Living dolls are an ancient fascination. They are storied in every place that has stories, and sung about wherever there are songs. Pygmalion’s ivory bride; Hephaestus’s automata; Hidari Jingorō’s statues; the golems of Prague; Pinocchio; Sir Cliff…we seem fascinated by the idea of soul-sculpting, of lacing gears together so finely that sparks glimmer at the isthmus of the teeth.

Maybe the creation of life—actual life—is the ultimate goal of art. Mona Lisa’s smile is fake. Stare at it, and soon all you see is that it’s odd and uncanny. Leonardo da Vinci was a master, but in the end, he was stuck imitating life, and the reflection of the moon on the water will never be the moon. His Mona Lisa smiles because she has to. Imagine a painting that smiles because it wants to. No artist has succeeded at making a piece of artwork that actually lives. Unless God is an artist: according to Genesis, he formed us out of dust from the ground, so in a way, we’re his dolls.

But is it possible for a toy to live, while still remaining a toy? The point of toys is that they’re not alive: they’re a blank slate you fill with your personality and desire. Researchers at the Kibale National Park have observed adolescent chimps using sticks as toys, but the males use them as weapons or tools, while female chimps cradle them like babies. Toys are just shadows and reflections of their owners. The idea of a living, talking, thinking toy, with a will of its own, is a weird one. Maybe a horrible one.

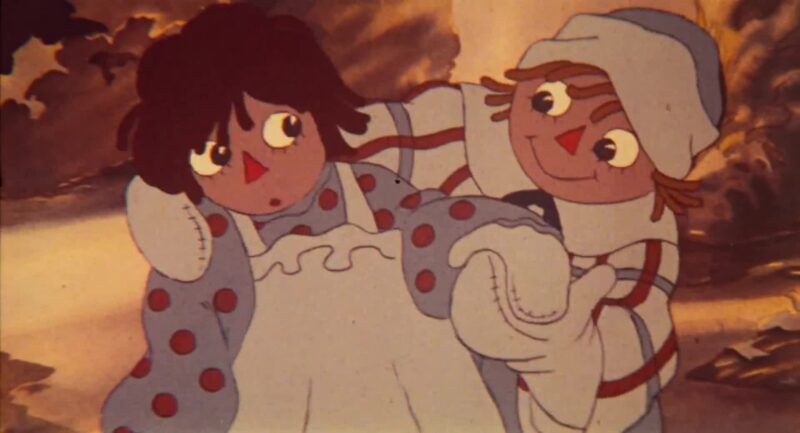

Richard Williams’ Raggedy Anne and Andy: A Musical Adventure is an animated film from 1977. Toys are preparing for their owner Marcella’s seventh birthday when a pirate captain breaks out of a snowglobe and kidnaps Marcella’s birthday present, a bisque doll named Babette. A loyal Raggedy Anne doll goes on an adventure to save her.

The film was a box office bomb, and ended up as airtime filler on CBS and the Disney Channel. It has a thin plot, and relies on beautiful animation and Joe Raposo’s music to carry it. Like all movies about living toys, it has existential implications. The toys in the movie conspire to make the life of children wonderful—that’s basically all that motivates them. Are they slaves? Do they have free will? Do they have the ability to judge? To hate?

The toys in Raggedy Anne and Andy exhibit Nietzsche’s slave morality. They are fully subservient to Marcella, not because she’s nice or worthy, but because of what they are and who she is. But they seem to possess awareness and introspection. Raggedy Andy is ashamed that he’s owned by a girl. The Twin Pennies are curious about what life is like outside the playroom. Most disturbingly, Raggedy Anne feels pain and discomfort at Marcella’s rough playing—the first thing she does is complain that she’s popped half her stitches. However, they seem to be at peace with their place in the universe. They can’t imagine freedom. The only characters who rebel are Babette and Captain Contagious, the villains.

The movie is charming, and lavishly animated by 1970s standards (until the production ran out of money—believe me, you’ll notice when this happens.) Of special note are Tissa David’s sensitive Raggedy Anne, Art Babbitt’s Grecian-tragic Camel With Wrinkly Knees (with each of his humps embodying a different personality), Emery Watkins’ voracious sucrose ocean Greedy, and the typical brilliance displayed in Richard Williams’ “No Girl’s Toy” sequence.

But it’s shamelessly schmaltzy, and feels decades older than 1977. I’d always assumed Raggedy Anne dolls were based off Anne of Green Gables (red hair + freckles), but this is not true. This is a movie based on a doll patented in 1915, and then a children’s book written in 1918, and you really feel those years. Raposo’s music is straight out of Tin Pan Alley.

The film was (possibly) funded by the CIA. It was distributed by the ITT Corporation, a shady manufacturing conglomerate with ties to the US executive branch: their involvement in Augusto Pinochet’s coup is now well-established. This was around the time the CIA was waging a so-called Cultural Cold War, which involved promoting “American” forms of art such as Broadway musicals. The source of funding was apparently an open secret among the film’s production team. Here’s a second or third hand story shared by Steve Stanchfield (by way of Garrett Gilchrist):

(Not speculation at all). Talked with Dick [Williams]. A friend had visited him and talked about how the CIA had funded the film. When I was talking with Dick about Emery [Hawkins] being fired, I asked if that was the CIA. Dick’s hands went in the air and he said loudly “those were the guys!!” and started to tell a story. His wife quickly came over and said “we’re not going to talk about that right now”. Later, while I was at the national archives searching for Private Snafu materials, I made a request to see material related to the CIA, ITT and Raggedy Ann and Andy. The freedom of information act is a wonderful thing. ITT was in trouble in GB and the states for being a front for the CIA. This led to the assassination of a candidate in South America, leaving egg on the face of ITT. They produced some childen’s programing to show they are a solid company with family values (and, of course, that idea is as ham-handed as it sounds). The programs were the Big Blue Marble and the animated feature Raggedy Ann and Andy. Raggedy Ann was to be released, at the latest, in the summer of 1976, in time for the big celebrations for the Bi-Centennial of the US. ITT bought Bobbs-Merrill for this purpose. Once the film was finished, they sold the Raggedy Ann film for $10 to Bobbs-Merrill and, somehow, allowed their assets to be sold back to itself. It is now owned by Random House. This is public record, and there’s many, many pages (thousands). I’ve just seen a handful.

If the ITT Corporation was indeed a spinnerette for taxpayer money, this could imply that part of the film belongs to the US public—ie, it’s public domain. As a pundit joked when obscenity charges were brought against a Robert Mapplethorpe photo of a flaccid penis, it probably won’t stand up in court, but I definitely feel less guilty than usual about giving this film the Captain Contagious treatment, if you know what I mean.

I’ve watched it once, and may watch it again. I maybe I won’t. Raggedy Anne and Andy is pleasant, but it’s not an unsung masterpiece.

The pacing is terrible. The film larded down by musical numbers—we get SEVEN songs before the first vestiges of plot emerge. It’s a “Musical Adventure” with MUSICAL in all caps and (adventure) in tiny-sized font. The small story is episodic. Raggedy Anne and Andy make a new friend, get into trouble, escape somehow, then repeat. Again and again.

But the movie’s flaws—the leisurely pace and incidental storytelling—do capture what it’s like to be a child, cooped up indoors on a rainy day, playing with your toys and making up adventures for them in your head. Or rather, what it once was like to be a child.

What would a kid born in a year starting with “201” think of this film? Would it provoke wonder? Or would it simply seem as an alien relic, undecodable and indecipherable? When I see children today, I am struck by how few of them still play with toys. Instead of Raggedy Anne, their hands are wrapped around a glowing shard of magic glass. It sings to them, enchants them, dreams for them, hurtles them algorithmically into an adulthood they’re not prepared for. Young girls are memorizing rules on how to diet and dress and say correct words and have correct thoughts. Their brothers watch aspirational lifestyle videos by a bald sex predator. The past depicted seems strange, but that’s not true: the world of 1977 is set in stone, remaining the same forever. We’re the ones who are strange. If there’s any character that represents today’s society, it’s the Greedy.

This movie will look like footage of a remote jungle tribe someday. Maybe that day has come already. It depicts a world and lifestyle foreign to us, a past that has come unraveled like Raggedy Anne’s stitches. For this reason alone, it’s worth watching—or at least, knowing about.

The abduction scene is fantastic; six minutes of such sustained, unrelenting horror that it almost melts the lens. It might have been better to not show so much of the aliens (they look like Baby Groot), but I’ve never seen such a good evocation of how a nightmare feels from the inside. Shadows: screams; reality slipstreaming away like oil; visceral helplessness. I felt like a mouse dying in a cat’s mouth.

It’s good that Fire in the Sky has that scene, because the rest of the movie isn’t worth a tinker’s damn.

It’s a poor man’s Twin Peaks (Twin Molehills?) about lumberjacks who witness a UFO. The narrative focuses on their emotional journeys as they unpack this experience. Will they come to terms with what happened? Will the townsfolk believe them? Will Flannel Guy #1 mend his feud with Flannel Guy #2? And so on.

On any reasonable scale of importance, “alien visitation” scores a 9.7 out of 10, and “personal dramas of a small-town yokel” scores a 1 or a 2 (unless the small town yokel is you, in which case you might bump it up to a 3). These characters are not interesting and almost cannot be interesting next to the movie’s inciting event. We’ve seen aliens. We do not care about anything except the aliens. Can we talk to them? Reason with them? What do these fey goblins from beyond the void want? Maybe the movie’s point is that there are no answers: that things just fizzle away inconclusively. If so, it fails to fill that silence with anything compelling. It delivers a flat and unengaging soap opera.

The script is wrong, and I wouldn’t know how to fix it. It has one interesting event, which happens at the start, and most of what follows is setup for a joke whose punchline we’ve already heard. This repeatedly causes problems. For example, the movie expects us (the audience) to care whether the lumberjacks pass or fail a lie detector test. But we already know they’re telling the truth (we saw the spaceship!), and thus there’s no tension to the scene. It’s as dead as a dynamited fish.

One of my favorite horror books is Picnic at Hanging Rock, which tries something similar. A mystery at the start goes unresolved, until a town almost shreds itself apart on the axle of that question. You should read it. It’s one of the classics that lives up to the hpye. Hanging Rock was able to blend form and content in a compelling way. The town in that story seemed to be collapse into weird cultlike denialism that was as creepy as the disappearance itself. You’re almost convinced that certain people know what happened, and want it forgotten. The mix of rage and helpless confusion is palpable, and finally infects the viewer. We share in the town’s disease.

Fire in the Sky, by comparison, is made of standard soap opera ingredients. It tries to tell a small, personal story, but does so against a speculative backdrop that’s far more interesting. Imagine a man filming a fly, with a nuclear bomb detonating in the background. Why would you zoom in closer on the fly? The film produces frustration, then momentary horror, then frustration.

It’s based on a true story. I wish I could send this movie back to my 12 year old self. He would have loved it.

I was obsessed with UFOs and alien visitations. I read every book I could, and could recite the “classic” abduction stories (Barney and Betty Hill, Allagash, Strieber, Vilas-Boas) chapter and verse. I’m surprised I didn’t remember the Walton account (which forms the inspiration for this film), but I’m sure I once knew of it. I used to stare up at the sky, and hope to see fires of my own.

Then I grew up, and did as the Bible commands: put childish things away.

Questions are an addictive drug. Once you start asking them, it’s hard to stop. Why do descriptions of aliens always mirror contemporary Earth technology and interests? In the Middle Ages, UFO sightings were of crosses or glowing balls. In the early 20th century, they looked like airships. Now that the “flying saucer” meme is firmly embedded in our cultural neocortex, that’s all they look like. The appearance of the aliens themselves tracks closely with how they’re portrayed in popular culture. Skeptic Martin Kottmeyer acerbically noted that Barney Hill’s abductors (as described by him under hypnosis) bear striking similarities to a monster in the previous week’s The Outer Limits.

And is it likely that an alien race would be bipeds with multi-fingered hands, two eyes, one nose, et cetera? Is it likely that we would be able to breathe their air, and they ours? How could a race of aliens clever enough to avoid detection by the combined firepower of NASA, SETI, and 12 year old Australian boys with binoculars be so clumsy as to be seen by Walton? Where does the invasive “probing” trope come from, if not our horrors of animal vivisection? Wouldn’t they be able to learn about our anatomy through radiographic imagery? And so on.

I still regard UFO stories as interesting (they’re too common and culturally universal to ignore), but they are probably a psychological artifact—the call is coming from inside the house. Aliens might exist somewhere, but barring a revolution in physics, I expect their civilization (or ours) to die in the shadows of space before we ever encounter each other. The only alien intelligences we are in contact with are the homebrew ones at OpenAI and DeepMind. And yet…

“Oh, those eyes. They’re there in my brain (…) I was told to close my eyes because I saw two eyes coming close to mine, and I felt like the eyes had pushed into my eyes (…) All I see are these eyes…”—testimony of Barney Hill

…The best UFO stories—and notice that I don’t specify whether they’re true—have a horror pulsing under the skin that leaves me enthralled. They’re signposts pointing to a very dark place: either out into the chill of space, or inside, into the wilderness of our minds. No matter what you believe, we cannot escape the horror of not being alone. “The last man on Earth sat alone in a room. There was a knock on the door.”

This is a great movie to watch with 30-40% of your concentration. If you are doing your taxes, texting a friend, and watching the dog chase a ball around, you will enjoy Spider-Man II. Good director. Good action sequences. The colors pop. But believe me, you don’t want watch this movie with your full attention, like I just did.

Nothing makes sense.

- Peter Parker swings from webs that come from above the city skyline. What’s he sticking those webs to? Passing planes? The moon?

- Peter Parker throws two robbers out of a car as Spider-Man, and then drives the car to Mary Jane’s recital. When he arrives, he’s dressed in a suit. The implication is that he dressed while driving, like Mr Bean.

- Who rebuilds Doc Ock’s lab after it’s destroyed? What contractor would work with a fugitive from justice who is wanted for murder?

- Why is Doc Ock even able to return to the lab? Shouldn’t there be cops or security staking out the scene? How is he able to wander around the city without attracting attention? How does he conceal four 20-foot metal tentacles the size of sewer pipes under a coat?

- Doc Ock needs money to rebuild his lair, so he robs a stereotypical Movie Bank(tm) with a vault full of bags of money like in a literal cartoon. The bags spill open to reveal…gold coins. What’s he going to do with those? Nobody takes payment in gold coins. Is this a period piece, set in 17th century Tortuga?

- The train is literally the monorail from the Simpsons. Doc Ock destroys the brake lever (not the brakes themselves, mind you. The lever.) The train then accelerates out of control, as indicated by a speedometer with a helpfully gigantic SPEED INDICATOR label.

- Why doesn’t Doc Ock build body armor? Or wear a kevlar vest? Or even button up his shirt? He’s the most vulnerable supervillain I’ve ever seen. A good-sized potato, properly flung, could stop him.

- Peter Parker tries to stop the speeding train with his legs. Even the extras on the train remark that it’s a stupid idea.

- Doc Ock snatches Aunt May out of a crowd and drags her to the top of the building. What does he need her for? He doesn’t know at this point that Peter Parker is Spider-Man. To him, she’s just some random lady.

- In the ensuing fight, Spider-Man catches Aunt May with a web as she falls. He then whiplashes this 70-year-old woman back upward with the kind of G force that would get a trained pilot invalidated for six months with ruptured blood vessels. She ends up comically hanging from a statue by her cane, while emitting mild, unconvincing screams.

- Doc Ock tells Peter Parker “bring Spider-Man to me!”…and then flings Parker into a brick wall at a speed that might easily have killed him, rendering him unable to carry out the instruction.

- Doc Ock incapacitates Spider-Man, ties him up, and drops him off at Harry Osbourne’s pad. He doesn’t take two seconds to lift Spider-Man’s mask and learn his identity. His ties are so weak that when Peter Parker wakes up he breaks out with no apparent effort. I guess Doc Ock just got lucky that Spider-Man stayed unconscious for exactly the right amount of time.

- If Peter Parker is strong enough to hold an entire steel-framed wall on his back, why is he working as a pizza delivery boy? The man could do the work of a crew of Teamsters.

- When Peter Parker abandons his Spider-Man alter-ego, crime increases by 75%. Note that this isn’t “robberies” or “murders”. Just “crimes”. I guess tax evasion and mortgage fraud are also going through the roof in Spider-man’s absence. (Note that in 2004, New York had 1,425 crimes per day, about ten to twenty times greater than Movie!New York’s crime wave.)

Etc. This was just death by a thousand cuts for me. It doesn’t help that it’s “superhero loses his superpowers”, my least favorite plot device.