I saw this film for Christmas, the most wonderful time of the year.

One advantage of me being Australian (aside from the whole walking upside down thing, which gets old fast) is that I have an outsider’s view on American entertainment. For example, I don’t know who Kirk Cameron is. A sitcom actor, or something. When Saving Christmas came out and was hammered by critics, many reviews took the line of “haw haw! It’s Mike Seaver from Growing Pains!” I didn’t care about that stuff. I judged the film on its own demerits.

It’s terrible. Silver linings, though: we’re still celebrating Christmas in 2022, which means Kirk’s crusade to save the holiday was a success. I wonder how he did it?

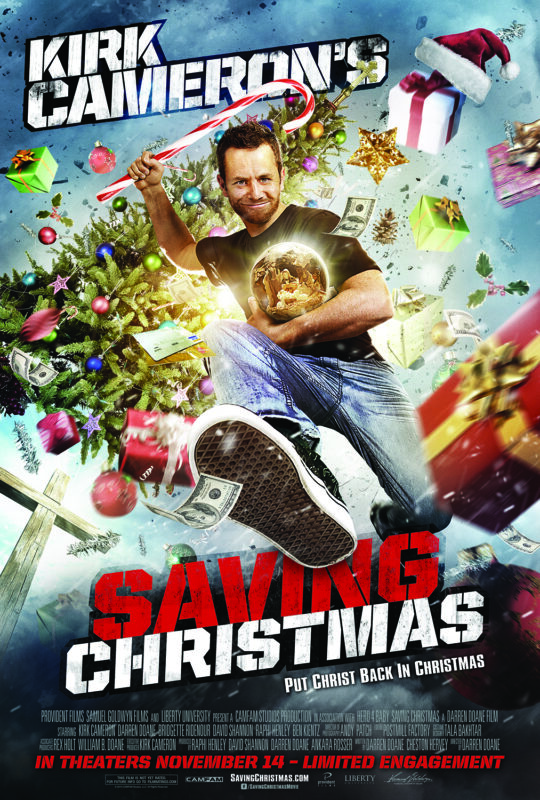

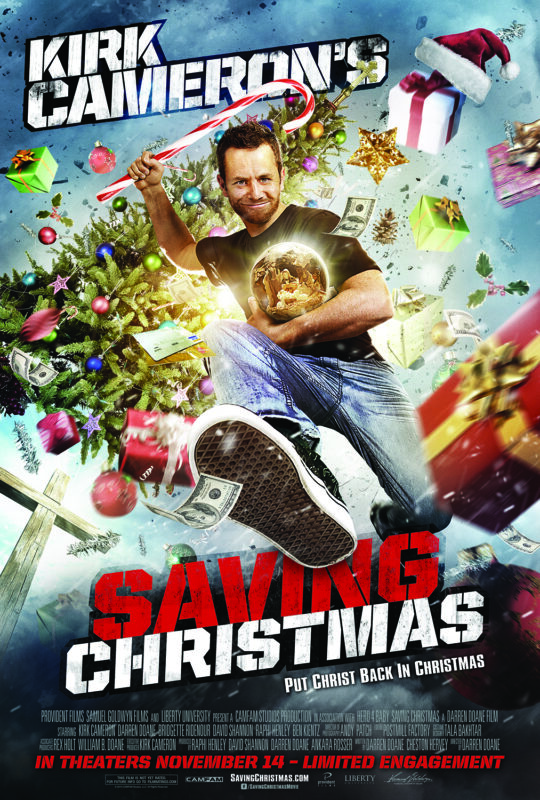

Don’t be fooled by the action-packed cover: Saving Christmas is a vlog of Kirk Cameron sitting in front of a camera, gesturing with his simian hands, his ghastly chimp-like visage twisting with rancid condescension as he explains the meaning of Christmas to all of us dumb idiots. I have never felt so patronized by a stupid person. He has the energy of an uncle explaining that airplanes fly by flapping their wings.

He knows how to save a buck, I’ll give him that. The movie has two sets: “some dude’s house”, and “some dude’s car”. Occasionally he spices things up with “B-footage” that looks like it came from a stock footage site. This film cost literally dozens of dollars to make, and I hope it earned back every penny.

Is this even a movie? In 2017 it barely passed muster. In 2022 it more resembles a high-effort Youtube video by someone called “The Libtard Crusher” whose avatar is Trump throwing Fauci out of a helicopter. All it lacks is a crudely animated furry character who looks smug when he makes a point…well, it has Kirk Cameron, now that I think of it.

So what dubious message does Craptain Kirk have for us?

It’s not “Christmas is overcommercialized!” Kirk is all for commercialization. “Don’t buy into the complaint about materialism during Christmas. Sure, don’t max out your credit cards or use presents to buy friends, but remember, this is a celebration of the eternal God taking on a MATERIAL body. So, it’s right that our holiday is marked with material things.”

He argues – unconvincingly – that “secular” traditions (Christmas trees, nutcrackers, Santa Claus) are Biblically-based. Nutcrackers? They’re soldiers, and Herod had soldiers. Christmas trees? Jesus was crucified on a cross made of wood, which comes from trees. Baubles? They represent the fruit in the Garden of Eden. And so forth.

It’s a simple formula. Is $THING part of Christmas? Just Ctrl-F search for $THING in the Bible, and there you go. Anything you like can be a Biblically-approved Christmas tradition. “Like a computer wrote it” is a common criticism lobbed at movies that are formulaic or uninspired. Saving Christmas goes further: it’s the world’s first movie that could have been written by a one-line Bash script.

Winter? Well, God created the winter solstice. When he’s in a pinch, Cameron falls back to the “God made it” argument, which kind of makes the rest of the film unnecessary, because then everything is part of Christmas.

And this distresses me, because my family had a disgusting proctopaedophiliac Christmas tradition called “oobleklaart”. It’s a heinous sex act, banned in 31 countries and counting, involving a monkey, an unripe rambutan, a power drill, and…ugh…just thinking about it makes me shudder. Those poor gerbils…

Anyway, if Kirk is correct, oobleklaart is authentically part of Christmas, because the 27 separate items and ingredients necessary to perform it (we’ll ignore the plutonium-239, which is man-made) all come from God. Is this true? Is oobleklaart Christmas? Say it isn’t so, Kirk.

In general, I’m not on board with attempts to make Christianity hip and happening.

Firstly, none of these people would recognize “hip” if theirs was smashed by a sledgehammer. At the end there’s a rapped version of “Angels We Have Heard On High”, which is a risky move for a group of actors who have never heard a rap CD that didn’t have “CLEAN VERSION” on it. When they dance, they flail like electrified corpses.

Christianity should transcend cool. The Bible has a certain dignity to it. It’s not a trite or silly book. Trying to tie it up with a bunch of toys doesn’t even reach the level of sacrilige. It speaks to a cultish obsession with dopamine that’s as secular as it gets. “Don’t ask questions! Just consume product and then get excited for next product!” Christmas may survive commercialism. It may not survive Kirk Cameron.

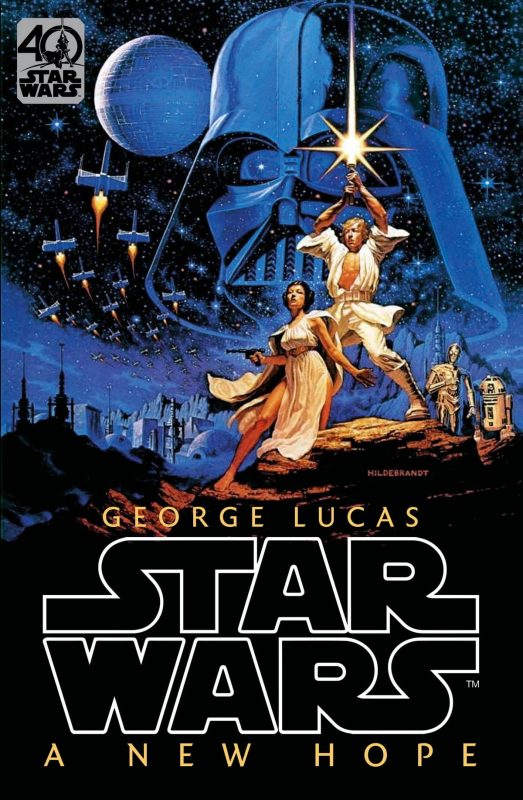

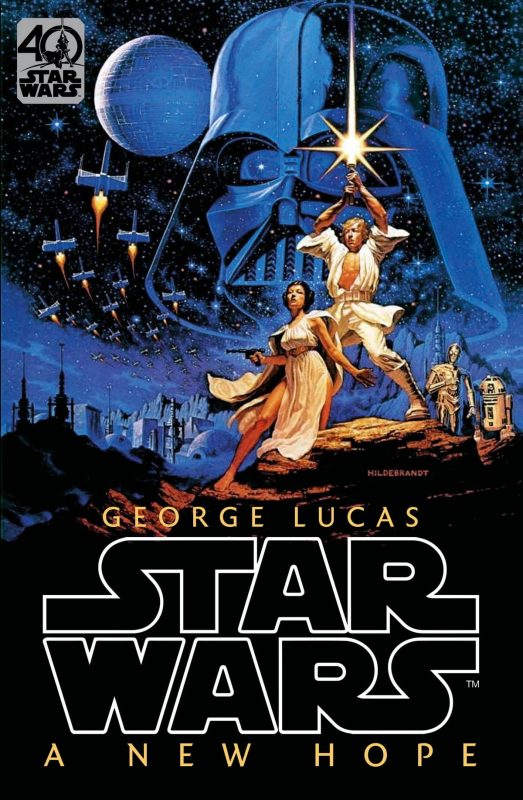

Circumstances sometimes force us to dislike movies. I remember being in a Blockbuster video with a friend (not long after seeing The Phantom Menace) when he learned that I hadn’t watched the original movies. We then had a Never Seen Star Wars conversation. “Whaaaaaaat? Dude! How have you never seen Star Wars?”

I still don’t know what response is expected in this situation. Does it take effort to not watch a film? Was I supposed to reveal my secret never-seen-Star-Wars diet and workout regimen? Regardless, he snatched tapes out of my hands and reshelved them. My heart sank: I knew we’d be watching Star Wars that night.

Quite unfairly, this ruined the film and franchise for me. To this day, my principle association with Star Wars remains “the kind of thing people bully you into enjoying.”

I admire parts of it now; it has good puppetry and special effects, and Alec Guinness is a talented actor. His scenes on the desert planet (which were filmed in Tunisia, I think) have the stately gravitas of Lawrence of Arabia or The Man Who Would Be King. Long shots of desolate horizons, with grime and rust and sand corroding through the frame. There’s a sad, understated quality to his performance – the sun’s going down, his sun’s going down, and a once-glorious empire is rotting like late summer fruit. It’s a strikingly British film in places.

In other words, I enjoy the parts where Star Wars isn’t Star Wars. The rest of the movie is a colorful ball pit of frenzied kiddie nonsense – lightsabers, blasters, the Force, the Millennium Falcon – that doesn’t move me at all. The more platonically Star Wars the film gets, the less I can stomach it.

It’s obvious that Star Wars’ tacky, toyetic style dispersed through culture like poison spores and made the world worse. Less obvious is the fact that it didn’t even really work in the original film. Dark Vader and the stormtroopers resemble shiny plastic action figures: any sense of menace is undercut by how stupid they look. One of the more over-the-target gags in Mel Brooks’ Spaceballs is that the villains of Star Wars are impossible to take seriously.

When Luke leaves the desert, the film’s look becomes “plastic and PVC”. Next to the awesome heft of 2001: A Space Odyssey, Star Wars is a weightless thing. The X-Wings resemble model kits glued with Araldyte, and they’re flown by pilots wearing dorky oversized NASCAR helmets equipped with welding goggles. Is there a point to all this safety gear when you’re flying at sixteen times the speed of sound? One brush with anything and you’re toothpaste.

The actors are either deep-sixed by the script or just generally suck before the writing even gets there. Mark Hamill has the charisma of a crash test dummy. Carrie Fisher is a sociopath who wisecracks about Chewbacca being excessively hairy on the same day her planet blows up and all her family and friends die. And honestly, why are we still pretending that Harrison Ford is a charming rogue? He’s a sour, snarky grinch whose main trait is that he doesn’t want to be in the movie.

There is a gay robot. I’m not offended by the gay robot. Gay robots are a time-honored British archetype. He’s just a very odd character given the “Epic Campbellian space opera that should be taught in schools and forcibly inflicted upon children in a collective hazing ritual” role Star Wars has in our culture.

The Star Wars setting is interesting, if incongruent. It’s a universe where moon-sized battlestations exist and lasers shred entire worlds to plasma…but spaceships can still be fixed by smearing engine oil on your arms and rummaging with fuel lines. Lucas’s futuristic setting only looks backwards (particularly, to the movies he saw in his youth). He provides pastiches of WW2-style dogfighting, “greaser” muscle car movies, wild west gunfighter duels, Turkish prisons, and medieval swordfights. Speaking of, lightsabers seem like they’d be dogshit weapons. Who needs a sword that annihilates everything it touches? A careless backswing would split your head in half. The careful, slow-paced lightsaber duel at the end is actually realistic: that’s the only way you could ever fight with those things.

Lazy reviewers who don’t think usually default to describing films as “a love letter to [the film’s most prominent influence].” Lucas wrote a love letter complete with spelling errors, backward letter Rs, and semen stains. He sometimes comes up with inspired ideas, and sometimes he squeezes the ball through the hoop in spite of himself, but nowhere do we see evidence that he’s competent. Star Wars is just an occasionally compelling mess, roughed into shape by skilled and patient editors.

Was the opening text scroll his idea? It’s a good example of my least favorite thing: audience handholding. Yeah, why reveal the backstory through context or dialog, when you can just put some text-based exposition on the screen. Why even make the movie at all? Just throw the entire screenplay up there in yellow News Gothic Bold text. Really good filmmaking there.

I am not reacting to Star Wars so much as it’s fans and its place in society.

Star Wars belongs with bacon, duct tape, I Fucking Love Science, We Don’t Deserve Dogs, and Beatles worship. In general, I am creeped out by effusive public cheerleading for things that are universally loved. Why? It’s not wrong, exactly, to enjoy a thing that eight hundred million other people enjoy, but it’s strange to turn that into a marker of your identity. What hole are you trying to fill with your Han Shot First T-shirt?

I have a grudging respect for people who join cults. At least QAnon folks are brave, and willing to go against the tide. Where’s the bravery in being a fan of a thing like Star Wars? You are the tide. I don’t hate you if you publically adore this film, but I think you don’t really like it: you just like supporting the winning team, and that in the world of the movie you’d be working for the Empire.

Also, a flickering holographic ghost is not more powerful than I can possibly imagine.

A 1942 film where Donald Duck supports G*m*r*g*te and votes for Tr*mp.

Context: from 1942 to 1944, Disney became a propaganda outlet for the US Department of Defense, producing over 400,000 feet of film for the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Treasury. This allowed the studio to remain financially solvent under difficult wartime conditions. Most of these films are disposable hackwork, although 1943’s Education for Death (dir. Clyde Geronimi) is strikingly dark and existential. But it was Der Fuehrer’s Face that gained a second life on the internet thanks to its fever-dream “how does this exist?” quality. The first time I saw Donald do a Nazi salute, a blood vessel exploded in my brain.

It’s among the odder relics in the Disney canon. Never actually banned, Der Fuehrer’s Face kept getting missed in home video releases, thus making it the closest Disney came to a “Censored Eleven” short. Once the war ended (and the world’s focus shifted from “fighting Nazis” to “imagining Nazis”) it increasingly seemed a bizarre artifact, adrift in time. This made it perfectly suited for the irony-poisoned internet. If you made a list of Nazi kitsch – Ilsa the She-Wolf, Wolfenstein 3D, and so on – it’s fair to say that Der Fuehrer’s Face would be the only Disney short to make the list.

Here’s what I learned from Der Fuehrer’s Face:

- Adolf Hitler canonically exists in the Kingdom Hearts universe

- Donald occasionally wears pants

- Scorcese’s Casino once held the record for most uses of the word “fuck” in a feature film (422, supposedly). Der Fuehrer’s Face probably holds a similar record for “heil Hitler” (37, by my count).

- This does the “where the fuck is your chin?” joke fifty years before Garth Ennis’s Preacher. Hermann Göring is bragging about how they’re “Aryan pure supermen” (or something) and we get a shot-by-shot of the Axis high command so we can see how fat, skinny, bald, effeminate, and Asian they are.

- The 1940s exists across an unbridgeable cultural gap. A lyric goes “If one little shell should blow him right to…” with the “…hell” censored by Donald banging his head on a shell. BONK!

- The trippy sequence involving flying/marching bombshells was adapted from Dumbo, making it possibly the oldest example of Disney recycling animation.

- “Character dying of starvation” is my favorite cartoon gag. Dipping a single coffee bean in a mug of water, eating bacon and egg scented air for breakfast…that kind of thing is never not funny. The wooden “bread” is a reference to the wartime practice of stretching out flour rations with sawdust.

- The direction of the swastikas (on drumskins, armbands, and posters) keeps changing. Can you spot all the times this happens? Turn it into a game, in case you’re bored and videogames are suddenly uninvented.

- Donald does a good job assembling shells overall. He deserved that paid vacation.

- The movie accidentally includes some caustic anti-American satire. Donald wakes from his nightmare to see a terrible shadow on his bedroom wall: a looming figure with an arm raised above their head. He begins to Sig Heil…and then sees it’s the Statue of Liberty. Likewise, the message of the film seems to be that Americans had better really put their shoulder into the war effort, because if Hitler wins we’ll slave all day building shells.

- Disney, by all accounts, wanted to make escapist fairytales. But fairytales have a way of backpropagating into mainstream culture. “Who’s afraid of the big bad wolf?” became a national rallying cry during the Depression. “There are no strings on me” appeared on the signs of striking animators outside Disney’s Burbank office in 1941. The “comix” movement of the 70s was reacting against the Disney Corporation’s conservatism, but that same conservatism was the fuel they relied on.

- A standard propaganda trope (seen here) is that The Enemy is both all-powerful but foolish and easily defeated. Germany (fictionalized as “Nutziland”) is portrayed as both ludicrous and scary: Big Brother with an extra chromosome.

- There’s a campy gay panic moment where Göring makes effeminate gestures while talking about men. It’s vague and deniable but definitely there.

- At least two of the dictators mocked in the short were huge Disney fans. Dr. Joseph Goebbels, in his diary entry of December 22, 1937, writes of his Christmas gift to Hitler:“…18 Mickey Mouse films. He is very excited about this. He is completely happy about this treasure.” Hirohito, too, was in the House of Mouse – he visited Disneyland in the 70s and was even buried with a Mickey Mouse watch.

- The song’s a fucking banger