Doom didn’t receive a proper retail release for a long time. For years, the correct way to get the game was to log on to ftp.uwp.edu and stay up all night downloading it on your 14.4k modem. This wedded the game to early internet culture: the idea of buying Doom in a store seems strange, like viewing a Pre-Raphaelite work of art on an iPhone.

Regardless, Doom mission packs of varying quality/legality appeared on shelves and many included a DOOM.EXE, thus making them a handy way to get the game if you weren’t on Al Gore’s information superhighway.

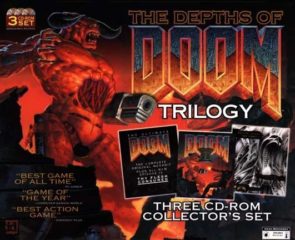

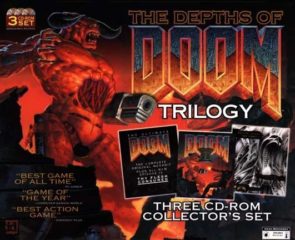

1997’s Depths of Doom was one of the last. It contains the original games (Doom + Thy Flesh Consumed + Doom II), plus DWANGO, plus Windows executables (playing at 640×480 was cool back in the day, although obsolete in an era of GZDoom). It also has Master Levels, a 21-level set that are generally superior to the originals in quality (aside from the shit joke level with fifty Cyberdemons shooting at you).

The second disc contains Maximum Doom, which was ~1800 fan-made levels downloaded from the internet. Shovelware. There’s no quality control: some levels crash, most suck, some are actually for different games like Heretic and Hexen, and some are graphical and audio mods containing content from the Simpsons or Monty Python, making the entire release is technically illegal.

I enjoy playing Doom wads. They’re historical documents from the pre-Google (<1995) internet, or the at least the part of it frequented by teenage boys. You see their fascinations spread out like a mandala: Arnold Schwarzenegger, Beavis and Butthead, porn stars who are now old enough to be grandmothers. If there’s a soundtrack, it’s probably a midi of Metallica or Pantera.

Some of them invite you into their lives in small but touching ways: designing levels based on their house or their mall or their school (that one didn’t age well). I’m fascinated by how many of these uploaders include text files telling you how to contact them…including their real names, and phone numbers, and street addresses.

Was the internet less nasty in 1993? Or were kids stupider?

On Oct 15, 2019, a video was uploaded to Youtube. It did not set the internet on fire, because most of the internet is actually deep-sea cables that are underwater, but it did provoke discussion.

Riot Games, creators of League of Legends, was working on an FPS game. It was called Project A.

The video was stuffed with technical buzzwords (“server tickrate,” “peeker’s advantage”), and although the gameplay footage didn’t dazzle, the comp-gaming focus gained the attention of the coveted “20 gallon piss bottle” demographic. Could this finally be it? That mythical game with priorities beyond selling $20 character skins to Little Timmy No-Thumbs? A game that actually caters to hardcore, competitive players?

Project A was soon basking in (totally undeserved) kudos as the savior of the industry. Apparently claiming you’ve solved peeker’s advantage (the unintended consequence of internet lag that causes players making a move to have an advantage over defenders) is tantamount to actually solving peeker’s advantage, and numerous pro gamers publicly announced that they’d switch to a game they hadn’t played a single second of. References to the game became common in Twitch and Twitter profiles.

The feeling was that with the massive development firepower Riot Games possesses, Project A simply couldn’t fail.

Now the game is 1) released and 2) called Valorant. My feelings are mixed.

The game makes no attempt to disguise the fact that it’s a CS:GO clone. It’s five versus five – a team of attackers against a team of defenders. You buy guns with money you earn from killing people. A highly sophisticated user-interface streamlines the in-game economy, so that “rich” player can easily buy and drop gear for a poor teammate.

Valorant is class-based and character-driven, as is the trend these days. Sova wallhacks, and Viper does area denial. This isn’t as big a change from CS:GO as it might appear – although some characters (like Jett, who is highly mobile; or Raze, who brings some old-school Quake 3 nade jumping back into the mix) flip the gameplay in a new direction, for the most part it’s just a different way of having smokes, molotovs, and so on.

The gunplay works the way CS:GO‘s did, except more so. Moving is good. Shooting is good. Shooting while moving is bad. To hit shots in this game you have to be a turret, as any movement causes shots to wildly flick out ten feet from your crosshairs. Winning gunbattles in this game is less about where you’re shooting than where you’re shooting from: everyone’s jockeying for stable, defensible angles that provide maximal sightlines and minimal exposure. Valorant specialises in tense, white-knuckle moments where both you and the enemy are about to roll the dice and peek around a corner.

Unfortunately, “roll the dice” is indeed the operate phrase, as fights in Valorant have a heavy random element due to inconsistent recoil patterns. This screenshot (taken by Diegosaurs) reveals what you’re up against:

Look at how different the bursts are, and remember that this is a game where you two-tap people with virtually any weapon. Getting the first recoil pattern versus the third could mean the difference between life or death. FPS games should be “git gud, noob”. They should never be “git lucky, noob”. This is a huge issue. I couldn’t find a way to make my tapfires more reliable, no matter how much I tried.

Issues with recoil aside, the game also gets a lot of stuff right. Movement and “gunfeel” is excellent. I liked how you can move around while in the buy menu. CS:GO has a kind of stop-start rhythm. Action. Then downtime. Then action. Then downtime. Valorant’s gameplay feels more of a piece.

The weapons are also great: ranging from pistols to massive, Schwarzenegger-worthy LMGs for big spenders. Wall-penetration is a factor: sometimes it’s smart to forget about angles and just turn a wall into swiss cheese, and the game’s visuals are clear enough to know when you can do that.

Graphically, the game left me cold. As mentioned before it looks similar to Team Fortress 2, right down to its use of Gooch Shading (where models are shaded along a hot-colour/cold-colour axis instead of light-to-dark). Visually, this results in a game that’s colourful but cheap-looking. Arms wave like slabs of putrescent plastic.

…But perhaps in a competitive FPS you really want flat. Valorant is made for players who dial all their graphics settings to low anyway to squeeze out an extra 3 frames per second. Its playerbase would probably be satisfied if all the models were placeholder rigs from Blender, just so long as the hitboxes were balanced. But if your selling point over CS:GO is style, Valorant needs more of it. Everything unrelated to gameplay is stunted and abstracted away. Here’s what trees look like in a triple-A game released in 2020, by the way.

As with much of Valorant’s design, it doesn’t make mistakes, it makes choices. Choices that will alienate many players, as they have me.

I sort of enjoy a focus on content, rather than an abstract skeleton of a game that will hopefully have flesh later. The character-based element draws comparisons to Overwatch, Apex Legends, and League of Legends. Valorant is worse in that area than any of those: the content side of the game is so bland and threadbare that I wonder if F2P was the right business model. The game hopes to support itself with cosmetics…for characters who look bland and who you don’t care about.

Whatever, though. The game’s boosters are probably correct. Valorant is the new paradigm and there is not a chance it will fail. I probably won’t play it again.

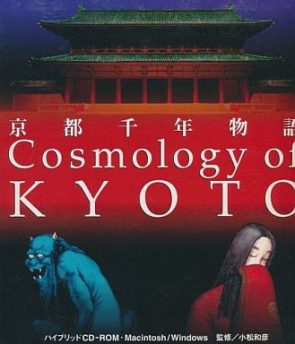

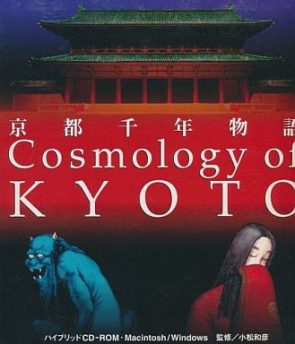

Look up “unique” in the dictionary and you’ll see Cosmology of Kyoto. Only if you use a special dictionary, though. One that has “unique” defined as Cosmology of Kyoto.

Released in 1993, it was sold as a game and is more accurately described as an interactive work of art. It’s moody, confusing, dark, and stylized. You could put it in a class with Dark Seed, Bad Mojo, and Haruhiko Shono’s collective work; games that aren’t remembered with much love but are still remembered.

How did it achieve rapid (if fleeting) fame? Via a technique I call “through the Mac-door”. By 1993, The Macintosh was losing favor as a platform for gaming. A dwindling market share and Apple’s apathy towards gaming had turned it into a dumping ground for “edutainment” dribble and ports of obsolete PC titles, and the occasional original Mac game (even if was a “””game””” wrapped in numerous air quotes) would make waves just because there wasn’t much to choose from.

Without fail, some marketing genius would notice the hype and wrongly conclude that the game was amazing and needed to be rushed to DOS, Windows 3.1, Windows 95, Amiga, and your kitchen toaster right goddamn now, usually with tragic results. If shitty games were AIDS, the Macintosh was a HIV infected needle in DOS’s perineum. But odd games entered the DOS ecosystem through the Mac, too. Games seemingly made in a fever dream or on drugs. This is one of them.

Cosmology of Kyoto takes you on a morbid journey through the Japanese middle ages. Heian-era Japan is now mostly associated with court writers like Murasaki Shikibu and Sei Shonagon, but Cosmology has little time for the courts: it’s focus is the streets and gutters, and the plight of the common folk. Supernatural monsters pose an omnipresent threat.

You create a character before you can play, choosing between “Single” or “Married” and between “Male” or “Female” (you can already tell we’re not in modern Japan because there’s no “Trap” or “Catgirl”). You can also change your facial features, although I didn’t have much luck in not making myself look like a dyspeptic Vladimir Putin. You’re also naked, but fear not: just like in real life you’ll soon find a rotting corpse whose clothes you can steal.

You wander the land, interacting with stuff using a classic “hotspot” based point-and-click interface. You talk to Buddhist monks, samurai, common folk, children, and demons. I died pretty fast: a pissed-off samurai cut off my head, and my soul went to hell.

Another historical aside: adventure games were split at the time in how they handled death. There was the Sierra style (failure = instant death = game over, encouraging the player to plan their actions carefully) and the LucasArts style (you couldn’t die, encouraging the player to experiment and do as many things as possible).

Cosmology charts a third path: you can die, but if you play your cards right you can escape hell and be reincarnated back into the main game. Which you’ll want to, because hell’s pretty bad. The game’s art style has a strong ero-guro influence, with lots of graphic and grotesque imagery. Many Mac titles are for kids. This one isn’t.

By now, Cosmology’s true purpose becomes clear: explaining Buddhism to the gaijin.

I’ve seen people claim that the game has no point, or cannot be finished. Neither is true. You win Cosmology of Kyoto by discovering the source of the demon infestation (I think at the Imperial Palace), and gaining enough karma to break the cycle of death and rebirth. Kind acts like donating money to beggars increase your karma. Swordfighting and stealing decreases it. If you have too much negative karma, you’re reincarnated as a dog when you escape hell.

This emulation of Buddhist spirituality makes it comparable with western RPGs such as Ultima IV, although there’s also a dark, sinister “Tachikawa-ryu” aura of sex and death that’s classically Japanese, and completely missing from Richard Garriott’s famed series.

If esoteric spirituality isn’t your thing, there’s a wealth of historical depth to Cosmology. The game comes with a full encyclopedia of Japanese history and folklore, and the map is a near perfect recreation of Heian-kyo. I guess Cosmology is a kind of backdoor “edutainment” title, fulfilling the Macware stereotype. Maybe this is another reason for its surprising (if short lived) popularity: it’s a cultural experience. A tech support experience, too. As with many classic adventure games, the hardest puzzle in 2020 was getting it to install and run.

Is it worth playing? I don’t know. I think these sorts of weird-ass games are more fun to be aware of than to actually dive into. I don’t need to go to hell: knowing it exists is enough.