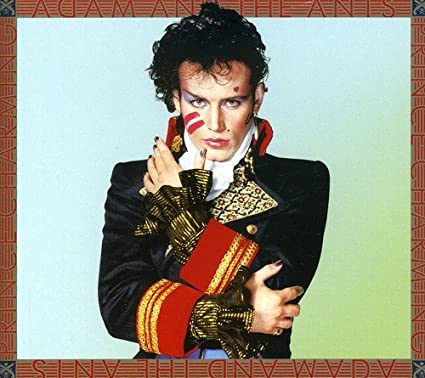

Bowie had a stock response to chameleon comparisons: “a chameleon’s trying to make you ignore him…that’s not my ambition!” Nor was it Adam Ant’s, who came from a similar art school background and cycled through an even more outlandish cast of characters: Indian brave, highwayman, cossack: visuals that sold (and were sold by in turn) some of the most exciting songs of the early 80s.

The first Adam and the Ants record is jittery, cold, and fraught, like ice cubes rattling in a glass. The second is a much easier listen, featuring powerful African-influenced drumming and really catchy songs. This is the third, which, as the title would suggest, is extremely charming and easy to like. It thus overcomes big problems, such as nearly every song on side B sucking.

It’s made of similar stuff to Dog Eat Dog, meaning sharp layers of vocals and guitars interspersed with empty space that crackles with energy. There isn’t the omnipresent Burundi drumming of Dog, but the busy tom fills achieve much the same effect. “Scorpios” is a nice, sprawling song with horns and many-tracked vocals that seems to stretch itself out on the airwaves. “Picasso Visita El Planeta De Los Simios” is even better, featuring lacerating funk-inspired guitar. “Stand and Deliver” is an amazing classic that summarises Adam Ant’s career, like a leaf that looks exactly like the tree it came from. Energetic danceable post-punk decked in brilliant visuals that saturate the music beneath it.

Quality control issues become evident as Prince Charming progresses. “Mile High Club”: dogshit. “Mowhok”: dogshit. “Ant Rap”: dogshit inexplicably released as a single. This is another trend of Ant: about half the songs absolutely do not work, despite containing similar ingredients as the ones that do. At least the bad songs mostly run together this time, so skip button jockeying isn’t necessary.

Ant broke through in the gulf between two eras, like a surfer trading one wave for another. The Ants were originally signed (according to Adam) because Decca Records wanted “in” on the then-waning punk rock trend, and grabbed the nearest band to hand. Then they blew up in the MTV music video era, when listeners started using their eyes as well as their ears and it began to pay to not be an absolutely hideous fucking goblin.

You know what they say about Elvis: 90% of what he did was worthless, and the last 10% made him king. Adam Ant was inconsistent, but when he was good, he was very good. You might say he burglarized the king.

No Comments »

I heard the band Motorhead described as a perfect mix of 1/3 punk rock, 1/3 heavy metal, and 1/3 rock and roll, with no element outweighing the other.

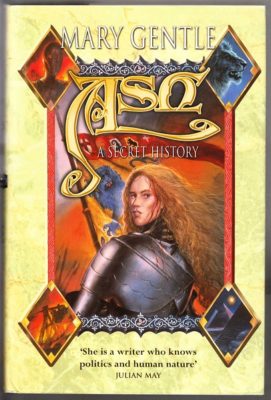

This book is a mix of 1/3 fantasy, 1/3 alternate history, and 1/3 science fiction. It hooked me at age 12 because of its violence: if you want detailed descriptions of billhooks crushing skulls, this has them. Descriptions, I mean. But Ash: A Secret History is ambitious: the plot unfolds like Lemarchand’s box, becoming increasingly complex and intriguing.

It’s a book within a book within a book. The framing device is that a 20th century linguist is attempting to publish a biography of the female medieval mercenary captain, Ash, who lived in the 14th century and who is shrouded by myth and legend. She had a reputation for tactical brilliance. She also heard voices in her head, telling her the future. Or so the tales say.

The book soon starts getting weird. There are big hints that the world of Ash (and the biographer) is not our own. Christ wasn’t crucified on a cross, he was hung from a tree. The Visigoths didn’t disappear from history in the 8th century, they rebuilt the city of Carthage and established an empire on the northern coast of Africa. Certain world events went differently.

By the time quantum physics start getting involved the book, you’re heavily invested in its tale of bloodshed and war. Ash ends up defending 14th century Burgundy against an army of invading Visigoths – a bizarre war that’s found nowhere in history. Is it all a hoax? Are we are hoax? Are the true hoaxes the friends we made along the way?

The way the plot resolves is clever, but at every level the book is interesting: you feel sorry for the historian who wrote down Ash’s adventures and paid a terrible price for it, and for the modern-day linguist who keeps having the rug yanked out from under his feet by inconvenient historical discoveries (one wonders if Gentle isn’t writing about her own experiences in academia).

It’s not flawless – a lot of dialog scenes serve no purpose except to gargle and masticate information the reader already knows, and every conversation seems to run about thirty percent too long. But on the whole, it’s a superior work, unlike any story I can recall reading.

As I’ve alluded, Gentle is a heavily-credentialed midlist author with degrees in Seventeenth Century Studies and War Studies. She seems to be one of those writers who turns converts masters degrees into novels. Ash can a brutal book, revelling in blood, sordidness, and bathroom activities, and the fact that it’s also thoroughly researched and informative offsets this. Like George MacDonald Fraser before her, Gentle realises that the audience will tolerate a lot of depravity if you present it as an educational experience.

No Comments »

“I don’t remember giving a moment’s thought to the fact that we had just sketched out a plan to kill millions of people.”

Ken Alibek – born Kanatzhan “Kanat” Alibekov – was a Soviet microbiologist. Prior to his defection to the United States in 1992, Alibek was First Deputy Director of Biopreparat, the USSR’s secret biowarfare project.

In other news, I might be dying right now. Something deadly might be in my body, invisibly small, eluding my T-cells and multiplying like a gathering snowfall underneath my skin. My killer has no face. Like a citizen in Kabul being targeted by a reaper drone, my loved ones won’t be able to curse my murderer or exact revenge on it. My body will go into a plague bag, then into a cremation oven. If I have a legacy, it will be the infection of others.

Disease is everywhere. “You Want It, You Got It,” sang the Detroit Emeralds in the 70s. Disease is “You Don’t Want It, You Got It”. I live in a first world country with plumbing and sewage, yet I’ve had the flu, chicken-pox, and at least forty colds. Viruses are as inescapable as air – and to an approximation, viruses are air. 800 million viruses drift to earth every day per square meter, a steady rain, as deadly as a storm of steel. These viruses clash and recombine, peeling off strips of recombinant DNA and RNA like Formula One cars swapping paint, making themselves stronger in the process, climbing up evolution’s ladder. A deadly new superplague might now be inside my lungs. It’s unlikely to happen, but that’s chilly comfort. Someone, somewhere is going to be the first.

And these are natural plagues, constrained by evolutionary limitations. Engineered ones are far worse. Nature can create shapes that float on water, such as curved leaves, but only man can build the Nimitz-class aircraft carrier. The biohazards Alibek works on are synthetic tularemia, anthrax, glanders, haemorraghic fever, and anthrax. But the true biohazard is Abelikov himself. He was a sorcerer of the spirochete, driving nature beyond its natural constraints and then straight over a cliff.

“We saw ourselves as custodians of a mystery that no one else understood, warriors or high priests of a secret cult whose rituals could not be revealed.”

The thing about viruses is that they can’t be too deadly, or they’ll kill their carrier organisms before they can spread and thus become extinct themselves. A man-made plague distributed from airborne canisters is under no such obligations to play nice. Alibek wasn’t the first to see the potential of disease as a weapon – we’ve been catapulting rotting cattle over city walls since antiquity – but backed by the Soviet military apparatus, he took it to a never-before-seen level. It’s impersonal, creating a layer of obfuscation between the attacker and victim. And it’s easy for a state actor to work on bioweapon projects, telling outside inspectors that they’re merely conducting defensive research.

But weaponized diseases have a big problem: they can’t tell friend from foe. Alibek and his fellow researchers are playing with fire, and he has many close calls at Biopreparat, such as a terrifying incident in 1983 where a faulty safety valve causes a liquified super-strain of tularemia to flow upwards through an air vent.

“I opened the door and took a few steps inside. It was pitch black. I reached back, groping in the darkness for the light switch. When I finally hit the switch and looked down, I found I was standing in a puddle of liquid tularemia. It was milky brown–the highest possible concentration. The puddle at my feet was only a few centimeters deep, but there was enough tularemia on the floor to infect the entire population of the Soviet Union.”

Alibek frantically washes himself with hydrogen peroxide. It isn’t enough. One day later, he begins to sicken.

Toward the end of Klyucherov’s visit, my body started to shake. Chills, and a sudden wave of nausea, overcame me so quickly I wanted to bury my head in my arms. It’s a cold, I thought. I’ve been working too hard.

But it felt worse than any cold I’d ever had. I could feel my face burning with fever.

“What’s happened to you?” Klyucherov asked in a tone that was now much friendlier. “You look like you’re about to die.”

I smiled weakly. “It’s just a cold,” I said. “I had a long night. I could do with some tea.”

Alibek isn’t just afraid of the disease, he’s afraid of discovery: this kind of fuck-up that will cause him to disappear. Luckily, he’s able to antidote himself with black market tetracycline, and his superiors never suspect it was anything but a cold.

This was one of the most fascinating parts of the book for me: the discussion of Soviet culture and how one interacts with it.

Russia had several Chernobyl-like events. And in every case, they were made worse by scared technicians trying to cover it up. On March 1979, a technician at a Sverdlovsk chemical drying plant removed a clogged filter and forgot to replace it. Aerosolized spores were soon pouring from the plant’s exhaust pipes, and the wind blew them into Sverdlovsk’s factory district. What kind of spores? Bacillus anthracis, which is better known as anthrax.

Workers began dying in their dozens. Several contradictory coverup stories went into effect at once. The KGB informed locals that the deaths were caused by a truckload of contaminated meat. Innocent meat vendors were arrested, and the victims’ families received visits from “doctors” armed with falsified death certificates. Meanwhile, members of the local Communist Party were put to work scrubbing “hazardous material” from roads and rooftiles.

…which caused a second wave of deaths, because the brooms and brushes swept anthrax spores back into the air, spreading them a second time throughout the city. Multiple layers of incompetence, executed with maximal efficiency.

I don’t think any kid dreams of working at a place like Biopreparat. Alibek originally wanted to become a military psychiatrist, but he was drawn sideways into studying epidemiology and biology. He has an obvious flair for such work, but he also possesses a single large weakness: he notices things he’s not supposed to. His professor, a retired colonel called Aksyonenko, assigns him the task of writing about the outbreak of tularemia that crippled a German offensive in 1942. After a few nights studying the case, Alibek came to conclusions that might have landed him in big trouble.

When I walked into my professor’s office with a draft of my paper, I thought I had solved the puzzle. He was concentrating on the latest edition of Krasnaya Zvezda, the official army newspaper.

“So, what have you discovered?” Aksyonenko asked, smiling up at me before returning to his paper.

“I’ve studied the records, Colonel,” I said cautiously. “The pattern of the disease doesn’t suggest a natural outbreak.”

He looked up sharply. “What does it suggest?”

“It suggests that this epidemic was caused intentionally.”

He cut me off before I could continue.

“Please,” he said softly. “I want you to do me a favor and forget you ever said what you just did.”

Whether or not you think Reagan was correct in describing the USSR as an “evil empire” (I think he was), it was certainly an unsafe empire. When disasters like Chernobyl (or Sverdlovsk) occur, they need to occur under bright light. Everyone needs to know what went wrong, and how, so that a correct response can occur. Not beneath the shade of coverups and lies. Most importantly, you need to give your inferiors permission to make mistakes. Otherwise you’ll simply train them to be good liars, and you’ll never know when things go wrong.

Obviously, Biopreparat’s work killed a good number of Russians. Was it ever used on non-Russians?

Not in war, as far as I can tell. But the strength of biowarfare is that it can be used in ways that specifically aren’t sanctioned warfare; such as against civilians and political opponents. Alibek has numerous encounters with KGB operatives, who praise him, threaten him, attempt to recruit him as an informant, etc. He suspects that his work is used to commit assassinations on behalf of a government venture called Project Flute.

In the spring of 1990, Butuzov walked into my office and sank into the big armchair across from my desk. He stared for a while at the

portraits of scientists hanging on the wall.

“I need your advice on something, Kan,” he said casually.

“Sure,” I said. “Professional or personal?”

“Professional.”

I waited until he spoke again.

“I’m looking for something that will work with a gadget I’ve designed. It’s a small battery, the kind you use for watches, connected to a vibrating plate and an electric element.”

“Go on,” I said. He spoke in the same casual tone in which we discussed a soccer match. I was fascinated.

“Well, when you charge this element up, the plate will start vibrating

at a high frequency, right?”

“Right.”

“So, if you had a speck of dried powder on that plate, it will start to form an aerosol when it vibrates.”

He looked at me for encouragement, and I motioned for him to continue.

“Let’s say we put this assembly into a tiny box, maybe an empty pack of Marlboro cigarettes, and then find a way to put the pack under someone’s desk, or in his trash basket. If we were then to set it in motion, the aerosol would do the job right away, wouldn’t it?”

“It depends on the agent,” I said.”Well, that’s what I wanted to ask you about. What’s the best agent to use in such a situation if the objective is death?”

I’m not sure why I went along with him, but I did.

“You could use minimal amounts of tularemia,” I said, “but it wouldn’t necessarily kill.”

“I know,” said Butuzov. “We were thinking of something like Ebola.”

“That would work. But you’d have a high probability of killing not just this person, but everyone around him.”

“That wouldn’t matter.”

Alibek continues probing, and learns that Flute’s target is Zviad Gamsakhurdia, the newly elected president of Georgia. The “flamboyantly mustachio’d” Gamsakhurdia had been an enemy of Moscow ever since leading a campaign against the Soviet army in 1989, and it was politically attractive to the Kremlin that he not remain in power.

Zviad Gamsakhurdia died in 1993, under circumstances that remain unclear. Maybe it was a suicide. Maybe a small, vibrating battery was involved.

How did Alibek morally rationalise his work? Using the standard line: Biopreparat was doing the same thing the Americans were doing. It was the USSR’s version of the missile gap argument: if we don’t develop bioweapons, they will first.

Was this ever true? Maybe at one stage. Research efforts between the US and the USSR dovetail perfectly between 1945 and 1969: the same agents, the same aerosols, and the same processes were used on both sides of the Iron Curtain. This likely wasn’t an accident. Classified US research papers on bacteriological weapons had a curious way of ending up in Moscow.

But by 1969, the US was losing interest in the field. Public discontent with the Vietnam war soon expanded to encompass chemical and biological warfare, and facilities throughout the country were picketed. Nixon was convinced by his advisors that disease-based weapons lacked tactical value, and later that year, he appointed a panel that killed America’s biowarfare program. The United States was publically throwing in the towel.

The Soviets, of course, regarded all of this as theater.

“We didn’t believe a word of Nixon’s announcement. Even though the massive U.S. biological munitions stockpile was ordered to be destroyed, and some twenty-two hundred researchers and technicians lost their jobs, we thought the Americans were only wrapping a thicker cloak around their activities.”

But in 1991, the old regime ended, and Alibek was chosen to be part of a group of Russian scientists to tour biological research facilities in the United States. He was shocked at what he didn’t find: Biopreparat had two thousand specialists in anthrax. The Americans had two. The American research papers he saw were all decades old. Supposedly top-secret installations like Fort Detrick were either defunct or converted to into hum-drum civilian medical research. He turned over every stone he could, but there was nothing incriminating to be seen.

But his superiors weren’t interested in hearing that America had abandoned biowarfare, because that would destroy Biopreparat’s raison d’etre and put all of them out of a job. Parallels to the US’s 2003 invasion of Iraq war come to mind. From Bush’s perspective, Iraq had to be guilty of something. After all, he’d already gone to the trouble of invading them.

The hollowness of his mission weighs on Alibek during this period, and thoughts of defection enter his head. Spurring him on is the new wave of racial tension that followed the collapse of the USSR – another thing that interested me. Alibek is ethnically a Kazakh, and his face looks just as Asiatic as it does Caucasian. Until this point, he’d been a citizen of the Soviet Union. Now, he was a foreigner with strange features. This was interesting to me: maybe the union of satellite states across Russia effectively erased a number of racial barriers? Either way, Alibek couldn’t rely on Soviet national unity to protect himself any longer. So he runs.

Alibek escaped his former country, but he can’t escape his place in history: one that’s already pockmarked with smallpox scars, lacerated with varicella-zoster rashes. If a few metaphorical butterfly wingflaps had occurred, a massive breakthrough might have occurred at Biopreparat that greatly altered the balance of power between the USSR and the USA. Or perhaps the breakthrough would have insured that the balance of power became irrelevant, welding mankind into one: carriers for a deadly superplague.

Archimedes spoke about how a perfectly positioned lever could move the world. Disease is a perfectly positioned lever that could end the world. Alibek’s work might have value, if it helps us understand and prepare against the next time Pandora’s box is opened. Because that’s the only certainty: that there will be a next time.

No Comments »