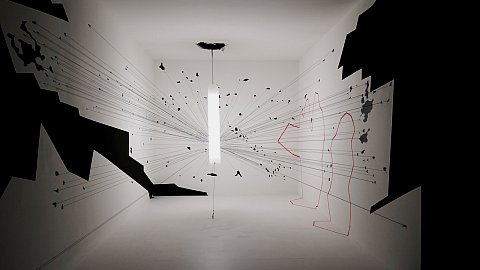

A consequence of modern technology is that you can make very detailed worlds blink in and out of existence by sliding a fader. Enter a number for a noise threshold. Black. Enter a different number. A universe of life pullulates on the screen, florid, dense, intricate as a dendriform fractal. Enter a third, the universe goes dark again. The awe of easily creating something from nothing is cancelled by the fact that your creation can be consigned to the nonexistence with equal ease. Does changing a variable and creating a city that advance the reality of that variable, or remove the reality of that city?

The trick is that technological representations of the world don’t capture the full spectrum of what’s going on. Much like biological senses (heard any good frequencies at 22kHz lately?), they only give us part of the world. A selectively-chosen slice.

Without such filtering, our surroundings would be literally incomprehensible. A meteorologist doesn’t need or want to know the position and angular velocity of every single air molecule on the ground. That would just choke the system with noise, and make eyeball-level analysis of the data impossible. So he views simplified versions of the wind and rain, with the movement of cloudfronts simplified to just a few vectors. This means missing out on fine-grained local scenarios, but that’s fine, so long as he possesses the big picture.

But sometimes the big picture is enclosed within the small picture.

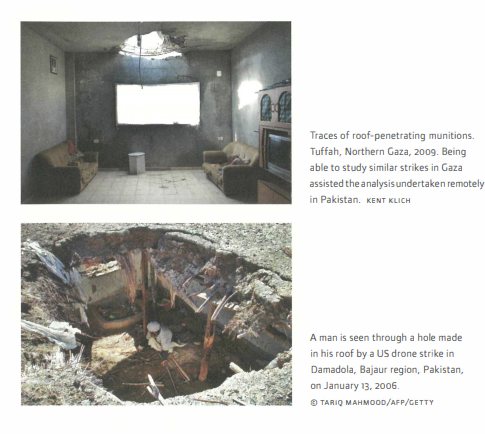

In the late 2000s, drone warfare saw a doctrinal change. Where drones had once been used to eliminate targets in moving cars, now they were striking buildings in dense city centers.

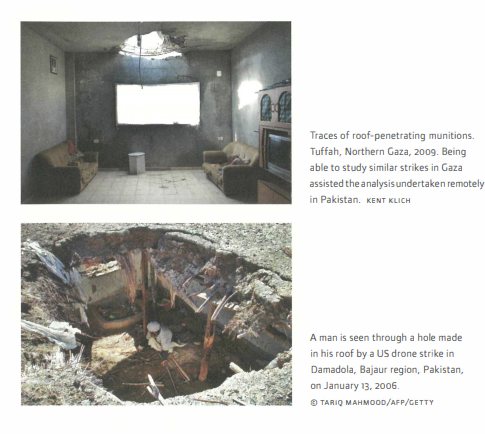

Basically, a missile striking a car leaves a pile of flaming wreckage. It’s visible to everyone. A missile hitting a building will punch a small hole through the roof, and explode inside the building, out of sight. Both will kill, but only one of them makes a mess visible from the air.

This change wasn’t prompted only by tactical concerns, but by propaganda. Coalition forceswanted to fight terrorism in a silent, photogenic way, without giving their enemies PR victories. The mid 2000s saw a dismal march of videos and footage that you can probably remember and name – Abu Ghraib, Collateral Murder, and so forth. The military would prefer that these incidents no longer happen. By incidents, I don’t mean the events themselves. I mean the fact that they were photograph and reached the media.

Millions of dollars are spent designing weapons that don’t look like they’re doing what they’re doing. The “Romeo” Hellfire II or AGM-114R was developed in 2009 and saw mass production in 2012. It features a special charge and delay fuse that adds a few milliseconds between impact and detonation. This allows the Hellfire II to pierce multiple layers of brick, adobe, and concrete before exploding. The fireball happens on the bottom floor, far out of view from the sky.

Remember that drones are used because they are perceived as more “humane” than traditional alternatives. Those who are caught inside their fury – a hailstorm of fragmented steel that shreds flesh from bone – would disagree, but the reality is that the US military would doing something worse if they didn’t exist. Drone strikes are saving lives, when you think about it. It’s cruel to not drone people.

The Hellfire II is used in places where journalists and human rights investigators can’t go. You can’t get reporters on the ground, seeing the fruits of the explosion. The only way to obtain images is from satellite photography.

Photography literally means painting or drawing with light. Digital photographs net the light. They render the infinitely complex detail on a grid of pixels. If an object is smaller than a pixel (and below a threshold for interpolation), it literally disappears. It’s a net, as a fisherman would cast. If the grid is too fine, it trawls up waste and uselessly small fish, eventually choking on its catch. Too big, and you let fish escape.

Satellites, far above the earth, fish for light with a rather loose net. In the 70s, Landsat earth-observation satellites recorded data at 60m/pixel.

At this resolution, the human race barely exists. 99% of our works disappear. Only the largest buildings are 60m long. A single pixel might contain an entire town, lurking unseen.

In the 80s and 90s, satellites refined the resolution to 30m/pixel and 20m/pixel. This is the moment where civilization begins to slide into visiblity. A chemical leak, large explosion, or mass grave might should be visible on a photograph.

This might be the point where it stops. Limitations of technology aside, we’re now the scale human bodies can be seen: a fraught ethical bridge to cross. Surely people have the right to not be watched by a sky-spanning satellite panopticon when they step out of doors. For years, publically-released photographs were legally not allowed to crop closer than this limit.

And as luck would have it, the Hellfire II makes a hole in buildings smaller than 0.5m/pixel – so these strikes technically do not exist, insofar as publically available satellite photography is concerned.

Gutted buildings. Shadows of men flash-burned into walls. All of it, disappeared. Technology does not only enhance our vision, it also degrades our vision, effectively disappearing war, combat, and geopolitical crime.

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism (BIJ) tracked 380 strikes in Pakistan from 2004 to 2014. 62 percent (or 234 incidents) were targeted at domestic buildings. These drone missiles resulted in as many as 1614 civilian casualties in Pakistan alone. But they no longer exist.

Wherefore art thou Romeo?

No Comments »

The Book of Heavy Metal was my least favorite trad power metal album once, but that was ten years ago. Now it’s nostalgic, because the genre has become unimaginably worse. Like reminiscing about a decade-old case of cancer on your skin now that you have it in your nutsack.

Dream Evil were/are a band combining several noxious trends. They’re a Band Named After A Famous Song Or Album. I won’t name names. Let’s just say that once you go past the Rollilng Stones and Judas Priest those drop off in quality. Second, they’re a Band Fronted By A Producer. Those tend to be glossy, polished turds where 90% of the effort was expended on getting the cardioid mic angled perfectly on the speaker cab and 10% writing songs. Third, they’re a Fake Supergroup. Dream Evil was founded in 1999 by Fredrik Nordström on rhythm guitar and Snowy Shaw on drums. Those are your stars. Rounding out the lineup is Peter “who?” Stålfors on bass, Niklas “seriously, who?” Isfeldt on vocals, and Gus “doesn’t count, Firewind wasn’t famous yet” G on lead guitar. They’re all good musicians, but if you have as many Swedish letters in your lineup as you do celebrities, you are probably not a supergroup.

Fourth, and most annoyingly, they’re a Funny Metal Band. You know what I mean. Songs about fighting dragons and drinking beer. They probably have stage costumes that are cute bunny rabbits or something. Wouldn’t that be ironic? Hopefully the four guys in the pit at warmup o’clock get a kick out of it. Everyone else is taking a piss and waiting for the real headliner to take the stage.

Their first album, DragonSlayer, was a solid bit of Hammerfall worship (the one-sentence verdict on Dream Evil is that they worship Hammerfall, but we persist). Their next album had its moments. Now we get to this one, which is a disaster.

When I played the first song, loud noises echoed through my condominion: my own uncontrollable laughter. What a terrible song. The principle riff is the most idiotic I’ve ever heard. The constipated “UHHH! UHHH!” backup vocals in the chorus are just asinine. It’s a quantum anomaly: a four minute song that seems to run for ten. Years ago I tried writing a review, gave up at “I want the Readers Digest version”, and that crap joke is funnier than anything on this disc.

Then we get a good song. “Into the Moonlight.” Actual power metal, with some cool hooks and vocal moments. The band comes together here. Dream Evil always had potential, they just needed to not self-sabotage.

“The Sledge” returns us to moronic gym bro chugging. The Boys(tm) don’t appear to know what a sledge is: it’s a land-based platform that slides across snow or ice on runners, often pulled by a team of dogs. Lines like “It hit me right between the eyes” are confusing: is this a tiny sledge pulled by ants? Maybe they’re thinking of a sledgehammer, but human eyes are about two inches apart, and the head on every sledgehammer I’ve seen is wider than that. Do the band members have Fetal Alcohol Syndrome? Does Sweden have small sledgehammers? I must resolve this mystery.

“No Way”: forgettable and forgotten, a mildly uptempo song that sounds like WASP at their worst (WASPnt, innit?). “Eeeeet’s only rock and roll!” Out of all the famous, distinctive metal vocalists you could have pastiched, you pick Ozzy Osbourne? By the way, if you were waiting for a fast song, this is it. You just heard it. Good decision from Nordström: everyone hates fast songs on power metal CDs.

“Crusader’s Anthem”. Two good songs one album? Sirs, you spoil us! It has Niklas Isfeldt’s best vocal performance, and some crazed blues-inspired soloing from Gus. Someday I want to cull all the good songs off every Dream Evil record: I think there would be enough to make a 12-14 track CD by now.

We’re now trudging through a wasteland of filler, and my interest is flagging. “Let’s Make Rock.” Let’s not. “Tired” does not stick in the memory at all. “Chosen Twice” is a callback to the big song off DragonSlayer, “The Chosen One”. Don’t worry, they changed it by removing the catchy parts. “They calleth us Anti-Christ”. Doth they verily? “M.O.M.” Whatever they’re trying here, nobody cares, least of all me. “The Mirror” is unreviewable, I just heard it and I can’t think of a thing to say. “Only for the Night” has a good main riff (for once in their careers) and a catchy chorus (likewise), but the rest of the song is just drab and unmemorable. That harmonized lead part just stinks of “quick, just give me something that sounds like Iron Maiden!” “The Unbreakable Chain”. Six minutes of this rubbish? “United we are strong / but weak on our own / No one can break this chain.” No, you’re thinking of bundles of sticks. A single chain link is the strongest chain possible. Each new link of a chain makes it weaker, because the chain now has to pull the load plus the weight of the additional chain links. This detour is pointless, like this album.

No Comments »

“I have been accused of caring nothing for the truth, but on the contrary, I value the truth so highly that I make sure it is hidden away someplace safe, where it is not soiled by dirty hands, embarrassed by prying eyes, or worn out through overuse.” – Chairman Trevor Goodchild

Aeon Flux is an animated exploration of psyche and politics. It’s a hard show, a cult hit where “cult” rings truer than “hit”, and it raises questions that carbon-based minds are ill-equipped to answer.

Casual viewers of the show can’t let go of the idea that Aeon Flux’s ambiguities are actually puzzles with solutions. Why are Monica and Bregna fighting? Were Aeon and Trevor ever in a relationship? We’re not supposed to know the answers to these questions, and episodes like “Utopia or Deuteranopia?” (featuring a deluded disciple who painstakingly “deciphers” his master’s encoded notes, only to learn they’re garbled madness) deride you for caring. But it’s still the typical line of analysis Aeon Flux receives: witness this grueling interview where Peter Chung is asked whether Aeon is a robot, a cyborg, or a clone. I mean, she keeps dying and coming back to life and surely there’s a rational explanation for that, right?

In 1995, MTV’s publishing arm decided to explain Aeon Flux’s universe once and for all – something like The Star Fleet Technical Manual may have been the model – and commissioned a few writers to create a book. I doubt they wanted anything like the Herodotus File, but they still put it in print. It was reissued in 2005 to tie in with the craptacular Charlize Theron movie.

It’s framed in a clever way: as a dossier from Bregna’s internal police. It’s a little like The Screwtape Letters, written by bureaucrats for bureacrats, dripping with a mixture of pathological malice and corporate bullshit.

Basically, Bregnan leader Goodchild seeks to crush a heretical Monican movement that claims that Monica and Bregna were once a single state called Berognica, and the dossier provides rap sheets on all of Monica’s most feared operatives – including Atilda Ram, a 657lb belly-dancer who smuggles contraband inside the folds and orifices of her body, and Loquat, who can adopt any disguise or identity perfectly (even being two different people in the same room!), thus creating uncertainty about whether he/she even exists.

The most fearsome of these characters is Aeon Flux herself, whose interests include infiltration and domination. She does modeling on the side.

The conflict between Bregna and Monica is ultimately just a proxy war for Aeon and Trevor’s deeper, weirder struggle. They have the one of the most unique relationships I’ve ever seen in fiction. They pretend to want to kill each other but clearly don’t. They both ignore countless opportunities to pull the trigger. They care very deeply about each other in a way irreduceable to mere love or hate.

Basically, Trevor Goodchild is a benign Orwellian dictator. He’s not a villain, but he’s often misguided. He wants to progress humanity, and views morality as a constraining process. Or as he puts it: “one doesn’t want to be trapped into making a particular choice simply because it’s right.”

Trevor lives in the hell of every totalitarian dictator; he can’t tell the truth to the people, and his underlings deceive and backstab him in turn. The gulf between what he wants and what he gets is incommensurable. He seeks to build a rational, open society, without secrets, yet he exists in nest of snakes, unable to trust or connect with anyone.

Aeon Flux exists in a hell of her own. She’s free…which means she’s a slave to chance and consequence. She has the liberty of a moth in a flame. Her actions almost always have nasty, unforeseen consequences (both for herself and the people she cares about) and unlike Trevor she can’t even hide behind noble intentions. The reverse of hell is not heaven.

The Herodotus File was written by Mark Mars and Eric Singer. Mars is a colorful guy Peter Chung met at CalArts. He has done virtually nothing aside from Aeon Flux, but he created many of the show’s most electric moments (“ready for the action now, danger boy…?”) Eric Singer was a lowly production assistant who cold-called Chung one day. He is possibly the most financially and critically successful person ever associated with the show (he was nominated for an Oscar Award for American Hustle, and co-wrote an upcoming Tom Cruise vehcle).

The danger of a book like this is that it will talk the show to death. Aeon Flux discusses universal problems of censorship, surveillance, etc. This goes away when you specifically place it (as the movie did) in a particular point in time, such as the far future. Specifics are the enemy.

The book threads this needle by being completely ludicrous, far more comical than the show, and impossible to take seriously. But there’s a lot of wit and fun along the way. The book makes me wish the show had contained a little more of Mars and Singer’s humor to lighten the dourness.

Aeon Flux fans probably can’t trust one word of The Herodotus File. Peter Chung (who had little involvement) says it should be viewed as a work of propaganda or disinformation. Unreliable. It’s a window into the Aeon Flux world, but not an accurate one. Take it as seriously as brings you pleasure.

No Comments »