A kid is frequently just a lock waiting for a key. In 2006, I found my key when I discovered Rob Zombie. I became obsessed with his music: he was the only thing I thought of for about a year.

I went deeper on him than anyone should go without a fedora and a $200-a-day-plus-expenses account, making it my business to know about every obscure B-side, every film soundtrack contribution, and every guest appearance. I knew that “Dragula” was originally titled “West of Zanzibar”. I knew about the infamous La Sexorcisto promo cassette which contains extra samples cut from the final album because of usage rights (here’s some of it). I knew which scenes in House of 1000 Corpses were filmed in Rob Zombie’s apartment after the budget ran out. I even defended Educated Horses on internet forums, which is like waving a saber and making a Banzai charge for a nation that has already surrendered. An early version of this site was named after a Rob Zombie track.[1]I had a recurrent dream where Rob Zombie and I hang out. Picture this: he’s in the studio, just a shambling mountain of hair. I’m a kid, down on the floor, untangling XLR cables. I hear … Continue reading

At a certain point, the key no longer fit the lock.

What happened? I grew older, and listened more broadly to metal and punk. I heard the original issue: things like Killing Joke and Ministry and Siouxsie Sioux made Rob Zombie seem like a plastic knockoff with a ‘made in China’ sticker. I noticed things about his persona which suddenly struck me as lazy or shlocky or contrived. As late as 2009, I would have still cited him as my favorite musician. But I’d officially become that fan: the one who writes one word of love for every nine words of criticism.

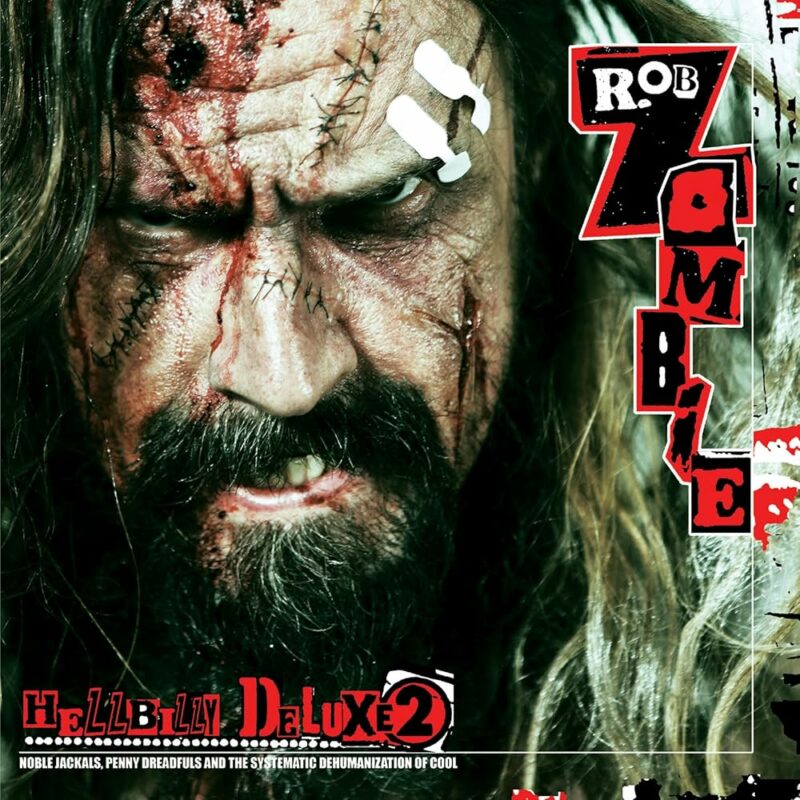

In 2010, I had to face the facts. Rob (after a few years of making unwatchable Halloween cheapquels for Dimension) had returned to music with Hellbilly Deluxe 2. I listened to the lead single “What” and didn’t like it. Then I streamed the album, and found myself skipping around with a weird mix of disinterest and panic slamming in my chest. Things had shifted, and I hadn’t known it.

Yes, “Sick Bubblegum” and “Werewolf Women of the SS” made me smile. “Mars Needs Women” grew on me. The rest just seemed like overly complicated and fussy arrangements of nothing. Boring. Longeurs from a fading shock-rocker who once grabbed and chokeslammed your limbic system. Huh, I thought to myself, I guess I’m just not a fan of this guy anymore.

Around the same time, I’d noticing a trend of fans being unusually prone to turn into haters further down the line (and the bigger the fan, the bigger the hater). The defining example of Fan-to-Hater Syndrome is DawnOWar, an obsessive Manowar fangirl who knew the band since the 80s, ran their website for years and years…and now has no involvement with the band beyond trashing them from every social media website that will platform her. From her Facebook page:

Manowar canceled Detroit! I see this as a victory! Maybe Manowar fans are finally going to stop letting the band rip them off.

Manowar fans complain endlessly about Joey wasting time on stage with his endless stupid long-winded speeches, so hes decided to go on tour without a band and charge $50 for the privilege of seeing him do just the part everyone hates the most. I feel like now is a good time to let your tomatoes start rotting so theyll be ready for throwing when he comes to your town.

This group is not very active but disgruntled Manowar fans PM me all the time to tell me whatever stupid thing the band or the fans did today. I quit working for Manowar at the end of 1999 because they’re jerks. Thank goodness I don’t have a need to still discuss it ad nauseum. Because thats shit that happened to me 15 fucking years ago. But I set up this group to unite the people who do have a need for this discussion. Because they are assholes, you have been suckered out of your money, and they havent been good since 1987. So post that shit here. Its what its for. Don’t PM me to tell me theyre jerks. Believe me, I know. I’ve known for 15 years. Thanks.

I never ended up disliking Rob Zombie this much. But the “fan to hater” pipeline has cast-iron welds and seldom leaks.

I think fans turn on their idols for a few reasons. Hyperfixated fans tend to be extremely aware of flaws in their God. It’s the scribal priest’s lot to copy translation errors in the Torah, after all. They also are extremely aware of the unsavory parts of their idol: the stuff that gets swept under the rug. Every famous person has scandals and drama in their past (or present): the superfan’s dubious reward is to sooner or later discover where these skeletons are buried.

Also, most musicians have public personas that are partly fake: they neither represent who the artist truly is, nor survive close scrutiny even on their own terms.

A gay listener seeking “representation” can’t avoid noticing that all of David Bowie’s public relationships have been with women, that all of Katy Perry’s public relationships have been with men. Depressed introverts always turn out to be media-savvy hypemen and self-promoters behind the scenes. Quirky oddballs always turn out to be quite sane and normal. The persona is often what attracts the fan in the first place: but the more you stare, the more fake and hollow the persona becomes (and where does that leave your love?)

Obviously Rob Zombie’s “thrifted from a Halloween store on November 1” aesthetic is a shameless, gleeful celebration of fakery in all its positive forms. That’s not an issue. But other things about his life might also be untruthful. There was a fascinating Reddit comment that I sadly can’t find now (referenced here) kind of picking apart his often-told “I was with a travelling carnival as a kid and saw a man get murdered with a hammer” story, arguing (believably) that it was implausible for such an event to happen in a small community without being reported in the news, and that some other parts of Rob’s given history are also unlikely to have happened as he describes them (that they are heavily embellished, at best). I do not know the full truth of this, but no star can help but to be a real person, and usually a far more boring one than the one they pretend to be.

While I never hated Rob Zombie like DawnOWar hates the band that she once loved enough to name her internet handle after, I quickly realized I was no longer very interested in him. This was part of a growing process—one that inevitably led to me quite enjoying Rob Zombie again. Such is the path of enlightenment.

Anyway, shall we discuss the album?

It finds Rob re-convening with most of the same guys who gave us the all-filler-no-killer midsterpiece Educated Horses: drummer Tony Clufetos, producer, and (most worryingly) guitarist John 5.

I have mixed feelings about John 5. He is a guitar virtuoso but not a compelling writer of riffs or melodies, as any of his fourteen or so solo albums will demonstrate. His bluesy, elaborate, tasteful style never meshed well with Rob’s vocals. (Happily, Mike Riggs and his simple caveman style are now back in the band, and the three songs released from the upcoming The Great Satan sound absolutely fantastic.)

Rob is not really a musician. That’s an important detail to understand. He arranges and produces and makes loops and supplies the overall artistic vision, but he does not actually write music. I remember this quote from Astro Creep 2000 guitarist Jay Yuenger on Rob’s songwriting “process”.

Later, around the time we were making Astro-Creep and after, Rob started to really hate anything with any kind of melody in it – he was always saying, “Can’t you just go ‘chunka chunka’ there?”, and I’d say, “This isn’t a drum, it’s a GUITAR, it’s got NOTES” He’d want to use techno loops for everything, cut all the music out of it, and that was a situation which went from difficult to impossible.

So that’s the outer limit of Rob’s musical skills: telling guitarists to go “chunka-chunka”. He is heavily constrained by the musicians he chooses to work with. Fun guitarist equals fun record. Boring guitarist equals boring record. This album has John 5, hence it is quite boring.

The album has little of the fun electronic/industrial loops that characterize the classic White Zombie sound. It’s just straight-ahead heavy metal for the most part. It is a bit more elaborate and arranged than Educated Horses, and there’s a primal heavy whallop that’s nice to hear again after acoustic guitars or whatever.

But it’s ultimately just not fun. It’s dated and unengaging: a churn of guitar sludge, over dry drum beats that move at a sauropod’s pace. It simultaneously sounds empty and overstuffed with surface details.

Tedious Down/Black Label Society backwash like “Jesus Frankenstein” and “Virgin Witch” and “Burn” scream and vulcanize with guitar overdubs: flashy fretboard wizardry that ultimately feels like car keys being jangled in front of your face: these songs have nothing interesting going on at a structural level. The riffs are lazy bluesy affairs that sound like things any beginner guitarist could come up in their second or third month of playing. The drumming is pedestrian. The musical ideas are all obvious, borrowed, and done to death. Listening to this music feels like wandering through a dry and parched desert.

“What” is stale Misfits worship with a blaring farfisa organ and a lo-fi, bitcrushed-to-fuck vocal track (another trick Rob has used since the White Zombie days, though now it finally grows old). It seeks to conjure a live and raw monster-punk energy, but Scott Humphrey’s overbearing wall-of-sound production does not ever feel like a band playing. It’s as unconvincing as the fake crowd noises in “Jesus Frankenstein”.

“Werewolf Baby” rocks out with bland and instantly-forgettable slide guitar that kind of sums why John 5 didn’t work in this band. Yes, he supplies some “diverse” elements (Rob was fond of stating that his guitarist could play any style of music), but it’s always the most generic, lifeless version of whatever that thing is. Want bluegrass picking that’s boring? Banjo strumming that’s boring? Arpeggio runs that are boring? John 5 is your huckleberry.

“Death and Destiny Inside The Dreams Factory” is just “What” again. A grim studio confection trying to imitate a live band playing—trying so hard you can see sweat dripping from the sound engineer’s fingers. More distorted vocals. More random guitar overdubs and punch-ins to disguise a lack of ideas.

The three songs I mentioned earlier are pretty good and basically pull their weight. “Werewolf Women of the SS” is a fun “Misirlou” knockoff, though (like the rest of the album) it feels a few bpm too slow. “Mars Needs Women” and “Sick Bubblegum” slap pretty hard. I also don’t mind “The Man Who Laughs”, which is nicely arranged and strung. It avoids Rob’s longstanding distaste of guitar solos by giving Tommy Clufetos a…drum solo. Talk about out of the frying pan.

Real talk, though: there is no “Dragula” and no “Scum of the Earth” and no “Electric Head Pt.1 (The Agony)” and no “Black Sunshine”. I can’t believe I’m saying it, but it doesn’t even have a “Let It All Bleed Out” (one of Educated Horses‘ rare Ws). If you like any of the above music, keep moving, traveller. Two vast and trunkless legs of stone stand in the desert. Nothing beside remains.

Rob himself was seemingly dissatisfied with the album. In 2011, he released a new version, with some new songs. All are quite bad.

“Devil’s Hole Girls And The Big Lack of Inspiration” is a faded Xerox of “Superbeast” with some snarls and attitude but no real hooks or catchiness. There is nothing else to say about it. I hope nobody had to give up too much of their Sunday afternoon to get this one recorded and in the can.

“Everything Is Boring” is a rare piece of social commentary—musically it’s a drab miserable slog, as unwanted as black water regurgitated from your shower drain (and equally unpleasant to wade through). The socially-aware lyrics fail to land, as both the song and the album exemplify everything Rob is complaining about.

The reissue also removes the drum solo from “The Man Who Laughs” (possibly because Tommy Clufetos was out of the band). It is replaced it with several minutes of almost transcendentally uninteresting mandolin strumming (presumably from John 5) that literally sounds like those AI-generated “10 hour Appalachian folk mix to relax to” flooding Youtube.

The matter of “worst song of the album” is resoundingly locked up by “Michael”, which is basically unlistenable and a career lowlight. “Mama, why do I want to kill you?” Oh, shut up. This song is hateful. This is what cancer has regular early prostate exams to detect.

Rob has released better music both before and after this album (though far more in the “before” column, if we’re being honest). But it did introduce me to certain realizations about art and fandom, and for this, I am thankful. Intense fascination can disappear in an instant (or sour to hatred), and probably only stems from emotional problems. Go listen to your inner child: they’re probably less dull than “Cease to Exist” and “Everything is Boring.”

References

| ↑1 | I had a recurrent dream where Rob Zombie and I hang out. Picture this: he’s in the studio, just a shambling mountain of hair. I’m a kid, down on the floor, untangling XLR cables. I hear him murmur “something about this isn’t working…any ideas?”, so I swallow my fear and say “maybe the mix needs more ‘brown’?” (technical audiophile terminology, don’t bother to try to understand it). One of his entourage says “maybe your face needs more ‘shut up'” but Rob holds up a hand. “Wait, let’s hear him out. More ‘brown’, you say? Huh, yeah, let’s try that.” After the session ends, he gives me a little nod, like I see you, and then we go for a walk together. He says “y’know somethin’ kid? You’re like a younger version of me. One who’s not so jaded and burned out. Let me give you some life advice. In this dog-eat-dog world, you’ve gotta keep your chin up and remember to stop and smell the roses, because life is short and time flies.” I absorbed his wisdom as we stood under a streetlight’s bladelike beam, which was suddenly full of prettily glinting snowflakes (it was summer in Australia), and then we leaned into each other’s space and our lips touched. I’m glad I only thought this paragraph instead of typing it. |

|---|