“I have been accused of caring nothing for the truth, but on the contrary, I value the truth so highly that I make sure it is hidden away someplace safe, where it is not soiled by dirty hands, embarrassed by prying eyes, or worn out through overuse.” – Chairman Trevor Goodchild

Aeon Flux is an animated exploration of psyche and politics. It’s a hard show, a cult hit where “cult” rings truer than “hit”, and it raises questions that carbon-based minds are ill-equipped to answer.

Casual viewers of the show can’t let go of the idea that Aeon Flux’s ambiguities are actually puzzles with solutions. Why are Monica and Bregna fighting? Were Aeon and Trevor ever in a relationship? We’re not supposed to know the answers to these questions, and episodes like “Utopia or Deuteranopia?” (featuring a deluded disciple who painstakingly “deciphers” his master’s encoded notes, only to learn they’re garbled madness) deride you for caring. But it’s still the typical line of analysis Aeon Flux receives: witness this grueling interview where Peter Chung is asked whether Aeon is a robot, a cyborg, or a clone. I mean, she keeps dying and coming back to life and surely there’s a rational explanation for that, right?

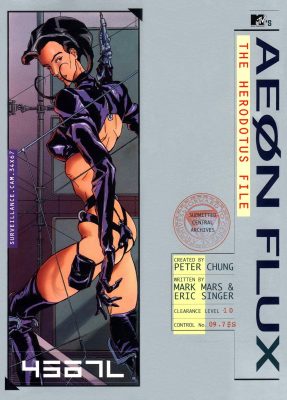

In 1995, MTV’s publishing arm decided to explain Aeon Flux’s universe once and for all – something like The Star Fleet Technical Manual may have been the model – and commissioned a few writers to create a book. I doubt they wanted anything like the Herodotus File, but they still put it in print. It was reissued in 2005 to tie in with the craptacular Charlize Theron movie.

It’s framed in a clever way: as a dossier from Bregna’s internal police. It’s a little like The Screwtape Letters, written by bureaucrats for bureacrats, dripping with a mixture of pathological malice and corporate bullshit.

Basically, Bregnan leader Goodchild seeks to crush a heretical Monican movement that claims that Monica and Bregna were once a single state called Berognica, and the dossier provides rap sheets on all of Monica’s most feared operatives – including Atilda Ram, a 657lb belly-dancer who smuggles contraband inside the folds and orifices of her body, and Loquat, who can adopt any disguise or identity perfectly (even being two different people in the same room!), thus creating uncertainty about whether he/she even exists.

The most fearsome of these characters is Aeon Flux herself, whose interests include infiltration and domination. She does modeling on the side.

The conflict between Bregna and Monica is ultimately just a proxy war for Aeon and Trevor’s deeper, weirder struggle. They have the one of the most unique relationships I’ve ever seen in fiction. They pretend to want to kill each other but clearly don’t. They both ignore countless opportunities to pull the trigger. They care very deeply about each other in a way irreduceable to mere love or hate.

Basically, Trevor Goodchild is a benign Orwellian dictator. He’s not a villain, but he’s often misguided. He wants to progress humanity, and views morality as a constraining process. Or as he puts it: “one doesn’t want to be trapped into making a particular choice simply because it’s right.”

Trevor lives in the hell of every totalitarian dictator; he can’t tell the truth to the people, and his underlings deceive and backstab him in turn. The gulf between what he wants and what he gets is incommensurable. He seeks to build a rational, open society, without secrets, yet he exists in nest of snakes, unable to trust or connect with anyone.

Aeon Flux exists in a hell of her own. She’s free…which means she’s a slave to chance and consequence. She has the liberty of a moth in a flame. Her actions almost always have nasty, unforeseen consequences (both for herself and the people she cares about) and unlike Trevor she can’t even hide behind noble intentions. The reverse of hell is not heaven.

The Herodotus File was written by Mark Mars and Eric Singer. Mars is a colorful guy Peter Chung met at CalArts. He has done virtually nothing aside from Aeon Flux, but he created many of the show’s most electric moments (“ready for the action now, danger boy…?”) Eric Singer was a lowly production assistant who cold-called Chung one day. He is possibly the most financially and critically successful person ever associated with the show (he was nominated for an Oscar Award for American Hustle, and co-wrote an upcoming Tom Cruise vehcle).

The danger of a book like this is that it will talk the show to death. Aeon Flux discusses universal problems of censorship, surveillance, etc. This goes away when you specifically place it (as the movie did) in a particular point in time, such as the far future. Specifics are the enemy.

The book threads this needle by being completely ludicrous, far more comical than the show, and impossible to take seriously. But there’s a lot of wit and fun along the way. The book makes me wish the show had contained a little more of Mars and Singer’s humor to lighten the dourness.

Aeon Flux fans probably can’t trust one word of The Herodotus File. Peter Chung (who had little involvement) says it should be viewed as a work of propaganda or disinformation. Unreliable. It’s a window into the Aeon Flux world, but not an accurate one. Take it as seriously as brings you pleasure.

No Comments »

Some art forms are like staring across a large and flat field. Sunday morning comics (do they still exist?) are all the exact same quality. There are no good ones or bad ones. Garfield could be the best of its kind or the worst. There’s no way to tell. Their bell curve is a bell line: a single vertical stroke that is both infinitesimally thin and high enough to leap into the stratosphere.

2D animation is different: its a plain ridged by great peaks and crevassed by huge gulfs. When it’s bad it’s incredibly bad: the worst thing ever conceived of by the human mind is probably animated. But for me, great animation exists on a level that basically nothing that’s not an animation can touch.

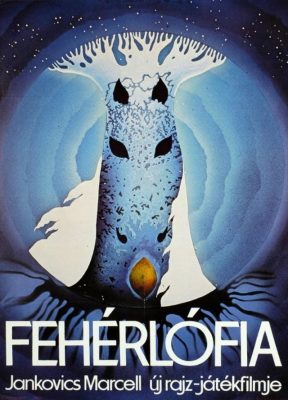

Son of the White Mare, or Fehérlófia, is a 1981 Hungarian animated film that I watched on Peter Chung’s recommendation. I was curious as to what I’d get out of it, considering I know only one Hungarian word, “Tökfej” (lit. “squash-head” but with idiomatic sense between “idiot” and “asshole”), and only because a heavy metal band recorded a song with that title.

It’s like a Disney film, in that it adapts a folk story (in this case, an “ancient Hunnic and Avaric legend” of the three brothers, Fanyüvő, Kőmorzsoló, Vasgyúró, who fought a war against an army of dragons). But where Disney films are reverent as a dull church service, Fehérlófia is energetic and lively. And where Disney films try for styleless realism, Fehérlófia wants to be like nothing you’ve ever seen before.

A realistic myth is a contradiction in terms, and it wastes no time in trying to be “faithful”. Instead, it’s a surrealist vapor that seems made to be inhaled rather than watched. This is one of those midnight movies viewed by college kids who snicker “what drugs were they on?” Probably none. Something can invoke a psychedelic state without being authored in a psychedelic state – it’s probably easier if it isn’t. LSD is formulated by trained chemists, and pressed into pills by machines.

Imagery grows on Fehérlófia’s cel plates like mushrooms on a fallen log. Colors mean things, shapes mean things. It’s a masterclass on how to talk with paint instead of words. I found the voice-acting to be annoying and anti-climactic, and if not for the music (which was nice) I probably would have viewed the film on mute.

There’s a lot of “shape language”, and things get pretty symbolic, with the heroes having rounded, organic shapes and the monsters having an industrial, Soviet brutalist aesthetic. I don’t think Fanyüvő ever calls a dragon a tökfej, but he should have: they’re real pieces of work.

There’s also a psychosexual undercurrent you wouldn’t get from Disney – somehow, Fanyüvő’s sword always ends up hanging between his legs.

It’s technically creative, too. Fehérlófia does not have a single line. Color is allowed to clash directly upon color, without dark penstrokes getting in the way. This gives it a fluidic feel, like watching a lava lamp bubble. And though it might seem the opposite of the “ligne claire“ style of Tintin, it achieves the same effect: combining everything on the frame into the one level. Most animation has a clear distinction between foreground action and background plate. Here, it’s basically all action.

(I’m interested in how exactly the key animator worked. Were lines drawn as a reference and then discarded? Were cels painted freehand?)

It’s a testament to visual storytelling that my illiteracy didn’t seem to matter, because I was fascinated by Fanyüvő’s quest, and the way it was depicted in abstract incinerations of light and color.

The film was created by Marcell Jankovics worked under the auspices of Pannonia Film Studio, one of Hungary’s few native animation studios (One of Pannonia’s alumni includes Gábor Csupó, who co-founded the animation studio known for Rugrats et cetera). He made several films, which have a certain niche appeal. His most famous mainstream moment was probably the film that ended up becoming The Emperor’s New Groove. What’s the the Hungarian version of “Alan Smithee”?

According to IMDB, production was difficult.

According to the director, the animation crew had to work under horrible conditions. Their work building was a rickety wooden construction added to the main studio building. Concept art and other production papers were carelessly littered across the floor and trampled over, as the studio saw no point in preserving them. The celluloid sheets were scratchy and of low quality, and the paint had a tendency to form clumps and crumble off the cels after drying. At one point, 600 completed animation cels had to be thrown out and hastily redone because they were unusable. The animators eventually decided to start manufacturing their own paint, and Jankovics himself helped out with painting the cels. He recalls that the work was so stressful, one of the artists broke out in tears. To buy more production equipment that Pannonia Studio couldn’t afford, the people working on the film even had to take up additional jobs elsewhere.

Movies like this don’t make money. Animation in general was in a slump in the 80s – even Disney was in a precarious situation – and animation for adults has always been a rough sell. The fact that Fehérlófia was made against adverse winds adds to its scrappy charm.

Some things entertain, illuminate, inspire. But some do something more: make a case that their medium is worthy of existence. Fehérlófia is one of the heights of animation. It’s a brilliant, elegant lawyer’s brief for the entire animation genre, showing what’s great about it, and why it’s important.

No Comments »

Most scams are only viable at a small scale. Strangers in Paris might fasten a “friendship bracelet” around a snatched wrist and then demand payment for it, but this trick can’t go beyond a few tourists losing tiny amounts of money. If it becomes too common – with Av des Champs-Élysées flooded with grifters offering bracelets – tourists will get smart and the grift won’t work. There will never be a billion dollar friendship bracelet industry.

There are only about three or four cons that work at scale (thank God). The most prevalent is the bagholder con: borrow money from some people, use their money to inflate your perceived value, borrow a larger amount of money from more people, and then use their money to repay the first.

This scales very well. In fact, it has to scale. The moment there are no new investors – when Paul wants his money back, and no Peter exists to rob – the scheme falls apart.

Ponzi schemes, pyramid schemes, MLM schemes, and stock market pump-and-dumps are riffs on this idea. Karl Marx identified capitalism itself as a bagholder con, requiring ever-increasing profits to support itself. Regardless of whether he was right, the con succeeds because it’s reminiscent of how real investment looks and works. “Today, you pay me x. Tomorrow, I pay you x(1+y).” This can be a healthy thing, rewarding risk-takers and people with vision. Done right, it is nothing less than fiduciary time travel, moving money from the future (where it’s useless) to the present (where it’s not).

“This thing will be worth lots of money tomorrow. If I just had enough cash to get it off the ground…”

But in bagholder cons, the thing is worth nothing. It’s a lemon. It will have no value tomorrow, next week, next year; it is pluperfectly worthless except as the life support system for a speculation bubble. Sometimes there is no “thing” at all, just a wind-filled space. Charles Ponzi’s 1920 scheme (which involved the arbitrate of postal coupons) was exposed because it was physically impossible for Ponzi to be doing what he said he was doing: he’d have needed to mail hundreds of millions of coupons, exceeding all legitimate mail in circulation many times over.

The winners in such schemes are typically people who invest early, have the value of their share pumped by gullible “bag holders”, and then pull their cash out before reality reasserts and the price crashes to the floor.

The losers are the people who get in late, or those don’t sell – those who think that the price crash is some moral test the have to pass.

Technically speaking, anyone who invests in anything is a loser. There’s no way around it. Money has gone from your pocket to someone else’s. You might expect to regain it later, but until that happens and you cash out successfully, you have lost 100% of your investment. This is similar to how any money added to a poker pot should be regarded as lost money – until you win, it’s gone. But gambling is universally seen as either a fun game or a harmful addiction, while investment (at final evaluation, gambling with a business degree) is regarded as responsible financial behavior. You’re building the future! Maybe your own. Maybe someone else’s.

It’s psychologically interesting to watch scammed people in action. Some are innocent naifs who were duped into believing a bad investment was a good one (Charles Ponzi’s scheme was a good example). Sometimes, they’re doubly duped: they think they’re getting in on a scam’s ground floor when the actual mark is them (most MLMs fit this pattern). David W. Maurer’s 1940 book The Big Con describes how surprisingly few victims of cons actually believe the con was a legitimate way of making money. Instead, most believed they were being invited to rip off someone else.

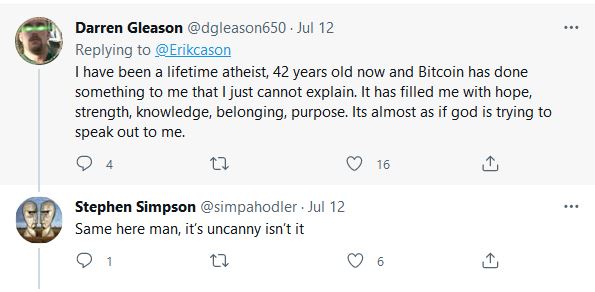

But in either case, the mastermind behind the con does not want anyone to sell. This deflates the bubble, and the bubble’s the only valuable part. So you see conversational patterns cultivated that can only be called cultlike. Unquestioning devotion. Denial of any possible failure. Criticism isn’t tolerated. Questions aren’t asked. Delusional “yeah, we’re all at a party together! WOOO!” styles of rhetoric. There’s a specific way they talk that you don’t see from normal people.

I am suspicious when I see this sort of thing. Hype is a bad signal. It almost looks as if the hype is the entire point, and there’s nothing underneath.

(“hodler” in the second user’s name is affectionate slang for “holding” onto your Bitcoin instead of selling as the price starts to fall.)

In most cases, people with investments have little reason to talk about their investments. If I had a pirate’s treasure map, the last thing I’d do would be to brag about how cool it is to go looking for treasure, or how digging on remote islands will change your life. This can only hurt me, by increasing the odds that the pirate treasure will be found before I get there.

But suppose I didn’t have a pirate’s treasure map. Suppose my income actually came from selling fake maps. Then I might talk about it a lot.

But are cryptocurrencies Ponzi schemes?

The question illustrates a weakness in language. You can say no or yes and be right. Is it literally a Ponzi scheme? No. There are superficial differences. Ponzi schemes are centralized, run by a single criminal, and involve direct transfers of “new money” to pay off old investors. Bitcoin does not have these features.

But if you’re asking “does it share every interesting trait with Ponzi schemes”, I think this is the case.

Every promise of cryptocurrency having real-world utility has thus far failed to materialize. It’s slow, wasteful, expensive, and volatile. Mistakes are permanently written onto an immutable ledger, lost money can’t be recovered, and most solutions (such as “smart contracts”) involve tying the cryptocurrency back to a regulatory body, defeating its purpose.

Various companies adopted Bitcoin in light of the first bubble. Most eventually dropped it, some with frank admissions that it was not suitable for anything except a bubble. Stripe:

Our hope was that Bitcoin could become a universal, decentralized substrate for online transactions and help our customers enable buyers in places that had less credit card penetration or use cases where credit card fees were prohibitive. Over the past year or two, as block size limits have been reached, Bitcoin has evolved to become better-suited to being an asset than being a means of exchange.

Proper investment moves money from the future into the present. Cryptocurrencies do the reverse: move money from the present into the future. Tons of people are still “hodling” as we speak, trying to parlay their savings into a profit in the eternal tomorrow. Because they’ve been told to do so, by people who do not have their interests at heart.

You’ll notice that most cryptocurrency hype focuses, not on things crypto is doing now, but on things that it could do in the future. As David Gerard says, “could” is a misspelling of “doesn’t.”

But this is where we see the main difference between cryptos and Ponzi schemes. They’re bad differences. They

Charles Ponzi was one man. When he ended up in prison. Bitcoin, for example, doesn’t. It’s

Likewise, Ponzi proposed a simple. This could be readily tested against reality, and when it failed, his credibility vanished.

But Bitcoin has no way to fail. One almost thinks it was designed to have no way to fail.

There is no real endpoint Bitcoin is pointed toward. There are several. Evangelists say it will

- Bank the unbanked

- Separate money from the state

- Create a unified world currency

- Protect the economy from crashes

- Enable individuals to transact outside of a legal framework

- etc

Some of these ideas make no sense, and some fight each other. But that’s not the point. This multi-goal argument allows cryptos to continue to seem like a good idea no matter how badly a given prediction fails. It’s a decentralized Ponzi scheme. It takes the bubble and welds nearly unbreakable metal around it, keeping the bagholders from selling.

Bitcoin is propositionally unfalsifiable. No matter how badly a given promise crashes and burns, there’s always going to be something else it could possibly do. You never have to look like an idiot for investing in Bitcoin. You do have to become an idiot, however.

No Comments »