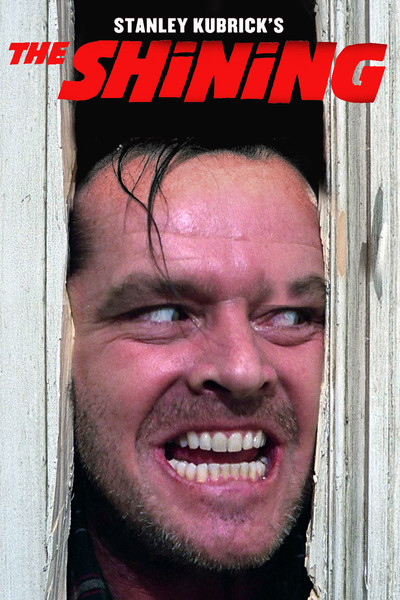

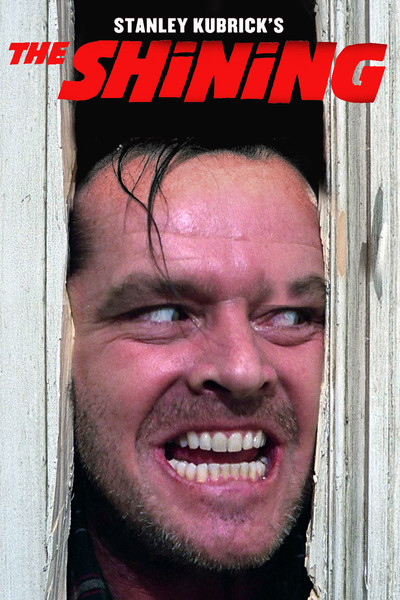

Stanley Kubrick was a consummate perfectionist. Actress Shelly Duvall remembers the shooting of The Shining as 200 days of fake crying and swinging a bat, over and over, sometimes for dozens of takes. There’s a Hollywood joke about how directors get lazier as the day goes on. “At 7:00am, you’re shooting Citizen Kane. At 7:00pm, you’re shooting Plan 9 From Outer Space.” Stanley Kubrick wanted Citizen Kane at 7:00am, Citizen Kane at 7:00pm, and if he could wrangle it, Citizen Kane during his cast’s lunch break.

Stanley Kubrick was a consummate perfectionist. Actress Shelly Duvall remembers the shooting of The Shining as 200 days of fake crying and swinging a bat, over and over, sometimes for dozens of takes. There’s a Hollywood joke about how directors get lazier as the day goes on. “At 7:00am, you’re shooting Citizen Kane. At 7:00pm, you’re shooting Plan 9 From Outer Space.” Stanley Kubrick wanted Citizen Kane at 7:00am, Citizen Kane at 7:00pm, and if he could wrangle it, Citizen Kane during his cast’s lunch break.

This obsessive approach actually made his films less perfect, as it increased the odds of a continuity error between shots. Kubrick’s films are a target the size of a barn door for the forces of entropy, and indeed, the final cut of the Shining has a lot of goofs. Furniture mysteriously moves between shots. Danny’s sandwich has different bite marks.

I think Kubrick must have been aware of this, because The Shining also contains extremely big and easily fixed mistakes, ones that a perfectionist surely would have noticed. At the start of the film, the caretaker who murders his family is named Charles Grady. But when Jack Torrance meets the caretaker (or his ghost), he introduces himself as Delbert Grady. The climax of the movie involves a chase through a hedge maze, but, but in the opening aerial shots (where we see the entire Overlook Hotel) there is no hedge maze on the estate.

These blunders are so big and showy that they seem intentional. They’re so clearly part of the movie that one attaches thematic significance to them (Jack’s perception is unreliable, the hotel is not as it seems, etc), and maybe Kubrick was hoping we’d also attach thematic significance to the smaller ones, too. After all, a mistake is only a mistake when you admit it. Everyone knows that when you mess up performing a martial art kata, you don’t hastily correct. You make it look like you meant to do that.

If this was Kubrick’s strategy, it worked. Mssage boards are full of thematic analysis of the different bite marks in the sandwich, and so forth. Nobody will believe that he was actually capable of making a mistake.

Stephen King famously didn’t like this adaptation. Kubrick probably couldn’t have adapted any of his works to his satisfaction, except maybe for Christine, which is about a car. Kubrick’s movies are very cold, and although sometimes full of human energy, they usually don’t have a human heart. Jack hacking through a bathroom door is scary the way a wind-up machine doing the same thing is scary. King’s novel invites us deep into Jack’s psyche, while Kubrick’s movie turns him into another scary thing in a house full of scary things.

Were these intentional stylistic touches? Or where they deficiencies in Kubrick’s storytelling abilities? Because of Kubrick’s tactics, I’m not sure. At a high level, it’s difficult to tell a feature from a bug.

I feel the same way about the changes to the story’s lead. In the book, Jack Torrance is a nice guy with a monkey on his back. In the film, he’s a terrifying alien almost from the beginning. His suit doesn’t fit. He pounds the keys on a typewriter as if it’s a boxing match. When his new employer asks if his wife is comfortable staying at a hotel with such a gruesome history, he replies with something like “she’s a confirmed ghost story and horror film addict!”, hitting a jarring combination of weird and socially awkward. Every time he smiles, it’s an uncertain smile, as if the reptile inside is worried about tearing the human skinsuit.

Almost all of the film still holds up. It cuts out most of King’s self-indulgent touches (the living hedge maze animals, the jar of wasps), leaving a story that’s very slow while never dragging. You feel the passage of time, and the alienation from the outside world.

I think he damaged Shelly Duvall’s sanity, though. The woman just isn’t right.

No Comments »

What happened here?

What happened here?

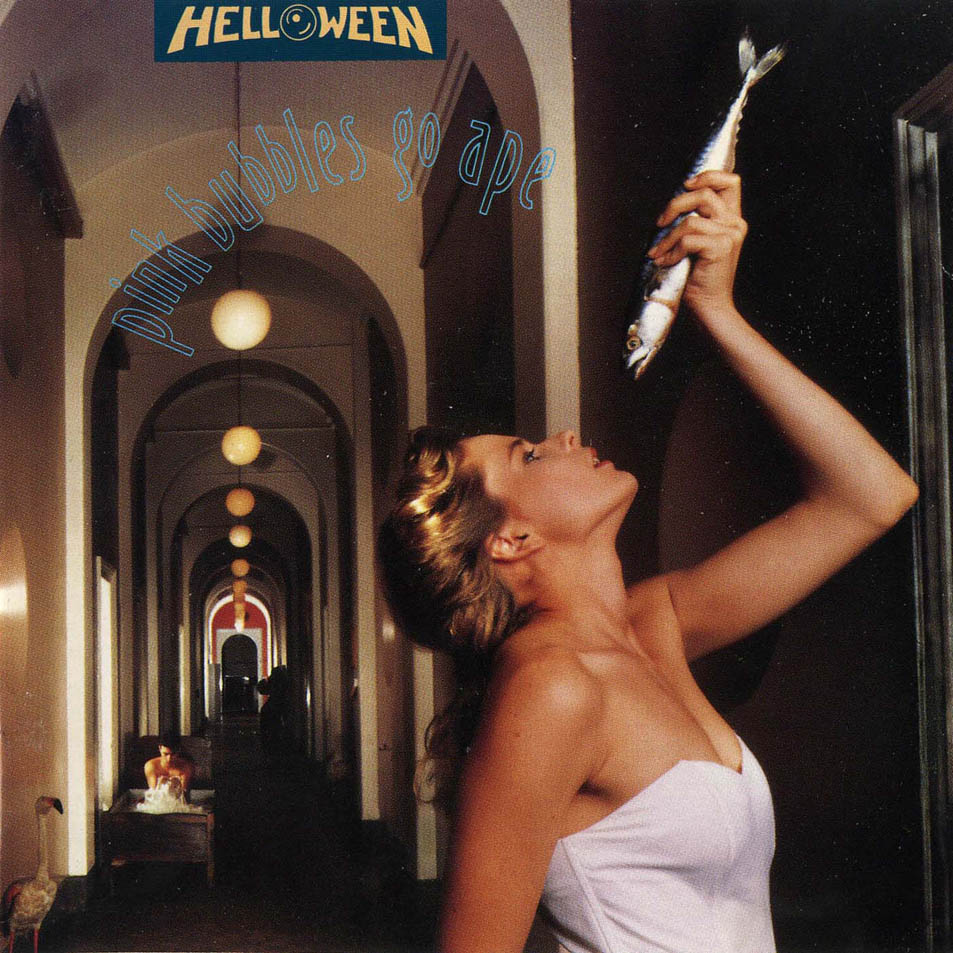

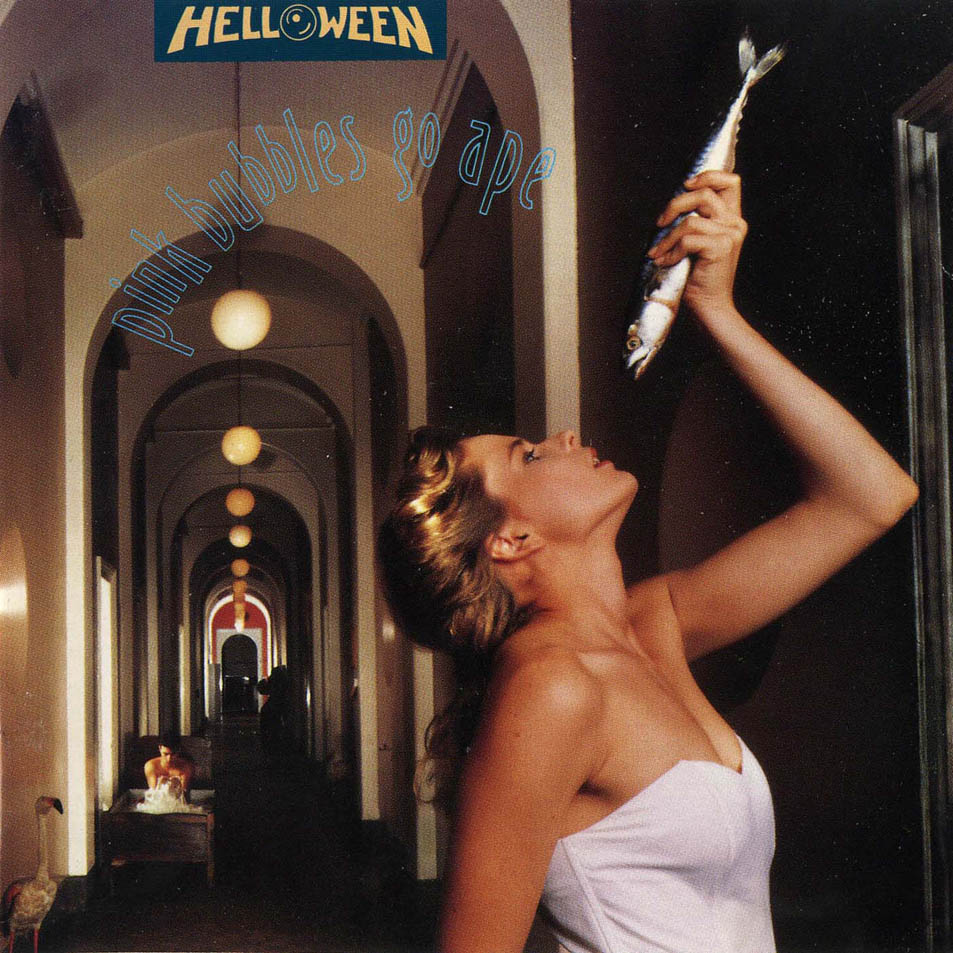

Helloween’s fourth album is stupid and bad, and it’s stupid and bad in a way that bands are normally immune to. Pink Bubbles Go Ape would have made sense coming from a solo artist. All artists have THAT period, where they snort a rail of coke laced with rat droppings and make a concept album about socks disappearing inside the lint dryer. But how the fuck did five members all agree to sign off on this inanity?

To recap, Helloween were on an incredible hot streak through 1985-89. Walls of Jericho and both of the Keeper albums (notice that I make no mention of a third) wrote the book on Teutonic power metal. After touring with Exodus and Anthrax, and getting airplay on Headbanger’s Ball, they finally seemed on the verge of a big break.

Then principle songwriter Kai Hansen left the band. His final composition on a Helloween disc, “I Want Out”, was apparently less a catchy tune than a dire prognostic. Immediately, the band went into a tailspin, with drummer Ingo Swichtenberg’s schizophrenia becoming worse and vocalist Michael Kiske now harboring delusions of reinventing the band as a pop group.

Three years later, we got this, and the band’s chances at becoming a mainstream metal act ended in a fit of pure absurdity. It’s one thing to shoot yourself in the head. Helloween managed to shoot itself with one of those joke store pistols with a spring-loaded *BANG* flag.

The album is either hard rock music that isn’t very good, or comedic lyrics that aren’t very funny, and usually both at the same time. Almost none of it sounds like power metal. “Kids of the Century” makes an effort at rocking hard, before confessing partway through “yeah, I got nothin'”. “Number One” is a Weikath song from the early 80s. It’s no mystery why it never appeared on a past Helloween, but why it’s on this one is mystery aplenty. “Goin’ Home” and “Heavy Metal Hamsters” are like special-needs glam rock, if such a thing existed. I’m imagining huge teased 80s hair, hidden beneath a SPED helmet.

In a final surrealistic touch, the only songs that sound like old Helloween (“Somebody’s Crying” and “The Chance”) were penned by new guitarist Roland Grapow. Both of these songs are great, particularly the second one, which has lots of soaring guitar harmonies and a dog-whistle high note from Kiske. Grapow was a thirty year old car mechanic, drafted to fill the gap left by Hansen’s department, and “The Chance” reflects the optimism at such a stroke of luck. Unfortunately, Helloween was and is a dysfunctional band (even without Kiske), and in ten years he’d probably relate more to “I Want Out.”

“Mankind” wastes a great Queensryche atmosphere with a goofy chorus, and the final ballad “Your Turn” is saccharine gloop. It’s nearly as bad as “A Tale That Wasn’t Right”. Put this in your car’s fuel tank and your ride would never work again.

What’s the French expression? Folie à deux? A bunch of people suddenly going mad (or ape, as the case may be?) It basically put a spoke in the band’s wheel, and set off events that would leave most of Helloween’s lineup getting fired or dead. It’s a tragedy, masked as a comedy.

No Comments »

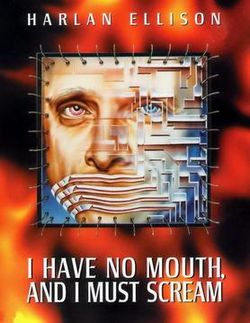

Released in 1995, just as the adventure game genre was falling off a cliff, I Have No Mouth Et Cetera captures the industry in its final nihilistic burn-it-to-the-ground moment, where game developers were flailing around and trying every crazy idea to win back their audience from Myst. A lot of fascinating experiments emerged from this period, including this adaptation of a Harlan Ellison short story.

Released in 1995, just as the adventure game genre was falling off a cliff, I Have No Mouth Et Cetera captures the industry in its final nihilistic burn-it-to-the-ground moment, where game developers were flailing around and trying every crazy idea to win back their audience from Myst. A lot of fascinating experiments emerged from this period, including this adaptation of a Harlan Ellison short story.

The plot starts out similar: fuelled by Cold War hysteria, the human race engineered its own coffin. 109 years in the future, a godlike supercomputer called AM now controls the earth, having utterly destroyed the human superpowers that thought it would protect them.

AM has kept the last five humans alive for more than a century, torturing them in all sorts of physical and psychological ways. But at last it has grown bored, and has engaged the captive humans in one final game: they must survive a scenario constructed from their own minds, mortared by their own repressed traumas.

Gorrister is a suicidal loner who resents women. Ellen relives a violent rape whenever she sees the color yellow. Benny is a perennially hapless loser who has been altered to look like a gorilla. Ted is a paranoid lunatic who is “so twitchy he could make poison ivy nervous.” Nimdok is a Nazi scientist who assisted Dr Mengele in the Holocaust.

Using a point and click interface you explore each of these characters’ minds. Whether you can “win” is unclear, even at the end. AM has complete control over all of these characters, and there’s no reason that it should tell the characters the truth about their past lives or current predicament.

At its best, IHNMAIMS is a fascinating and memorable experience, and it’s often at its best. It removes most of the comical aspects of Ellison’s story (like the “we have canned food but no can opener” gag), and adds far more depth of character. The story was about five interchangable nobodies surviving a maniac computer. The game centers its focus on the characters, and explores their pain. Rather than a telescope looking outwards, it’s an MRI looking inwards.

Unfortunately, the adventure game genre died for good reasons, and IHNMAIMS showcases many of them.

Pixel hunts. “Puzzles” that amount to trying random combinations of items and actions. A lack of direction that means you cannot solve the game in any logical way. The game conjurs a dreamlike atmosphere, which helps the narrative but kills any sense of gameplay. Most of IHNMAIMS consists of wandering around in a daze, clicking on things.

Here’s a good example: you try to cross a bridge, but it requires a passcode. Only Nimdok knows the passcode, meaning there’s an 80% chance you’ll have selected a character that cannot get past that point. You’re stuck. There’s no way to figure out the passcode on your own. You either made the correct choice previously in the game (without knowing it), or you haven’t.

The interface is unintuitive. There’s ample opportunities to “strand” yourself, with no way forward and no way back (again, you won’t know this in advance, so your save is now probably useless), and the puzzles are usually completely unclear as to whether you’ve solved them or not. That’s my criticism of IHNMAIMS: there’s never any goddamn feedback when you do something. Are you going the right way? The wrong way?

Grognards spit upon The 7th Guest as not being a true adventure game, but in a way, it got something right. The puzzles were self contained, and had rules that you could follow. You’d beat one, and move on to the next one. Sometimes those puzzles were hard, but you could always understand them. You weren’t wandering around trying to guess what the developers wanted you to do.

So you have a fascinating layer of content, but it’s stuck inside a frequently clunky and frustrating adventure game. Unfortunately, stories improve games far more than games improve stories, and IHNMAIMS is exhibit A in the prosecution’s case.

No Comments »

Stanley Kubrick was a consummate perfectionist. Actress Shelly Duvall remembers the shooting of The Shining as 200 days of fake crying and swinging a bat, over and over, sometimes for dozens of takes. There’s a Hollywood joke about how directors get lazier as the day goes on. “At 7:00am, you’re shooting Citizen Kane. At 7:00pm, you’re shooting Plan 9 From Outer Space.” Stanley Kubrick wanted Citizen Kane at 7:00am, Citizen Kane at 7:00pm, and if he could wrangle it, Citizen Kane during his cast’s lunch break.

Stanley Kubrick was a consummate perfectionist. Actress Shelly Duvall remembers the shooting of The Shining as 200 days of fake crying and swinging a bat, over and over, sometimes for dozens of takes. There’s a Hollywood joke about how directors get lazier as the day goes on. “At 7:00am, you’re shooting Citizen Kane. At 7:00pm, you’re shooting Plan 9 From Outer Space.” Stanley Kubrick wanted Citizen Kane at 7:00am, Citizen Kane at 7:00pm, and if he could wrangle it, Citizen Kane during his cast’s lunch break.