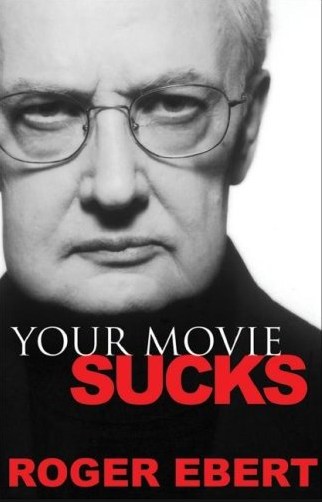

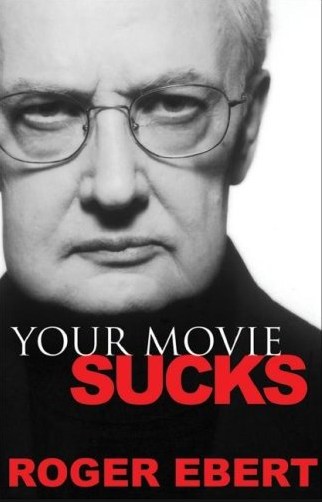

Murray Kempton once said “A critic is someone who enters the battlefield after the war is over and shoots the wounded”, and I’ve always felt the same way. Being a professional critic, even one with a Pulitzer, sounds unsatisfying and wearisome. You’re not a creator. You’re a parasite, feeding off someone else’s work. Even if you help guide a reader to an amazing artist, it’s the artist they’ll remember, not you. This is one of the final books by a man who performed this unfulfilling duty for nearly fifty years.

Murray Kempton once said “A critic is someone who enters the battlefield after the war is over and shoots the wounded”, and I’ve always felt the same way. Being a professional critic, even one with a Pulitzer, sounds unsatisfying and wearisome. You’re not a creator. You’re a parasite, feeding off someone else’s work. Even if you help guide a reader to an amazing artist, it’s the artist they’ll remember, not you. This is one of the final books by a man who performed this unfulfilling duty for nearly fifty years.

Roger Ebert was the best film critic of his time, and maybe one of the best writers, too. He was an optimiser, with an uncanny ability to fit twenty words’ meaning into ten words’ space. He was also a master of the dead-on metaphor. “…like an alarm that goes off while nobody is in the room. It does its job and stops, and nobody cares.” Or “…like taking a bus trip with someone who has needed a bath for a long time“.

It would be too to write this just by copying and pasting quotes from his reviews. Ebert was much more than just a critic, although he was very good at that. Most of the time, anyway. It’s true that in his final years he started playing softball with his ratings – I got the feeling that he loved movies so much that he didn’t have the heart to criticise them by the end. But those years are not found in this book, which collects all his vitriol from 2000 to 2006 or so.

The title comes from a famous incident in 2005, when he slammed a Rob Schneider movie and provoked an embarrassing reaction from said director. There’s two other another confrontations with irate directors mentioned in the beginning, then it’s on to the reviews. Ebert watched about 500 movies a year, and was indiscriminate in his taste. There’s underground art films, and Hollywood blockbusters, and even childrens’ movies.

The book’s worth reading as a sample of Ebert’s writing, but it’s also an interesting exhibit of the art of criticism. Ebert was perfectly happy to watch a movie he didn’t understand, or one that wasn’t aimed at him. He’d simply describe his reaction, and let that suffice as a review of the movie. As he himself said, “Even when a critic dislikes a movie, if it’s a good review, it has enough information so you can figure out whether you’d like it, anyway.” Although at one point (the review of the first Scooby-Doo movie) he just throws up his hands and tells you to go read someone else’s review.

Ebert was a powerful writer and a clever man, but I wonder whether he regretted any of this. He tried his hand at making movies in the early days. What if he’d stuck at it? He has a good understanding of filmmaking and storytelling, but whether that translates to actual cinematic success is anyone’s guess. Many of these reviews are better than the movies that inspired them, but they probably won’t be remembered as long – if at all. As I said, it must be frustrating being a critic. You’re like a eunuch guarding the sultan’s harem – you know all about it…and you can’t do it.

The eighth Redwall book is the critical moment where the series faults – which are many, and present from the beginning – finally pull it down. Jacques provides us with some exciting fight scenes and an exotic setting by way of apology, but the story is a mess. The villain’s motives make no sense, a huge number of pages are inconsequential to the story, and the heroes get helped by author’s convenience so often that they seem to have Brian Jacques on pager.

The eighth Redwall book is the critical moment where the series faults – which are many, and present from the beginning – finally pull it down. Jacques provides us with some exciting fight scenes and an exotic setting by way of apology, but the story is a mess. The villain’s motives make no sense, a huge number of pages are inconsequential to the story, and the heroes get helped by author’s convenience so often that they seem to have Brian Jacques on pager.

The setup is good. Several valuable “Pearls of Lutra” are brought to the Abbey and hidden by a mutinous vermin, who then dies, leaving their location unknown. The vermin’s friends come looking for the Pearls, and when they can’t find them they abduct the Abbott of Redwall and hold him to ransom. Mattimeo’s son and a group of friends give chase to the retreating vermin, and their search for the Abbott takes them to the tropical island of Sampetra – controlled by the tyrannical pine marten Ublaz, who needs the pearls to accomplish…what?

If there’s any significance to the Pearls, it’s not explained. They’re not magical pearls. There’s quite a big deal made about the mice of Redwall looking for the Pearls (cue 10+ tedious chapters of mice deciphering clues), but exactly what this will accomplish is similarly not explained. They have no boat, and no way of getting the Pearls to Ublaz. The Pearls are a MacGuffin but they feel curiously out of place in this book. The kidnapped Abbott is what propels the story forward, never mind a pointless search for buried treasure.

The Sampetra scenes are fun, with the warring and realpolitiking between Ublaz’s warriors being more interesting than the main story. Jacques writes the most interesting villains in the world, while his heroes are boring.

The fights are, as usual, well done, but the heroes have it too easy. A dreadful thing called “plot immunity” is in play here, with Jacques not wanting to kill or hurt any of his named characters, so he has them fight stupid, ill-prepared, unsuspecting dolts. Where’s the tension? Is one of the main characters even going to break a nail in this quest? A boy scout troup could have rescued the Abbott.

The characters make nonsensical decisions, get jerked this way and that by careless yanks of the plot, and the result is a story that doesn’t make sense. There’s no point in the mice collecting the pearls, I have no idea why Ublaz even wants the pearls, and plan to rescue the Abbott only works by writers’ fiat: Jacques stacks the deck so that they can save the day by lucky and unlikely fluke.

The Redwall books that came after this resemble the gag in Monty Python and the Holy Grail, where the king keeps building a castle and it keeps collapsing into a swamp. Jacques never recovered his old power until the day he died, and his most famous series decayed into something almost unreadable. To be honest, even the early Redwall books aren’t that good. They’re best read when you’re a child – so that you don’t notice all the parts held together with Sellotape.

Peter Sotos’s early zines have pictures of ejaculating penises juxtaposed with pictures of missing children. Pure #1 and #2 were shocking, but also educational: front of house seats to a society where Rota Fortunae crushes even the smallest, the most innocent, and the least deserving. Rota Fortunae soon crushed Sotos, too – in 1986 he was charged and convicted on possession of child pornography. This book is part fiction, and part descriptions of his arrest.

Peter Sotos’s early zines have pictures of ejaculating penises juxtaposed with pictures of missing children. Pure #1 and #2 were shocking, but also educational: front of house seats to a society where Rota Fortunae crushes even the smallest, the most innocent, and the least deserving. Rota Fortunae soon crushed Sotos, too – in 1986 he was charged and convicted on possession of child pornography. This book is part fiction, and part descriptions of his arrest.

Pure was disturbing, and parts of it had a hero-worshipping quality that I didn’t especially care for (“The tape recording of the torture is remarkable. Although much is inaudible, and it is certain that much more took place than what is on the tape, it is still a great joy to hear – Brady’s mastery is clearly in evidence.”), but what happened to Sotos doesn’t feel right.

What he does is not morally different to what a news channel does. He exploits human misery, and so does ABC. He just happens to be direct, rather than mincing and prevaricating and pretending to be above it all. Tool describes a telling event. “The front cover of Pure #2 was an extreme close-up of a child’s hairless cunt being spread open by an adult. The night of my arrest, the three main networks in Chicago used me as their lead story, and they all showed close-ups of the cover.”

The first story is written in the second person, and consists of a psycho’s one-sided talk with (apparently) a kidnapped child. Cruel games and Faustian bargains ensue. There’s nothing but dialog in this story, and we’re left to imagine what’s happening to the child in between the kidnapper’s words.

The second story takes us on a exploration of inner-city prostitution, except it’s from the view of a laughing and jeering punter instead of a well-meant liberal documentarian. I like how Sotos writes from the perspective of the bad guy. Normally people writing from “the other side” do so mawkishly, as if they’re trying to make us aware that they’re not really like this in real life. Sotos relishes the role. “Eight” is framed as a sympathy letter to a mother who has lost a daughter, but midway through it changes into something unwholesome and disturbing.

In “Five”, Sotos takes it upon himself to educate us about kiddie porn. Porn featuring young babies, apparently, is not very interesting. The real kicks come from kids who are old enough to have some awareness of what’s happening. In the 80s, the media branded Sotos a pedophile. I’m wondering that he might be something worse than a pedophile. All a pedophile wants is to have fun. But what kind of neurosis would drive a purportedly normal man in his 20s to collect kiddie porn instead of postage stamps?

Superficially, I can understand the appeal of this kind of atrocity tourism. Innocence traduced makes for quite a spectacle, and Tool collects a lot of it. But I’m not convinced that’s the real reason. Sotos has published dozens of books in a career spanning thirty years, and for him it seems not a hobby but an obsession. Anyone will stop for a few seconds to rubberneck a car crash, but Sotos looks far longer and harder than most people…and inevitably, he ended up in a crash himself.

Murray Kempton once said “A critic is someone who enters the battlefield after the war is over and shoots the wounded”, and I’ve always felt the same way. Being a professional critic, even one with a Pulitzer, sounds unsatisfying and wearisome. You’re not a creator. You’re a parasite, feeding off someone else’s work. Even if you help guide a reader to an amazing artist, it’s the artist they’ll remember, not you. This is one of the final books by a man who performed this unfulfilling duty for nearly fifty years.

Murray Kempton once said “A critic is someone who enters the battlefield after the war is over and shoots the wounded”, and I’ve always felt the same way. Being a professional critic, even one with a Pulitzer, sounds unsatisfying and wearisome. You’re not a creator. You’re a parasite, feeding off someone else’s work. Even if you help guide a reader to an amazing artist, it’s the artist they’ll remember, not you. This is one of the final books by a man who performed this unfulfilling duty for nearly fifty years.