Liked it when I was a teenager. Still like it now. I was born with correct opinions.

Fast, fast, fast power metal, driven by pummeling double bass and wild guitar-shredding. Thousands of notes blast out, stinging and singing like flocks of golden birds. As a kid, I couldn’t believe what what I was hearing. “There should be a law.” If guitars had human rights, both Sam Totman and Herman Li would be trading harmonica solos on death row.

Later discoveries like Galneryus, Vai, Satriani, Gilbert, Shrapnel Records, Yngwie, Buckethead, and even stuff like Nitro would make the DragonForce blitzkrieg sound more ordinary. But when you’re sixteen, this album does to the ears what Arnold Schwarzenegger does to a rainforest in Predator. Not every bullet kills, but they fire a million of them. When I heard Li snapped a string recording the final solo for “Through the Fire and the Flames” (it’s at 6:57—that BROINNGGG that sounds like a saxophone flutter), my first thought was “you mean there were five strings that didn’t snap?”

It’s an assault of notes, with the metronome stuck at exactly 200 bpm (fifteen years later, I’m still mentally reliving an argument I had with a guy last.fm who insisted they’re 100 bpm, because that’s what iTunes told him. Are your ears painted on, bro?). Singer ZP Theart is the steel truss rod supporting the album amidst the chaotic 16th note tapping and sweeping. Without his lead melodies, the enterprise would collapse.

Inhuman Rampage is a real “guitar” album, but few serious guitar players enjoy them. DragonForce never had a chance at being cool: they rocketed to fame in 2006 after a song of theirs appeared in Guitar Hero 3. Truly, the roads to metal immortality are as many as the stars in the sky. Varg Vikernes killed a dude. Glen Benton razored a swastika into his forehead. DragonForce, the absolute madmen, got a song on Guitar Hero 3.

“Through the Fire and the Flame” was their breakout hit. It’s a very good song, though I imagine they regretted writing the intro, because they have to play the song at every show and thus must take a nylon-stringed classical guitar on the road for the rest of their careers. But then there’s “Revolution Deathsquad”, which is even better. And “Operation Ground and Pound” is better again. There’s no actual compelling factual reason “Fire” escaped containment and became their career-defining song, except by circumstance. It could have been one of about four other songs.

Inhuman Rampage is consistently high-quality, but it’s all the same kind of quality. This is the other problem with DragonForce: they tend to burn out the listener. One of the album’s best tracks, “The Flame of Youth”, bounces off you because you just heard “Cry for Eternity”. But it’s a wonderful song, with a great keyboard solo from Vadim Pruzhanov (an underrated member of the band, along with Dave Mackintosh and his nimble drumming). I recommend mainlining only three DragonForce tracks at a time. There’s a lot of ideas and creativity on display, but it’s all culled from the same part of the songwriting amygdala. If DragonForce all sounds the same to you, it’s because you’ve overlistened to them, and your ears have grown a callous.

The album ends with “Trail of Broken Hearts”, which I don’t think I’ve ever listened to all the way. It’s a Poison/Motley Crue style power ballad that doesn’t really work: it sounds too clean, without that whiskey-and-cigarettes roughness that Axl Rose and so forth sometimes bring to a power ballad. But do get the Japanese edition, or whatever version has “Lost Souls in Endless Time” as a bonus track. That song is just nuclear.

It’s easy to turn a corner with this band. First you love them. Then you regard them as videogame sounding trash. Then you love them and regard them as videogame sounding trash. Corners, man. Keep turning them and you’re back where you started.

But I never hated this album. It feels like the purest distillation of DragonForce, and perhaps of power metal. The moment in the storm when there’s more rain touching your face than air. Terrifying, unendurable, but brilliant in its purity. An experience not to be missed.

There’s an art approach called horror vacui—literally, “fear of empty spaces”—where every square inch of the artwork is filled with super-busy linework, as though there are ghosts that might lurk in blank spaces. There’s another style called Wimmelbilderbuch—literally, “teeming picture book”—where an image seeks to contain an entire book’s worth of content: gaze into it, and you’ll see tiny lives, little threads of story spun out and then snipped off. The most famous Wimmelbilderbucher are Martin Handford’s Where’s Wally puzzles, although Hieronymus Bosch could surely be mooted as an early example of the style.

Where does that leave DragonForce? Between the two. Horror vacui is frantic nonsense, endless jabbering so you don’t hear the quiet, and it has pessimistic undertones. Wimmelbilderbucher are wholesome puzzles or fascinating slices of life. DragonForce makes bright optimistic music, made for teenagers and videogames and teenagers who playe videogames, but their intensity borders on a horrific edge. The shredding soon no longer registers as guitar playing, but rather the endless teeming of a million maggots, coiling and uncoiling in viscera. That sounds like a weird comparison, but I find the sight of masses of maggots deeply fascinating. If you are the sort of person who doesn’t give a fuck about finding Waldo, but just likes staring at those impossibly packed yet dead (or beyond dead—they never had a life) people, then give DragonForce a try.

Yeah, Guitar Hero 3 was a mixed blessing. Yeah, they became a laughingstock at a certain point. I heard “FagonForce” and “DragonFarce” so many times that I started keeping my appreciation of them to myself. The image of a locked vault with a firestorm raging behind it proved prophetic. But this is special, special music to me.

(I just looked at the cover for the first time ever and saw that it’s actually not a locked vault. Oh.)

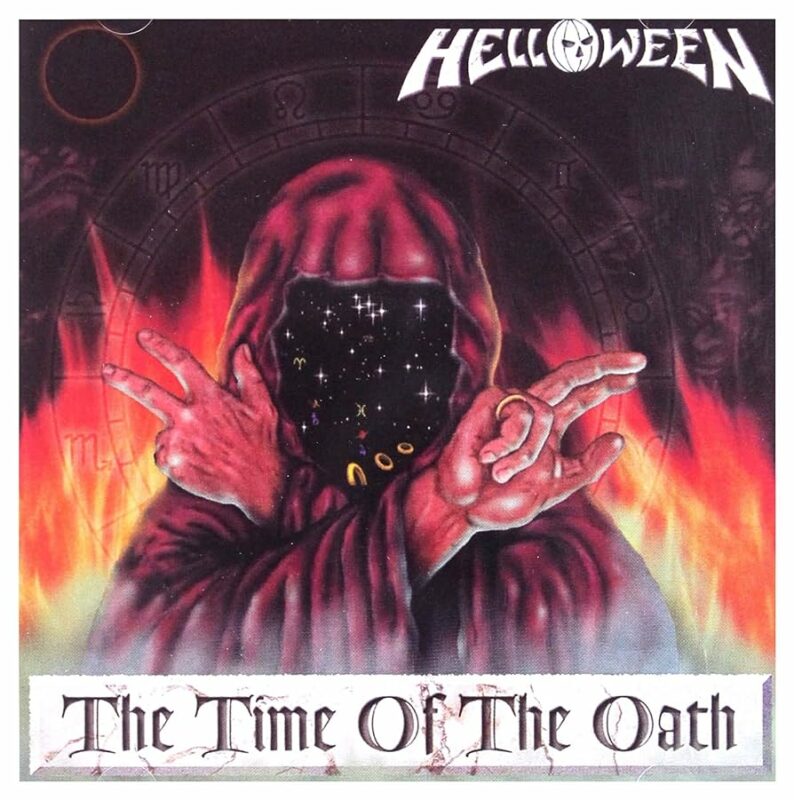

German power metal was in resurgence in 1996, and its founding band resurged along with it. If Master of the Rings was an uncertain but interesting trial balloon for a new lineup, The Time of the Oath marks the point where they fully recovered. Helloween is back. No caveats, no qualifiers. They are back.

A concept album supposedly inspired by Nostradamus (particularly Quatrain 634: “many metal bands shall blatantly lie about being inspired by Nostradamus”), it was their longest studio album up to this point, aside from Chameleon. It definitely feels very long, and arguably moves with too slow a step. The final three songs are all epics, running 20 minutes in total. At times it’s exhausting, like listening to latter-day Iron Maiden.

But it’s music of grandeur, music of the ages. It feels weighty and massive, ringing out like a huge bronze bell. Obviously the two Keeper albums are holy classics, but the goddamn things end as soon as you put it on. By contrast, Time of the Oath is a deep pool you can sink into like a stone. It has humor and lightness and deftness: the large number of songs allows them to explore many tones and moods. Not all of these work, but in online forums I’ve often found myself defending its flaws, which I’ve grown to like.

“We Burn” is a scorching fireball of an opener, and “Steel Tormentor” is scarcely any slower. Deris drives these songs with his trademark verve and attitude, snarling around the microphone like a wolf. “Wake up the Mountain” opens with a Niagara-like torrent of notes from Roland Grapow. Time of the Oath marks the last time he tried to be Yngwie Malmsteen on guitar, before settling into a more blues-influenced style. The rest of the song is a stately midtempo rocker that reminds me of Rainbow.

Andi Deris dominates the songwriting here, composing two of the three best songs, “We Burn” and “Before the War”. The latter is a raging power-metal track that rolls the clock back to 1985, when Walls of Jericho came out. Kai Hansen would be proud to have written this (although he already had much to be proud of—Gamma Ray really hits its stride around 1996, too).

The album gets a bit weak in the middle. “Kings Will Be Kings” and “Power” have never especially grabbed me, and “Anything My Mama Don’t Like” is a pointless Deris-written hard rock song. Michael Weikath’s “Mission Motherland” is a lyrically and musically ambitious ode to panspermia: at nine minutes, it has its moments (some tempo changes keep things varied), but if you find the end of the album too much work, this is the one to skip. Weikath’s best song here might be the bluesy ballad “If I Knew”.

But then we get to the greatest thing album has to offer, Roland Grapow’s “Time of the Oath”. It has a grinding Zeppelin-esque set of riffs, a fantastically dense atmosphere, some spine-tingling choirs, and an electrifying vocal performance from Deris. “My sweetest memories…die in the cold!” Here’s where he conclusively demonstrates that he’s not just a spare tire until Michael Kiske 2.0 shows up, but Helloween’s new singer.

Helloween, for me, is not a band about speed and heaviness but about charm, and Time of the Oath ranks as one of their more charming releases. The songwriting, backed by Grapow and Weikath’s brittle Marshall crunch and Uli Kusch’s raw-sounding drums, has a deliberately and defiantly old-school flavor. The apocalypse described in the lyrics was sweeping over the industry like death, and here was Helloween, having the last laugh. The 90s were half-over, grunge was collapsing, and this defiantly 80s band was still here, playing power metal for all who wanted to hear it.

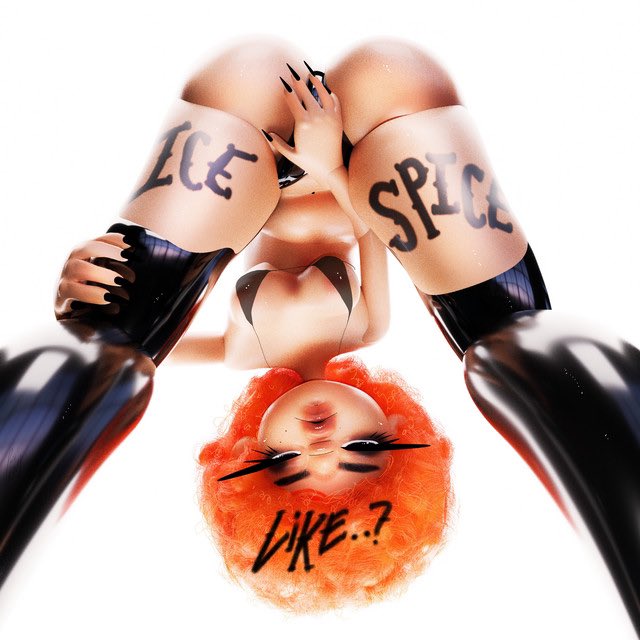

One thing I find fascinating about hip hop is that it lets you become the biggest musician in the world while releasing basically no music.

Isis Naija Gaston exploded in August 2022 with “Munch”, a 1:44 minute long track. Since then, a year has passed; an eternity in Social Media Time (read Wikipedia’s page of 2022 internet memes and marvel at how they already seem covered in the dust of ages—remember Morbius? The Liz Truss lettuce?). In those fourteen months, hip hop’s hottest new star has managed to release a single EP, titled Like..? It has a runtime of 13:08.

By way of comparison, from August 1968 to August 1969 James Brown released seven studio albums, plus a live album, totaling just under five hours of music. Is that unfair? Yes, but what’s staring me in the face here is that Ice Spice has become the “crown princess of Bronx drill” (Richdork Media’s words, not mine) off the back of less than half an hour of music.

She appears to be speedrunning (slowrunning?) the career of Cardi B, a woman described by Wikipedia as “one of the most commercially successful female rappers of her generation” and whose total recorded output over eight years consists of one album and three mixtapes. You can put a positive spin on this, or a negative spin. The positive: young rappers are at the cutting edge of a changing musical business, embracing a social media-driven world where “albums” and “physical media” are increasingly less relevant.

The negative spin is that maybe music isn’t very important to these people. That they view it as a hook to hang a brand on. Whatever value “Munch” has as a song—with its rapid shuffling hi-hats over deep smears of bass, and Ice’s cotton-batting soft voice—it has far more as a vehicle to get Ice out in the public eye, so we can notice and respond to her swagger, her style, her physicality. Some people want to be celebrity rappers. Others want to be celebrities who are rappers. There’s a big difference.

In How Brands Become Icons, marketing expert Douglas Holt lays out his theory that brands aren’t built on products, they’re built on spectacles. A successful musician doesn’t make good music (lots of people do that and nobody listens to it) but instead transforms their music into something bigger than itself: a splashy, attention-grabbing event. That’s what a lot of rappers amount to. Event merchants. They aspire to create as much hype as possible with as little music as possible. They are tiny pebbles that cause tsunami-like waves.

An “event” can be anything. It might be a hit song. It might also be a feud with another rapper, a shooting, a car accident, an overdose, or a death. Anything that bleeds, anything that makes it impossible to look away. The album cover of We Can’t Be Stopped by The Geto Boys shows rapper Bushwick Bill being wheeled out of hospital (an odd promotional choice: he’d been injured by a firearm while attempting to murder his girlfriend). In his review of 50 Cent’s The Massacre, Alexis Petridis noted that the album seemed to be banking on Fiddy’s reputation for violence. Your success in this game depends on how well you can deliver a drip-feed of exciting “events” to your audience without crossing a line and ending up dead.

And that’s how we get to the situation today: the average rapper’s Wikipedia page has a two line discography and then 3000 words on their Arrests/Legal Issues/Controversies/Sexual Assault Allegations. It’s not that they’re good boys who went down the wrong path. The wrong path was the point. That’s the product we’re paying for: shock and outrage. No beat goes as as hard as a bullet.

But here’s where Ice breaks the mould, because she’s mostly notable for not being controversial in any way. Raised in a comfortable middle-class family, she has no gang affiliations and no criminal record. Maybe this is another sign of hip hop becoming gentrified. More likely, the industry is sick of building up new talent only to have them die face-down in a puddle of Xanax vomit two years later.

Is Like..? any good? Glad you asked. Not really. It’s an EP of songs written around Tiktok and Spotify playlists. Each track is a tiny, self-contained manifesto on who Ice Spice is, demonstrating her strengths and flow. She’s getting paid! Guys are hitting up her ‘Gram! She’s from the Bronx! Each song is a miniature “intro” event, designed to be the first song you’ve ever heard by her.

The trouble is, after 5 or so tracks, we already know who Ice Spice is. We don’t need to meet her, over and over. Ice’s lyrics are limited. We see no signs that she’s a born storyteller, or has a perspective, a sense of humor, or any other quality that might be desirable in a rapper.

If this shit’s drill, I need Novocaine. The constant “Grrah’s!” and “Raggh!’s” get annoying. Nearly every song is produced in the same mannered, sterile way. Indeed, it’s probably smart that Ice hasn’t yet released an album. Her strengths (energy and steel-cool confidence) stop being interesting after a few minutes, and her weaknesses (her voice) become impossible to ignore. Ice’s intonation is petal-soft. As soon as the beat does anything other than “soft bass and hi-hats” she gets stomped to oblivion. The music has to stay kiddie wading pool shallow, or she drowns in it.

I’m old enough to remember arcades. They had games that seemed compulsively addictive, and always left you wanting more…but as soon as you bought them for home console, you were bored of them instantly. Ice Spice seems to be the rap version of that.

In the end, she just feels too well-behaved in the end. Like a rap robot, with some of the mannerisms of the real thing but none of the essence. Not that I like the essence, in any event. I’m probably just not a rap person.

(Also, Like..? sounds like a file designed to annoy Unix sysadmins. You wanna throw some asterisks and slashes in there, too? Maybe a “rm -rf /” while we’re in business?)