On August 15, 1945, a Japanese schoolboy heard the voice of god crackling from a transistor radio.

“We have ordered our government to communicate to the governments of the United States, Great Britain, China and the Soviet Union that our empire accepts the provisions of their joint declaration…”

The Surrender Speech was the first time the Showa Emperor had ever spoken to the common people, and it destroyed young Kenzaburo Oe’s faith. He’d thought that God-Emperor was… a god. He’d had dreams of a massive bird, soaring over Japan like a protecting shield, pinfeathers tearing through the sky like blades. To hear the Emperor speak in a man’s voice (which his schoolmates could mockingly imitate) took a hammer to his spirit.

Occupation soldiers rolled into Oe’s mountain village later that year. He expected the Americans to slaughter them all; instead they gave the villagers candy bars. This seemed incomprehensibly cruel to Oe. He’d expected death; had received disillusion. Everyone had lied to him. The Emperor wasn’t a god, the Americans weren’t devils, and if he was to die for a noble cause, he would first have to find one.

The inner turmoil of this moment colors much/all of Oe’s subsequent writing. Teach Us to Outgrow Our Madness is a collection of four novellas, grappling with a past that has proven to be unreliable.

“Aghwee the Sky Monster” is a surrealist tale similar to Gogol. The narrator becomes the friend of the mononymous “D”, a mad composer who is haunted by the ghost of his son Aghwee (who appears to him as “a fat baby in a white cotton nightgown, big as a kangaroo”). Only D can see this apparition, with whom he conducts nonsensical conversations .

Aghwee is obviously a delusion. Or is he? His existence controls and shapes D’s behavior in the same way a real baby would (for example, D will avoid dogs because he doesn’t want to startle Aghwee, who’s afraid of them), so does he exist in a phenomenological sense? The narrator probes D’s past, finds deep and unhealed wounds, and even horror. It might be D’s deserved fate to carry Aghwee with him eternally.

Shiiku, or “Prize Stock”, is about a black American pilot who crashes in a remote Japanese village. He is chained up and regarded with a mixture of awe and hillbilly racism. I’ve seen some people online describe this story as “autobiographical”, although it couldn’t be – there were no black pilots in the Pacific Theater. I think Oe’s offering some commentary on Japanese wartime propaganda, which contrasted “enlightened” Japan with the socially backward US. The US had consigned generations of blacks to slavery, a medieval institution that Japan had abolished centuries ago (Japan’s ~20 million Chinese and Javanese “forced laborers” were not regarded as slaves). The IJN conducted so-called “Negro Propaganda Operations” – covert short-wave radio broadcasts attempting to recruit African Americans to the Axis cause. “Prize Stock” is caustic commentary on Japan’s supposed post-racial politics. They were more like Americans than they thought.

“Teach Us to Outgrow Our Madness” is about a fat Japanese father and his disabled son Eeyore (this is another repeated theme of Oe’s, whose own son has severe autism) who have several supernatural adventures. My least favorite story: it reprises themes expressed more eloquently elsewhere.

Then there’s the monolithic “The Day He Himself Shall Wipe My Tears Away”, a long and intricate story that has to be read carefully: there are tricky perspective shifts. In short, it’s about a man who is dying in hospital of a “cancer” that is almost certainly imaginary. Descending into the story is descending into a tangled web, there’s narratives within narratives, lies within lies, houses built on quicksand, quicksand built on quicksand, etc.

It’s like a Fellini movie, none of the facts are that important: they only matter insofar as they illuminate the mental landscape of a profoundly deluded man. He’s arrogant, proud, self-pitying, defensive, and not particularly sympathetic. The lunatic in “Aghwee” is suffering from madness as a form of penance. The hero of “The Day…” wears insanity like protective armor. Apparently this is Oe’s veiled roman-à-clef of Yukio Mishima, author and poet turned right-wing nationalist who had committed seppuku two years previously, following a failed coup attempt.

So all four stories are personal, yet they’re bigger than Oe. He shows the way a person can forcibly have the fabric of a nation threaded into his skin, and the pain of having that fabric torn away. What’s the use of memories? To show us what happened in the past? Or to guide our behavior in the present? The two goals are often incompatible.

It asks questions such as “what’s a nation founded upon?” Sometimes, the answer is “nothing”. Take Algeria. Why does Algeria exist? For no reason. It’s just there. But then you have “proposition” nations, which are founded (or believe themselves founded) upon an ideal or belief. I’d say that the United States, modern-day Israel, and Showa-era Japan fall into this category.

Generally it’s bad to be a proposition nation, because you run the risk of your proposition being proven false. What happens then? What happens if you’re the Independent State of Phlogiston? The Republic of Timecube? You lie, I guess. You deceive your citizens, deceive yourself, because the only other course is ruin. Japan could have never have won the Second World War. It persisted on in denial of this fact. Its soldiers were fighting a hopeless war, and Kenzaburo Oe was being raised to throw himself into a meat grinder. Nobody had any plan to win. The nation just staggered blindly forward, deeper into the disaster, inflicting psychic trauma on its citizens that lasted for years. State-sponsored falsehoods continue in memory long after the state falls to pieces.

After the war ended, Japan spent minimizing its war crimes: writing arrant falsehoods into its history books. Men who had produced mountains of bodies went unpunished and were reassimilated back into society. Oe’s childhood disillusionment could have been worse: he wasn’t told about Nanking or Unit 731. D is burdened by an imaginary baby, the protag of “Day” is burdened by an imaginary cancer, and Japan was burdened by an imaginary history. Even in the 70s there were men like Mishima, who literally killed himself in service of the false god.

Oe achieved fame in Japan due to work like Teach Us to Outgrow Our Madness, but it’s easier to forgive than to forget. In 1994, he was named to receive Japan’s Order of Culture. When he learned that he would receive the Order from the Emperor’s hand, he refused.

The German language has two words for silence. Stille means there is silence. Schweigen means something is silent. The change of meaning is subtle yet important: schweigen suggests that the silence isn’t incidental: something could make a sound but isn’t. Put another way, stille is meaningless silence, schweigen is meaningful silence.

English lacks this distinction and must modify “silence” into an adverb (see “keep silent” and “remain silent”) to achieve the same nuance. When encountering “silence” in an English translation of German verse I sometimes wonder whether the German contained stille or schweigen.

Purity! Purity! Where are the terrible paths of death,

Of grey stony silence, the rocks of the night

And the peaceless shadows? Radiant sun-abyss.

Sister, when I found you at the lonely clearing

Of the forest, and it was midday and the silence of the animal great;

Whiteness under wild oak, and the thorn bloomed silver.

Enormous dying and the singing flame in the heart.

Darker the waters flow around the beautiful play of fishes.

Hour of mourning, silent vision of the sun;

The soul is a strange shape on earth. Spiritually blueness

Dusks over the pruned forest; and a dark bell rings

Long in the village; peaceful escort.

Silently the myrtle blooms over the white eyelids of the dead one.

Quietly the waters sound in the sinking afternoon

And the wilderness on the bank greens more darkly; joy in the rosy wind;

The brother’s soft song by the evening hill.

Georg Trakl (3 February 1887 – 3 November 1914) loved silence, particularly schweigen. The theme of quietness – deliberate quietness – makes his poems pulse and glow. “Springtime of the Soul” (Frühling der Seele) has three “silences”. The first and second (the animal, and the sun) are schweigen. To Trakl everything can conceivably have a voice. The third silence (the myrtle) is stille, which is actually unusual for Trakl – he often uses schweigen in reference to plants, too. He revered nature, and seemed to view it without the distinctions (sapient/stupid, ambulatory/stationary, alive/dead) that others imposed. To Trakl, it’s easy to imagine a plant talking, or the sun talking. His poems describe nature’s myriad forms as the folds and nodules of a single great throat, pouring out sound or silence.

Trakl died young after living a terrible life. His poems are fragile and often hurtful to read: they actually seem bruised, like flower petals crushed by the pressure of a thumb.

Something about his brain was abnormal. Dr Hans Asperger analyzed Trakl’s writings and declared him an exemplary case of the recently-discovered syndrome which bears his name. Trakl’s poems reflect a very intense relationship with topic matter: read a few Trakl poems and you’ll see him repeating ideas and subjects obsessively – trees, plants, pastoral settings, animals in forest glades, his sister (giving rise to unfortunate rumors about an incestual relationship between the two) – which is a hallmark of autistic “special interests”.

The sensoriality of Trakl’s poems is also remarkable, the way everything is chained to a description of a color or sound. In the above poem you can see how he keeps coloring things that don’t have color – eg, souls are blue, the wind is rosy. It’s possible he had synaesthesia, and experienced the world in a sensorally conjoined way that others didn’t.

Either way, there’s a childlike quality to his verse – in a positive sense. It uses simple words and simple ideas, but they hit hard, particularly the oblique yet awful passages alluding to war. Whenever man-made sound intrudes into a Trakl poem, it’s never good. “Trumpets” is short but memorable: reaching thunderstorm-like intensity that nearly equals Poe’s “The Bells”.

Under the trimmed willows, where brown children are playing

And leaves tumbling, the trumpets blow. A quaking of cemeteries.

Banners of scarlet rattle through a sadness of maple trees,

Riders along rye-fields, empty mills. Or shepherds sing during the night, and stags step delicately

Into the circle of their fire, the grove’s sorrow immensely old,

Dancing, they loom up from one black wall;

Banners of scarlet, laughter, insanity, trumpets.

Trakl’s work is easy to memorize, particularly upon repeated readings – which you’ll have to do, because his collected work is scant. Like the modernists and romantics he took inspiration from (Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Verlaine), he died long before his time. In World War I, he served as a medical officer, and had scant opportunity to experience either stille or schweigen. After the Battle of Grodek in 1914, he was given a barn full of ninety badly wounded soldiers, and told to care for them. He couldn’t cope, tried to shoot himself. For this he was sent to a military hospital in Cracow. He assumed he was going there as a medical officer. Instead, it as a convalescent. What’s that old joke about how doctors wear lab coats so you can distinguish them from their patients?

Whatever treatment he received didn’t work: his depression was deep and total. Eventually, he tried to kill himself a second time – this time with a cocaine overdose – and was successful. Another man consumed by mechanical violence. There’s something cruelly arbitrary about Trakl’s death – the Great War caused a lot of fathers to bury their sons, but at least most of the deaths have a kind of planned badness – a general decided it was worth the lives of x many soldiers for y tactical salient, or whatever. Trakl didn’t even get the dubious honor of being cannon fodder. His death was completely and finally meaningless – just a cruel incidental byproduct, serving no purpose except to return schweigen to his sound and image filled head. The war robbed a man of his life and the world of the poems he could have written. Here’s one last -“Grodek”.

At evening the woods of autumn are full of the sound

Of the weapons of death, golden fields

And blue lakes, over which the darkening sun

Rolls down; night gathers in

Dying recruits, the animal cries

Of their burst mouths.

Yet a red cloud, in which a furious god,

The spilled blood itself, has its home, silently

Gathers, a moonlike coolness in the willow bottoms;

All the roads spread out into the black mold.

Under the gold branches of the night and stars

The sister’s shadow falters through the diminishing grove,

To greet the ghosts of the heroes, bleeding heads;

And from the reeds the sound of the dark flutes of autumn rises.

O prouder grief! you bronze altars,

The hot flame of the spirit is fed today by a more monstrous pain,

The unborn grandchildren.

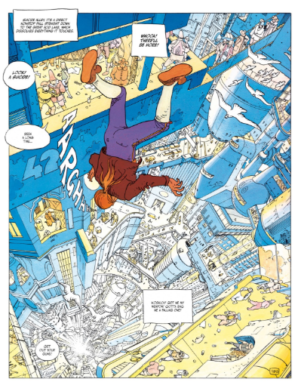

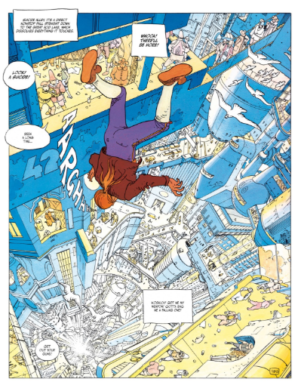

The greatest comic of all time, according to some. This is a small exaggeration. After exhausting, grueling, and – dare I say it – faintly erotic analysis, I bring you the truth. It’s the greatest comic of its first week of issuance in 1980. Perhaps the weekend after, too. Best I can do.

The story is complete rubbish: The Incal has a “toddler smashing action figures together” plot where the MetaBaron battles the HitlerRodents while the GlorpFucks unite the PlotStone with the QuantumMatrix and all seems lost but then the SlamPig Brigade arrives and blows up the NightmareBot and on and on and on (and on and on). Comics like The Incal don’t “end”, they merely stop having new issues produced. The fact that it has six volumes is incidental: it could just as easily have gone on for six more, or sixty more, or until Jodorowsky died.

People describe it as “surrealist” but it’s not, they describe it as “philosophical” but it’s not, etc. Visually it evokes those psychedelic 70s-80s animated movies like Wizards and Fantastic Planet, as well as French “bandes dessinées” comics such as Tintin. It consists of very powerful and imaginative imagery, with the plot noisily emitting a dense cloud of complications. It also reminds of Metal Hurlant/Heavy Metal – which it has to, because its artist Mœbius was an important figure in that comic. Some of Mœbius’s famous visual motifs are present in the Incal, such as Arzach’s white pterodactyl, here seen as the hero’s comical sidekick, Deepo.

Arzach is a fearsome beast, and I would recommend it over this comic. It’s short and confusing, but you feel in your bones what it’s trying to do. It stuns and awes the senses with visuals of alien worlds, making characters seen both big and small, and reading it is like drunkenly climbing a ladder to heaven. The absurd visual style (merging prehistory and the far-future) only adds to the grand, hallucinatory effect.

As does the fact that it’s wordless. Some comics gain from having text, others lose. Neil Gaiman once wrote that he “read” some Metal Hurlant comics (not understanding French) and loved them. Later, he read those same stories in English translation and was disappointed – now that he could understand the words, they seemed curiously small. I had a similar experience with certain untranslated Junji Ito manga. It wasn’t that they were bad, but my imagination made them seem much greater than they really were.

The Incal is probably a similar case: more enjoyable if you can’t read the words and only have Moebius’s imagery to guide you. The comic book emerged out of Jodorowsky’s 1975 attempt to adapt Frank Herbert’s Dune. He’d planned a 10-hour opus that would have made Heaven’s Gate look like a poster child for minimalism, featuring HR Giger, Mick Jagger, Salvadore Dali, spiritual and psychedelic themes, etc. He was unable to secure funding for this project (film studios have found more convenient ways to declare Chapter 11 bankruptcy) and much of the work he did was repurposed into The Incal. There’s little evidence of Dune in the final comic, but I doubt Jodorowsky’s planned film would have had much connection to it either.

There’s some cool moments. The in-media-res opening image of sleazy detective John DiFool being flung down “Suicide Alley” is striking and often imitated. The grungy tone of some of the urban scenes might have been an influence on eg, Blade Runner, just as the skulking bounty hunter MetaBaron reads as an early version of Star Wars’ Boba Fett (Fett’s first public appearance predates MetaBaron’s, but I’m fairly sure MetaBaron was conceived of earlier). There’s no shortage of ideas here, some you’ll recognize in later, more famous products. I have no idea to what extent this is conscious “inspiration”. Perhaps Jodorowsky merely put his hands on some ideas that were already circulating in science fiction and gave them form. Most pertinently: the world of The Incal feels slimy and lived-in, the politicians are corrupt, religious figures are hypocritical, everyone’s sex-obsessed and venal. It depicts a lived-in future, perhaps a died-in future. But spiritual purity is possible, no matter how debased you are.

The Incal definitely has flaws, but it also has strengths. It’s a highly charming work, always easy to like. It has a sense of humor – the pangender “Emperoress” got a laugh out of me. Fans of Jodorowsky’s films will probably love this, as it’s full of little echoes of El Topo and The Holy Mountain (the absurdity of Deepo becoming a religious icon is straight out of the latter movie).

But ultimately, it’s just not as clever as it wants to be. It needs writing to match Moebius’s art – either that, or no writing at all. The plot’s just standard science fiction and fantasy stuff that was done better before (and certainly better afterward), and although it’s more intense than the average Bronze Age superhero comic, but still hews to the superhero formula. The story is written to be both collapsible and extendable. It’s made up of details, none of which are essential. If you have too many pages, Trim some details. Conversely, you can extend a story by adding extra details. It’s always apparent that “story” is just a secondary concern to most comics. Their first one is to take up space. Their allegiance is to the space. They have to fill up a certain amount of page area and no more, and this locks them into place like iron bars. Nobody wants to pay for a comic with a blank page. Or half a blank page. Nor will they pay for a comic that ends mid-climax with “sorry, ran out of space! Send me a letter if you want to know the ending!” The story must fit. You’d think that the advent of webcomics would cause artists to break free of these limitations, but most don’t.