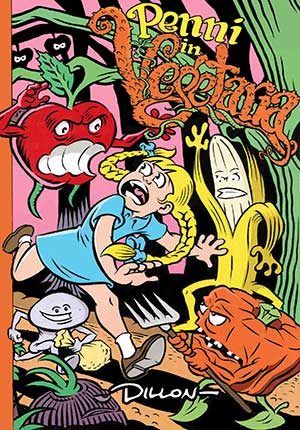

Dillon Naylor is an Australian comic artist, most remembered for Da’n’Dill, which I’m uncomfortable in my ability to pronounce. It’s the verbal equivalent of a missing stair.

Dillon Naylor is an Australian comic artist, most remembered for Da’n’Dill, which I’m uncomfortable in my ability to pronounce. It’s the verbal equivalent of a missing stair.

Da’n’Dill were endemic to Australia’s mid-90s landscape. They appeared in kids’ magazines such as K-Zone, in amusement park showbags, and were syndicated in newspapers. The comic was a disease, infesting every blank piece of paper you could name. Every kid I knew seemed to read them.

The concept was a riff on Mork and Mindy‘s “aliens in suburbia”, but Naylor correctly understood that humor doesn’t come from silliness, it comes from conflict, and he changed the Mindy character into a thin-skinned, teeth-grinding nerd who was constantly having his plans ruined by the dumb, well-meaning aliens.

Naylor’s comics were funny, and seemed even funnier when you were riding a sugar high on the train home from Luna Park. There are legends about casinos that hyper-oxygenate the air to induce euphoria (and compulsive gambling) in their patrons. Naylor had a similar racket going with the under-twelve set.

Penni in Vegetaria is another of Naylor’s works. The setup is as relatable as you can get: it’s dinner time, and Penni doesn’t want to eat her greens. She hides from her parents in a pile of leaves, discovers a spaceship, presses buttons, gets whisked away to a distant planet inhabited by sentient plants, and is soon caught up in a war between rival kingdoms of fruit and vegetables. I hate it when that happens.

The story is kid-friendly, and layered with moralistic overtones. It’s never in doubt that Penny will resolve the war, and will both learn and share some lessons along the way.

But there’s also that typical Naylor subversiveness: such as a visual gag involving a WWII-style internment camp (the detainees are tomatoes, because nobody’s sure what side they’re on!)

Naylor’s art is wonderfully grotesque and expressive. Australian writers (Paul Jennings, Morris Gleitzman, and Andy Griffiths) have always excelled at making twisted and disturbing nightmare fuel that technically isn’t objectionable at all, and Penni in Vegetaria is no exception. Naylor’s specialty? Teeth. They’re huge and scary and jut out like tombstones in nearly every panel. It’s actually pretty frightening. I’ve never worried about being bitten by a comic before.

Penni in Vegetaria is printed on incredibly thin A4 pulp, which might be a result of pro-plant lobbying. It’s rather short and Naylor might have taken the concept further, if he’d had more pages (it’s a disappointment to see the fruit and vegetables fight each other with human weapons, rather than in some funny plant-based way. And I just know that Queen Broccoli was busy planning the Final Solution to the Tomato Problem.)

I’m not sure if there were more Tales from the Ovoid, or whether there’s any connection to the Da’n’Dill universe. Memory tells me that Penni is the sister of the aforementioned nerd, but a re-read revealed that this isn’t true. I also learned that only Da is an alien, whereas Dill is only a mutated parrot. It’s important to know these things.

Although it’s not quite “cult classic” status yet, Penni in Vegetaria is a neat comic, and well worth tracking down. Luna Park closed in the middle of the 90s, but then came back. Naylor’s work is overdue for a similar renaissance.

Mary Shelley wrote a novel called Frankenstein, about a creation overpowering its creator. Unknowingly, she lived out the drama of her story – nothing else she wrote achieved the same fame, and her entire existence is a footnote to Victor Frankenstein. One day, Mary Shelley’s name will be spoken for the last time. Some other day afterwards, Frankenstein’s name will be spoken for the last time. The interval in between might be thousands of years.

Mary Shelley wrote a novel called Frankenstein, about a creation overpowering its creator. Unknowingly, she lived out the drama of her story – nothing else she wrote achieved the same fame, and her entire existence is a footnote to Victor Frankenstein. One day, Mary Shelley’s name will be spoken for the last time. Some other day afterwards, Frankenstein’s name will be spoken for the last time. The interval in between might be thousands of years.

Think of “Frankenstein’s monster” and what comes to mind? A shambling green Boris Karloff, with bolts sticking out of his neck? In the original book, the monster’s skin is yellow, and it has long black hair. The public’s conception of the monster changed with the years, to where it bears little resemblance to Mary Shelley’s creation.

It mutated. It evolved. Mary Shelley called it a monster. But perhaps in modern nomenclature it could be called a virus.

Ellen Ullman’s The Bug is a cyberpunk addendum to Frankenstein. A corporate programmer encounters a bug in his company’s software. This bug has a life of its own, resists his efforts to document and eradicate it, and cripples the program to the point of threatening the company’s big IPO.

At first, it’s called U-1017, as it’s the thousandth and seventeenth bug discovered in the program (although you’d think the programmers would use zero-indexing, making it U-1016). Then, matters become personal, and he calls it Jester. The fight against it takes on mythic proportions.

While he struggles against the bug, his personal life is falling to bits. His wife is unfaithful, the company is screwing him, and his neighbors play music too loud. His failure to defeat U-1017 feels like a referendum against his existence on Earth. Programming is literally the only thing he does. If he fails at that, then what’s left? He liberally comments his code with existential angst.

Ullman adds lots of interesting asides about programming, linguistics, and math. One of the book’s most interesting themes is Conway’s Game of Life: an x-y grid where cell-like automata live, breed, and die in accordance with simple rules. This is introduced as a parallel to corporate programming. There’s a brilliant typographical conceit where the beginning of each chapter contains an iteration of the Game. Clever though this is, it spoils the book. The reader can guess the ending after seeing the final iteration.

(John Horton Conway, by the way, is another Mary Shelley. The Game of Life is so visually intuitive and thought-provoking that it overshadows most of Conway’s other work, much of which he feels is more significant.)

The novel is set in 1984, the age of the Apple Macintosh and the IBM. A lot of bands like Van Halen and Quiet Riot are name-dropped. Women are described as having padded shoulders so frequently that it becomes like a tic. A book like The Bug could never have been written today. The programmer would have posted his code on StackExchange and gotten six solutions by his midmorning break.

The Bug evokes a pretty powerful response from modest ingredients. It’s fascinating, and emotionally affecting. And Ullman doesn’t cheat: we actually do learn the solution to the bug in the end.