“Swifties” (or “Tom Swifties”) are one-line jokes where a quotative adverb relates in an amusingly literal way to the quotation before it. For example:

“‘We must hurry,’ Tom said swiftly.”

They are known for being fun to create and painful to read. Here are some of my own. Be warned that unlicensed manufacture and consumption of Swifties is an indictable offense in 32 countries.

* * *

“We’re just getting more and more lost!” Tom said antipathically.

“I’ve been cast in a Gene Wilder biopic,” Tom said bewilderedly.

“My Hitler mustache is going gray,” Tom said old-fashionedly.

“They should teach flag-recognition at school,” Tom said vexedly.

“I’m feeding my son William weight-gainer shakes so he can play pro football,” Tom said, bulk-billing the NFL.

“I’m in the hull of a Nicaraguan guerilla boat,” Tom said in contrapunt.

“Japanese broth tastes better with alcohol,” Tom said misogynistically.

“People in Minoa are easily scammed,” Θωμάς said concretely.

“My pants have disappeared,” Tom said with embarrassment.

“Just because I’m the original man doesn’t mean I don’t have manners,” Adam said urgently.

“I would prostitute myself for AMD’s new 5650X processor,” Tom said horizontally.

“Swiss particle physicists often have criminal convictions,” Tom said with concern.

“Stay back, or I’ll use my teeth!” Tom said ambitiously.

“I watch The Nanny for the actress’s facial gestures,” Tom said frantically.

“When I wore this skunk costume, I became strangely attracted to women,” Ms Blanchett bifurcated.

“I roll a d20 and stab the orc with a syringe! It does maximum damage!” Tom said hypocritically.

“Your nativity set is missing the three wise men,” Tom said imaginatively.

No Comments »

I can remain silent no longer on an important topic: glam rock isn’t the same as glam metal. Not at all. Anyone who writes “glam rock/metal” (as though these are fuzzy or interrelated concepts) deserves to feel the sting of the lash across their pitiful shoulders.

“Glam rock” is a style that became popular in Great Britain in the early 70s: think Wizzard, T-Rex, and Roxy Music and also think platform boots, scarves, glitter, and flared jeans. The music was 50s-inspired rock and roll with a warm, summery vibe. Glam rock could be pretentiously analyzed as “radical self-manufacture”: its stars were big and cartoony and fake, but not in an “I’m lying to you” way. It was more like “I’m inviting you into a shared dream”. For a few years, the dream was so compelling that audiences accepted the invitation. You could really believe that David Bowie was an alien, Marc Bolan an elf, and Gary Glitter a good bloke with an unimpeachable internet search history.

Glam rock collapsed after three years, replaced by disco and limp-wristed parodies of itself (Mud, Bay City Rollers, Insert Third Example). Bowie salvaged his career from the glitter-strewn rubble; nobody else did. Look at the post-1975 discography of a middle-of-the-pack glam band you’ll see five or six flop albums in a row (with titles like Remember Us? and We’re Back! and Will This Work? and Our Manager Made Us Hire a Bagpipe Player), followed by a break up, followed by a 2001 nostalgia concert featuring two original members, followed by the end.

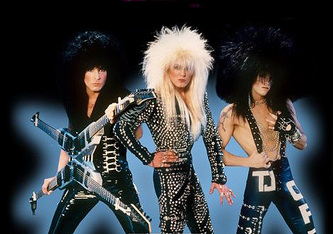

That’s glam rock. Glam metal (also known as hair metal) is very different: a variant of NWOBHM that became popular in Los Angeles in the mid-to-late 80s. Famous bands include Motley Crue, Poison, and so forth. Like glam rock it had outrageous fashion sense, but unlike glam rock it was always the same fashion sense. Bolan didn’t look like Bowie who didn’t look like Brian Ferry, but all glam metal bands dressed the same.

Glam metal was ugly, cynical, and had no soul. Track one would be about fisting a hooker’s ass. Track 2 would be an overwrought ballad about the power of love. It was plastic music, totally disingenuous and shameless about it. It snorted rails of coke off the bottom of the barrel. Tucker Max once said there are “beer and girls” people (those who party to have fun) and “coke and strippers” people (those who party as an act of nihilistic self-destruction). Glam metal was the soundtrack for the letter. The music wasn’t feel-good, it was feel-dead, and often become-dead: Motley Crue’s “Kickstart My Heart” is about Nikki Sixx being resuscitated after going into drug-induced cardiac arrest. Five years earlier, his singer had killed a man in an alcohol-induced car accident. Were you in an 80s glam metal band? I’m sorry that your music career is over, but at least you now have a tear-jerker biography about overcoming addiction to sell to a major publisher.

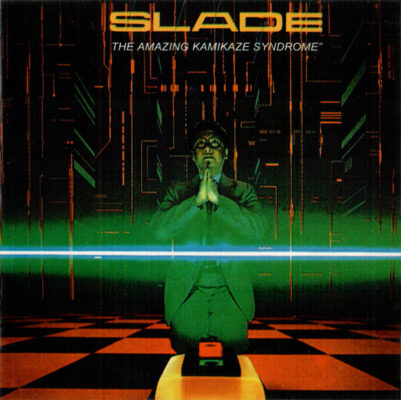

So why do I bring all this up in a review of a half-forgotten Slade album? Because they’re notable as one of the few bands that played both styles.

They achieved fame in the 70s as part of the glam rock movement: they had six UK number ones. I don’t know why they’re called Slade. Like many glam bands they had a gimmick: they spelled the names of their songs wrong. “Mama Weer All Crazee Now”, “Skweeze Me, Pleeze Me”…I used to think there was a sharp line between artistic affect and crippling dyslexia, but Slade proves that it’s all just gray.

It wasn’t all smooth sailing. Slade had the profound misfortune of having “Merry Xmas Everybody” as their biggest chart success. A Christmas song is the worst kind of hit you can have: it means you become pigeonholed as a naff novelty band. It also means the world forgets you exist for 51 weeks out of the year.

After “Merry Xmas Everybody”, glam rock became unpopular and Slade’s number ones (and soon twos, etc) stopped coming. But in 1983 they managed a minor comeback with The Amazing Kamikaze Syndrome, which broke them in America with a harder, metal-tinged sound.

It’s a loud, hard-rocking and sleazy record. The guitars are like a brick wall and the vocals are like diamond chainsaw tearing through that wall: I don’t know how Noddy Holder’s voice survived so many years of abuse, but science is still asking that question of Nikki Sixx’s heart. “Run Runaway” is a great song, with Jim Lea somehow making an electric fiddle work in a pop context. “Slam the Hammer Down” could almost be a Chuck Berry song, although 80s technology turns it into a massive steroid-pumped gorilla of a track, almost scary to listen to. You feel as if you could get crushed by it.

When the rock-all-the-time approach gets old, you get the eight-minute-plus “Ready to Explode”, which is a weird metal epic combining Queen, Meat Loaf, The Cars, and Iron Maiden. The band pulls influences from just about anywhere, but surprisingly they make most of them work. “My Oh My” is a power ballad with drums so reverb-drenched they might have been recorded from the bottom of the Grand Canyon. It’s like a parody of what music sounded like in the 80s, but it flows nicely and is quite memorable.

“(And Now the Waltz) C’est La Vie” was an odd choice for a single – a Broadway-style ballad with drums that never seem to land where you’d expect. The rest of the album finds the band taking no risks and playing to their strengths, delivering guitar-driven songs with keyboards adding a little color.

Slade wasn’t able to sustain this level of success. Soon they went back being a nostalgia band, and while this isn’t the worst kind of death, it’s a death regardless. Their biggest impact in the 80s might have been the fact that Quiet Riot covered one of their hits. It’s good that they managed this little comeback, but (with typical Slade) bad luck glam metal imploded beneath them just as suddenly as glam rock had. It’s like being aboard a sinking ship and getting rescued by the RMS Titanic.

No Comments »

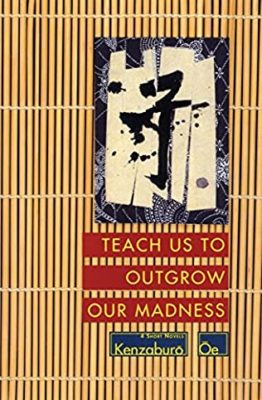

On August 15, 1945, a Japanese schoolboy heard the voice of god crackling from a transistor radio.

“We have ordered our government to communicate to the governments of the United States, Great Britain, China and the Soviet Union that our empire accepts the provisions of their joint declaration…”

The Surrender Speech was the first time the Showa Emperor had ever spoken to the common people, and it destroyed young Kenzaburo Oe’s faith. He’d thought that God-Emperor was… a god. He’d had dreams of a massive bird, soaring over Japan like a protecting shield, pinfeathers tearing through the sky like blades. To hear the Emperor speak in a man’s voice (which his schoolmates could mockingly imitate) took a hammer to his spirit.

Occupation soldiers rolled into Oe’s mountain village later that year. He expected the Americans to slaughter them all; instead they gave the villagers candy bars. This seemed incomprehensibly cruel to Oe. He’d expected death; had received disillusion. Everyone had lied to him. The Emperor wasn’t a god, the Americans weren’t devils, and if he was to die for a noble cause, he would first have to find one.

The inner turmoil of this moment colors much/all of Oe’s subsequent writing. Teach Us to Outgrow Our Madness is a collection of four novellas, grappling with a past that has proven to be unreliable.

“Aghwee the Sky Monster” is a surrealist tale similar to Gogol. The narrator becomes the friend of the mononymous “D”, a mad composer who is haunted by the ghost of his son Aghwee (who appears to him as “a fat baby in a white cotton nightgown, big as a kangaroo”). Only D can see this apparition, with whom he conducts nonsensical conversations .

Aghwee is obviously a delusion. Or is he? His existence controls and shapes D’s behavior in the same way a real baby would (for example, D will avoid dogs because he doesn’t want to startle Aghwee, who’s afraid of them), so does he exist in a phenomenological sense? The narrator probes D’s past, finds deep and unhealed wounds, and even horror. It might be D’s deserved fate to carry Aghwee with him eternally.

Shiiku, or “Prize Stock”, is about a black American pilot who crashes in a remote Japanese village. He is chained up and regarded with a mixture of awe and hillbilly racism. I’ve seen some people online describe this story as “autobiographical”, although it couldn’t be – there were no black pilots in the Pacific Theater. I think Oe’s offering some commentary on Japanese wartime propaganda, which contrasted “enlightened” Japan with the socially backward US. The US had consigned generations of blacks to slavery, a medieval institution that Japan had abolished centuries ago (Japan’s ~20 million Chinese and Javanese “forced laborers” were not regarded as slaves). The IJN conducted so-called “Negro Propaganda Operations” – covert short-wave radio broadcasts attempting to recruit African Americans to the Axis cause. “Prize Stock” is caustic commentary on Japan’s supposed post-racial politics. They were more like Americans than they thought.

“Teach Us to Outgrow Our Madness” is about a fat Japanese father and his disabled son Eeyore (this is another repeated theme of Oe’s, whose own son has severe autism) who have several supernatural adventures. My least favorite story: it reprises themes expressed more eloquently elsewhere.

Then there’s the monolithic “The Day He Himself Shall Wipe My Tears Away”, a long and intricate story that has to be read carefully: there are tricky perspective shifts. In short, it’s about a man who is dying in hospital of a “cancer” that is almost certainly imaginary. Descending into the story is descending into a tangled web, there’s narratives within narratives, lies within lies, houses built on quicksand, quicksand built on quicksand, etc.

It’s like a Fellini movie, none of the facts are that important: they only matter insofar as they illuminate the mental landscape of a profoundly deluded man. He’s arrogant, proud, self-pitying, defensive, and not particularly sympathetic. The lunatic in “Aghwee” is suffering from madness as a form of penance. The hero of “The Day…” wears insanity like protective armor. Apparently this is Oe’s veiled roman-à-clef of Yukio Mishima, author and poet turned right-wing nationalist who had committed seppuku two years previously, following a failed coup attempt.

So all four stories are personal, yet they’re bigger than Oe. He shows the way a person can forcibly have the fabric of a nation threaded into his skin, and the pain of having that fabric torn away. What’s the use of memories? To show us what happened in the past? Or to guide our behavior in the present? The two goals are often incompatible.

It asks questions such as “what’s a nation founded upon?” Sometimes, the answer is “nothing”. Take Algeria. Why does Algeria exist? For no reason. It’s just there. But then you have “proposition” nations, which are founded (or believe themselves founded) upon an ideal or belief. I’d say that the United States, modern-day Israel, and Showa-era Japan fall into this category.

Generally it’s bad to be a proposition nation, because you run the risk of your proposition being proven false. What happens then? What happens if you’re the Independent State of Phlogiston? The Republic of Timecube? You lie, I guess. You deceive your citizens, deceive yourself, because the only other course is ruin. Japan could have never have won the Second World War. It persisted on in denial of this fact. Its soldiers were fighting a hopeless war, and Kenzaburo Oe was being raised to throw himself into a meat grinder. Nobody had any plan to win. The nation just staggered blindly forward, deeper into the disaster, inflicting psychic trauma on its citizens that lasted for years. State-sponsored falsehoods continue in memory long after the state falls to pieces.

After the war ended, Japan spent minimizing its war crimes: writing arrant falsehoods into its history books. Men who had produced mountains of bodies went unpunished and were reassimilated back into society. Oe’s childhood disillusionment could have been worse: he wasn’t told about Nanking or Unit 731. D is burdened by an imaginary baby, the protag of “Day” is burdened by an imaginary cancer, and Japan was burdened by an imaginary history. Even in the 70s there were men like Mishima, who literally killed himself in service of the false god.

Oe achieved fame in Japan due to work like Teach Us to Outgrow Our Madness, but it’s easier to forgive than to forget. In 1994, he was named to receive Japan’s Order of Culture. When he learned that he would receive the Order from the Emperor’s hand, he refused.

No Comments »