I get out of my car after a long, hard, and black day at work. I can’t wait to turn over my paycheck to my wife. We divide household duties 50-50: I earn the money and she spends it. It gives me pride to be a provider figure. The more money I give her, the more she’ll respect me.

My sedan is a mid-grade Asian import. I’ve put a strategic Biden/Harris bumper sticker on it to reflect my political stance. Frankly, if you’re not outraged by what’s happening, you’re not paying attention.

I approach my house. Like the car, it’s tasteful, if understated. Don’t be fooled, though. Inside this house, passion runs like a raging river. Believe me, I’d know – sometimes my wife lets me watch.

I open my front door. Bizarrely, it swings outward, hitting me in the face. It’s like the door isn’t even aware that I’m there. This is the nature of my existence. My family relies on me, I am the only gainfully employed person in the building, and yet often I’m treated like I’m invisible. That’s fine. I don’t need a medal. In any clock, the most important gears are hidden from view.

I enter, and find my infant son Tyrone Jr crawling around on the floor. That won’t do. He might crawl out of doors and get run over by a car or eaten by a dog. The neighbours whisper about TJ, but I don’t listen. Yes, he has a darker skin color than me, and yes, he has less of my genetic material than you’d expect from the terms “my” and “son” but a true family overcomes obstacles like that. When you think about it, being willing to raise another man’s baby makes me even more of a dad.

Honestly, there’s a lot resting on my narrow, sloped, scoliosis-afflicted back. I’m the breadwinner. I cook and I clean. I sometimes feel unappreciated by my family, but I know it’s mostly in my head. I’m important and respected. Truly. Why else would they allow me to live with them?

In mirrors throughout the house, I catch glimpses of myself. I am making the “soyface“, an open-mouthed expression of childlike delight commonly seen among emasculated men as they mindlessly consume media such as Star Wars and Marvel movies. Did you see The Rise of Skywalker? I did. Barely. It was hard to see the screen past my permanently clapping hands.

Outside my house, I hear a schoolbus shifting gears. My other son DeShawn must have come home from school. He’s twelve, and aspires to be a rapper. Once, I told him he’s not a rapper. He said that I’m not his daddy. That stung, but I just smiled. With a quick wit like that maybe he’ll accomplish his dream. I just wish he’d stop stealing my Funko Pops. They’ll be worth a lot of money someday. They’re collector’s items. I know this because the company selling them said they’re collector’s items.

I go upstairs, and find my wife alone with TJ and DeShawn’s biological father, Tyrone Senior. He is a large, muscular black man with an active arrest warrant in his name. I am outraged to find them alone. How dare they? …Won’t they at least allow me to prep the bull?

Apparently that’s not going to happen today. Tyrone tells me to hand over my paycheck and then leave. I ask him how much he wants. He says “all of it”. I guess I haven’t acquired enough good boy points with my wife. I hesitate, Tyrone asks if we have a problem, and I quickly say no. I’d never fight him. He might hurt his knuckles on my face. Anyway, it takes the bigger man to walk away from a confrontation.

Also, I bought a game on Steam called “Cuckold Simulator”. I haven’t played it yet but when I do I’ll tell you what it’s like.

Binding is 10 years old. Aside from the parts that are 45 years old. And also aside from you, the player (I don’t know how old you are).

It’s a slick modern update of the top-down dungeon crawlers people played on mainframes and PLATO systems in the 70s. The classic “roguelike” (as such games were called) consists of an ASCII text world (with your character generally represented by an @), in which you explore dungeons, buy spells, and whack kobolds. They’re one of the oldest game genres and remain influential today – games as varied as Legend of Zelda and Ultima and Diablo could be considered postmodern roguelikes.

The genre’s appeal? Randomness. Early computers had limited data storage and it was actually easier to generate random worlds on the fly using BSP trees than it was to store level data. This also made the games heavily replayable – no two runs of Dungeon or Hack would ever play out the same way – and as Skinner’s 1950s work on operant conditioning demonstrates, randomness itself is addictive. What loot will the next monster spawn? Kill it and find out. Every single fight becomes like Christmas.

Binding is an ugly, degenerate roguelike at heart. You control Isaac, your mother has been commanded by God to sacrifice you, and so you hide from her in the basements beneath your house, which are full of monsters, weapons, health, and other items. If you play well, you gain power, uncover secrets, and perhaps turn the tables on your mom. If you play badly, your cat inherits your loot.

The game is both shallow and deep. While the gameplay loop is simple enough to describe in a sentence – keys open doors, bombs blow up obstacles, killing a boss lets you descend to the next level of the dungeon – the game has hundreds of different items, and it takes a while to learn what they all do. I recommend playing Binding with the Wiki open in another window so you can easily reference the thing you’re about to pick up. It’s often not the case that a pickup will be an unalloyed good – a lot of them have stings in the tail, such increasing your damage while reducing your bullet speed, or giving you extra firepower in exchange for one of your hearts. The game’s loot is also complex in how it interacts with itself. For example, the Cricket’s Body increases your weapon’s rate-of-fire, but this becomes useless if you also have Brimstone equipped, which replaces your weapon with a charge-up beam. A lot of stuff in Binding is situationally good, helping you in only one kind of fight.

Binding is unforgiving. A single wrong choice (such as wasting your last key on the wrong door) can cripple your run. Want to save? You can’t. Want to back out of a losing boss fight? You can’t. You generally don’t know what’s behind the next door – it could be six coins and a heart, or a mini-boss that will stomp your duodenum into the afterlife. This is a 2010 game designed with a 1980 mindset: the player must be abused so that he’ll become a man.

The game’s randomness can make it frustrating as well as interesting. It’s easy to get “RNG screwed” – if you only get useless and unhelpful items from the first couple of floors, soon you’ll be fighting high-level bosses using your starting weapon, which isn’t fun. And certain items seem pretty overpowered. The Unicorn’s Horn can be abused to insta-win every boss fight in the early game, except for Gurdy and Mom. But that’s also part of the appeal, in a weird way. No matter how dire things look, at any moment you might get a god-tier loot drop.

The art style is cute and gross – very “kawaii-gore”. The sound effects are downright disgusting. I don’t know how long the developer spent recording the gurgles and splutters of dying bronchitis patients but hopefully he wiped down the microphone afterwards. The monsters are revolting slimeballs that look like the internal organs evolution mercifully doesn’t allow us to see. Binding has a mid-2000s flash quality (I was overwhelmed by nostalgia by the sight of the Newgrounds logo), and the art assets were clearly designed with an eye towards modding, allowing users to extend the game with their own monsters and items. This is another strength of the roguelikes, which were so basic and minimalistic that it was very easy to spin off a fork of one and turn it into whatever you wanted.

The game draws inspiration from the Biblical tale of Abraham’s “akedah” (or binding) of his son for sacrifice. It seems to be the answer to the question “what did Isaac think of this? And suppose he resisted – what would have happened?” Although religious issues inform the game’s content somewhat, Binding mostly uses Judeo-Christian imagery the same way Hideoki Anno’s Neon Genesis Evangelion does – as a repository of cool and interesting stuff.

The Binding of Isaac is probably one of those games you either play for five minutes or five years, with little middle ground. It’s definitely challenging and “deep”. There’s no shortage of stuff to do, or ways to do it. It’s an overall nice throwback to classic gaming, and Kryptonite for people who save-scum through every game.

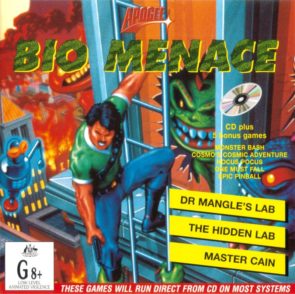

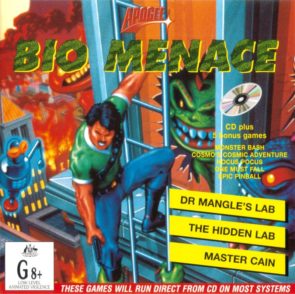

A 1993 platform game programmed for DOS by Apogee’s Jim Norwood, who went on to develop Shadow Warriors, Heroes of Might and Magic V, and that cherished classic Third Example Goes Here. You control a porn-mustachio’d spec force operative named (I fear) Snake Logan, who has crash-landed in a mutant-infested city and must etc.

Platform games belong to either the “jump around and collect stars” Mario school or the “shoot guns and blow shit up” Contra school. Bio Menace is unapologetically the latter: it ranks as among the most violent Apogee titles, with monsters dying in explosions of pixelated blood and body parts. This clashes with their visual design, which is “Teletubby crossbred with Barney the Dinosaur”.

Bio Menace looks a lot older than it is. Slated for a 1991 release, it was delayed for two years due to engine modifications, and in 1993 it looked as dated as glam metal. The graphics are 16-color EGA, and the backgrounds don’t parallax-scroll. At least it ran smoothly. I recall being able to play it on Windows XP, although I don’t think it works on any 64-bit operating system.

The game was a competent blend of puzzle-solving (a laser forcefield blocks the way! Can you find the key to disable it?) and hallways filled with monsters to gun down. It had a nice sense of place – the first level in particular is a realistic urban environment littered with bodies and wrecked cars.

Bio Menace tries to create a believable world. Completing levels is just shorthand for “rescuing civilians”. Reaching high places means finding a ladder or riding an elevator, instead of jumping 30 feet. Health powerups and keys are usually found in places that make logical sense, like lockers and cabinets.

This part of Bio Menace hasn’t aged. In fact, it anticipates the future of gaming. The arcades were going away, and the industry was pupating into the next stage of its life: immersive experiences dependent on technology and sensory realism. Bio Menace, with its stupid monsters and EGA pixels, is far from immersive. But playing that first level, with its eerie post-apocalyptic vibe, you can see that the winds are starting to change. For better or worse, games would soon start trying to be movies.

There’s even an effort made at narrative. When you rescue a civilian, Snake Logan has a little tete-a-tete with them, with dialog as amazing as you’d expect (“I’m gonna dust that little dweeb! He can’t do this and escape!”)…hey, at least it’s only the second worst-written videogame about a spec forces operative called Snake, am I right ba-dum tisshhh hurr hurr.

It exemplifies Apogee’s approach: funnel out cheap (and cheaply made) games under a “shareware” business model. You got to play the first 30% of the game for free, and since that 30% typically contained 80% of the game’s actual worthwhile content, this was a pretty good deal. But it did lend itself to disposable experiences, and games that were copy-pastes of some other popular title.

Bio Menace is a minor game, without the arthouse pretensions of Eric Chahi’s Out of this World or the rotoscoped professionalism of Jordan Mechner’s Prince of Persia. It probably made some money, and even if it didn’t, it surely wasn’t a big red stain on Apogee’s balance sheets. Bio Menace is like throwing ten cents down on a roulette spin. Is it worth playing now? No, unless you’re a fan of “ARE YOU A BAD ENOUGH DUDE TO RESCUE THE PRESIDENT?”-style shlock.