Always described in terms like “absurdist nonsense”, Holy Grail is far from nonsensical or absurd. It depicts a rigorous and orderly world. Its has bones of laws and tendons of logic. Yes, the rules it works by often strange and always arbitrary, but the characters are still forced to follow them, even when the rules are abruptly changed, subverted, or exposed as hollow and meaningless.

It’s a funny but sinister movie: characters are trapped in predefined roles and although they show some awareness of their artificial world, it’s a world they can never escape. Arthur, Lancelot, etc are checker pieces in a game that abruptly changes to chess, to parcheesi, to Mahjongg, to Starcraft II. It’s almost as much a dystopian satire as Brazil.

If the movie has a point, it’s this: “the rules we’re made to follow are all-important…until suddenly they don’t exist.” That’s an important idea in much of the Pythons’ work, and here it is the motor of the story. This dyadic structure (rule -> subversion) occurs again and again, almost too many times to count.

The Peasant. King Arthur justifies his reign with a speech about the Lady of the Lake giving him a magic sword. This is punctured by a peasant’s paraphrased observation “…but isn’t that a really stupid way to elect a leader?” King Arthur can’t answer (beyond saying “shut up!”) because the peasant’s obviously right. It is.

The Black Knight. He blocks King Arthur’s path, and ignores a royal order to step aside. Yes, Arthur fights and defeats him, yet in a weird way, this disempowers him as king. He has no authority over the Black Knight, beyond the strength of his sword arm (what would he have done if he was someone who couldn’t fight well, like a dwarf or an old man?). A king shouldn’t have to fight pointless macho duels against random subjects on the road. If he’s reduced to that, his kingship is either false or meaningless.

The Knights of Ni. Arthur goes on a long, frustrating quest to find a shrubbery, only to return and find that the people he was dealing with have disbanded, reformed under a new name, and have no intent of honoring their deal. His quest is rendered useless by bureaucracy, flipping from all important to futile.

The French. French soldiers occupy a castle on British land, and taunt Arthur for his inability to dislodge them. This further deflates his stature, because (as with the Black Knight), his kingship gives him no actual authority. People can insult, mock, or defy him, and he has little recourse except to insult them back or clumsily try to fight them—tactics of commoners, not kings. This scene has happened many times through history. Foreign colonizers arrive, establish an outpost or a trading colony, and because of a technological advantage like cannons or horses, the regional power can’t do anything. This triggers a regional power shift: the subjects learn that their king’s power was illusory. He wasn’t chosen by God, and wasn’t the last in the line of serpent people. He owned the land because he was able to defend it, and once someone with brass cannons came along, he was no longer able to defend it and didn’t own diddly-squat.

The Legendary Beast. At Castle Aarrgh, the knights are chased into a corner by a horrible monster. Things look grim…until the animator drawing the monster dies, and the monster turns into a harmless drawing (which, of course, it always was)

The Bridgekeeper’s Riddles. Knights try to cross a bridge, but are blocked by a bridgekeeper who asks unfair riddles. Several knights fail and are flung to their deaths. But then Arthur lawyers the scenario’s rules against the Bridgekeeper, gets HIM tossed into the pit, and the remaining knights cross with no further problems. This is a rare example of a character actually manipulating the logic of their world in a positive direction (although Arthur seems to have done so by accident).

So that’s the film. “The rules matter…until they don’t.”

If the Pythons have a point, it’s this: most of society’s instructions are arbitrary, and can be ignored. We could all collectively believe Britain is part of France, and it would become part of France. Often, the future belongs to the powerful and clever and mad, because they have the “hacker mindset”—they can stare past something’s surface illusion and discover its underlying interface. You can try to speedrun a game by playing it “properly” (the way the developers intended). But someone else has found a way to glitch through a wall and has already set the Any% WR.

Yes, the average Joe has to follow rules—people with big sticks tend to whack you if you don’t—but you’re a sucker if you actually believe in them. They aren’t real. They are largely made up by people who want to control you. Do not love the law: it does not love you back. Those who wave a rulebook and say “no fair! A dog can’t play baseball!” are fated to watch a dog dunk on them, over and over, forever.

I do not regard this as a nihilistic AJ Soprano film about how nothing matters. Just that our sense of the world’s shape (and of things like morality and ethics) is a judgment we should make ourselves, rather than accepting someone else’s. Viewed this way, it’s strangely ennobling. All chains are glass. We can imagine the world into new shapes.

I saw this as a kid. It enchanted me as few movies have done. I could not predict where it was going. And this gave the story, despite its surface silliness, a deep underlying realism.

At six years of age, I was noticing already that certain things always happened in movies: the good person always won, the bad person always lost, side characters often died, main characters never did, and so on. Next to these obvious commercial formulas, Holy Grail was scary. Unpredictable. It seemed ruthless and mad, the way characters just horribly died, the way the quest just seemed doomed to fail. It was like a snake in my mind for a long time. Forget the surrealist parts. For the first time, I had seen the world I lived in depicted in a movie.

No Comments »

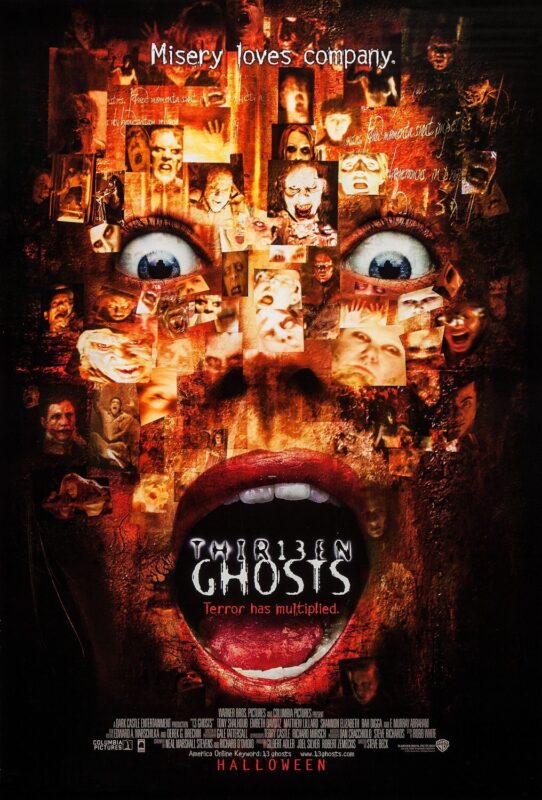

Thir13en Ghosts shows the Dark Castle formula (remaking Fi5ty year old horror movies with Gen X stars and an edgy nu-metal/rap soundtrack) hitting steep diminishing returns on only their Sec2nd film. Hate to see it.

These movies are sort of charming to me now, because they’re wrapped up in era nostalgia. Viewed objectively, they’re very lame and almost pathetic. They obviously started out as a “how do we relate to The Youth of Today?” brainstorming session among extremely middle aged old men, and nearly finish that way, too.

Ninety-n1999ty-nine’s House on Haunted Hill punched a bit above its weight due to good performances and some inspired art direction. It shows the path they could have taken: Vincent Price was forced to gesture toward (and imply) certain topics we can now state plainly and openly, so maybe subtexts of repressed sexual tension and perversion could be explored a bit more.

Yes, there’s only so much mileage to be had in shouting things another movie whispered—eventually more becomes less—but it would have been interesting for the films to really go all out and debauch themselves. Sadly this did not happen. Don’t worry though, Zemeckis and Silver came up with way better ideas, such as “wouldn’t it be funny if Paris Hilton was in a horror movie lol”.

ThirOneThreeEn Ghosts does not particularly punch above its weight and would struggle to KO Glass Joe. There’s no Geoffrey Rush nor Famke Jannsen and nor is there much inspiration. It’s really loud, and seems like a forerunner to the It movies in that I have to watch it with the audio nearly silent and subtitles on otherwise it reduces my eardrums to exploded and atomized dogfood. Also, it has really, really bad acting. Matthew Lillard is actually horrible in the opening scene. It’s several painful minutes of “jeez, was that the best take you got from the guy?”

The plot is farcical. Few movies survive having their plot recapped on Wikipedia but this one sounds particularly like an extended South Park gag. (excerpt: “Kalina explains that the house is a machine powered by captive ghosts, allowing its users to see the past, present, and future. The only way to shut it down is by creating a 13th ghost from a sacrifice of love.”)

Beating up on ThirThirteenEn Ghosts is pointless. This is the offspring you get when Daddy Corporate Balance Sheet and Mommy Corporate Balance Sheet love each other very much. Interesting as a relic from a particular time in horror movies, it’s like a peaceful dinosaur grazing while an asteroid called Saw is streaking down unseen on top of it.

No Comments »

Off I go to see Orchestral Maneuvers in the Dark at Sydney’s Enmore Theater. No. You can’t come. “Off I go” was a rhetorical flourish. I am not going anywhere. I already went and came back and the show already happened and is over…What, you’re already halfway there? Walking? In the rain? How inconvenient.

Question: What makes live music worth experiencing? Versus, say, listening to a better-recorded version of those same songs in your living room along with enticements as “you can change the volume to whatever you like” and “if you lustfully hurl your underwear in the direction of the singer’s voice you can retrieve and wear it afterward?”

Maybe it’s the energy. Maybe it’s the risk. You do not know what will happen at a live concert. You suspect and hope that a musical artist will play some songs, but even that is in the future, undecided and uncertain. Maybe they’ll walk onstage and shoot themselves in the head. Or you in the head. Maybe they’ll declare their newfound allegiance to the British National Party or show off pictures of themselves as AI-generated anime moe girls. The futures massed before us are legion and dark. Swifties get scalped for overprice tickets, but what they’re really paying for is knowledge.

Nothing so dramatic happened at 1,600-capacity Enmore Theater on February the 16th (where OMD played their second show of a two-night run). Instead, the risks I faced were of a more mundane stripe:

- I was told my “seating” is in the stalls at row 0 in “number 6”. I do not know what any of this means. As I walk in, I see six doors marked 1 to 6, and 6 is obstructed. I am told that I need to go through door 2 to get to “number 6”, which is logical. I don’t know why I didn’t think of that.

- I stood near the door, which was a mistake, as all night long people kept coming and going and I had to constantly side-eye the door for incoming traffic.

- The fiftieth time I checked the door, a young woman standing between me and it glared at me, eyes full of steel, and pointedly walked away. I realized later that she probably thought I was trying to stare down the front of her blouse.

- I stood behind a 6’6 man who was constantly coughing and sneezing.

In all, I would liken my experience to the Holocaust.

People will say I am overdramatizing, but I’m sure you’ll agree that my experience had chilling parallels with, say, Auschwitz. I rode a train. I was stamped on the wrist with a number. I was herded like cattle into an area. I was exposed to typhoid. I am currently writing a blog post that is sort of like a diary. I had to listen to an 80s British synthpop band. Really, the Holocaust similarities just keep on coming. I am a survivor. I beheld Eli Wiesel’s night firsthand.

Orchestral Maneuvers in the Dark were sensational live. It was their first Australian tour since (I believe) the mid-80s. Singer Andy McClusky was six weeks removed from throat cancer. They filled the Enmore like an overflowing chalice with sound for two hours. Luminous rivers of sound.

This may not be the last time they set foot on Australia’s beaches (that part is undecided), but they absolutely played like it was.

Orchestral Maneuvers in the Dark

…are an experimental electronic synthpop group from Merseyside (est 1978) by primary school friends Paul Humphreys and Andy McCluskey.

Their music is cold, austere, and history-haunted. Whereas a synthpop band like Tears for Fears is markedly internal (dealing with pain and mental illness), OMD’s most famous material is overtly external, dealing in world affairs and using them as metaphors for concerns of the heart.

They wrote songs about antiquated technology—telegraphs, dynamos, and steam locomotives. When they get touchy feely about a girl, it’s generally mediated through some cultural figure, like Joan of Arc, or Nicola Tesla, or Louise Brooks. Their album covers tend to be minimal, fussy pieces of Vorticist art. You get the sense that world culture could have stopped in 1940 and OMD’s entire career could still have happened.

The track their career launchpadded off—the John Peel-boosted “Electricity”—picks at social waste and overconsumption. But they had no solutions. They were more historians than sloganeers. They were not a particularly political band, unless in the sense that existence is political. “Enola Gay” is about whether a mother should feel proud of her Little Boy. The song does not take a strong stand on the issue. The man who flew the plain was told that if he did not drop the bomb, a ground invasion would kill five million surplus people. Was this ever true? It’s unclear. A trolley problem where the train and tracks are shrouded in fog. But the bomb still fell.

Musically, their early albums have an appealing lightness and lack of substance. They wisp. They drift. Even a raging pop monster like “Enola Gay” sounds like it was transmitted from some far-away station in some bleak battle-zone, corrupted and distorted by the huge gulphs of air it’s winging through. A track like “The Messerschmidt Twins” almost feels risky to listen to—like the song will break like a Seville vase if you do.

The defining OMD album, Architecture and Morality, has a lovely haunted fragility, full of scratches and dirt and swirls of Mellotron ambience. It’s big—with conceptual dance pieces and 3/4 waltz and lavish experiments—yet also very small. The kick drum remains as an anchor to postmodernism, and sometimes it seems to be thumping alone, a heartbeat with nothing to beat against. Only the dark.

A band as frail as OMD has the disadvantage that they can easily be blown over by dominant market trends. German bands like Kraftwerk were their defining influence in the 70s. Tracking forward through their discography, you can see various trends come and go. There’s the detuned snare sound of Bowie’s Low is replaced by the massive noisegated crash of imperial-period Duran Duran. Fairlight CMI synthesizer appear in their middle years (when they enjoyed a short-lived commercial breakthrough in the US). They doggedly kept the “Glitter beat” in service well after its sell-by date on tracks like “Sailing the Seven Seas”. Then, in their later years, they lost identity, lost popularity, and lost their way.

At their biggest they were successful, but not too successful. Their label joked that they were band that “sold gold and returned platinum”—referring to unsold copies of their experimental Dazzle Ships album that were returned from retailers. They never fit in. Their early albums would have sounded very commercial to any cluey fan of German space rock. They were a bit too energetic, muscular, and working-class to pull off the Spandau Ballet-style sophisti-pop they tried later. In a shabby, genteel way, they wear outsider status well.

McCluskey and Humphreys have a kind of “Matt Parker and Trey Stone” relationship. Most of the famous OMD songs were written by McCluskey. He is a far more present member of the band, performing for the press and falooting around on stage (while Humphreys tends to stay behind his wall of synthesizers). But the albums released after Humphreys quit in the 90s are universally seen as the band’s worst. Whatever he does, it seems incredibly important that he remain in OMD.

The Show

I got there at about 7:30pm.

The opening band, The Underground Lovers (Moda Discoteca), was half-finished with their set. They seemed like a loud psychedelic dance group, projecting freaked-out fuzz over the Enmore. The guitarist had an Orange amplifier. No doubt there was a Boss HM2 pedal or two on stage. I did not form an opinion on them one way or the other.

Then OMD took the stage.

After the pre-recorded track “Evolution Of Species”, they took the stage to thunderous applause, then launched into “Anthropocene”, the lead track to their new album Bauhaus Staircase.

Andy McClusky bounced around on stage in fine, effervescent form. He called out a man in the front row who wore a Fender bass T-shirt and was (apparently) miming along to the bass parts to every song. He exchanged banter with Paul Humphries. He made us wave our hands. He started the wrong song and then laughed about it.

Over two hours, we got through an enormous amount of OMD’s back catalog (certainly, most of the parts that are seen as good). The one omission was Dazzle Ships, which wasn’t a glaring omission. It has its fans, but it’s not full of songs the proverbial mailman whistles. It would have been nice to hear “Telegram” though.

This was my chance to hear classics like “Secret” and “So In Love” in a new way – loose, dreamy pieces took on a new weight and life when they reverberated against 1,600 bodies, backed by loud modern kick drums. Fluttery weightless birds reborn as huge phoenixes. “Enola Gay” always seemed a bit depthless on record but landed like a bomb live.

The tracks off Junk Culture remained loud and gaudy. “Tesla Girls” is one of the band’s great songs, whether live or dead. Just an incredible workhorse of a dance track. A song like “Locomotion” never really clicked for me when experienced in .mp3 form, but made a lot more sense with the crowd singing along.

The “Joan of Arc” / “Joan of Arc (Maid of Orleans)” duology is one of my favorite songs, and the canonical OMD track for me. It was wonderful to hear it live. McCluskey is an atheist but effortlessly conjured a kind of suffusive religious awe.

Although the band was obviously playing to a heavy backing track, they do have live drums. The band’s most famous drummer, Malcolm Holmes, is sadly not in touring condition a the moment. In his place was Stuart Kershaw, playing the (often surprisingly strenuous) drum parts. Show-closer “Electricity” has a very quick eighth-note hi-hat beat—his wrist was whipping so fast it blurred into a solid streak of light under the stage lights.

They even dug a track or two out of the fraught Humphriesless period. “Sailing the Seven Seas” was pitched a bit high for McClusky’s throat, and he asked for the crowd to sing loudly to the chorus. They didn’t do “Walking on the Milky Way”, which famously killed the band. McClusky pulled out all the stops writing it, and when it failed to make a commercial impression he took it as a sign that the band was now truly finished. Within a few years, he was Svengali’ing a girl group.

They played quite a few tracks from their new album, Bauhaus Staircase. “Anthropocene”. “Verushka”. “Look at You Now”. “Pandora’s Box.” I have to be honest: have not listened to this album. The song did not make an impression, but maybe for the same reason The Underground Lovers also didn’t: because I lacked a context for it. Opinion to come.

After a three-song encore, we left. I immediately reaped the reward. I rode the train back. I thought about what I had seen. I do not expect to see OMD again, and if I do, it may not have all of the same members I saw tonight. They’ve lost their drummer. Who knows who’s next?

The screen behind them played a selection of music videos and other assorted footage. They had stacks of synthesizers and samplers with them on stage—at one point Humphries had to explain to McClusky how to work some bit of signaling or patching. The band is manna to the “40-60 year old audio engineer demographic”. Every time the lights swept out over the crowd, hundreds of bald middle-aged scalps gleamed.

Despite McCluskey’s infinite reserves of energy, the band also seemed very old. Hunched over their synths, the effect was weirdly poignant: like withered old men, sucked of vitality by terrifying mountains of silicon that were lifeless but also ageless. But they were no older than a good whack of their audience, and the rest will get there in time.

Maybe this is where the interest in history comes through. At the end of the day, the only way to escape death is to flow out of your body and into the books, the cenotaphs, the records. Into an afterlife that is a date and a footnote. Heaven knows the recipe.

No Comments »