There’s not much I can add to the The Thief and the Cobbler’s legend except to say “yes, it’s that movie.”

It’s the troubled masterpiece of Canadian-British animator Richard Williams (Who Framed Roger Rabbit, etc). He was an obsessive perfectionist/auteur in an industry with little tolerance for either of those things. It’s said that The Thief and the Cobbler took thirty years to make, but that’s not quite true. The film was never finished. The Thief and the Cobbler took thirty years to not make.

This adds to the film’s aura: strictly speaking, it doesn’t exist. But its legacy mainly rests on the fact that it has possibly the best 2D animation ever seen in a feature-length workprint.

It’s 90 minutes of an animator making cel sheets his bitch. The film is beyond technically impressive and approaches “insane”. Richard Williams storyboards things you’re never supposed to do in 2D animation and then does them twice, backward, wearing Persian slippers. Revolving POV shots. Crowd scenes. Textured fabric. You name it, this movie has it. The only computers involved were the ones that processed the bankruptcy and liquidation of his studio.

Any animation nerd can quote favorite moments by heart. Tack tumbling out of his workshop, with dozens of individually animated tacks spilling from his pockets into Zigzag’s path. The Thief crawling through the palace sewer system, with pipes bulging out comically. Zigzag climbing a spiral staircase. Tack fighting the Thief for Yum-Yum’s shoe inside the MC Escherian palace. The Thief getting thrashed by polo players, with the ball implausibly following him around like a target-seeking missile. The dolly shot of One-Eye’s camp, zooming out from the middle of his iris.

And of course, the destruction of One Eye’s massive war machine, which is so excessive and overstimulating that you’ll snort coke just to calm down. It’s not just animation for animation’s sake, either. The film has a lot of style, and evokes the mythical Orient far more effectively than, say, Aladdin (which comes off as American teenagers at a Vegas hotel by comparison). The Thief and the Cobbler looks the way a Persian carpet would if the stitches could move.

Margaret French’s story (a simple fairytale) isn’t that interesting when stripped of its visuals. It’s a good example of how technique itself can be art: instead of animation being used to tell a story, a story is used as a scaffold for animation itself. Which is fine, although it requires a shift of thinking for people used to stories being paramount.

The characters are stock archetypes: Tack is a silent film hero, the Thief is a silent film villain, Nod is a sleepy king, One-Eye is a barbarian invader. Zigzag (with a cel-sheet chewing performance by Vincent Price) is a hilarious camp villain. The characters’ behaviors are as simple as their movement is intricate: this is a movie simple enough for the smallest child to understand.

The tale of the movie’s production is long, harrowing, and (ultimately) tragic. After decades of tinkering on the film (with a few injections of cash from such parties as the House of Saud), Williams finally received full financing in the late 80s. This lifeline became a noose. When he failed to deliver the film on time, the project was taken away from him, and auctioned off in a lowest-bidder situation to whoever would get it done cheaply.

That someone was Fred Calvert, who “finished” the film in 1993. I don’t mean he completed The Thief and the Cobbler. I mean he slapped together a film-shaped object for as little money as possible, which incidentally contains some of Williams’ animation.

Calvert is defined by The Thief and the Cobbler‘s destruction the way Richard Williams is defined by its creation. Fans universally regard him as having ruined the movie. He’s the ultimate bad Hollywood stereotype: the studio hatchet man. The movie’s final gag (which involves the thief ripping the film from the reel and stuffing it into his pocket) seems eerily prophetic.

Yes, it’s hard to excuse what Calvert did. His new scenes look as shoddy and cheap as a Saturday morning cartoon: they stick out like twine and tissue paper holding together fine damask curtains. Calvert didn’t “edit” Williams’ footage so much as randomly guillotine it into shape. Important parts of the story are now gone: we don’t see Zigzag attempting to feed Tack to Phido, which lessens the poetic justice of Zigzag’s death. The brigands have nothing to do in Calvert’s version, while in Williams’ workprint we see at least see them fighting in the final battle. Scenes of soldiers dying were shortened or cut (for violence?), which leaves us wondering where One-Eye’s army went.

Calvert added four songs, because animated musicals were big that year. We shall not speak of these songs, because they make getting crapped on by an elephant seem like a joy.

In September 1993, the film saw limited release in South Africa (why?) and Australia (why?). It was released again in August 1995 after a further round of destructive edits and general stupidity. (Fun fact: the green women were cut because they could be interpreted as One-Eye’s sex slaves…an edit personally requested by Harvey Weinstein!).

Neither release made money. The total production budget was in excess of $25 million, and although the movie’s box office profits are unclear due to the film’s complicated release history, they couldn’t have reached a million dollars. Shovel twenty five million dollars down a garbage disposal unit, and then sell a small piece of beachfront real estate in Florida. Congrats: you’re financially ahead of the Thief and the Cobbler.

Calvert minimized his role in the disaster, saying he never had creative control over The Thief and the Cobbler, and that most of the bad decisions (such as the songs) were forced on him by higher-ups. True or false? Who knows? Victory has a hundred fathers and defeat is an orphan.

But Calvert can be defended a little, too. At least he can say he delivered a finished film. Mangled and butchered though it was, his movie exists. Richard Williams couldn’t finish his after thirty years and God knows how many millions of pounds. Look at the work print: it still wasn’t close to being done. The princess was still half-animated. Critical scenes did not exist.

Calvert made some defensible decisions. He tightened up the story. The main villain (One-Eye) is established right at the start, instead of coming out of nowhere in the second act, and he has a better voice and a better death (his concubines throw him into the burning wreck of the machine, instead of sitting on him). The Thief’s characterization is more defined: he now has a fetish for golden things specifically, instead of just stealing everything he can. Detours (such as the maid from Mombasa) are cut, and the movie is better for it.

Blame should go to Williams as well as Calvert. The perfectionism that made The Thief and the Cobbler great also dug its grave: why did he waste so much time animating superfluous scenes of the Thief? They’re fun, but they’re not the movie. There’s enough effort on the screen to make three animated films, it just wasn’t used efficiently. He was his own worst enemy. There’s a saying in Hollywood that if the audience leaves praising the set design, the film is a bomb. The Thief and the Cobbler’s workprint is all set design.

Transhumanists speak about “paperclip maximizing”, conveying the idea that a superintelligent AI need not be malicious to screw us over. It might merely want to build as many paperclips as possible, until they cover the planet. No matter how benign or innocuous your goal (“make paperclips!”), it will destructive in the hands of a machine, because it can’t understand the big picture.

Williams was a human paperclip maximizer. He seems to have been guided by an imperative to make pretty animation, so he made more of it, and more of it, and more of it, and never knew when to stop. This would be fine, if he was spending his own money. But once outside financing gets involved, there’s only so long you’ll be allowed to chase a dream. If you owe a bank five dollars, that’s your problem. If you owe a bank five million, that’s their problem. Money always comes with strings attached, and when the sums are large, the strings become golden handcuffs.

The Thief and the Cobbler is a story of glory and grandeur, of madness and excess, of ruin and shadow and devouring flame. It’s also a film about a cobbler.

Some art forms are like staring across a large and flat field. Sunday morning comics (do they still exist?) are all the exact same quality. There are no good ones or bad ones. Garfield could be the best of its kind or the worst. There’s no way to tell. Their bell curve is a bell line: a single vertical stroke that is both infinitesimally thin and high enough to leap into the stratosphere.

2D animation is different: its a plain ridged by great peaks and crevassed by huge gulfs. When it’s bad it’s incredibly bad: the worst thing ever conceived of by the human mind is probably animated. But for me, great animation exists on a level that basically nothing that’s not an animation can touch.

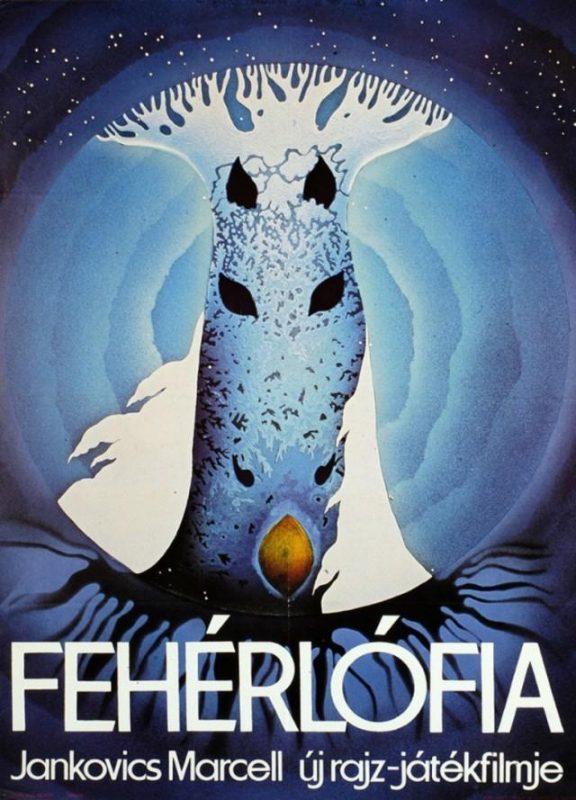

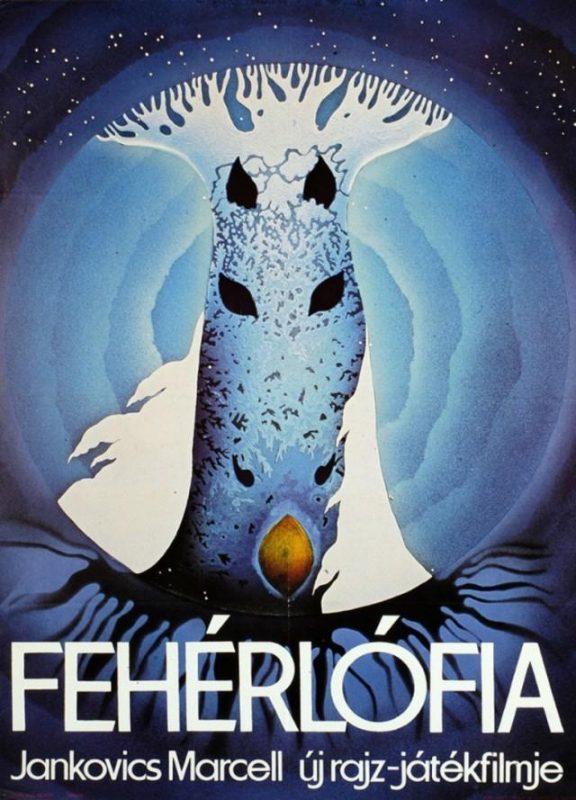

Son of the White Mare, or Fehérlófia, is a 1981 Hungarian animated film that I watched on Peter Chung’s recommendation. I was curious as to what I’d get out of it, considering I know only one Hungarian word, “Tökfej” (lit. “squash-head” but with idiomatic sense between “idiot” and “asshole”), and only because a heavy metal band recorded a song with that title.

It’s like a Disney film, in that it adapts a folk story (in this case, an “ancient Hunnic and Avaric legend” of the three brothers, Fanyüvő, Kőmorzsoló, Vasgyúró, who fought a war against an army of dragons). But where Disney films are reverent as a dull church service, Fehérlófia is energetic and lively. And where Disney films try for styleless realism, Fehérlófia wants to be like nothing you’ve ever seen before.

A realistic myth is a contradiction in terms, and it wastes no time in trying to be “faithful”. Instead, it’s a surrealist vapor that seems made to be inhaled rather than watched. This is one of those midnight movies viewed by college kids who snicker “what drugs were they on?” Probably none. Something can invoke a psychedelic state without being authored in a psychedelic state – it’s probably easier if it isn’t. LSD is formulated by trained chemists, and pressed into pills by machines.

Imagery grows on Fehérlófia’s cel plates like mushrooms on a fallen log. Colors mean things, shapes mean things. It’s a masterclass on how to talk with paint instead of words. I found the voice-acting to be annoying and anti-climactic, and if not for the music (which was nice) I probably would have viewed the film on mute.

There’s a lot of “shape language”, and things get pretty symbolic, with the heroes having rounded, organic shapes and the monsters having an industrial, Soviet brutalist aesthetic. I don’t think Fanyüvő ever calls a dragon a tökfej, but he should have: they’re real pieces of work.

There’s also a psychosexual undercurrent you wouldn’t get from Disney – somehow, Fanyüvő’s sword always ends up hanging between his legs.

It’s technically creative, too. Fehérlófia does not have a single line. Color is allowed to clash directly upon color, without dark penstrokes getting in the way. This gives it a fluidic feel, like watching a lava lamp bubble. And though it might seem the opposite of the “ligne claire“ style of Tintin, it achieves the same effect: combining everything on the frame into the one level. Most animation has a clear distinction between foreground action and background plate. Here, it’s basically all action.

(I’m interested in how exactly the key animator worked. Were lines drawn as a reference and then discarded? Were cels painted freehand?)

It’s a testament to visual storytelling that my illiteracy didn’t seem to matter, because I was fascinated by Fanyüvő’s quest, and the way it was depicted in abstract incinerations of light and color.

The film was created by Marcell Jankovics worked under the auspices of Pannonia Film Studio, one of Hungary’s few native animation studios (One of Pannonia’s alumni includes Gábor Csupó, who co-founded the animation studio known for Rugrats et cetera). He made several films, which have a certain niche appeal. His most famous mainstream moment was probably the film that ended up becoming The Emperor’s New Groove. What’s the the Hungarian version of “Alan Smithee”?

According to IMDB, production was difficult.

According to the director, the animation crew had to work under horrible conditions. Their work building was a rickety wooden construction added to the main studio building. Concept art and other production papers were carelessly littered across the floor and trampled over, as the studio saw no point in preserving them. The celluloid sheets were scratchy and of low quality, and the paint had a tendency to form clumps and crumble off the cels after drying. At one point, 600 completed animation cels had to be thrown out and hastily redone because they were unusable. The animators eventually decided to start manufacturing their own paint, and Jankovics himself helped out with painting the cels. He recalls that the work was so stressful, one of the artists broke out in tears. To buy more production equipment that Pannonia Studio couldn’t afford, the people working on the film even had to take up additional jobs elsewhere.

Movies like this don’t make money. Animation in general was in a slump in the 80s – even Disney was in a precarious situation – and animation for adults has always been a rough sell. The fact that Fehérlófia was made against adverse winds adds to its scrappy charm.

Some things entertain, illuminate, inspire. But some do something more: make a case that their medium is worthy of existence. Fehérlófia is one of the heights of animation. It’s a brilliant, elegant lawyer’s brief for the entire animation genre, showing what’s great about it, and why it’s important.

It’s an cruel lottery, becoming famous for being bad. For every Tara Gilesby there’s a twenty year old woman scrubbing the internet of her thirteen year old self’s Dramione mpreg femslash drabblefic, praying none of its readers made a copy. For every Cats there’s a very real tortoiseshell positioning its anus uncomfortably close to my face as I type this. And for every Neil Breen there’s a Charles E Cullen, who directs loosely-described “movies” that inflict accurately-described “brain bleeds”.

Killer Klowns from Kansas on Krack is about two unemployed clowns who get hooked on crack, kill people, and live in Kansas. You have to go into this movie with the right expectations. Does it have the biggest budget or the best actors? No. But is it a blast of campy B-movie fun, made with enthusiasm, passion, and heart? Also no.

Everything about it is wrong, even the title. Killer Klowns on Krack would have been dumb but punchy; adding from Kansas makes it too wordy and ruins the pun. There’s no organization called the KKKK. Cullen apparently believes that titles are funnier with four Ks than three Ks.

KKfKoK is filmed on a consumer-grade hand-held camera by a person who’s clearly drunk, although no drunker than you’d have to be to watch it. It’s very much a shoot-using-whatever’s-lying-around kind of film, with production values six levels below “indie movie”, and one level above “two kids making a movie in an afternoon”. It looks incredibly cheap. Kudos to the coin from behind a sofa cushion for financing the film, the year 1994 for providing the video editing software, and Cullen’s film school degree for not existing.

Honestly, he’s kinda brilliant, and I think big studios could learn some tricks from him. Why construct a “set”, when you have a perfectly good “trailer park”, just ready to use? Why waste time on a “second take” when you have a perfectly good “first take”? Why hire “actors” when you have a perfectly good “people who aren’t actors”? Why be “sober” when you have a perfectly good “drunk”?

It’s never clear what parts of Killer Klowns are supposed to be bad. When the camera skews queasily, is this a Dutch Angle, or did the director’s hand slip? When the footage cuts to black and white for no reason, is this the director’s attempt at mood, or did he accidentally punch the B&W button on his camcorder?

Cullen has talents aside from directing. For example, he’s also a puppeteer. I guess? I’m not sure I want to understand what this thing is, but I believe it’s a puppet.

But wait, there’s less! Cullen’s also a musician. His metier is soulfully-sung country, as shown in the song “Fading Into The Light”. “Corndogs for breakfast / Tuna for supper / Boredom at sundown / Pepsi with uppers.” I hope you enjoy this song, because it drowns out the dialog whenever it appears, which is about seventeen or eighteen times.

He’s a mime, too. How do I know that? Because of this sequence, which has nothing to do with anything and is spliced into the movie despite having nothing to do with anything. I doubt even Cullen can explain why it’s there.

Despite his obvious talents, Cullen flies too close to the sun near the end, which involve extended shootouts between krack-addicted klowns and the bounty hunter hired to kill them. It’s just a confusing pileup of people flopping around on the ground for no reason and firing shotguns one-handedly.

Here he’s clearly trying to make a bad movie, and that’s boring. Anyone can make trash: the secret to a successful bad movie is to make trash without intending to. The Room isn’t funny because of “you’re tearing me apart, Lisa!“, it’s funny because that line was meant to hit emotional paydirt. That critical lack of self-awareness is often missing from Killer Klowns.

My favorite bits are the accidental mistakes. One subplot involves a sleazy cult leader making cold calls and scamming people. But we see his computer screen…and it’s 9:52PM. That one moment – a cold-call marketer drumming up business at two hours before midnight – made me laugh harder than all the deliberately crappy special effects combined.

Cullen’s not famous – yet. The world’s not ready for his genius. One day, when he achieves mass success and is being watched by millions of people, I will be there to bask in the glory, because I believed in him. I have a sneaking suspicion that the “millions of people” will be primetime news viewers and his name will be followed by those of the 20-25 people who were in AR-15 range when he finally snapped, but still.

I highly recommend Killer Klowns. It’s not really an ironic bad movie. It’s more an audiovisual experience for when you don’t want to put any effort into watching a film but still want to experience pixels floating on a screen as your brain shuts down. It’s a 2:00am movie, in other words. I like to stay up late, playing this on repeat. My lower lip hanging slack, drooling. My mind completely blank of any thought. It’s hard to explain, but when I enter this state I almost feel like I’ve achieved a psychic oneness with the people who made it.