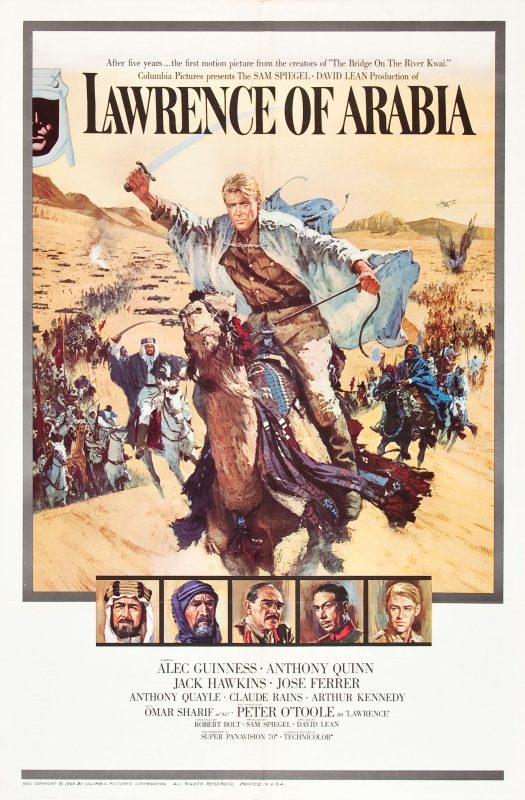

Lawrence of Arabia depicts what was nearly the birth of the modern Arab state, but it’s shot like the end of history. The movie is apocalypse-sized; as if it expects to the last one ever filmed. Everything is huge and grand and excessive – the setting, costuming, score, running time, everything. It thunders over the senses like a train.

It’s an epic about TE Lawrence, as interpreted by Peter O’Toole and largely derived from Lawrence’s own prolific writings. It paints a picture of a freak, a misfit, a uniquely-shaped gear who fell into the engine box of history and miraculously slotted into place, allowing world events to turn. I don’t have much interest in its factual accuracy. Movies aren’t Wikipedia articles.

Lawrence of Arabia starts at the end: with Lawrence’s death in 1935. We see a media frenzy around the dead man, a jostling clash of claim and counterclaim. A great hero? An exhibitionist? Everyone’s comparing puzzle pieces of the deceased man, but none of them match. We sense that Lawrence hasn’t left much of himself behind.

Then the film cuts back in time to 1916, with Lawrence a young army lieutenant in the Arab Bureau intelligence unit. He backtalks his superiors, and comes off as pretentious and arrogant. He paints, knows his classics, and deports himself with a certain effeteness. The film can’t explicitly depict him as gay, but the subtext is a brick to the face.

But when he’s dispatched to Arabia (to shadow Prince Faisal, a putative ally of the British in the revolt against the Turks), his alienness becomes an asset. He establishes a rapport with the tribes, and comes up with daring, impossible plans: crossing a desert that can’t be crossed, storming a city that can’t be taken. He stands out – both with his white complexion, and inability to play the game the normal way – and is soon at the center of regional politics.

His handsome face becomes a generic slate onto which various characters project their desires – Prince Faisal’s wish for Arabic independence, Sherif Ali’s personal ambition, Auda Abu Tayi’s lust for plunder, General Edmund Allenby’s desire to entrench Britain’s tactical position against the Ottomans. Like all messiahs, Lawrence is who you need him to be, and like all messiahs, he is disposable.

Virtually no part of this movie could be made now. There are no speaking roles for women. The set of Aqaba was built by Franco’s fascist regime. The idea of British intelligence running the show in Arabia is portrayed as morally neutral or positive. Most of the actors (Omar Sharif excepted) are not Arabic but British or Americans in brownface. Anthony Quinn, who plays Auda Abu Tayi, has a Brooklyn accent and a silly fake nose.

I’m sure most kids now watch this movie for a school report, and write about how it’s a racist old film about how unenlightened Arabs just need a smart British person to whip them into line.

But the point of Lawrence’s character is that he isn’t British, except in a nominal sense. He has no loyalty to his homeland. When he’s praised for his achievements by Allenby and Dryden, their words sound hollow and false. Lawrence never conquers Aqaba out of some “Rule, Britannia!” patriotic impulse. It’s something darker, less explicable, less controllable. In any case, the sympathies he develops for the Arabs soon cause Allenby to suspect he’s gone native.

But what does Lawrence really want? I kept asking this of the film, but director David Lean leaves it unclear. Lawrence is a confusing person: outwardly flashy and flamboyant, but inwardly hollow. He’s more defined by what he doesn’t have than by what he does.

We see a streak of kindness in Lawrence (as well as an unwillingness to get his hands dirty), but also a vanity that almost gets him killed. While spying undercover in an enemy city, he is captured and mocked by a Turkish bey. A real politician would not have risen to the bait, but Lawrence lashes out, and earns himself a beating. Soon it becomes clear that the British will betray the deal they brokered with Faisal, shattering the last of Lawrence’s confidence in himself.

His stated motives for his actions (“I just want my ration of common humanity!”) sound curiously unspecific. It shows the danger of not having a moral center: you get sculpted and distorted by whatever your environment is. He ends up as an existential ghost, haunting the desert like a Dybbuk, detached from the world he thinks he controls. Lawrence reshapes the politics of the Middle East to suit himself, but he’s reshaped by it in turn. Soon this nightmare becomes apparent in his eyes. He’s nothing, and knows it.

Lawrence: I killed two people, I mean two Arabs. One was a boy. That was yesterday. I led him into a quicksand. The other was a man. That was before Aqaba anyway. I had to execute him with my pistol. There was something about it I didn’t like.

Allenby: Well, naturally.

Lawrence: No, something else.

Allenby: I see. Well that’s all right. Let it be a warning.

Lawrence: No, something else.

Allenby: What then?

Lawrence: I enjoyed it.

Is this an accurate depiction of Lawrence? I’m doubtful. It occurs to me that most “weirdos” are not actually that weird – they’re non-freakish people who can play the role of oddball on command but are actually fairly normal. David Bowie (who likely took fashion notes from Peter O’Toole in this movie) is a good example.

Imagine if Forbes Magazine ran a “most inspiring poor person” contest – most of the entrants would be crustfunders or fakers or LARPers. Genuine poor people don’t read Forbes Magazine and would never hear about the contest. It takes lots of social cleverness to become famous: a misfit celebrity is something of a contradiction in terms. Genuine freaks are either ignored, or are put in cages to be gawked at. Freakishness is as prone to gentrification as anything.

But even if Lawrence wasn’t like this, the depiction still rings true in a game theory sense. Sometimes it does pay to be an alien dropped out of the sky. Lawrence has no reason to prefer one tribe of Arab over another. He is blind to doctrinal differences, doesn’t care about interpretations of Wahhabism vs Hanafalism. This is his strength. It’s often worse to be a little different than vastly different (other players “neargroup vs fargroup”). Think of how Genghis Khan is popularly regarded in society, vs Hitler. Or how the Tlaxcalans of Mexico allied with the fargroup Spanish agains the neargroup Aztecs.

Lawrence is Genghis Khan to the Arabs. In his first few days in Arabia, he learns a harsh lesson. Upon landing in Arabia, he journeys with a Bedouin guide. The guide drinks from a well owned by Sherif Ali without permission, and is killed by Ali. Lawrence drank too, but is spared. In this land, being a foreigner is like protective armor. He doesn’t yet know about the Islamic principle of amān (safeguard) which likely just saved his life.

Again, Lawrence of Arabia is better off watched as a fantasy film, not as commentary on the geopolitical ramifications of the Sykes-Picot treaty or whatever. Beethoven once said “To play a wrong note is insignificant; to play without passion is inexcusable.” Real life contains a lot of smallness and silliness and incidence that cannot be used as fodder for a story. Epics, almost by definition, have many wrong notes.

The depictions of Arabs as squabbling idiots who can’t even keep the power on without British help (that’s literally a scene at the end) may come off as racist. But it may have a grain of truth. Certainly, Saudi Arabia was late to the modernisation game. Here’s an interesting anecdote I read on Matt Lakeman’s blog (for which he tragically does not provide a source)

Wahhabis oppose innovation. This is not just an accusation flung from the moral high horse of my modern liberalism, this is how Wahhabis describe themselves. They believe in a strict literalist reading of Islamic texts, hence innovation is deviation from the texts. This mindset expands beyond esoteric theological theory into everyday life. The founder of modern Saudi Arabia, King Abdulaziz al Saud, publicly smashed a telegraph to appease his clerics who worried he was using too much modern technology.

That aside, some scenes do overplay their hand, and come off as goofy. The action was as good as it got in 61, but it’s not as visceral and bloody. It’s very “stagey” – punches that clearly miss, men who don’t duck when fired upon, but stand up, so the cheap seats can see them. There’s the obligatory scene where a man gets sucked to his doom by quicksand: it’s supposed to be shocking and horrible, but the fact that it’s quicksand gives it a Roger Corman quality.

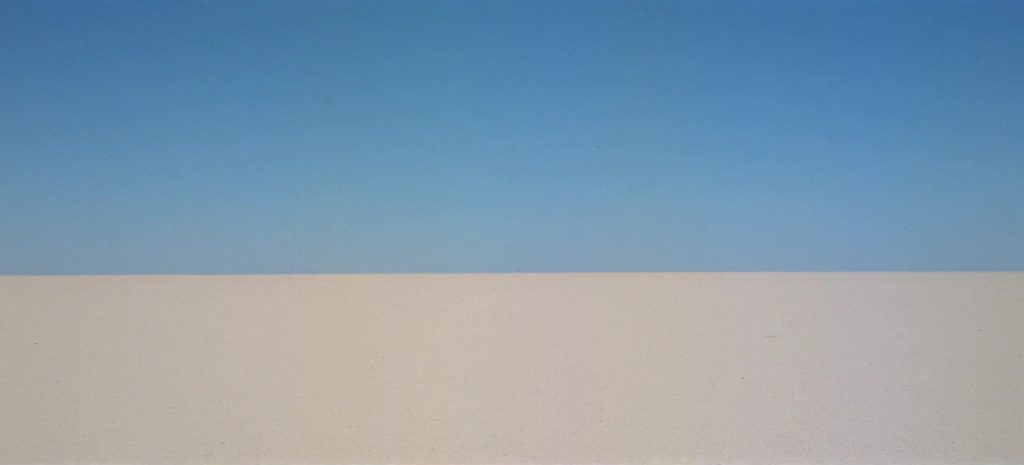

We’re meant to watch it on a huge screen (and on 70mm stock) and some scenes don’t really work on a small one. As Lawrence’s men cross the terrible Al-Nafud Desert, the warrior Gasim falls from his camel, and is left behind. When Lawrence discovers this, he goes back to rescue him. It’s an important scene, setting off an IOU that pays off later in the movie…but if you watch it on an 640×480 DVD rip acquired in an extremely legal fashion some shots (such as a distant man walking across the dunes, like a crack piercing the sky) become impossible to understand. The human figures are too small to see. Can you see the man in the picture below? Look closer.

The film has some of the best desert footage ever shot. Lean has a sense of depth and space, and how to make it resound off the screen like an echoing scream. This movie made me feel gravity. At times, I felt vertigo swirling out, as if I might fall forward into the celluloid.

It diminishes the human side of the conflict. Imposes a sense that none of it truly matters much. Whoever prevails in the Arab Revolt, the only winner will be the desert.

Everyone seems tiny in this ocean of sand. The British, the Hashemites, the Bedouins, the Ottomans – are just ants floating in an ocean of sand, slowly dying in a light more blinding than any darkness, hunched double with their thawbs and keffiyehs flapping against blasting wind, hoping that the oasis in front of them actually exists. They might be princelings, warriors, or statesmen, but the desert equalizes them, crushing them all down to nothing. The film achieves an odd effect: the mythic figures look so powerless that they actually become human again.

The film brilliantly portrays the main character’s psychological collapse. Reportedly, Lean’s cameras kept malfunctioning, because they were choked up with sand. Lawrence eventually reaches the same point. He is humiliated, damages, and begins descending into the kind of honor-feud vindictiveness. He learns of the British plot to betray Arab interests, and begins to wonder what it was all ultimately for. A sense of setting sun hangs over everything: the end of history. It’s one of Hollywood’s final great epics.

According to Hollywood lore, the cheapest special effects are bare breasts and dwarves. Lawrence of Arabia has none, but it finds another one: deserts. But the desert’s so big and empty that it projects futility. What can one man ultimately do out here, except lose?

The final time Lawrence meets Auda Abu Tayi, he says “I pray that I may never see the desert again.” To which Abu Tayi says “there is only the desert for you.”

The final shot argues that this is true. He is driving out of Arabia. “‘home, sah!” his driver says. But we see dry dust twisting up into the air behind the car, and it tells another story. The hot, soul-chilling desert is coming out with him, like a shadow that will never leave. He can’t run from who he isn’t. Wherever Lawrence goes, he will find the lone and level sands waiting for him.