A single long movie that was split in two because Harvey Weinstein wanted to fuck a potted plant that day (I don’t know). On the surface it’s a movie about kung fu/grindhouse/western tropes of revenge, but equally, it’s about the technique of moviemaking itself. The closest parallel is watching an artist who puts paint on canvas with such consuming skill that the act of watching him paint is as fascinating as the actual painting.

Kill Bill is ingenious, and one of the stronger Tarantino works. There’s hardly any story. From beginning to end, the movie wants to thrill. It’s just cool visual, cool setpiece, cool dialog moment, with only tenuous ligatures of plot and motivation in between. It’s all delivered with ease: some movies try so hard that they seem to sweat, while Tarantino’s, whether good or bad, all have an effortlessness to them. Only later (or upon rewatching) do you become aware of how hard certain parts must have been to film. Although a shorter one-movie version of this would have been stronger, it’s good to live in a world where any form of Kill Bill exists.

Witness the opening scene, which goes from 0 to 100, 100 to 0 (when Vivica A Fox’s daughter interrupts the fight), then 0 to 100 again – sudden gear-changes that have devastating effects on the viewer. The staging, and blocking, and so forth is cartoony as hell, and this almost seems like an effect. There’s an animation technique called rotoscoping that consists of artists painting cels over live-action film. Kill Bill almost looks like reverse rotoscoping, with live actors playing at being comic drawings. The exaggerated swooshes, bangs, and music stabs add to this effect.

But it’s uneven in places. Vol I is much the stronger half. Most of the classic Kill Bill scenes are here – the animated sequence, the House of Blue Leaves sequence, the final boss battle. The climax is absurd beyond absurd, but it’s directed with a slaughterman’s eye for weight and mass, with blood spraying and limbs falling convincingly. Everything makes sense and can be followed on the screen. The decision to film everything “practical” was the right one – watch the Crazy-88 fight and infamous “burly brawl” scene in the second Matrix film (the only comparison I can think of) and the Wachowski film looks like Pixar.

I enjoy Vol II less. It has a slower pace, which allows for some fun Coen Brothers-esque character moments (a lethal assassin who winds down his days cleaning toilets in a strip club), but much of it’s clearly filler, stretching out a too-short movie. Kill Bill was chopped in half, and due to the way the plot is structured, it couldn’t be chopped in half. Most of its skeleton and organs ended up in Vol I. Vol II contains a lot of mush, with about seventy or eighty minutes of movie mixed in.

And it’s visually less appealing. The first part looks drab and overstays its welcome – it feels like we spend a million years in some asshole’s mobile home, and when the Pai Mei flashback sequence occurs, it’s a relief to see some color on the screen again. And it doesn’t really try to recapture the first film’s excesses, which is a shame. There’s 2-3 fights and they end pretty quickly, with only the Elle Driver battle arousing much interest (it also contains the best eye-gore scene since Lucio Fulci retired). And the more grounded tone doesn’t always work to the movie’s advantage. It invites logic into the proceedings, and logic is Kill Bill’s antimatter. “Wait, why is the Bride allowed to carry a samurai sword with her on the plane?”

I enjoyed David Carradine, though. I guess you could say he has a stranglehold on the movie. There’s a lot hanging on him, and its good that he doesn’t choke during his performance. The film really breathes during the moments he’s on screen. I’m glad Tarantino gave him maximum airtime, and didn’t leave him dangling.

In 1997, Don Bluth’s Anastasia was a smash hit, earning $140 million at the box office.

His next film, Titan AE, lost a hundred million dollars, ended Bluth’s career as a film director, and bankrupted Fox’s animation wing. What went wrong?

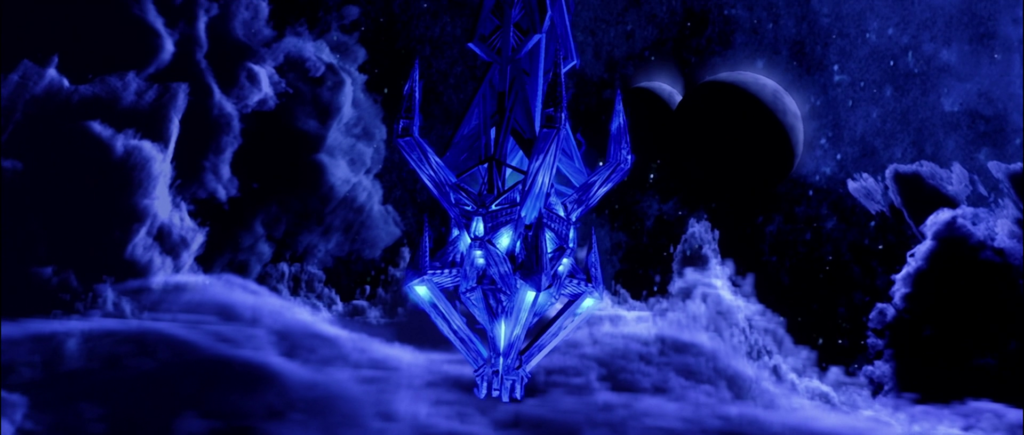

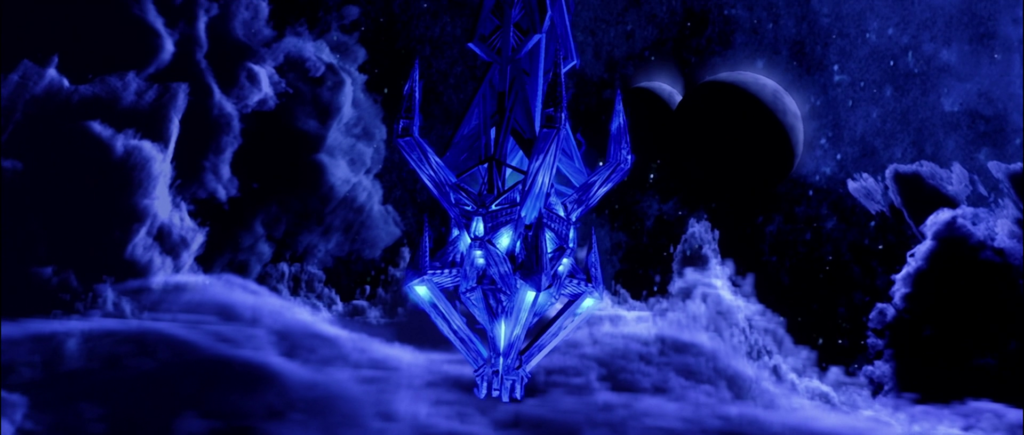

A brief consideration of the film: it’s a science fiction animated feature featuring hand-drawn characters in computer-generated environments. A thousand years in the future, humanity has built a planetary creation device called the Titan, and attracted the attention of a race of energy-based beings called the Drej, who blow up the the Earth. Fifteen years later, the surviving refugees – including Cale Tucker, whose father piloted the Titan away to parts unknown on the eve of destruction – now work as intergalactic miners and scrappers among nearby aliens. It’s a rough universe. If you ain’t got a planet, you ain’t got shit.

The plot is horribly casual and probably a spec script. The narrative is sprinkled with all the expected developments: Cale is sassy and doesn’t fit in, he has to learn to believe in himself, and so on.

The Drej (who are still hunting for the Titan, and believe that Cale is the key to finding it) are blue floating polygons who exist to be gunned down. They’re some of the blandest villains I’ve ever seen. There’s a platonic female love interest who, one gratuitous moment aside (more like Drew BARINGmore, ha ha?), might as well be Cale’s sister. Some depth exists in the charismatic but self-interested Korso, but the film doesn’t know what to do with his complications.

The science fiction setting is Star Wars derived, meaning it’s a WWI/WWII adventure set in space. It’s a world where you can fix up a broken spaceship using spare parts and axle grease. Stowing away on a spacecraft is as simple as hoodwinking a sleepy night guard. Space combat involves dodging laser blasts with a joystick while your attackers ominously beep closer on a green radar screen. It evokes the world of Biggles as much as it does actual space.

Cale’s living quarters contain relics from the lost Earth…but they’re all quaint anachronisms from the 20th century, such as a bisque doll, a hand-cranked camera, and a china cup. The movie seems split between two times. It’s set both a thousand years in the future and a hundred years in the past.

The Titan, when it’s discovered, looks rather like the Death Star, except it creates planets instead of blowing them. Again, spec script. “Borrow ideas from other movies, but twist them so they’re yours”. Likewise, we get Waterworld’s conceit of the hero literally having a map on their body – but instead of a tattoo, the map’s written in Cale’s DNA.

The story didn’t set my imagination on fire, but I’m an adult, and this is a film made for children. Titan AE is edgier than the average Disney film, but that just means its intended audience has an age two digits long. It’s fine to borrow when your audience is encountering most of these tropes for the first time, but it’s a little disappointing, because Titan AE would have worked as an adult film. I don’t mean Heavy Metal style tits and gore. I mean more of a mature, grounded tone, more thought, more wonder, a slower build and a higher climax instead of an endless sugar rush of chases, fights, more chases, etc.

There’s one or two moments where we see the shape of what Titan AE that could have been, like a statue writhing inside a block of marble. I liked the cyberpunk shanty town. And the final scene draws visual inspiration from Moebius’s endless horizon-spanning wastes. But in the end, this aspect of Titan AE is left frustratatingly unexplored. All it shares with the adult animated films of yore is that it made no money.

But storytelling is Titan AE‘s weak point. Its strength is its visuals, which are incandescently beautiful. There’s a ton of great background work, often featuring actual COLOR(tm), which is something Bluth forgets to include sometimes.

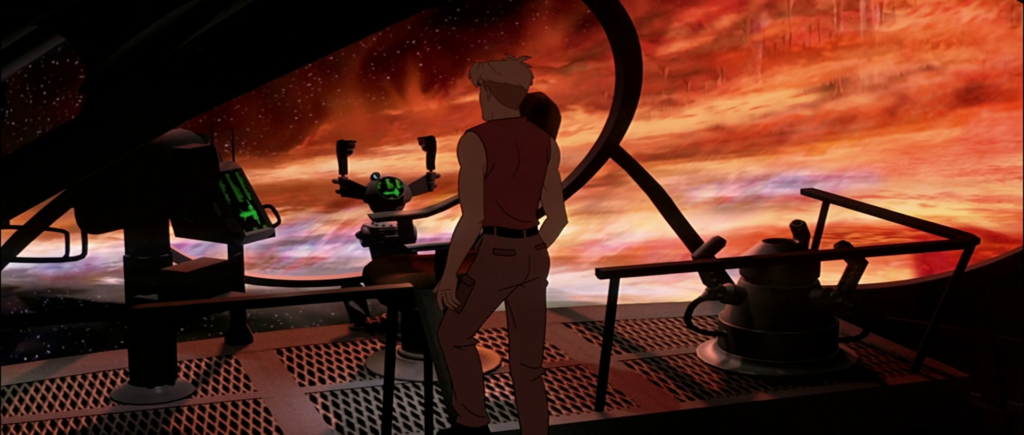

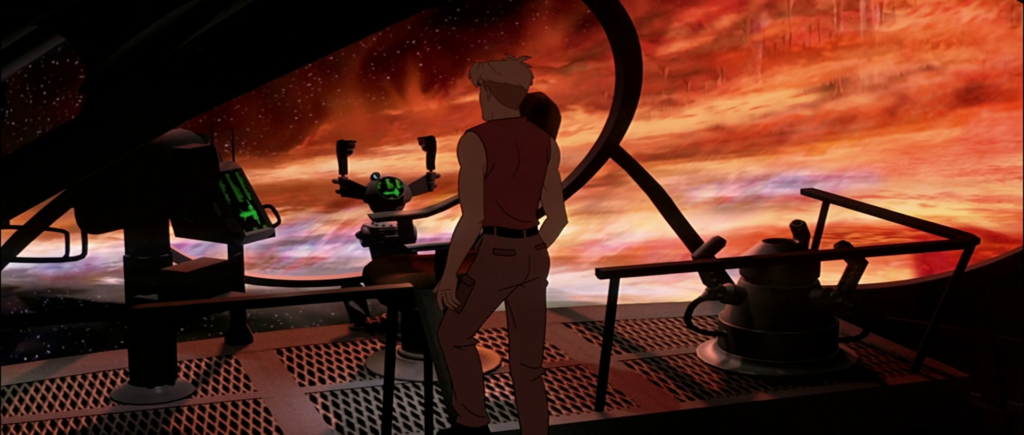

The environments are computer-generated, and the way the hand-drawn characters are composited into them is usually extremely well done. This movie does for CGI what Roger Rabbit did for live action – it puts cel-shaded heroes in a computer-generated world, and has them believably take up space and interact with their surroundings.

Look at the above clip: Korso walks up the stairs of the command deck, weaving his body around obstacles in his path. Out of commercially released animated films up to 2000, only Disney’s Tarzan has a better union of computer-rendered and hand-drawn images.

Animation is an odd thing: in theory computers can render anything. In practice (given you have a budget and limited computing power), there are things they can’t easily do. And these limitations are almost the reverse of live action. In live action, it’s hard and expensive to show a car plummeting out of a burning building. In animation, it’s hard and expensive to show a character opening a door, drinking a glass of water, or adjusting her hair. Animation is a game of how easily you can hide your limits, and Titan AE acquits itself well. Not without sacrifices, though. Screenwriter John August remembers having to write the movie around such directives as “the characters can be underwater, but they can’t be wet.”

Titan AE runs into serious problems in its final ten minutes. The film just ends. It’s like the story abruptly files Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

The Titan is discovered, activated, and instantly destroys all narrative tension. Note that the Death Star didn’t belong to the Rebel Alliance, it belonged to the Empire. It’s hard to make a showdown compelling when the heroes have a weapon of literally godlike power – and it raises questions such as “if humanity was capable of building things like this, why were the Drej ever a threat to begin with?”

The movie ends with haunting visuals of a blank slate of a planet – and a new tomorrow for the human race. It’s pretty, but an artificially simple ending, leaving the deeper implications of the plot unresolved.

Even the film’s visuals suffer in the final minutes. Did they run out of time? Money? Both? How else to explain embarrassing shots like this, where the animated passengers look as flat as postcards (and check out the orange background underneath the third man from the left’s face due to a misaligned clipping mask.).

The film might be the fourth greatest Bluth work – worse than An American Tail, A Land Before Time, and the Secret of NIMH, but (slightly) better than Anastasia and All Dogs Go to Heaven, and much better than all the rest (A Troll in Central Park et al). That’s not bad. It could have gone further. A simple and unsatisfyingly resolved story goes a surprising way when it looks pretty. But far enough?

Despite its many strengths, the film capital-f Failed so hard it took down a production company with it. Why?

There’s one explanation: the film was a perpetual pass-along project that nobody wanted to finish, and once it was finished, nobody wanted to promote it.

But there’s a different and more interesting theory, written by Alan Williams on Quora.

One of the better theories I’ve read about this involves the timing and promotion for the movie.

In May of 2000, “Battlefield Earth” was released…and BOMBED. It was critically panned, it did horribly at the box office, and pretty much became a punch-line overnight. This is a film that is routinely mentioned in conversations of “Worst Movies of all Time”.

A month later, “Titan: After Earth” was released.

Fox had promoted “Titan: A.E.” as “Titan: After Earth” quite a bit before it’s release, and well before the release of “Battlefield Earth”. There was a shift in the ad copy to the “A.E.” tag late in it’s promotion cycle, but it was already out there.

So of course, the theory goes that the somewhat similar titles helped to doom the animated movie.

Personally, I give quite a bit of credit to this theory. It’s sort of hard to understate how BIG “BE” bombed. Cratered. It took a lot of folks down with it for quite some time. Franchise Pictures, the production company, was later investigated by the FBI for artificially inflating the production costs of it’s projects, and thus, scamming investors out of their money. John Travolta was said to have fired his long time manager over issues surrounding the film.

Is it true? It’s plausible, but I’m skeptical. I can’t find any pre-release material describing the film as “Titan: After Earth”. And you wouldn’t think Scientology/Travolta vehicles would have a lot of market overlap with fans of Titan: AE.

Fire a .22 round and a casing will go plink on the ground. If you pick up this casing, clean it, crimp it, fill it with powder, and seat a new primer and bullet, it will be as good as new.

But when you fire and reload the same casing ten or twenty times, eventually it will not be good as new. The metal will become embrittled, prone to cracking and spalling; the walls will be thin, fluxed outward by temperature and pressure; the primer might no longer sit properly; and it will be liable to misfire. There’s variability both in material – in general, brass casings handle repeated firing better than steel or aluminum ones – and in individual casings. Either way, metallurgy will distort your casing past the point of no return. You can never unfire a bullet.

Gunfire changes bullets. It also changes the men firing them. It’s a common pop culture conceit that war irreversibly transforms men – hauls them across an event horizon to sub- or super-humanity. Veterans return to their families and they’re not the same: they quiver and twitch, they’re prone to explosions of anger. Audy Murphy is the US Army’s greatest war hero, credited with 240 kills. He came back a post-traumatic stress case who slept with a gun under his pistol – a gun he would use to threaten and terrorize his first wife. She’s lucky his kill count isn’t 241.

Full Metal Jacket is a latter-day Kubrick film about the above transformation. It depicts the lives of several soldiers (or rather, aspirant soldiers) subjected to the furnace of the Vietnam war. Some crack. Others “survive” in biological terms but jettison parts of their humanity. All seem to have lost something in the end.

It’s fifty percent a great movie. Most films are zero percent a great movie, so that’s not bad. But it’s impossible not to watch it without regret: Full Metal Jacket ends up being much smaller than its shadow. If only it were great all the way through.

Nearly everyone agrees which half of Full Metal Jacket is good. The boot camp scenes at the start – focusing on the relationship between a bullying drill sergeant and a fat, clumsy recruit – are as compelling as anything ever Kubrick put to film. They’re hilarious, cringeworthy, raw, and so thematically complete that when they end, it feels like the movie should also end. It’s actually a surprise when it doesn’t.

R Lee Ermey is fantastic, and carries the movie on his shoulders. He struts up and down lines of terrified recruits like a demonic rooster, reeling off pungently vile insults like stanzas of metered poetry. I’ve heard veterans describe boot camp as “the funniest place you’re not allowed to laugh”, and I think about that when Ermey says stuff like “unorganized, grab-asstic pieces of amphibian shit” and “slimy little Communist shit twinkle-toed cocksuckers“, ready to dump all the shit in the sky upon the first private to crack a smile.

How accurate a portrayal of the boot camp experience is this? I remember a discussion on IMDB’s defunct comments bored – half the vets were saying “This is fantasy” and the rest were saying “This was my experience, exactly.”

Certain things seem right, based on what I’ve heard from friends. Dumping a recruit’s entire kit all over the floor because one little thing isn’t squared away. Punishing an entire class for one recruit’s screw-up. These scenes have a ring of truth. Ermey’s behavior has a cruel kind of logic behind it: he’s weeding out “non-hackers”. In his mind, if you’re going to snap under pressure, you might as well do it at Parris Island, rather than in the field, when the lives of your brothers are on the line.

Vincent D’Onofrio also inhabits his role well: that of a helpless wide-eyed frog getting smashed to pulp by a baseball bat. After weeks of abuse, his eyes start changing, and the drill instructor thinks he’s finally taking instruction. Movie viewers, of course, are aware of dramatic arcs and might guess that something else is coming.

Later, when Joker graduates boot camp and goes to Vietnam, the movie literally loses the plot. None of its events are motivated by anything much. It grinds out some new ideas and characters, but next to D’Onofrio and Ermey’s dynamic they’re not interesting or memorable. I don’t seem to be alone in that assessment. On the film’s IMDB page, the top-voted quotations are overwhelmingly from the early scenes. Down the bottom you’ve got lines spoken in Vietnam by guys I don’t even remember being in the movie.

These scenes are tonally inconsistent. The part where Joker has to write propaganda (“we have a new directive from M.A.F. on this! In the future, in place of “search and destroy,” substitute the phrase “sweep and clear”!) is straight out of Dr Strangelove. Then there’s a moment where a gullible soldier has his wallet stolen by a wacky karate-chopping Vietnamese street gang. Other scenes play their material very straight, without a hint of satire.

A lot has been written about Vietnam, and the way it reflects the final destruction of Clauswitz’s notions of war. No more battle lines. Your enemies dress like civilians. They use women and children, forcing you to make terrible decisions. Your fellow soldiers behave barbarously. Up is down and left is right. You want to escape, but even when you do, the war follows you home, haunting you. What’s it all for?

Kubrick’s film starts out purposeful and ends confused, muddled, and existing just to exist. In this sense it’s the perfect depiction of the Vietnam war.