They say nobody should write books about war. The ones who weren’t there will never understand, and the ones who were there remember everything with the most brilliant hindsight a man can have.

They say nobody should write books about war. The ones who weren’t there will never understand, and the ones who were there remember everything with the most brilliant hindsight a man can have.

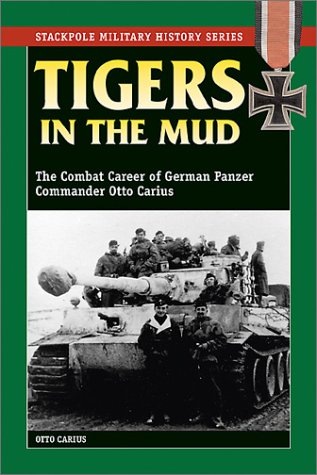

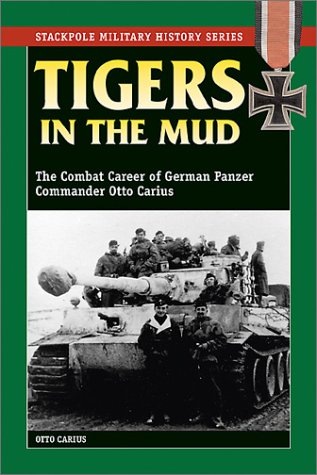

Tigers in the Mud is the combat memoirs of German tank commander Otto Carius. Rejected twice from the Wehrmacht for being underweight, Carius rose to become one of the most deadly men of World War II, credited with over 150 tank kills. He was awarded the Knight’s Cross, to which Himmler would affix the Oak Leaves in 1944. He served on multiple fronts, fighting “Ivan” in the east and then American soldiers crossing the Rhine. This is his story: WWII from behind the 88mm cannon of a Tiger.

Carius describes the legendary Tiger I with something like awe and something like love. They were the German answer to the Russian T34, huge, ugly, but not without some inner grace. Controlling them was easy (“It drove just like a car”, Carius says), and they could make 45kph on a road and 20kph cross-country. They packed massive firepower. Carius describes stunts such as letting an enemy hide behind a house, and then shooting them straight through the house’s walls.

It’s not all about tanks, it’s also about people, and Carius acclaims the men he fought beside (and under). He seems eager to emphasise the patriotism and camaraderie of the Wehrmacht at the front line, and says that nobody was forced into battle. Some men were Nazis, some opponents of Nazis, some motivated by nothing more political than the glory of their homeland.

Some parts are nail-biting, like when a stiff-necked Oberst orders Carius to advance into a deathtrap. Carius ends up shot once in the forearm, four times in the back, and once in the neck at point blank range.

Some parts are downright bizarre. It seems German administration was lax at writing documentation for the Tiger I. The Russians, however, published excellent guides on the Tiger I’s strengths and weaknesses. The result was a surreal process where German tank drivers had to learn about their own tanks using captured enemy literature.

Carius tells in detail of his meeting with Heinrich Himmler, who is described as calm and friendly. Himmler offers Carius a place in the Waffen-SS, which he declines. Then, in another bizarre scene, Himmler asks if Carius has seen the sights of the city, and gives him a car to go joyriding through Salzberg. The war is winding down at this point, and soon Carius tells of less happy things: the grim conditions of American prison camps where, he says, the Yankees set about proving that they were worse than the Germans. A quote stands out: “peace is hell.”

Carius was a gifted soldier but only an average writer, which is better than the alternative. Had he been a gifted writer but an average soldier he likely would have been killed, which poses great difficulties if you want to write a book.

Nevertheless, I wish there was more detail, and more elaboration. There are many amazing things in this book, but alas, we see them only as sketches. One example is found in the book’s early pages. Carius describes a tank tipping over while falling off a ramp. What happened next? How do you get a sixty ton tank back upright? Who’s job was that in the army? How badly damaged was the tank? I wish he had gone a bit deeper into some things. Tigers in the Mud is a fascinating tour through WWII, but it is a rushed one, and gunsmoke sometimes obscures the view.

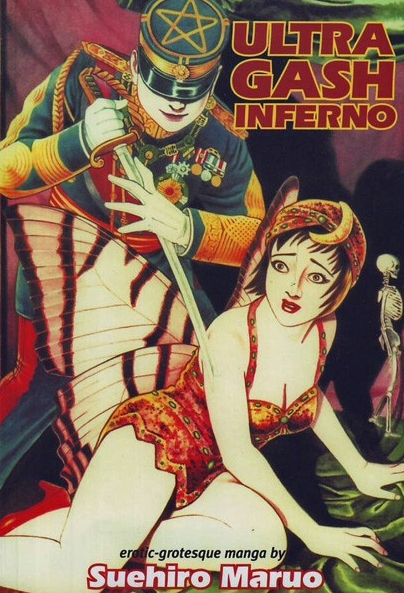

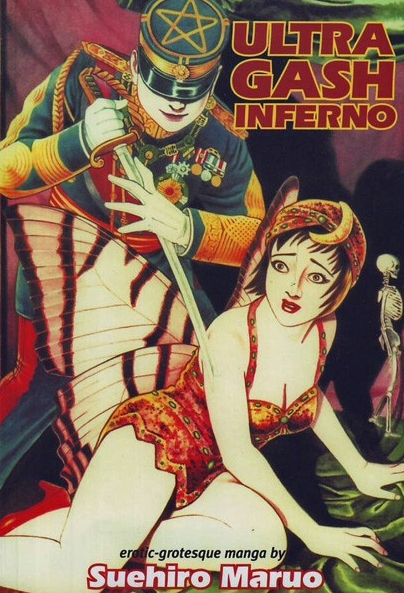

Ultra Gash Inferno is a collection of nine short comics from Japanese mangaka/illustrator Suehiro Maruo.

Ultra Gash Inferno is a collection of nine short comics from Japanese mangaka/illustrator Suehiro Maruo.

I highly recommend this book, but you shouldn’t buy it. It’s entertaining and well worth reading…just don’t spend money on it, yes? I do not offer this advice out of concern for your finances. Even if you are rich, you should acquire this book through through other means. Moving on…

There’s two things to review here, the work of Suehiro Maruo and the translation/editing of “James Havoc” and Creation Books. Maruo’s manga are brutal and nasty but very heartfelt and even strangely bathetic. They make you feel things. His characters are usually sweet, vulnerable-looking young people and his calendar seems permanently set in the nostalgic past.

His art is really interesting, there’s not too much I can compare him to except those 17th century Ukiyo-e woodblock prints. Maruo’s is a pure, unalloyed sort of manga, removed from all influences of Walt Disney and western iconography.

People call Maruo a mangaka/illustrator but I really think “illustrator” should come before the slash. Maruo draws manga but he’s more at home with stationary, tableaux-like images. He draws motion poorly, and whenever he tries a more stereotypical manga trick (like speed lines) the result appears artificial and disjointed.

“Putrid Night”, the earliest work on here (1981), is about sixteen year old Sayoko, who is married to a cruel and brutish samurai. He is hinted to have killed his first wife and soon we only feel glad at her fortunate escape, for marriage to this man is hell. Sayoko hatches a plan to kill her husband and escape with a young suitor, but of course, things never work out quite right, and sometimes all you can do is enjoy hell. “Shit Soup” is a gross-out comic, probably inspired by George Bataille, that features people having sex, drinking piss, eating shit, et cetera. Hard to believe that Maruo would just make a throwaway porn comic, I guess he wanted to make some kind of transgressive statement but needed to sex it up a bit before he could find a magazine that would print it. “Voyeur in the Attic” is about a man who witnesses infanticide, and rather than do anything socially responsible he becomes a participant in a dirty game. “Nonresistance City” is a 82 page comic set in post-war Tokyo, and is maybe the most mature and emotionally engaging thing on here.

I am a huge fan of Suehiro Maruo. Unfortunately, there’s a middleman here.

The book was edited by “James Havoc” (a pen name for another author), and he does nothing but fuck up the book. Sound effects aren’t edited into the art, they’re reproduced in awkward looking block text at the bottom of the panels. I wouldn’t mind too much if this was a scanlation, but come on, this is an actual product for sale. Some professionalism, please. The quality of the images looks faded out and weird, like bad quality scans.

Worst of all, he takes it upon himself to “improve” the book with extracts of his trademark “William S Burroughs on even more drugs” prose. “WE ARE BLACK SUNLIGHT, A VORTEX OF ANAL SWEAT IN THE SUCKLING SKY.” Oh, fuck off and leave the book alone. We’re here to read Maruo, not you. This sort of nonsense finds its way into nearly every single comic.

With the annoying editing, and the fact that Maruo likely has never seen a yen from this collection (tip: type “Creation Books” into Google), you’d be stupid to buy this. One hopes more (and better) English-language releases of Maruo’s work will be forthcoming. Treat this as a view into the world of one of Japan’s most provocative artists…however, you must look through a distorted lense.

This story sails under false colours.

This story sails under false colours.

During the golden age of piracy it was common for pirates to deceive merchant vessels by flying the flag of a friendly country, such as the Union Flag or the Cross of Burgundy. Only when escape was impossible would they run up the Jolly Roger. This book used a similar trick on me. It starts out as a funny story where a caddish young politician, drowning in bad publicity, flees the country on a boat bound for the far East. Soon (while he’s at sea, incidentally) The Torture Garden completely changes in tone and style.

Octave Mirbeau was a 19th century French journalist, novelist, and full-time burr in the establishment’s saddle. This is one of his most remembered works: a very excessive satire story that seems to be the bang-from-behind offspring of Jonathan Swift and the Marquis de Sade. The hero (nameless, as best I can recall) meets shipboard a depraved young woman called Clara, who has all sorts of issues to discuss with her inner child. She seems demur and immune to flattery, but comes to life at the slightest hint of cruelty, violence, or pain.

The book is very funny. The characters are picaresque and exaggerated like the ones in George MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman books. I laughed at several parts, such as this exchange, where a sailor is attempting to impress Clara.

“Well then?” she said maliciously, “so it’s not a joke? You’ve eaten human flesh?”

“Certainly I have!” he answered proudly with a tone that established his indisputable superiority over the rest of us.

Clara and her male companion journey to China’s famous “Torture Garden”, a place where criminals go to die. The Asians are sophisticated and evolved in this matter. Where Europe allows its prisoners to languish in dark dungeons, China’s prisoners live and die in massive gardens well equipped for all forms of torture. Viburnums enriched by bilirubin. Azaleas watered by arterial gore.

Mirbeau writes satire really well. One of the funniest parts has a seasoned Chinese torture ranting about Westerners invading the land and bringing their crude and barbaric methods of torture with them, with no respect for Chinese tradition.

Our protagonist’s goes on a tour through this garden, learning about plants and pain. The garden is really quite extraordinary. There is a method of torture involving a rat and a basket and a heated brand that they could never have thought of at Gitmo Bay.

Our protagonist is appalled by everything he sees. Clara laughs and mocks him. These exchanges turn the old trope John Wayne telling the woman to close her eyes as she walks past the dead Injuns on its ear…although it’s hard to feel sorry for our hero. He has the option to turn back at any point, yet he continues exploring the garden. Then, in the book’s final passages, even Clara’s walls and rationalisations break down, and the result is one of the most frank and disturbing scenes of emotional implosion I’ve encountered in a book.

Although it always keeps satire close to its heart, I must emphasise that there are very few books as gruesome as The Torture Garden. The 120 Days of Sodom and Story of the Eye make their nature clear at the outset. The Torture Garden tricks you. I wonder how many idle French intellectuals sat down for a comfortable tale of misbehaving rakes and armchair rebellion, and were exposed to…this.

They say nobody should write books about war. The ones who weren’t there will never understand, and the ones who were there remember everything with the most brilliant hindsight a man can have.

They say nobody should write books about war. The ones who weren’t there will never understand, and the ones who were there remember everything with the most brilliant hindsight a man can have.