There’s a behavior pattern called “wound-collecting” where a person takes every slight, insult, and injustice they’ve ever experienced and builds an identity around it. “Look at how much I’ve suffered. Look at how much worse I’ve had it than you.” Their victim status becomes a defining attribute, the thing that makes them special. They can’t let their hurt go: they become huge dragons atop a hoard of pain, admiring their scars, and wishing they had more.

I remember reading a feminist’s blog post, titled (and capitalized) something like “why i hate men”. It was a long list of every bad thing a man had every done to her, ranging from sexual assault to a stranger calling her a rude word on The Bird Site, written with pornographic detail and (to me) barely-disguised relish. It made me feel bad. Are you a person made of scar tissue? Are wounds all you have?

Wound-collecting probably starts in pre-adolescence – infants learn that if they stub a toe, adults will crowd around them, fussing and cooing. They don’t understand operant conditioning, but they know the attention feels nice; sometimes better than the stubbed toe felt bad. Enterprising infants learn that if they scream and cry very loudly they don’t need to stub their toe at all.

One of history’s great wound-collectors is James Frey, whose tearjerking, heart-rending, and false account of drug addiction got him on Oprah (here’s John Dolan taking a bolt-gun to A Million Little Pieces in one of his meanest reviews). Women are generally more prone to wound-collecting, but, as Frey proves, men can do it too. So can children. So can its.

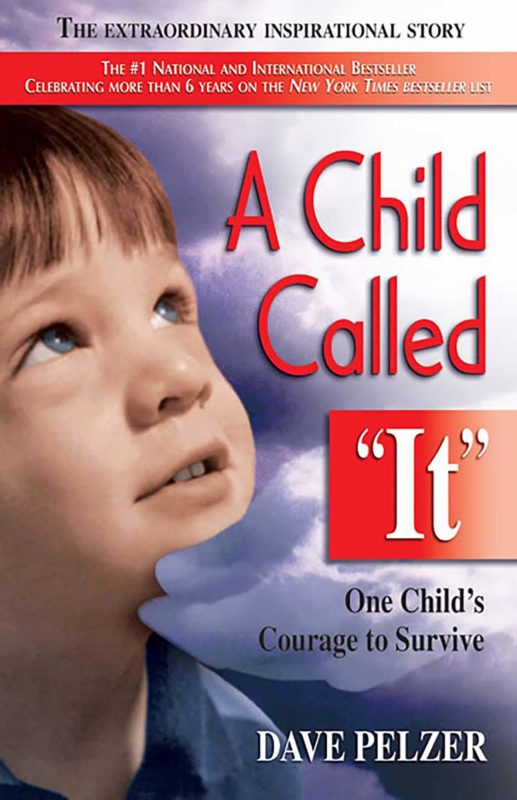

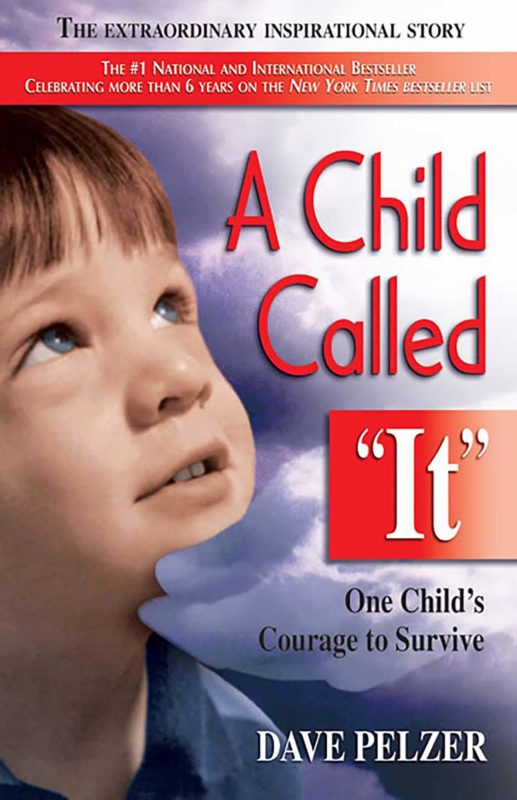

Dave Pelzer was born to an insane alcoholic mother in 1960 and made a ward of the state in 1973. In the intervening twelve-plus years, he experienced what fifth-grade teacher Steven E. Ziegler describes as “the third worse (sic) case of child abuse on record in the entire state of California.” …starved, stabbed, smashed face-first into mirrors, forced to eat the contents of his sibling’s diapers and a spoonful of ammonia, and burned over a gas stove…” I bet he also got the middle seat in the family sedan and was never allowed to choose the pizza toppings. As an adult Pelzer made a career as a rah-rah-you-can-do-it motivational speaker, anchored by the experiences in A Child Called ‘It’. I don’t know to what extent he fits the wound-collector profile. Perhaps he doesn’t at all. But at the very least he’s a wound-displayer, flexing his past like a huge peacock’s tail.

The question is, why is this a viable career path? Pelzer’s motive is obvious: money. But what does the audience get out of it? Catharsis? Thrills?

Pelzer (or his publisher) describes A Child Called ‘It’ as an “inspirational story”. I wasn’t inspired by stories of a boy locked in a garage for ten days without food and suffocated with bleach and clorox, but results may vary. Pelzer’s greeting-card gloop (“I’m so blessed. The challenges of my past have made me immensely strong inside. […] Instead of dwelling on the past, I maintained the same focus that I had taught myself years ago in the garage, knowing the good Lord was always over my shoulder, giving me quiet encouragement and strength when I needed it most.”) is as schmaltzy and fake as a Thomas Kinkade painting. The book – the real book – is marketed with the precision of a laser-guided bomb. It knows its audience of atrocity seekers well, better than they know themselves.

I’ll just say what I think: that lots of people get thrills from reading about child torture, and books like A Child Called ‘It’ are a socially approved outlet for those thrills.

They are socially approved because they’re true. Obviously, if you read fictional child-torture stories you’re a depraved sicko who belongs on every government watchlist at once. But when that same story is repackaged as “motivational lit” or “true crime” or “the daily news”, you can pretend your interest is wholesome (or even virtuous). You’re not scratching a pornographic itch. You’re becoming an Informed Person(tm). You’re learning about The Way The World Really Works(r).

Evangelical Christians waged kulturekampf in the 80s against heavy metal and Dungeons and Dragons while themselves propping up a media industry (Michelle Remembers, Satan Seller, Hell’s Bells, Jack Chick) that was a code-shifted version of the same thing. Michael Warnke sold millions of books with passages like “[the Satanists] took this little girl and they killed her by cutting her sexual organs out while she was still alive, and after she was dead they cut her chest open, took out her heart and cut it up in little pieces and took communion on it,” and Jack Chick distributed hundreds of millions of tracts like “Lisa”, often to the same people who wanted Black Sabbath banned from the airwaves.

Why? Because Black Sabbath lyrics were fiction while Warnke’s Satanism stories were (supposedly) real, offering the reader deniability. Why wouldn’t a concerned parent want to know about human sacrifice happening in the nation’s schools? Prudes and moralists need porn, but more than that, they need excuses.

I say porn with caution. I don’t think that people literally get a sexual thrill from Pelzer’s stories (although who knows for certain?), but there’s an pornlike element to Pelzer all the same. He’s pure object: an archetype, a totem, a lightning rod for anguish, horror, and outrage. Pelzer is an it to his mother and to us: an empty box for the reader’s lizardbrain emotions.

It’s a critical detail, for example, that Pelzer is a child, because this hits the switch on the reader’s maternal/paternal instincts. Nobody would give a shit about a book titled The Senior Citizen Called ‘It’, even though elder abuse happens all the time. People are far more excited when the victim is an adorable little boy.

And the excitement around this book was real and terrifying to witness. In the late 90s people around me were moved to ecstasy by it. “Oh my god, this is awful! That poor boy!”, always spoken in the tones of a junkie sky-high on a twenty dollar bill. On Reddit and Goodreads there are people asking for other books like A Boy Called ‘It’. Horrible book! Traumatized me for years! Please give me more!!! The demand for child abuse lit is insatiable, and although the books are presented as tales of salvation and hope, this is a formality, the same way porn films aren’t really about Mia Malkova’s car breaking down. The point is the suffering. The pain. People want to see it, want to press their blank, awestruck faces against the scars. And when it’s over, they want more. And worse. It’s a hole through the Earth that leads, not to China, but directly out into blackest space.

I haven’t talked about the book at all.

First, it’s not a book, it’s a book-shaped item. It’s poorly written: if Pelzer had relied on prose instead of child abuse he’d be An AutoZone Manager Called ‘It’.

“For awhile Mother banned Father from the house, and the only time we saw him was when we drove to San Francisco to pick up his paycheck. One time, on our way to get the check, we drove through Golden Gate Park. Even though my anger was ever present, I flashed back to the good times when the park meant so much to the whole family. My brothers were also silent that day as we drove through the park. Everybody seemed to sense that somehow the park had lost its glamour, and that things would never be the same again. I think that perhaps my brothers felt the good times were over for them too.”

Grammatical issues aside (“awhile” -> “a while”, singular “time” applied to a recurring event, etc), why is there so much repetition of detail? We’re told he goes to San Francisco to pick up the check, then we’re told again. We’re told he’s at the Golden Gate Park, then we’re told again. Every paragraph in the book is puffed up upon itself, like eggwhites whisked into a mound of empty froth.

The narrative is structured oddly, beginning where it should have ended (with Pelzer’s rescue by Mr Ziegler). A Child Called ‘It’ should have had a thrilling “how will he get out of this?” compulsion, but we already know how he got out. He told us at the start. Pelzer’s imagery is corny and seems right out of a 70s romance novel: rivers of tears go pouring (and/or streaming) down young Pelzer’s face so often that it could almost become a drinking game. His writing sucks all the air out of the room…but could that be an intended effect? To make the book seem rougher, realer, and more believable? The way a guitarist might deliberately biff a note on a record?

Which brings me to the heavily-hinted-at elephant in the room.

The problem with wound-collecting is that a temptation exists to exaggerate or invent wounds; to feather your nest with shards of broken blue glass and call them sapphires. As I read Pelzer’s sad tale a certain feeling came over me – the feeling you get when you’re in a foreign country and your taxi driver says he’s taking you along the scenic route.

Pelzer’s stories individually nudge against believability and cumulatively cross over: I don’t believe that his mother held him beneath freezing water for “hours” (hypothermia would have killed an undernourished ten year old in minutes). I wonder if his lacerations and stabbings left him with scars, and if so, whether they’ve been photographed to provide evidence for his tale (I impaled my finger on a thorn when I was ten and the mark is still there). I also wonder if his mother really spoke like a character in an overwrought Hampstead novel.

“Well, Mr Ziegler says I should be so proud of you for naming the school newspaper. He also claims that you are one of the top pupils in his class. Well, aren’t you special?” Suddenly, her voice turned ice cold and she jabbed her finger at my face and hissed, “Get one thing straight, you little son of a bitch! There is nothing you can do to impress me! Do you understand me? You are a nobody! An It! You are nonexistent! You are a bastard child! I hate you and I wish you were dead! Dead! Do you hear me? Dead!”

I can tolerate dull writing and exploitative subject matter, but I don’t like being conned or taken for a ride. When I learned from Wikipedia that three of Pelzer’s brothers (and his grandmother) have cast doubt on his story, I was unsurprised but still disappointed.

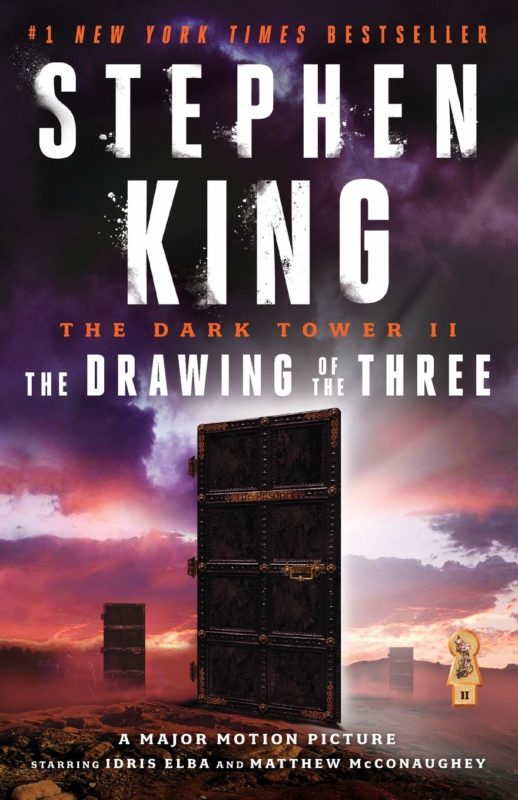

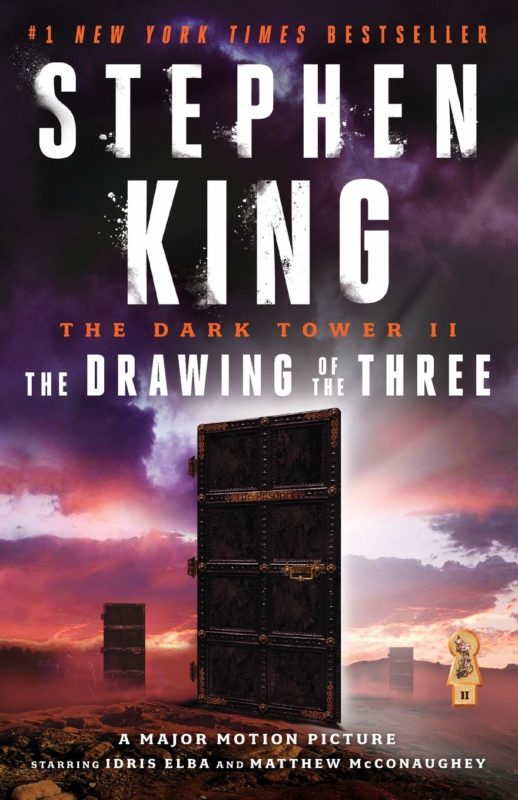

A great book. The best Dark Tower novel? Yes. The best Stephen King novel? Possibly. It has one of his best lines, anyway.

He thought: Very well. I am now a man with no food, with two less fingers and one less toe than I was born with; I am a gunslinger with shells which may not fire; I am sickening from a monster’s bite and have no medicine; I have a day’s water if I’m lucky; I may be able to walk perhaps a dozen miles if I press myself to the last extremity. I am, in short, a man on the edge of everything.

I don’t want to think or write about The Drawing of the Three: I want to re-read it. It’s coked-up and manic, bouncing off the walls like a kid in a small room. The plot moves unbelievably fast – only The Running Man is paced faster, and not by much. It’s ludicrously overstuffed with thrills: later Dark Towers can have a cosy, rambling feel; here the tension drawn so tight that each line seems ready to snap. You can almost cut your finger on the flat side of the page.

It picks up the tale from where The Gunslinger ended it: Roland (the last guardian in a dead or dying world modeled on our romantic image of the Wild West) has just damned his own soul in his quest for the mythic Dark Tower. Alone and friendless, he collapses from exhaustion on a beach, and is attacked (and mutilated) by a monster from the waves. Soon he’s becoming desperately and incurably sick – either his wound is infected, or the monster was venomous. He realizes that he might die before he ever finds the Tower, and attempts a series of “drawings” – rituals bringing other gunslingers (or equivalent gunslingers) from other universes into his world. He hopes they’ll either save his life or fulfill his quest for the Tower after he dies. All he knows about these supposed allies is a shred of biography. There’s a man in thrall of a demon (unknown to Roland) called “Heroin”, a woman who appears to have a split Jekyll-and-Hyde personality, and the personification of death itself.

Roland proves to be just as strong an anti-hero as he was in the book before. The drawings are little more than abductions. He will not take no for an answer, and he has no intention of allowing the proto-gunslingers (who, as chance would have it, all live in 20th century New York) to leave. He has good reasons for doing this – he believes the Tower will soon fall, spelling the end for the last pitiful dregs of creation, unless someone saves it. But it makes him as dark as the tower he’s chasing, and turns him into Clint Eastwood’s Angel Eyes, as menacing as he is heroic.

The Drawing of the Three isn’t perfect. The first third of the book spends a lot of time in Miami Vice territory, featuring cocaine smuggling and DEA agents and cartoonish gangster types: it’s fun but runs a little long. Eddie Dean’s backstory is also overdeveloped considering how uninteresting it turns out to be. The book also features a serial-killer yuppie character that seems ripped off from American Psycho (it’s not – The Drawing of the Three was published four years earlier): a great idea that King could have done more with. Detta Walker proves herself the book’s most inspired villain by the end, not Jack Mort.

But there are far more things that work. Huge swathes of the book are just “a guy walking alongside a beach”. Instead of dead zones in the plot, these become fraught with tension thanks to the ticking clock of Roland’s sickness (which also allow King to explore Roland’s backstory through fevered hallucinations of life before the world apocalyptically “moved on”). Roland was an almost unbelievably good gunfighter in the first book, effortlessly gunning down dozens of people, so King makes the few shootouts interesting by giving him unreliable ammunition (Roland unwisely allowed his shells to become wet by sleeping in wet sand, and many of the bullets he chambers in his revolvers misfire). This is great, effective storytelling, killing lots of birds with very few stones.

And there are hilarious moments too, particularly the parts where Roland (a man from another world who is as much an Arthurian knight as he is The Man With No Name): has to interact with foul-mouthed New Yorkers. This was a big part of what sunk the later books for me: it killed the atmosphere of King’s Lovecraftian Western “Mid-World” to have characters name-dropping Hollywood movies and baseball teams every few pages. But here, the lightness serves a purpose, cutting the dread to manageable levels, like the baby powder in Eddie’s heroin.

‘Well,’ Eddie said, ‘what was behind Door Number One wasn’t so hot, and what was behind Door Number Two was even worse, so now, instead of quitting like sane people, we’re going to go right on ahead and check out Door Number Three. The way things have been going, I think it’s likely to be something like Godzilla or Ghidra the Three-Headed Monster, but I’m an optimist. I’m still hoping for the stainless steel cookware.”

The Dark Tower, at its core, was King’s merging a Lord of the Rings-type epic fantasy quest with genre conceits of a Leone/Sturges/Peckinpah Western. The concept went off the rails for various reasons worth explaining at length, but it’s interesting that the best book in the series had the least time for leather-slapping cowboy cliches. The Drawing of the Three has no cattle rustlers, no dusty red canyons, no bars with batwing doors, one Mexican standoff, certainly no war-whooping Injuns or sniggering bandidos. Instead it’s a fantasy-horror story of a man and his magic, going to other worlds.

King often does his best work with very sparse plots. I’ve heard it said that videogames work not by letting you do things but by not letting you do things (Super Mario Bros would be no fun if Mario could fly, for example), and King has a similar property: he gains strength under restrictions. You can tell the story of Misery, Gerald’s Game, The Shining, in a single, reasonably short sentence. But just as very good sketches can suggest more detail than a photorealistic drawing, King’s threadbare stories never fail to gain largeness and life.

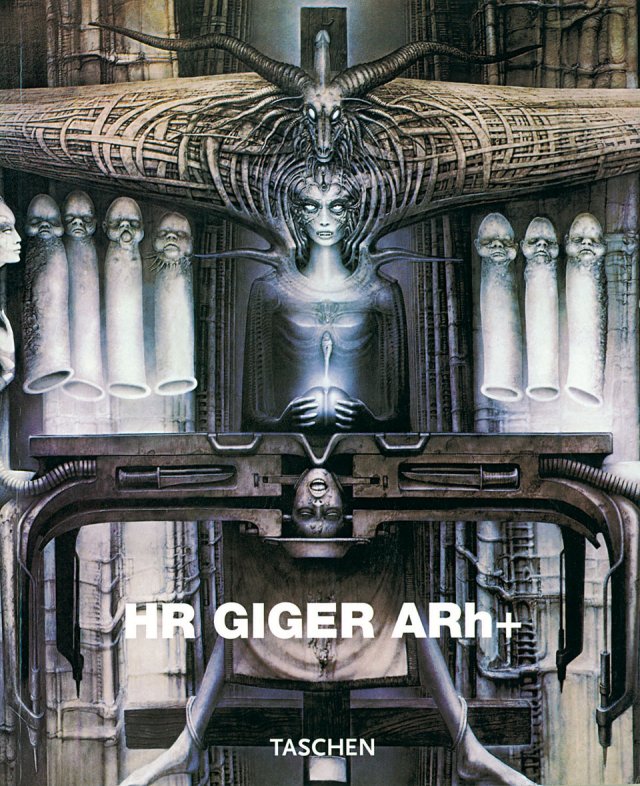

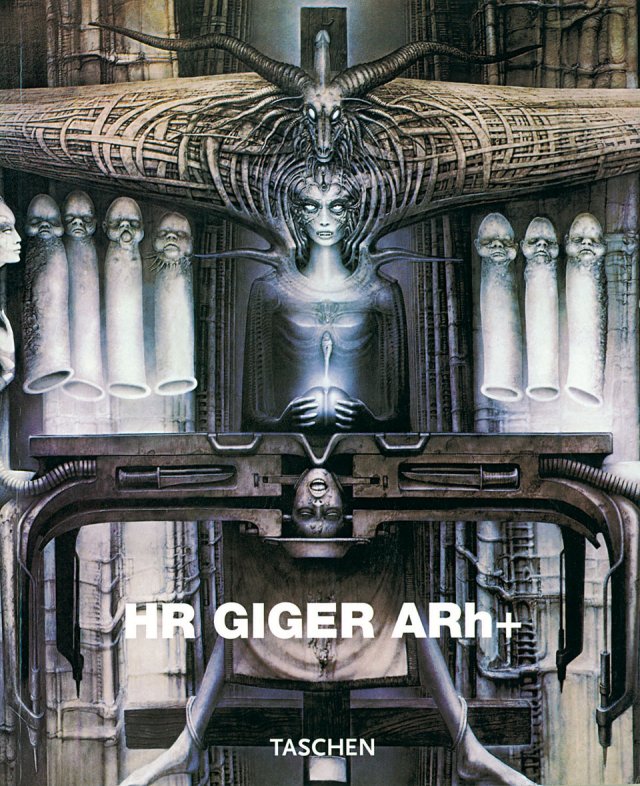

This Taschen artbook explores the work of Hans-Ruedi Giger, who died not long ago. It’s fairly large (23cm*30cm), the print quality is fine, the binding in my copy was falling apart, and Timothy Leary’s foreword is scarier than the actual book. “[Giger] has obviously activated circuits of his brain that govern the unicellular politics within our bodies, our botanical technologies, our aminoacid machines” etc. Yikes.

Why Giger? He was special. Like Hieronymous Bosch, William Blake, and Junji Ito, he saw worlds that nobody else could see. He worked in a lot of mediums but is most famous for his airbrushed “biomechanicals”: totemic, terrifying creatures with dripping teeth, corrugated hides, and electrophosphorescent eyes. They’re an impossible mixture of life and not-life, future and past, sterility and dirt; ancient Egyptian gods built on a Soviet assembly line. There’s little else like them: no artist has ever copied Giger’s signature style with much fidelity. You might say that biomechanicals are more commonly found in reality than in art.

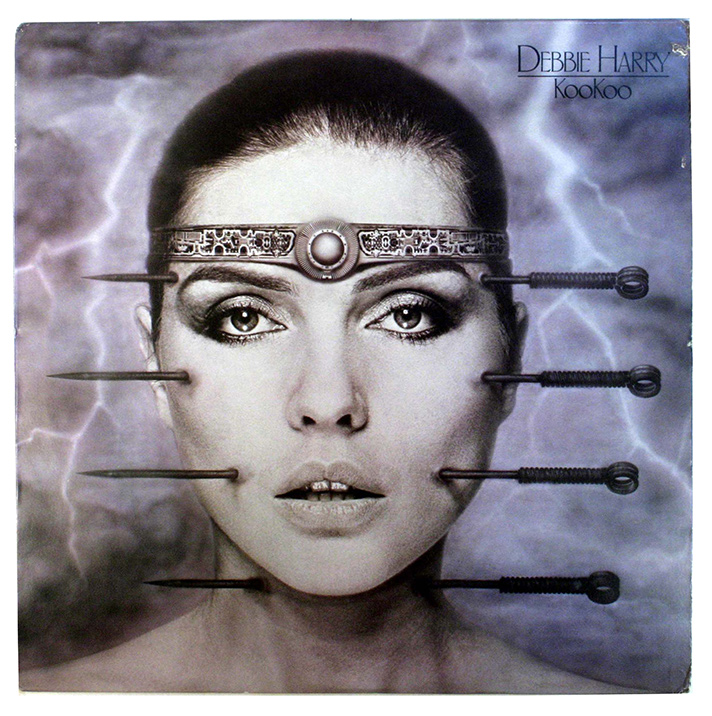

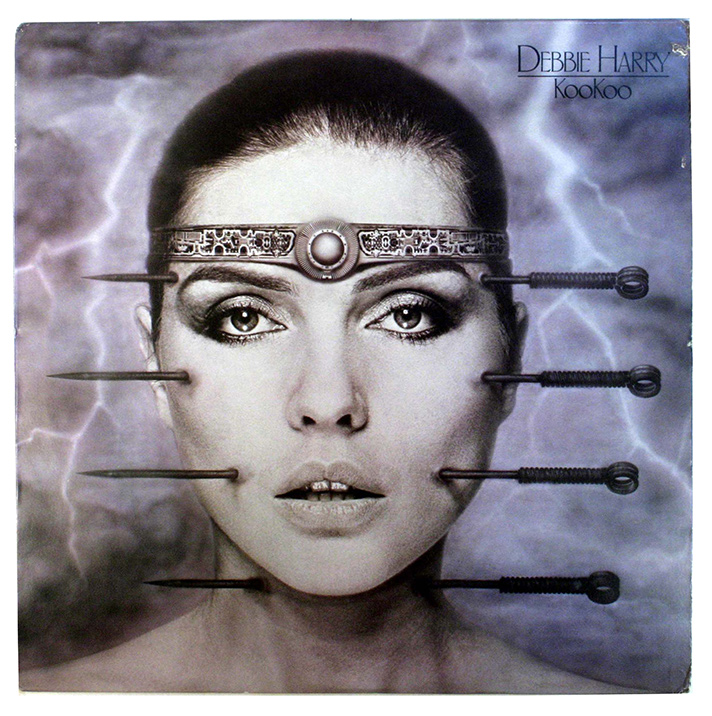

Despite some avant-garde leanings, he was a commercial artist through and through – even after “Giger-mania” took hold in the 70s he wasn’t above decorating heavy metal sleeves, or PC game box art, or guitars, or mic stands, or lager bars. His art showed you unexpected things, and could also be found in unexpected places.

Metal was one of Giger’s favorite subjects. So was flesh, and the ways one can be enhanced or diminished by the other. In the typical Giger image pipes coil and mutate, becoming snakes and phalluses, and glistening shafts and struts pierce necrotic blue-black skin. Giger didn’t predict the future. He grew up in an age of titanium hips, electrical pacemakers, and so on: men have altered their bodies through mechanical means for a long time. Giger’s insight was to tease out the aesthetic power of this union. His creepy-crawly arc-welds of the biologic to the anodic are overwhelming and hit the eye like a bomb. They’re almost too ugly to look at. Or too beautiful. His greatest works actually manage to be both at the same time.

But there’s no sense of gore or mutilation to Giger’s art. He weaves metal through soft tissue and keratin and bone in a way that looks natural, as though evolution rather than surgery produced his creatures. There’s also no motion: Giger’s art has a stillness that’s striking: the “biomechanics” don’t even seem capable of movement. The creature he designed for Ridley Scott’s Alien became a horror movie monster that scampers and leaps around, but there’s none of that in his original artwork, no impression that it might be ready to impale a blood funnel into your chest. It looks petrified in place, a stone god of a stone universe. An advantage of fantasy is that you can create a world that plays to your strengths as an artist, and though Giger never had much talent for evoking movement, he could imagine a place were movement doesn’t happen. His creations are like heavy machines in a factory: bolted into the floor and never moved again. They look perfectly at ease within the environments he creates for them.

The autobiographical text – written by Giger – proves less interesting than the pictures. He doesn’t want to talk about himself, which I submit is a disadvantage when writing an autobiography. He grew up in 1940s Graubünden, lived a childhood so uneventful it’s a miracle he didn’t perish from boredom, worked in advertising, and so on. His father wanted him to become a pharmacist, but he had a dream, maaan. Giger focuses on the dullest details possible, and we never really understand what formed him as an artist. This continues in later passages, where he relates his rise to fame (which reached its peak in 1979, when Alien won him an Oscar for Best Achievement in Visual Effects). Occasionally there are oblique suggestions of personal trouble. “…after the PR commotion and stress”…what stress? “My inner despondency…” What despondency? Giger’s biography fails a basic test: it’s less vivid and informative than reading his own Wikipedia article.

I know someone who attended a Pink Floyd exhibit in Milan – one clearly curated by Roger Waters or someone, because it whitewashed away any controversy, reimagining Pink Floyd as a band of great mates who got on a treat and made awesome music together. The problem (aside from dishonesty) is that the Pink Floyd story is incomprehensible if you don’t talk about the bad stuff – Syd’s mental collapse, Waters’ disillusionment, the destructive infighting. A naif would be left standing underneath a huge sign saying “PINK FLOYD IS BACK!” and wondering “where did they go? And why are there now three people in the band photo instead of four?” Giger’s account of his own life was is a little like that. Things were clearly being left unsaid, which is a shame. I suppose the pictures are the important thing, but they needn’t be the only thing.

The Giger style lives on after him, even though he’s the only one who could really do it. Otherwordly or alien is a common adjective used to describe it, but it’s a specific cold-blooded alien aesthetic. I used to read popular astronomy books which would talk about how moons such as Europa and Enceladus might have liquid oceans, and there would always be the suggestion that we might find fish living there. This is unlikely: life requires a source of free energy, and there’s almost none in such systems. If anything did live, it would be very slow, very conservative of motion. It might communicate and reproduce through radio photons. It would shift fractions of an inch per millenia. If it could think, it would regard motion the way we regard time travel – as an absurd theoretical conceit.

In other words, they might look like HR Giger’s half-frozen monsters. Very cold. Very old. Shunning movement. Giger was the god of the formaldehyde-filled vein, the unbeating stone heart, the liquid nitrogen-cooled brain, and this book cryo-preserves a lot of his unique genius.