Enya’s fourth album finds her wealthy, successful, and comfortable. The music has started to suffer. The Memory of Trees is lavish…but it’s self-indulgent in places, and wants for the smallness and humbleness Enya had on her early releases.

Enya’s fourth album finds her wealthy, successful, and comfortable. The music has started to suffer. The Memory of Trees is lavish…but it’s self-indulgent in places, and wants for the smallness and humbleness Enya had on her early releases.

After the pleasant title track, we get “Anywhere Is”, which is catchy and enticing, but as unsatisfying as a cake that’s all icing. Enya’s voice utterly dominates the track. Enya used to sing over music, but now her singing is the music, with the instrumentation being some light percussion and orchestral stabs. The song sounds too samey. Where “I Want Tomorrow” and “Exile” took you on a journey, “Anywhere Is” takes you around in circles. Skip 10 seconds in or 30 seconds in or 1 minute in or 3 minutes in…same thing.

“Pax Deorum” is well-meant attempt at being creepy. It works about as well as “creepy” always does for Enya…not super well.

At “Athair Ar Neamh” the album finally gets out of cruise control mode. I really like this song. Enya sounds vulnerable and fragile, and Nicky Ryan’s production compliments the atmosphere. There’s still a “vocals > all” approach here but it works better than on other tracks. “From Where I Am” is a piano song that reminds a bit of the title track on Watermark.

From there the album goes back and forth between well-deserved classics and songs that sound pleasant and are easily forgotten. “Once You Had Gold” sounds great. “On My Way Home” comes from the same die as “Anywhere Is” but sounds a bit more varied and elaborate. “Tea House Moon” tickles the ears a bit with some strange melodies but doesn’t really stick with you. Another weird thing about modern Enya is that she doesn’t seem to be that great at writing instrumentals any more.

There’s not a lot of musical residue left over from The Celts. What a pity.

No more badass Vangelis-sounding tracks that mix classical music with futuristic synths. This is the album of piano, pad choirs, and Enya’s voice. No more songs like “Epona”, with wandering, lonely melodies that seem almost afraid to let you hear them. Enya now hews to a pop songwriting model worthy of Kara Dioguardi and Max Martin. This is the last Enya album I own a copy of, but I’ve listened to the later ones and they all seem to be like The Memory of Trees, but a bit worse. I wish Enya hadn’t decided that musical evolution means not adding things to her sound, but cutting things out of it.

Human cells die, and new cells regenerate in their place. After seven years, you are a completely new man. Clive Barker is Exhibit A of the hypothesis. The man who wrote great short stories like “Dread” has clearly been processed into skin flakes and loose hair and motes of dust, and in his place is…this man. Mister B Gone is rat shit. If Clive Barker can do no better than this, then I hope he never writes another book.

Human cells die, and new cells regenerate in their place. After seven years, you are a completely new man. Clive Barker is Exhibit A of the hypothesis. The man who wrote great short stories like “Dread” has clearly been processed into skin flakes and loose hair and motes of dust, and in his place is…this man. Mister B Gone is rat shit. If Clive Barker can do no better than this, then I hope he never writes another book.

It’s a written as the account of a demon who has escaped from hell via a fishing net (one of the perks of being a “fantasist” or whatever is being able to develop the plot via random spurts of Dadaist nonsense) and his adventures wandering the earth. Eventually he encounters Johannes Gutenberg, inventor of the printing press, which is the subject of a war between the forces of heaven and hell. One of Clive Barker’s recurrent ideas is that God and the Devil are not the embodiments of good and evil, but more along the lines of political rivals waging turf wars over corporeal fiefdoms.

The book doesn’t have a fourth wall. Jakobok the demon addresses the reader directly and urges him to burn the book, lest he damn his soul. The first time this happened I smiled. The second time made the corners of my mouth upturn by a zeptometer. The third time make me feel the inklings of fear. “He’s not going to do this through the whole book, is he?” By the tenth time I successfully trained my eyes to skip any paragraph containing the phrase “burn this book,” and I thereby greatly shortened my reading time.

What’s the point of such an annoying and persistent plot device? What’s the goal here, Barker? Is it to irritate the reader? I felt like I was reading a novelised version of that Paul Provenza/Penn Jillette Aristocrats movie, with a hundred comedians all telling the same joke, one after the other, and all of them acting like it’s fresh and new.

The story is worthless and uninteresting. Lots of events happen, but Clive Barker never brings any interest to any of them. It’s about demons and angels but I feel like I’m reading about sitcom characters. There are scenes in Hell that make it seem like Dogpatch with extra fire. Maybe that’s Mister B Gone’s biggest crime. It makes the supernatural seem dull and boring.

Clive Barker’s characterisation, never good, here reaches a new low. If you packed every character in Mister B Gone into an apple cart and pushed it off a cliff, I would be worried about the welfare of the apple cart.

Incredibly, this is Clive Barker’s first novel since 2001, discounting the Abarat books (which don’t sound interesting enough for me to want to read). Perhaps that’s the explanation. Maybe he’s more into screenplays and games and action figures these days. But shouldn’t a genius produce great work even when he half-asses things? They say Stephen King wrote The Running man in a single week…

In the meanwhile, someone please harvest the dust from Clive Barker’s house circa the Reagan presidency and put it to good use!

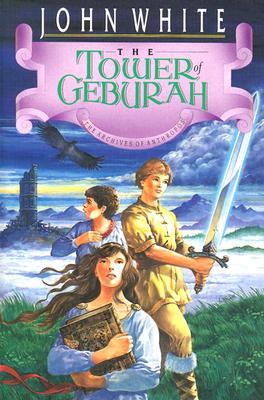

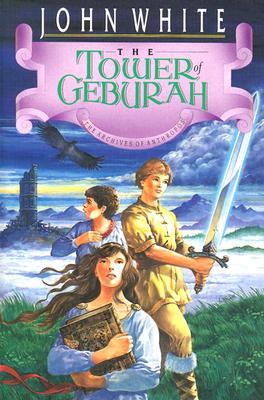

Some say Archives of Anthropos books are clones of the Narnia books. This is completely wrong. Author John White puts his own unique touch on the Narnia franchise: he makes it gayer and more boring.

Some say Archives of Anthropos books are clones of the Narnia books. This is completely wrong. Author John White puts his own unique touch on the Narnia franchise: he makes it gayer and more boring.

To explain, CS Lewis’s landmark series led to a boom industry of Christian books that involved children being whisked away to magical worlds. A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L Engle is a good example. It is a good book that compares well with Lewis’s work. The Tower of Geburah is the runt of the litter. On its own, it can perhaps mount a justification for its existence. But it led to a series of six Narnia ripoffs, which is really a bit much.

The story…? Mostly Narnia. I think he changed some names around. There’s a character called Mary who is exactly like Edmund. Actually I think she was from the second book. It’s been a while. The magical realm is called Anthropos, and it’s ruled by a king called Kardia. For Greek students, this means you are going on a magical journey to the nation “Man,” ruled by the goodly king “Heart.” Every time John White needs a name he just jacks it from some foreign language.

Many adults enjoy A Wrinkle in Time, but the only people who enjoy The Tower of Geburah are people who read it as kids. I’m not one to take away from anyone’s formative memories…but damn it, you were a child. You spent your days jamming crayons and glue into your mouth. We don’t let children drive, we don’t let children drink, and we don’t let children vote. Why do you think your child opinions on literature are worth a shit?

My advice is to re-read The Tower of Geburah with the greatest of caution. You first experienced it through the warped perspective of childhood. You might think adulthood would give you a greater appreciation of this animal, but in this case you’re just more likely to notice the faux fur.

Enya’s fourth album finds her wealthy, successful, and comfortable. The music has started to suffer. The Memory of Trees is lavish…but it’s self-indulgent in places, and wants for the smallness and humbleness Enya had on her early releases.

Enya’s fourth album finds her wealthy, successful, and comfortable. The music has started to suffer. The Memory of Trees is lavish…but it’s self-indulgent in places, and wants for the smallness and humbleness Enya had on her early releases.