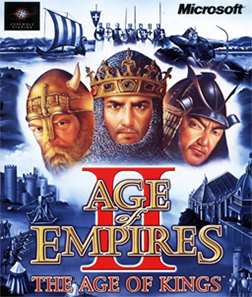

In 1999, Ensemble Studios made a game that changed the world.

In 1999, Ensemble Studios made a game that changed the world.

Trivially, every game changes the world. Even a game programmed and left unreleased in a military bunker changes the world, insofar as there is now less free energy to make more games. But Age of Empires II did more than accelerate the universe’s incoming heat death. It gave us cause to regret it.

You don’t hear much about real-time strategy any more. I experienced the history of the genre in reverse, starting from AoE2 and working backwards through all the classics. It was like being a gaming Benjamin Button. Everything just getting crappier and crappier. Starcraft only lets you select 12 units at a time. Total Annihilation has craptastic pathfinding. Age of Empires I has a 50 unit limit and no production queuing. Warcraft II only lets you select 9 units at a time. Command and Conquer has clunky controls and rat-fecal AI. Warcraft I only lets you select 4 units at a time. Dune II only lets you select ONE unit at a time. It felt like the joke where a Jewish kid asks for five dollars, and his dad goes “Four dollars? What the hell do you want three dollars for?”

Curiously, I don’t experience the reverse experience when I play games made after Age of Empires II. There’s no sense of “wow, this is much better”. I suspect Age of Empires II was about as good as the genre ever got.

The game’s tons of fun. It takes the first Age of Empires’ “Warcraft but now you can pretend to mum and dad you’re learning about history” hook and takes it into the middle ages. Can Frankish paladins overcome Persian war elephants? Are Mongolian cavalry archers a match for Turkish artillery? Will your prepubescent opponent question your sexual orientation and your mother’s virtue? Learn these answers and more.

As a new player, your first instinct will be to haul ass to the single-player mode. General surgeon’s warning: AoE2’s singleplayer is slow, boring, repetitive, and teaches you bad habits. Spent as little time there as possible.

Play multiplayer instead. This game’s multiplayer is great, and at a certain skill level, transcends great and becomes godlike. There’s so much artistry, so much finesse, the axle of a 1vs1 turning on such pivots as a forward tower losing 10hp to an attacking villager, or someone having a position that’s slightly downhill. The game’s surprisingly almost balanced between civilisations and unit types, and various fan mods and patches scratch the word “almost” away from that description. 1vs1s are like a fencing match, full of lightning-fast action and counteraction. 4vs4s change the dynamic to something huge and Game of Thrones-esque. It almost feels like a totally different game.

But let’s be honest, these games are dark triad simulators.

Age of Empires II puts you in control of many putative human lives, but not in a way where they emotionally effect you. They’re so far away on the screen that your brain just registers them as “game pieces”. There’s no “grieving widow” meter in this game. Everyone’s just kind of cannon fodder. How careful you are in sacrificing men depends entirely on how much food, gold, and wood you have to make new ones.

In Grand Theft Auto, human beings behave like human beings. Even a primitive game like Doom puts you up close and personal to the monsters, so you can see them react in pain. But real time strategy games seem like how a sociopath views the world. I know I lasted about a week on my first Age of Empires II forum before I stopped calling my soldiers “men” and started calling them “units” like everyone else.

Potentially disturbing insights into your psych aside, Age of Empires II is an aesthetically nice game. Starcraft and Total Annihilation are set in dismal hellscapes. Age of Empires II takes place in landscapes as pretty as a travel brochure. Everything has a nice heft and sense of scale – castles tower above the landscape, galleons seem appropriately big. The game is visceral enough to break through the sociopath filter every now and then, although not always intentionally. You can control sheep, and send them on long journeys across the map. Demonic possession? And slain bodies swiftly decay into skeletons – often while other soldiers are still fighting around them. Disturbing, as if everyone is caught in a time-lapse vortex.

These days I see a bored programmer going “who gives a fuck, nobody will care about that” and punching out for the day. But back then, these little flaws in the reality of the game were kind of creepy. They seemed like they must have been planned. That’s one of the things about being a kid. Everything seems planned.

I first played this game as a child, and although I commanded a kingdom, mentally I was probably more like those villagers, who trustingly obey orders even when you make them walk in circles, or into enemy fire. These guys don’t realise that sometimes the ship’s captain is an idiot, or that sometimes the ship has a broken rudder.

Anyway, what I’m saying is that this game is pretty good.

“So this is how liberty dies,” says Deanna Troy, a character in Rod Serling’s famed sci-fi series Babylon 5. “With thunderous applause.” Submission is set in near-future France, where an Islamic party of Wahhabist mien has ascended to power. Various European features like women’s rights are being clawed back, and the country is beginning to de-Westernise.

“So this is how liberty dies,” says Deanna Troy, a character in Rod Serling’s famed sci-fi series Babylon 5. “With thunderous applause.” Submission is set in near-future France, where an Islamic party of Wahhabist mien has ascended to power. Various European features like women’s rights are being clawed back, and the country is beginning to de-Westernise.

The book is called “Submission”, not “Rebellion”. Expected notes of defiance or insurrection aren’t found here. Nobody hides a dagger inside a niqab or hijab. The heart of the matter is this: Michel Houellebecq doesn’t think Western culture is worth saving. His take on an Islamist takeover of France is something like “good, you deserve it.”

The main character is incidental: a middle-aged literature professor who lays pipe in various female students (apparently Houellebecq wasn’t very successful with the fairer sex when he was young. He’s certainly making up for lost time in the pages of his books). Blearily, as if through a panopticon, we see the political stormclouds rattling France. In order to obstruct a right-wing takeover, France’s Socialist party is allying with the Muslim Brotherhood, turning them from a wedge party to an actual force. Soon, Francois sees the future: Islamist Mohammed Ben-Abbes will be president of France.

Scenes of Francois’s daily life are deliberately flat and empty, like slashed tyres. Things like microwaving dinner end up being little manifestos of ennui. Houellebecq hits you hard with pointlessness of it all, and although he almost superglues his tongue inside his cheek (one of the places Francois stays is the site of the Battle of Tours in 732 ad), it’s hard to call this book satire, unless it’s satire with an incredibly broad target: like western civilization or perhaps sentient life as we know it.

The book came out on the 7th of January. On the same day, two Al-Qaeda shooters blessed and culturally enriched eleven magazine publishers in France. For all Houellebecq’s contempt for Islam (“the stupidest religion”, as he says), it’s never dealt with him as it has with Charlie Hebdo, or even Salman Rushdie. Indeed, it’s mostly his fellow westerners that have caused him problems, charging him with hate crimes and forcing him into exile and all the rest of that business.

On one hand, Islam occupies a central role in Submission. On the other hand, it’s hardly in the book at all. French decadence is Houellebecq’s real target. Islam, as he sees it, is just a memetic predator in a world full of memetic predators – it’s the responsibility of guards to stay at their posts and keep the predators out. And France has found her guards asleep at their posts.

After Charlie Hebdo, I assume people rushed out to buy Submission, expecting solidarity and French pride and saber-rattling, and were a little surprised by what they got.

It’s not that Houellebecq’s writing is dark. Lots of writers are dark. The thing is that you never know where you stand with Houellebecq, or are sure of what he’s truly saying. I don’t mean that in an obscurantist postmodern sense. I mean it in the sense of Hitler’s quote “You will never learn what I am thinking. And those who boast most loudly that they know my thought, to such people I lie even more.” Houellebecq’s work is full of crypto-Marxist and crypto-reactionary asides and allusions, like squid ink to conceal his true views. What, finally, is Houellebecq’s stance? That France needs to recover its spine? That’s too easy.

His mind is a black box, and so is this book.. In the end, the only thing I can draw from the soil of Submission is that France can probably no longer with saved. He’s a bit like Martin Amis, who was born in the UK but has permanently relocated to the US. Sometimes you can take the jungle out of the boy.

How many tell-all books about KISS do we need? Here’s everything you need to know: Gene and Paul = high-functioning assholes, Peter and Ace = low-functioning assholes. This dynamic anticipates and explains every twist and turn of the KISS story in the past 40 years.

How many tell-all books about KISS do we need? Here’s everything you need to know: Gene and Paul = high-functioning assholes, Peter and Ace = low-functioning assholes. This dynamic anticipates and explains every twist and turn of the KISS story in the past 40 years.

Drilling a bit deeper, you could say that Peter is deeply insecure and has a Napoleon complex, while Ace was/is a skinsuit piloted by various drug monkeys that doesn’t care about anything much except getting high. You could say Paul is deeply insecure and holds fantasies of being an “icon” (a rock god, a sex symbol, whatever), while Gene Simmons is basically after “fuck you” money. So in a sense, you could draw a dividing line orthogonal to the first one. Peter and Paul’s motives are complex. Gene and Ace motives are simple.

Despite his simplicity, Simmons is the most intriguing part of KISS. The man is so naked and undisguised in his greed that he becomes fascinating, and even a bit likable in a perverse way. It’s as if Donald Trump played rock and roll.

This is the worst album I’ve heard all years. It’s the worst album I’ve heard in several years. It is unmarred by a single listenable cut. It’s not even a failure, it’s just…anti-musical. Like something that was never even intended to be good.

What do you think of bands like the Pretty Reckless? If you’re like me, your answer is “not much”, but I wouldn’t dispute that they’re at least trying to write music that you’ll enjoy. There is no way on earth you’re supposed to enjoy Asshole. It was made by a mind filled with contempt and loathing for his audience, someone who wishes he could just reach into your wallet and take money but is limited by law to the next nearest thing. It’s like having Gene Simmons flip you the bird for 40 minutes.

Horrible performances of horrible songs, that’s what’s on offer here. Gene’s voice is shot, he sounds like a 60 year old man doing karaoke. “Sweet and Dirty Love” and “Weapons of Mass Destruction” sound like what old people think heavy metal is – noise and no hooks. The title track features the couplet “you’ve got a personality / Just like a bucket full of pee”…yes, that’s what we’re working with here. “Carnival of Souls” has an unbelievably terrible chorus.

Then there’s a cover of “Firestarter”, a perplexing choice that is ruined by Gene’s flat “your call is important to us” vocal delivery. You know how they used to joke that Arnold Schwarzenegger has an acting range stretching from A almost to B? Gene Simmons is the same, but remove the “acting” part.

And are you ready for the horrible news? The terrifying “Soylent Green is People” revelation?

These are the album’s good songs.

The rest of this CD is packed with terrifying and near-apocalyptic crap that sounds like adult contemporary/soft RnB music. It’s not hard rock, it’s not even soft rock, it’s basically Boyz 2 Men with a bad singer. I couldn’t believe it. I still can’t. It feels like this must be a false memory implanted by the government. Why would the bassist of KISS release an album where at least 50% of the music sounds like a gentle spanish. Then I hear the gentle Spanish guitars and female backup vocals of “If I Had a Gun”, and I realise the nightmare is made of flesh, not dream matter.

Did you know Gene Simmons has a sex tape? Yes, I’ve seen it. No, he doesn’t look any better in his birthday suit. This album sounds like the kind of thing that could have scored it.

In 1999, Ensemble Studios made a game that changed the world.

In 1999, Ensemble Studios made a game that changed the world.