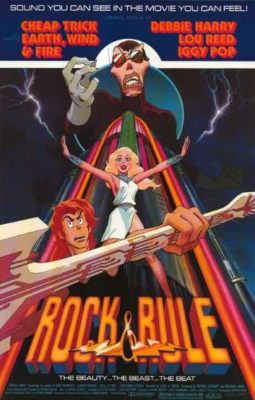

This is a 1983 Canadian post-apocalyptic science fiction fantasy musical adult* cyberpunk neo-noir animated furry i hope i die

The plot is incidental (and embarrassing); cartoon mice save the world through the power of rock. It’s based on a 1978 Nelvana TV special called The Devil and Daniel Mouse, but updated to be edgy and dark and very, very serious. The songs are pretty thin, and guitars are wielded more often as weapons than as instruments.

But there are good moments, too. Some nice animation, and occasionally great character design. I say “occasionally” because it partakes in animation’s most onerous trend: Humans with Dog Noses. Who started the HWDN craze? Carl Banks? The Beagle Boys were obviously cartoony, but here we have straight-up humans with dog noses. It looks ridiculous, and immediately deep-sixes the edgy, dark, serious premise.

Dog noses are the first of many questionable artistic choices. The supporting characters are drawn like funny animals, but the lead characters are drawn realistically. They don’t seem to exist in the same world, and when whenever a lead and a support stands together the sharp disjunct between the two styles is all you can focus on.

My favorite part of the movie is everyone’s favorite part: the villain Mok. He steals the show with one of the most innovative character designs I’ve ever seen in an animated movie: a pastiche of Mick Jagger, Lou Reed, and Thin White Duke-era David Bowie. His face is an unimaginably complex manifold of vertices and angles, blending the feminine and masculine (and canine, but I’ve made my point), and the animators deserve kudos for keeping his ridiculousness on model. The movie suffers greatly whenever Mok’s not on screen, although there are fun computer-generated visuals and Debbie Harry does the best job she can.

The story in brief and in full: Mok (“the only Ohmtown rocker to go gold, platinum, and plutonium in one day!”) is seeing his commercial success wane, and hatches a plan to summon a demon from hell so he can…I dunno. I seriously have no idea what he’s trying to do, but we never understood what David Bowie was trying to do in real life, so there you go.

He kidnaps the female singer from a shitty glam rock band, because only her voice can complete the satanic ritual. Her dislikeable male co-singer has to rescue her along with some bumbling comic relief characters, who are more like comic constipation. Mostly, the movie succeeds in making you groan and cringe, such as when we find out they’re playing at Carnage Hall in Nuke York.

Bootlegs credit the film to Ralph Bakshi, which is false, yet also true, because this sort of movie probably wouldn’t exist without him. The success of Wizards and Fritz the Cat ushered in a few brief years when studios gave a bit of rope to animated films that weren’t obviously for children.

The rope had apparently played out by 1983, and Rock & Rule feels tampered with. The Gibsonian cyberpunk atmosphere is leavened with moments of wacky slapstick that could have been spliced in from Goof Troop (they couldn’t, for chronological reasons, but the vibe is similar). In particular, Mok’s henchmen ride around on rollerskates, which might have been an effort to save money on animation. When your characters are on wheels, it doesn’t matter if they slide around on the frame.

If a studio meddled with Rock & Rule, this is understandable. The film is confused and hard to market, and I’m still not sure who it was for. But it didn’t make any money even with all the commercial compromises, so why did they even try? Go for broke on your crazy post apocalyptic rock musical furry whatever! I’m reminded of this exchange from Karate Kid:

“I’d get killed if I go down there!”

“Get killed anyway.”

* (“Adult” means two fully-clothed characters feeling each other up, implied drug use, a Satanic pentagram, some intense imagery, and one character calling another “dick nose”, which if true would still be an improvement over dog noses.)

No Comments »

I don’t know if the third Quake is a better game than I and II, but it’s certainly less of a game. They cut away any story mode, focusing it like a laser on its deathmatch experience. You run in circles, trying to kill enemies more times than they kill you. The sarcastic way people described Doom and Quake is now a literal reality.

The result is a first person shooter of incredible purity. Playing Quake III Arena is like breathing pure oxygen – liberating, and destructive to your health. As soon as a stage loads, your mind enters a trance state, and your body falls away. Only three things remain: a left hand on the WASD keys, a right hand clicking the mouse, and an eye orchestrating the violence. The circuit sparks and crackles, the connections fusing together, and when the match ends, it takes a few seconds for the hands-eye unity to remember it has a body.

The game was meant to be played with other people. It has a single player mode, but it’s not a good one and you sense the game is laughing at you for picking it. You play against “bots”, which aren’t smart but are difficult in an abusive fashion. Turning up the difficulty means they gain split-second reflexes and superhuman accuracy – they simply never miss with the railgun, which isn’t fun.

As with past Quake games, there’s a game-inside-the-game, and mastery of competitive online play requires exploiting oddities in the code like rocketjumping (surfing the blast of an exploding rocket), plasma climbing (scaling walls with blowback from the plasma cannon), circle-jumping (pirouetting to add massive velocity to your next jump), and more. The developers would probably spit out their Adderall-laced coffee if they saw what modern players do with Quake III.

A game like this isn’t about content, but about balance. While Doom’s juice came from “yay, cool weapon” and “yay, cool map”, Quake III’s design requires an analytical approach: “are the weapons equally strong, or does one dominate? Are the maps laid out in a way that leads to fair gameplay, or can you just camp a spawn spot and fight off all comers?” Single player is about indulging orgiastic power fantasies, while multiplayer is about fair play and rules. It’s hard to get both right with the same game engine, and maybe it was for the best to ditch a story mode.

The graphics were great, almost to the point of undercutting the game’s minimalist ethos. This game reduced your Riva TNT to sludge. But the lighting, shadows, and all looked very good for the time, with the only competitor being Unreal Tournament.

Thomas Aquinas once said “I fear the man of a single book.” The idea is that you can be unstoppable by doing one thing very well, and Quake III Arena does indeed do one thing very well. “It’s just mindless violence!” – some developers tried to dignify their games away from that, but id Software was apparently taking notes for their next design document.

No Comments »

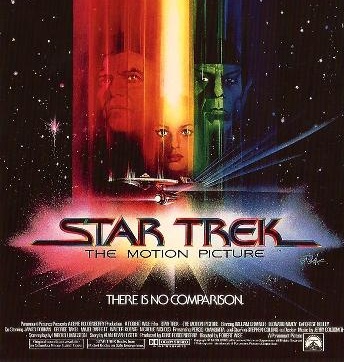

A cloud of iridescent energy slides across the galaxy, destroying all in its path. As it approaches Earth, James Tiberius Kirk bullies Starfleet into giving him control of the Enterprise, one last time. Incidentally, did James go through boot camp? Hard to imagine a guy called Tiberius doing push-ups and getting yelled at by R Lee Ermey. When your name is Tiberius they probably promote you straight to captain.

Star Trek: The Motion Picture is great, if in a troubled way. It’s like a titan, ready to collapse under its own weight. The philosophical method of”structuralism” seeks to understand things through their relationship to other things (eg, a ship’s mast can only exist if there are sails and a hull, otherwise it’s just a wooden pole), and Star Trek: The Bowel Motion Picture can only be understood in light of its own difficult creation.

Let’s start at the beginning. Once, there was a television show called Star Trek. It was both unpopular and cancelled. Half a century later, it’s the defining science fiction series of the silver screen.

How did this reappraisal happen? The same way the Velvet Underground became popular: they sold a few thousand copies, and all of those people started a band. Star Trek’s audience was tiny, but it consisted was of scientists, writers, activists, and other people who wielded a disproportionate impact on the tastes of 1970s America. Their beloved show was dumpstered, but these people were too aggressive to let it be forgotten. They rang phones. They wrote letters. The megaphone-wielding minority soon had the show firmly established in syndication, and a slow critical reassessment began: this thing is actually really good.

Star Trek was often campy, but never cynical or insulting. The writing was often broad, but was never boring. Gene Roddenberry was brilliant at directing attention away from the show’s weaknesses (its budget) and toward its strengths (screenwriting, and Shatner, Nimoy, and Kelley’s acting).

With voltage gathering for a continuation for the series, Paramount Pictures and Roddenberry began working on a pilot. It was a mess. Writers were commissioned, and their scripts rejected. Actors were hired, and their parts written out. Sets were built, then stripped down. I’m stunned that Burbank’s air was declared safe to breathe after so much burnt cash.

Finally, just weeks before shooting was due to start, Close Encounters of the Third Kind hit the box office like a wrecking ball. The prevailing cultural winds now favored movies instead of TV. Paramount panicked and changed their plans: when Star Trek returned, it wouldn’t be as a TV series but a motion picture.

This spelled disaster for Roddenberry. There was not enough time. The production was thrown into chaos, and the planned pilot was hastily refitted into a two hour movie, with a script written as they went along.

The result is a odd experience, stretched and deformed. It’s a Star Trek television episode viewed through a funhouse mirror: you can recognise the shape, but it’s 50% wider than it needs to be. The opening sequence is thrilling: three Klingon ships are evaporated in an impressive visual effects sequence. Exciting. Star Trek was back, now with a budget!

But then we get an hour of “character development”, meaning James T Kirk butts heads against the Enterprise’s dull new captain, while the plot spins its wheels and goes nowhere. We also meet a female alien called Ilya, who talks and talks and talks and sets records for uninspired character design. I’ll buy that a man with pointy ears might be an alien. Ilya’s literally just a woman with a shaven head. You can find plenty of aliens like her at the local slam poetry meet.

The film’s strengths are its visuals: something that was never a strong point with the original show. Douglas Trumbull and a young John Dykstra slather the frame with luminous rainbow hues (Trumbull previously worked on 2001: A Space Odyssey, and the film owes a lot visually to that one, including a “smash cut from rainbow fluorescence to stark white” moment that matches 2001’s Star Gate sequence). The more practical effects are beefed up as well. A tiny Burbank sound stage is make to look like an absolutely massive cargo bay thanks to forced perspective (those tiny figures in the background? Children.) I think this is the first time we’ve seen a Star Trek space battle where both ships are composited into the same frame (as opposed to a shot/reverse shot of the Enterprise firing and another ship blowing up.)

The story is a bit perfunctory, and the imagery seems to transcend the characters until they’re reduced to spectators, gaping at the wonders of the cosmos. Maybe that’s the attitude Star Trek always tried to evoke. More likely, it’s a disguise for the fact that this was supposed to be a TV pilot, and they just plain didn’t have enough story.

I once saw a film called American Movie, about a pair of young indie filmmakers. One of them has a memorable monologue: “There’s no excuses, Paul. No one has ever, ever paid admission to see an excuse. No one has ever faced a black screen that says: ‘Well, if we had these set of circumstances, we would’ve shot this scene… so please forgive us and use your imagination.’ I’ve been to the movies hundreds of times. That’s never occurred.”

He should have seen Star Trek: TMP. It has excuses. Many of the visual effects (although stunning) don’t serve a purpose beyond “we don’t have any actual story to put here, enjoy these flashing abstract colors”. Big chunks of the film are a laser light show in space, intercut with shots of the crew looking awed. For a while, you share their awe. But then it feels like it’s time for something to happen.

Calling a movie “The Motion Picture” sounds either presumptuous of horribly underconfident: you’re either suggesting that it will be the definitive one, or the only one. In the case of ST:TMP, I can’t even call it A Motion Picture, as it’s been recut and re-released many times. The film is now legion, I’m not sure if the original version is exists today in a purchasable form. Although it’s a different sort of Star Trek, I enjoyed it a lot.

(It’s worth noting that Orson Welles voiced the cinematic trailers for this movie. One year later, he’d be voicing Manowar songs, and commercials for frozen peas.)

No Comments »