Reign in Blood has some great tracks – and not just the two everyone remembers, either.

Reign in Blood has some great tracks – and not just the two everyone remembers, either.

“Epidemic,” for example, has an addictive syncopated gallop riff that’s worth tuning down to Eb so you can play along. “Postmortem” is punchy and powerful, and perfectly leads into “Raining Blood” (the two will be forever linked in the fans’ minds, due to a mastering error that put the first verse of “Raining Blood” at the end of “Postmortem”).

But much of it is an unfocused riff salad, full of tracks that don’t come off as songs but 2-3 minute explosions of energy. “Epidemic” is riff, verse, riff, verse, verse, break, riff, verse, fin! “Criminally Insane” is another half a song that speeds up and slows down in a spontaneous, unplanned way – there’s not really a musical thru-line of tension and release. It’s like it was written by a Turing-incompatible computer.

“Necrophobic” is super fast, but sounds more like four guys trying to set a land speed record than music.

The album’s greatest moment is “Angel of Death”, which has great riffs, a crushing middle break, and lyrics about Nazis. I refuse to believe this was not a marketing strategy. When you’re a female pop duo (think tATu or The Veronicas), you’ve got to have people thinking you’re lipstick lesbians. When you’re a metal band, you’ve got to have people thinking you’re Nazis or Satanists. It worked for KISS and Black Sabbath, so why not Slayer?

The album’s so heavy, fast, and evil that it’s almost overpowering…but I wish it was more consistent. Great riffs share flat space with dull “speed-pick one note until you die of boredom” time fillers. Heavy metal classics rub shoulders with tracks that don’t even sound finished. It’s very uneven moment to moment and minute to minute. Even the vaunted lyrics frequently dissolve turn into shouted tirades about Satan and slashings.

I like Dave Lombardo’s drumming. This is basically the benchmark for metal drumming in 1986. Nobody else was playing this fast or this technically – except perhaps for Dark Angel’s Gene Hoglan. The production is also quite good – sharp and clinical, with clear and crisp allocation of sonic space between the kicks, the rhythm guitars, the what-have-you. The whole affair clocks in at under 30 minutes – say what you will about it, but it does not overstay its welcome.

No Comments »

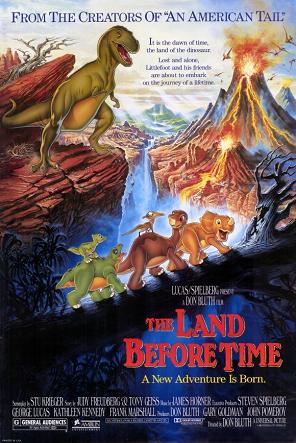

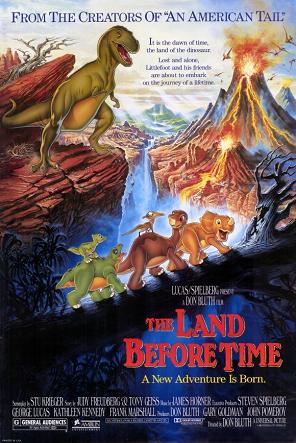

Recent years have been unkind to the dinosaurs, and unkind to this movie. I think the Cretaceous extinction event is still shooting a few final hoops against them as the clock runs down in 2015. We now know that dinosaurs had feathers. And we know that an apatosaurus, a tricerotops, and a pterodactyl in the same scene makes as much sense as a historical movie in which Cleopatra consults George Washington on the construction of the Great Wall of China. But this movie is still powerful.

Recent years have been unkind to the dinosaurs, and unkind to this movie. I think the Cretaceous extinction event is still shooting a few final hoops against them as the clock runs down in 2015. We now know that dinosaurs had feathers. And we know that an apatosaurus, a tricerotops, and a pterodactyl in the same scene makes as much sense as a historical movie in which Cleopatra consults George Washington on the construction of the Great Wall of China. But this movie is still powerful.

And big. That’s mostly what I remembered – creatures inhabiting a landscape that makes everything seem small. That’s what separates it from Disney’s the Lion King – in this movie, nobody’s the king, and even mighty apex predators often end up behind the eightball. The dinosaurs aren’t masters of their domain, they’re struggling to survive in a changing world. The questing youngsters find a kind of sanctuary at the end, but after their travails it seems a bit mocking – like giving a child a lollipop after open heart surgery. That’s the other thing I remember, the gloom.

Otherwise The Land Before Time can be compared to The Lion King quite a bit – some parts line up shot for shot. Tiny creatures scurrying around gigantic paws. A warped, twisted landscape with a palette to match, full of ochre reds and cinerous grays. The death of a parent as a plot device, and divine intervention from that parent’s spirit to close an open plot parenthesis.

The Land Before Time bears the scars of the moviemaking process – certain scenes seem curiously truncated and brief, as if vital footage was slashed out of the movie with an axe. The whole enterprise seems strangely short – barely longer than an hour. Movies about dinosaurs usually slow down and bask in the experience. This one just has young and vulnerable dinosaurs running from danger to danger, which might stress younger viewers.

It’s probably the second best Don Bluth film, behind Secret of NIMH (whose laurels partly belong to another, as it was adapted from a book). Bluth’s animation studio never succeeded taking much market share from Disney, but they probably opened up animation to a few new people. Disney’s movies from this period are hard to watch as an adult – Bluth’s are not. There’s a nice depth to them: not depth in that they’re saying something profound (every Don Bluth movie can be essentially reduced to a “follow your heart” or “believe in yourself” message), but in that there’s a lot of cinematic space explored: subtle interplays of textures and sounds, and occasional unconventional artistic choices.

On the downside, all the dinosaurs have cutesy names for themselves (long-necks, sharp-teeth, etc), sparing us the indignity of antediluvian creatures uttering Latin phylogenetic classifications at the expense of causing my sister to think that those were the actual names for the dinosaurs.

No Comments »

Why is suicide illegal? Because it’s a crime to destroy government property (har har)?. I’ve heard that the truth is that it gives first respondents a pretext to enact drastic measures to save your life. Under normal circumstances, people have the right to refuse medical care.

Why is suicide illegal? Because it’s a crime to destroy government property (har har)?. I’ve heard that the truth is that it gives first respondents a pretext to enact drastic measures to save your life. Under normal circumstances, people have the right to refuse medical care.

From the perspective of third parties, suicide is clearly a bad thing – a get out of jail free card when other people want you to keep playing. But how do you block the dam at the source? How do you stop people from doing it?

You’ve got to persuade them that death is no escape. Here are some methods that have been tried:

1. In the West Indies under Spanish occupation (as recorded by Girolamo Benzoni), vast numbers of men committed suicide by jumping from cliffs or by killing each other. He adds that, out of the two million original inhabitants of Haiti, fewer than 150 survived as a result of the suicides and slaughter (a number that’s hard to believe). In the end the Spaniards, seeing their labor pool dwindle, put a stop to the epidemic of suicides by persuading the Indians that they, too, would kill themselves, and would follow them into the afterlife to inflict fresh tortures. “Kill yourselves, and we’ll be there holding open the gate.”

2. In the Spanish American War, the Moros would strip naked, bind their penises and testicles with green strips of cow hide, and soak the cow hide in salt water, causing it to shrink around their genitals, causing tremendous pain. They were in such agony that they’d attack the enemy in a blind fury and feel nothing, not even a shot to the heart (apparently this is the reason the Americans switched from .38s to .45s, which is not the only time small penises and big guns have gone together, but I go off-piste). The eventual solution to these suicide attacks was to capture the Moros alive, wrap them in a pig skin, bury them up to the neck, and leave them to die. From their perspective, pork meant eternal damnation. When the Americans starting doing this, the situation rapidly returned to normal.

Is there a secular method to deter suicide? Maybe. You’d have to start out with kids, and school them the right way.

“Killing yourself? No. Doesn’t work. The universe always knows. Here’s what happens: you black out from the pills, the bloodied knife falls from your hands, you feel the galvanic surge of the train passing over and through you…and then you wake up, alive and unhurt. The kettle’s boiling. It’s time to go to school, or go to work, or go to nowhere at all. You haven’t escaped. The bottomless abyss just drops you back in other the top. I’ve tried doing it over and over. So have we all. There’s no getting out of here, and we just have to live through it.”

Wouldn’t they have heard of successful suicide victims on the news? People who apparently did what a guy on PUAHate once described to me as “manually stop breathing”?

Maybe you can explain to your kids about how time has a subjective element. For some, it’s a tumbling waterfall. For others, it’s a trickling brook. Maybe for suicide victims, it has the consistency of pitch at room temperature – apparently solid, yet flowing over the course of millions of years. As you kill yourself, your brain captures a moment, and holds it in Zeno’s paradox of increasingly smaller intervals, stretching out eternally.

People who get run over by a train? They’re still under the train.

There’s ways to make suicide seem far less attractive. It involves lying, but maybe suicide victims themselves are already deceiving themselves by imagining an escape route anywhere.

No Comments »

Reign in Blood has some great tracks – and not just the two everyone remembers, either.

Reign in Blood has some great tracks – and not just the two everyone remembers, either.