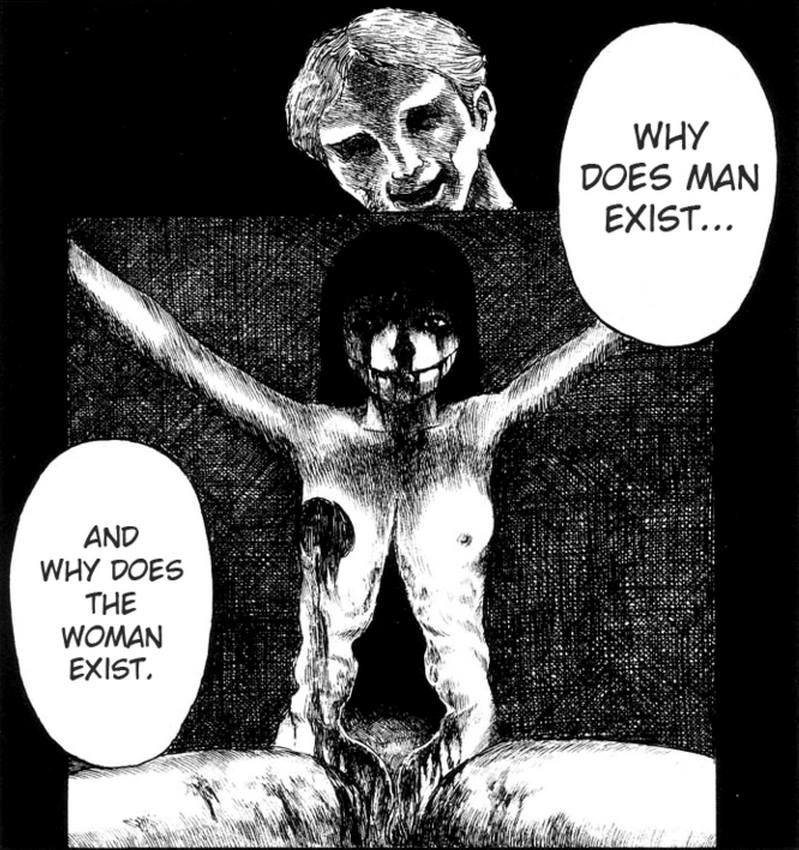

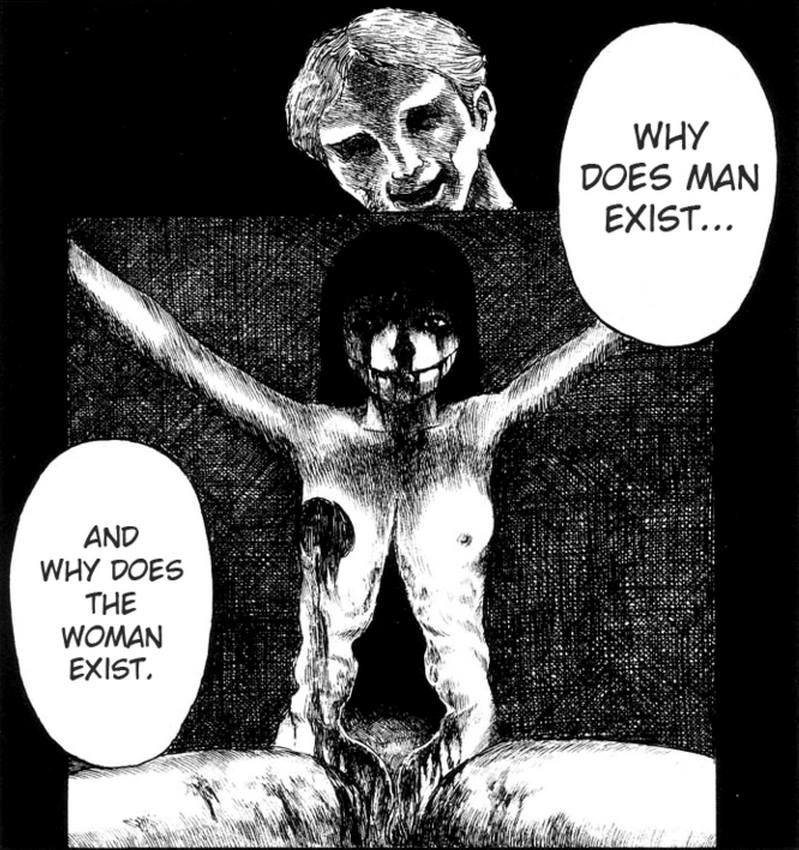

In this movies, a common joke is a schoolboy with a porn magazine hidden behind a textbook. Hell Season is the kind of thing you’d have hidden behind a porn magazine. It is an infamous 10 chapter volume of gore, sex, and unwholesomeness, put together by an all-star lineup of guro artists (Waita Uziga, Shintaro Kago, Machino Henmaru…)

In this movies, a common joke is a schoolboy with a porn magazine hidden behind a textbook. Hell Season is the kind of thing you’d have hidden behind a porn magazine. It is an infamous 10 chapter volume of gore, sex, and unwholesomeness, put together by an all-star lineup of guro artists (Waita Uziga, Shintaro Kago, Machino Henmaru…)

I should warn you that the production values aren’t terribly high. Asuka Shiraishi’s manga doesn’t even look finished – you can see construction lines in his drawings. In some cases the stories are bogged down by poor-quality art, but in some cases they transcend it, as in one notable instance at the end.

Kago’s “When All Is Said And Done” opens the festivities. If you want bleeding rectums, this comic’s got them. Another perennial guro trope – quadruple amputees – makes an appearance, too. All in all, a good story, although it’s not as imaginative as you’d expect from him.

Uziga’s “This Piece of Meat is Talking” comes next. What can I say about Waita Uziga? He’s brutal, and he likes to go for Bambi-like emotional trauma, too. All of his panels contain someone either crying or dying. Unfortunately, his art is a mess…a blizzard of geometric shapes with wonky shading, making it a forensics-like challenge to work out what’s going on. His characters have a very stereotypical “big eyes” anime look to them. I’ve always found it hard to get into guro when I can hear the Sailor Moon theme in my head.

“The Holes” by Machino Henmaru is pleasant for most of its length, and has a mule-kick of a final page that sends it completely over the top. “Rotten Bud” by Mitsuka Hattori has a nostalgic Suehiro Maruo atmosphere that I really enjoyed.

The final few stories are a bit arty and weird. “Mechanical Destructive Killcommand” (try finding a more anime title than that) evokes memories of 80s crap like MD Geist and Genocyber – soldiers fighting a war with a purpose that isn’t clear, with ill-explained weirdness occurring all around them. “Shameless Ranger” is less oblique and a bit more elaborate, but there’s still a jarring sense of having walked into a party halfway through – that we’ve missed out on important events, and that the manga was written to be that way.

Jun Hayami’s “Crowd of Shit-Sacks” (awkward translation, I think) is the true classic from the volume. The art is shit, but the mood Hayami evokes is fascinating, and the atmosphere is extremely bleak. There isn’t that much of a story, it’s more a stream of images describing exempli gratia desolation and abandonment . This one really depressed me when I first read it. Jun Hayami is an amazing talent who got a bit of exposure with Creation Books’ Beauty Labyrinth of Razors – I doubt you can get a copy of that now.

Show this to your mother and she’d cut you out the will, cut you out of the family, and probably cut you in more literal ways. But it’s fun if irredeemable look into the destructive backbrain of one of the world’s more repressed countries.

Horror and science fiction are the two genres that forked away from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. That story contained elements of both, but the forward-thinking optimism of science fiction warred against the regressive atavism of horror, and the styles went their separate ways.

Horror and science fiction are the two genres that forked away from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. That story contained elements of both, but the forward-thinking optimism of science fiction warred against the regressive atavism of horror, and the styles went their separate ways.

Some artists have wondered whether the genres are destined to combine again someday. What if the end product of science is horror? What if our increasing body of scientific knowledge is a Malthusian trap destined to destroy us? Pierre and Marie Curie discovered radium at the turn of the century. They thought they had found something benign and interesting – further developments produced a weapon that blasted 200,000 people to dust. We now live in an age of robotics and genomics – many dice are in the air, and who knows where they’ll land. While we wait, we might get a forewarning in the form of art. Certainly Frankenstein seems to have predicted a few things.

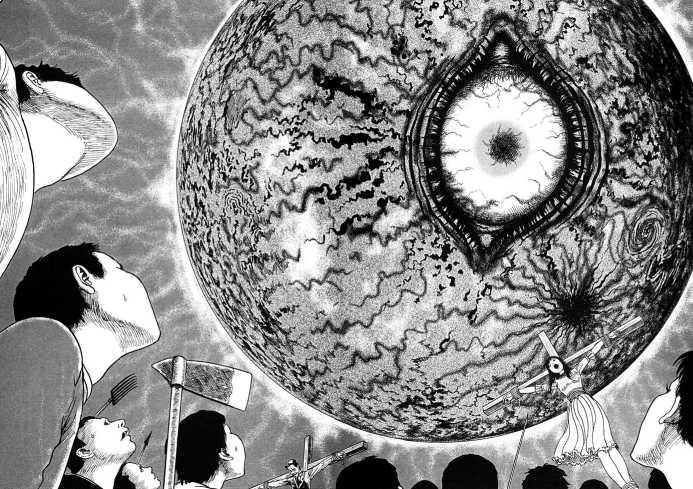

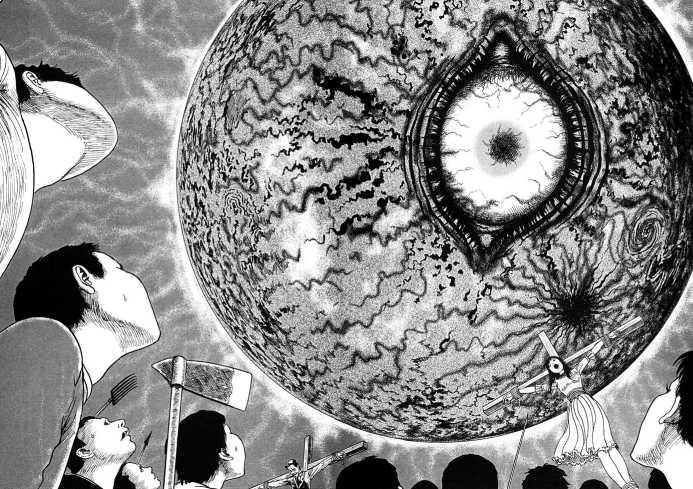

Hellstar Remina is a one-volume manga that Junji Ito created in 2006 that serves as a marriage of science fiction and horror set in a near-future earth. A strange planet has been discovered in the night sky, and it is on collision course with Earth. As panicking mobs tear cities apart, a group of people make a stand against the cosmic darkness filling the sky and the man-made darkness engulfing the the world below.

Remina isn’t as scary as Uzumaki or as revolting as Gyo, but it moves at a blistering pace, and if the story’s developments sometimes don’t make sense, at least you’re not given enough time to think about them. Without exaggerating, as much happens in Remina‘s one volume as happens in Uzumaki‘s three. Impressively, character development isn’t totally perfunctory, with a lot of cultists and greedy industrialists and whatnot. The end of the world means an end to consequences, and Ito documents mankind’s pathology to the full.

Remina is Ito’s most advanced work from an artistic standpoint. Buildings topple like dominoes, blast overpressure waves scatter crowds of people, and tsunamis engulf landscapes. There’s so much complicated and difficult art here, and all of it is rendered in Ito’s signature “organic” style. You’re a little scared to touch this guy’s drawings, his linework seems to be made of squirming bacteria rather than ink.

The bonus story “Army of One” is a welcome addition to the volume. A mysterious lunatic is stitching dead bodies together, and to make it worse. Very spooky and cool. Don’t waste time thinking about the ending – obviously not even Ito knows what it means.

Ito is a fan of sci-fi from way back…I’ve heard that his first creative effort was an abandoned SF novel in the style of Sakyo Komatsu. Hellstar Remina isn’t his best work, but it’s arguably the last 100% good thing he did for his fans, and a crazy ride to remember by any standard. Ito would soon lose his fastball and start creating boring Ray Bradbury ripoffs like Black Paradox. But for now, doomsday looms.

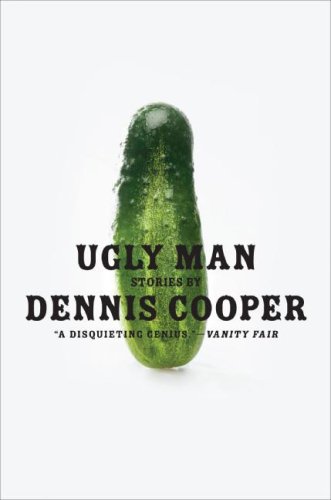

When reading a favoured author I feel a sensation of comfy familiarity – like I’m putting on much-worn, much-loved jacket. I don’t think I’d ever feel that about Dennis Cooper, even if he did become a favoured author. This is a collection of short prose pieces that can’t really be classified at all. The style and format changes constantly. Some pieces are short stories, others take the format of conversations or letters, others are metafictional and are presented via transcribed live performances, etc.

When reading a favoured author I feel a sensation of comfy familiarity – like I’m putting on much-worn, much-loved jacket. I don’t think I’d ever feel that about Dennis Cooper, even if he did become a favoured author. This is a collection of short prose pieces that can’t really be classified at all. The style and format changes constantly. Some pieces are short stories, others take the format of conversations or letters, others are metafictional and are presented via transcribed live performances, etc.

The book ends with an interview with the author and a list of his influences. This reads not as an afterword but as a continuation of the rest of the book. No doubt if he’d included his grocery list, it would also have seemed like a part of the book.

The quality is as unpredictable as the writing, but there are two very good moments in this collection. The first one is “The Guro Artist”, about a pederastic lunatic who kidnaps a boy with “an ass too exquisite to waste its whole life squeezing out shits” and surgically remakes him into a living anime character. It goes for only three pages but is as disturbing and horrible as anything I’ve read.

Following straight after is “The Anal-Retentive Line Editor” a series of letters to a gay erotica writer from a magazine editor from hell (or maybe Sodom). (“…my big dick [Bland, de rigueur. Perhaps ‘gigantic,’ ‘monster,’ ‘humongous’? You could also indicate whether it is circumcised or not. Is the dick leaking seminal fluid? If so, that would add some pizzazz]“). One of the longest things in the book but far and away the funniest.

The other stories I can take or leave. A comparison to Burroughs seems obligatory, but only because of the gay sex – the actual prose is more redolent of authors like Palahniuk. There’s some disquietening stuff in here, but much of it is adulterated with comedy, and your default expression while reading is one of amused horror.

“Ugly Man” is about a man with a debilitating disease that renders him hideous to the eye. He copes by sleeping with lots of male prostitutes. “The Brainiacs” is about a kid deciding to become a terrorist. Being a jihadist on a holy war doesn’t make you immune from being a loser who gets picked on.

The longer works, “Anal-Retentive” aside, are not very interesting. The opening story “Jerk” feels like reading Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho, a basic idea made into a very long tale, and your boredom rises with the body count. “Oliver Twink” is the same. It occupies a ton of pages and doesn’t really pay for its keep. “Three Boys Who Thought Experimental Fiction Was For Pussies” has lots of gay innuendo, but I found it boring.

If you want good, discerning fiction…well, I’m afraid Dennis Cooper doesn’t much care what you want. This collection is what it is. There are no rules, and no limits. Reading it makes me feel like a windcock blown every way but loose.

In this movies, a common joke is a schoolboy with a porn magazine hidden behind a textbook. Hell Season is the kind of thing you’d have hidden behind a porn magazine. It is an infamous 10 chapter volume of gore, sex, and unwholesomeness, put together by an all-star lineup of guro artists (Waita Uziga, Shintaro Kago, Machino Henmaru…)

In this movies, a common joke is a schoolboy with a porn magazine hidden behind a textbook. Hell Season is the kind of thing you’d have hidden behind a porn magazine. It is an infamous 10 chapter volume of gore, sex, and unwholesomeness, put together by an all-star lineup of guro artists (Waita Uziga, Shintaro Kago, Machino Henmaru…)