Rotten.com was a website that collected pictures of dead people. As old as the internet, it survived lawsuits, DDOS attacks, and being featured on the Howard Stern show. In 2017, it finally went offline. The website that harvested death became death. If it was a human body, it would have decayed to bones by now.

Imagine a website, Botten.com, that collects pictures of dead websites. It wouldn’t be exciting: just screenshots of 404 and ERR_NAME_NOT_RESOLVED messages. Dead people rot; dead websites cease to exist. At least it’s not the other way around. I’m glad my body will hang around as a foul-smelling mass instead of vanishing peacefully into the ether. No matter how unloved and ignored I was in life, someday it’ll end, and then someone – if only the county medical examiner – will pay attention to me.

Rotten.com had a FAQ page, and one of the questions was “are they real”? They, meaning the pictures. As if car crash victims are like freakish Bigfoot sightings instead of something that could happen to any of us this afternoon.

The webmaster’s reply was characteristically blunt. “Pictures of this nature aren’t particularly rare; they are merely hidden from the public in most cases.”

Hidden by whom? Traditionally, the media and the government stopped you from seeing upsetting photos. It used to be easy (and common) for a state actor to control and prohibit the release of a photograph, and there are photos that we know exist and which we’ll never see. Diana, Princess of Wales, shattered like a bisque doll against the asphalt of a Parisian tunnel. Rudolf Hess, post mortem after what was either suicide or extrajudicial execution by MI6 agents at Spandau Prison. Photos can die, but they can also be imprisoned and serve life sentences.

In 2020, social media is the primary way people view images, and the volume of digital data overwhelms traditional state censorship. 95 million photos are shared on Instagram every minute. Far more than anyone wants to look at. When you scroll a feed, you’re rolling the dice that the next picture won’t be of an amputated penis.

Hiding atrocities now falls to contractors for Facebook and Twitter, typically located in the Philippines or India. These business process outsourcing (BPO) companies provide human content moderation at scale for large companies. They’re the thin brown line separating Facebook from 4chan. Scrolling social media all day might not seem like an especially demanding job, but apparently the job causes psychological problems.

“The despair and darkness of people will get to you”

In his first few weeks on the job, Rahul felt shocked by the graphic videos he encountered of car crashes and child abuse. Eventually, he grew desensitized.

“It gets to a point where you can eat your lunch while watching a video of someone dying. … But at the end of the day, you still have to be human.” Rahul said he didn’t see a therapist — it wouldn’t have been useful to him, he said.

[…]

…it was a graphic video of a child being abused that stuck with him. After seeing the video, he began to notice a change in his own behavior that worried him. “I am not a bad person,” he told Rest of World. “But I’d find myself doing little diabolical things, saying things I would regret. Thinking things I didn’t want to.”

This reminds me of a six year old article from Wired, outlining the same problem.

Eight years after the fact, Jake Swearingen can still recall the video that made him quit. He was 24 years old and between jobs in the Bay Area when he got a gig as a moderator for a then-new startup called VideoEgg. Three days in, a video of an apparent beheading came across his queue.

“Oh fuck! I’ve got a beheading!” he blurted out. A slightly older colleague in a black hoodie casually turned around in his chair. “Oh,” he said, “which one?” At that moment Swearingen decided he did not want to become a connoisseur of beheading videos. “I didn’t want to look back and say I became so blasé to watching people have these really horrible things happen to them that I’m ironic or jokey about it,” says Swearingen, now the social media editor at Atlantic Media. (Swearingen was also an intern at WIRED in 2007.)w of humanity.”

Some content moderators end up traumatized by their experiences, and some are now suing the the companies they used to work for. Others (like Swearingen) have the opposite problem: they’re not traumatized. Quite the reverse: looking at horrible things is becoming far too comfortable for them.

Is there a solution?

Some people enjoy seeing this content. Or are stimulated in some way by it. Robert Ripley’s Believe It or Not newspaper column documented the bizarre and unfortunate, and became an American institution. Rotten.com got millions of clicks a month in 1997. In recent years, subreddits like /r/watchpeopledie have replaced them. Whether this is normal or not is up for debate: it’s conceivably useful.

Someone on Hackernews had the idea of outsourcing content moderation to /r/watchpeopledie.

It’s kind of brilliant. There’s clear lines of supply (disturbing pictures + people who like looking at them) and demand (content moderation + boredom alleviation) on both sides. People would do this job for free, or for MTurk-level wages.

I can think of only two problems with this idea

1) Everyone has different triggers. Perhaps I enjoy beheading videos, but am upset about animal abuse. A /r/watchpeopledie user can selectively avoid links containing disturbing content, whereas a content moderator has to view everything.

2) Doing something recreationally doesn’t mean you’ll succeed with it as a job. Game development studio Ion Storm hired level designers who had created mods for Doom and Quake, on the theory that the skill would translate to the work environment. Often, it didn’t. Doing something for fun is a radically different vibe, because you have agency and can choose the shape of your task. At work, the task’s shape is imposed on you by management. It’s not the activity that’s fun, it’s the freedom.

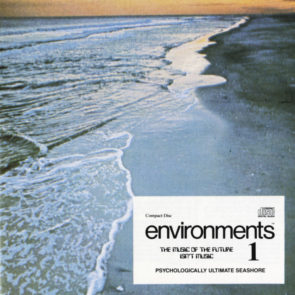

This 1969 LP contains half an hour of beach noises. “This is a joke” would be a reasonable first impression. So would “this was created and should be experienced under the influence of drugs”. After a few minutes, however, the repetitive pounding conjures images: waves curving upwards, rising and then breaking like glass, droplets descending in curtains of diamonds, sand eternally drinking, sea eternally replenishing. The ocean is an breathing lung, and this exact noise has happened over and over for as long as liquid water has existed on the planet. The LP is thirty minutes containing four point four billion years.

Listen long enough, and you start hallucinating. Your Broca and Wernicke’s areas start mistaking the crashing waves for vowels and consonents, as if the sea is speaking as well as breathing. At one point, a low, droning hum (a foghorn?) emerges through the sound of waves. It almost seems to drill through them, like an ice augur. The foghorn tells a story of man appearing and gaining ascendance over nature: but then the foghorn vanishes, and the waves remain.

Environments 1 was the work of a fascinating person from the 60s counterculture: Irving Solomon Teibel. He seems to have been somewhere between a musician, an inventor, and a con artist.

To rip the band-aid off, Environments is not what it appears. This is not the sound of nature. It’s the sound of a computer. It’s not a natural beach. It’s eight minutes of tape hacked up with a razorblade, reassembled in certain patterns, and supplemented with synthetic white noise. It contains an “ocean” to the extent that an Ashlee Simpson album contains “singing.” That it sounds like the real thing is largely because your brain was primed to expect it, and never questions that assumption.

One of Teibel’s interests was psychoacoustics: the impact of audio on humans. Although waves have existed eternally, our perception of them is highly personal, and lives and dies with us. Some people put on a fan to help them sleep, others need to turn a fan off. Stephen King writes to loud rock music, whereas I can’t write to a radio half a block away.

The potential for audio to be used as a tool of relaxation or therapy was a topic of interest in the late 60s, and in that spirit, Teibel decided to record the ocean. Using a Uher portable stereo reel-to-reel tape recorder, he recorded tapes of beaches all across the eastern seaboard of the United States of America, seeking the noises he heard in his head. His attempts failed: for whatever reason, real-life beaches didn’t sound right on tape. The missing link was neuropsychologist called Louis Gerstman, who had access to an IBM 360 at a time when mainframe computers cost around two million dollars. He and Teibel laboriously altered the tapes until they had arrived at a “right” sounding ocean that was, in fact, heavily artificial.

With this knowledge in mind, it’s easy to see where Teibel’s ocean was changed, and why. The “sentence-like” quality of the waves is deliberate: the creator wanted to evoke a language. The way they stay at precisely the same volume throughout is another choice. By the way, I’ve heard rumors that the droning noises aren’t foghorns, but Irv Teibel’s mouth.

“Listen to a computerized beach for an hour” was a rough sell, so Teibel worked over his product with consummate salesmanship. It was sold as a restfulness enhancer, and the cover plastered with exuberant testimonials (“HAVEN’T FELT SO GOOD SINCE MY VACATION”; “cured my insomnia!”; “BETTER THAN A TRANQUILIZER,”; “fantastic for making love!”) that were almost certainly written by Teibel himself.

It worked. The record was picked up for distribution by Atlantic, and it was soon selling thousands of copies. He presaged Brian Eno’s Ambient 1: Music for Airports by a full nine years, but despite this he isn’t remembered as a pioneer of ambient music. Teibel had a similar problem to Delia Derbyshire (who created the electronic Dr Who theme) – you don’t want to invent something too early, or you won’t be part of the seminal “scene” and everyone will forget to credit your innovations.

Psychologically Ultimate Seashore was side A of Environments. The reverse contains Optimum Aviary, which is just a curio. I don’t like the sound of birds, nor the shrill and irritating recording.

And apparently the seashore still wasn’t psychologically optimum enough, because the CD re-release of the 1969 vinyl contains several more changes. It’s doubled in length by (you can hear a clumsy cut where this happens), and has been equalized to take advantage of the flat response digital audio offers. A weird little joke (Teibel recording himself saying “skoosh!” or something) is excised. The LP is a remix of the ocean, the CD is a remix of a remix. Many more Environments were released after this (featuring bells, owls, thunderstorms, and more), but the first is the most famous.

Teibel described his work as “more real than real,” which raises the question: is that a contradiction of terms? Can something be realer than real? If reality isn’t to our liking, can we improve it, or does that mean it’s no longer reality?

As a child, I found a pebble at a beach that was nearly a perfect cube, as if cut with a chisel. It was a naturally-occurring rock (as far as I can tell), but it didn’t look “real” to my eye. I could have changed its shape, smashing off its corners so that it resembled other pebbles…would this have brought it closer to nature, or farther away? It’s an interesting philosophical question.

Another Teibel LP (perhaps his second most famous, after Environments) is The Altered Nixon Speech. It contains Richard Nixon’s August 15, 1973 speech, creatively edited so that he’s confessing to the Watergate break-ins instead of denying them. “My effort throughout has been burglary and bugging of party headquarters, obstructing justice, harassing individuals, and compromising those agencies of government that should be above politics.”

The recording was made in a spirit of fun – Teibel wasn’t trying to hoax anyone – but it’s an interesting “reality improvement”, from Teibel’s perspective. As a NYC-dwelling hippie of Jewish descent, he probably voted Democrat and viewed Nixon as a crook. He probably also saw his “fake” Nixon speech as closer to the truth than the one Nixon actually gave.

Computers are cheaper than they were in 1969, and although Teibel was one of the first digital tinkerers with the truth, he wasn’t the last. Farms of online trolls are forging videos to sway elections. Thousands of rappers are time-aligning and pitch-correcting their voices for Soundcloud likes. Millions of young women use Facetune to make their bodies thinner. In the accelerated evolution of digital media, it’s easy for a new reality to supplant an old one. Not everyone shares Teibel’s essentially prosocial outlook, or his sense of fun. Can we gild the lily? Should we?

Maybe the waves really are speaking. “We are not the sea.“

Let’s read a book together: Faucault’s histoire de la folie à l’âge classique:

“A book is produced. […] its doubles begin to swarm. Around it and far from it; each reading gives it an impalpable and unique body for an instant; fragments of itself are circulating and are made to stand in for it, are taken to almost entirely contain it, and sometimes serve as a refuge for it; it is doubled with commentaries, those other discourses in which it should finally appear as it is, confessing what it had refused to say, freeing itself from what it had so loudly pretended to be.

(Foucault, cited in Eribon 1991: 124)

…But we aren’t reading “a” book. We’re not reading the same thing and participating in a shared experience. We’re reading two different things: even though the above text might have all the same letters and words.

The thing is, they’re not being read by the same person.

Byron wrote Don Juan in 1819. It had a complicated publication history. Due to concerns over blasphemy and libel the book was released in two editions – a very expensive bound edition without an author’s name, and a very cheap bootleg that was distributed among anarchists.

From an evolutionary perspective this is r/K selection. An author wants his work to survive. They can do this by a) making their work so valuable and precious that it can’t be thrown away b) making it so cheap that it CAN be thrown away (and ends up becoming landfill, outlasting civilisation). Byron seems to have tried both strategies at once.

Were both editions the same book? I’d argue they’re not: the first edition was read by the upper class, and the second by anarchists. The first would have been read in a spirit of transgression: you were doing something naughty and beneath your station. A rich person reading Don Juan is like a rich person picking their nose at the dinner table. An anarchist would have read Don Juan as brutal, well-deserved skewering of Romantic literary conceits: one spark dancing in the all-consuming fire immanentizing the eschaton et cetera next paragraph

I sometimes wonder if there’s any point in writing anything. Any idea more complicated than “I exist” is going to be get misinterpreted by someone, somewhere. Readers are like distorted mirrors: light pours into them and is reflected, corrupted. Although from their perspective, it’s being reflected correctly. No other interpretation is valid except the reader’s. Don Juan is an anarchist anthem. Or it’s a toy for the enemies of the anarchists. It’s somehow both, and neither. It’s intended meaning was probably something else entirely.

Books tend to be used for propaganda. In the antebellum south, slave owners frequently justified using verses from the Bible. But freed slaves also relied on scripture, particularly the slave-freeing narrative of Exodus. “The Bible says” is often a less honest version of “I say”.

But a more fundamental issue is that words are a representation of a message, but not a complete representation. Sentences lack the context present in the author’s mind. The reader has to supply their own context, and they usually attribute the one they personally prefer.

- She said she did not take his money.

- She said she did not take his money.

- She said she did not take his money.

- She said she did not take his money.

- She said she did not take his money.

- She said she did not take his money.

- She said she did not take his money.

- She said she did not take his money.

This is the infamous “eight sentences in one”, where the meaning shifts depending on which word carries the emphasis. Additional permutations can be generated by emphasising multiple words (eg, She said she did not take his money.) None are correct. There’s additional pieces of context (who’s “she”?) that would further modify how the sentence is read.

This suggest that it’s a waste of time to hone and shape your writing. The point is to find the right audience, a group of people who are already attuned to your intended meaning. Early screenings of This is Spinal Tap were reportedly filled with squares who didn’t get the joke, and who thought that Spinal Tap was a real band. Rob Reiner and Christopher Guest clearly thought that the audience would be full of smart people like them, the idiots. The space of the human mind is pretty broad, and it can be hard to accept that you don’t occupy a prestiged position within it.

Have you ever wondered why Nigerian scam emails are always so…obvious? Why don’t they vary their pitch a little – by claiming to be from Senegal, say? This is actually intentional: they’re supposed to be obvious, because they only want gullible people to respond to their emails. Sending out millions of spam emails is the easy part: the hard part is finessing the repliers. You don’t want to spend three weeks talking to a person, only for them to decide you’re ripping them off. If you’re smart enough to notice that all scam emails are from the same country, you’re smart enough to not give a credit card number to a stranger. The scammers have found a way to filter their readers so that only the very, very stupid respond.

I think a true writer would use a similar technique. Somewhere out there is a person who thinks my unintelligible drooling makes sense. The challenge for me is to find that person. If it’s you: hello. Please never leave. You’re all I have.

It might be easier to create a perfect reader than a perfect book. I imagine a sociopath writer by crippling the brains of his reader so that they’re exactly that. It’s lucky that writers seldom become totalitarian dictators. Don’t think that Will Self’s new book is excellent? With the right cocktail of drugs you will. With the right frontal lobe excised, you will. You need the correct motivation. It will be fun.