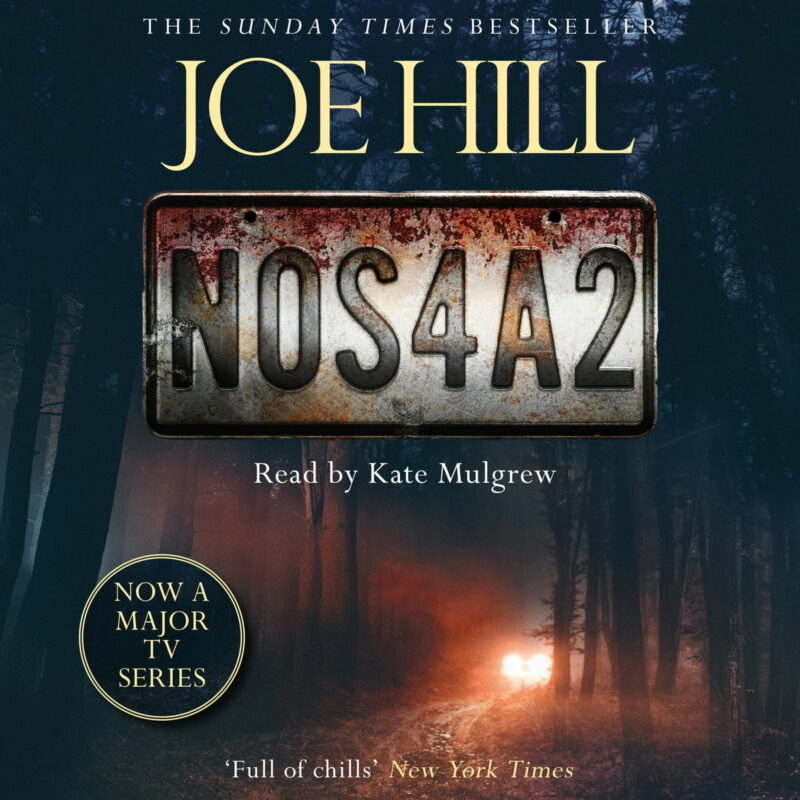

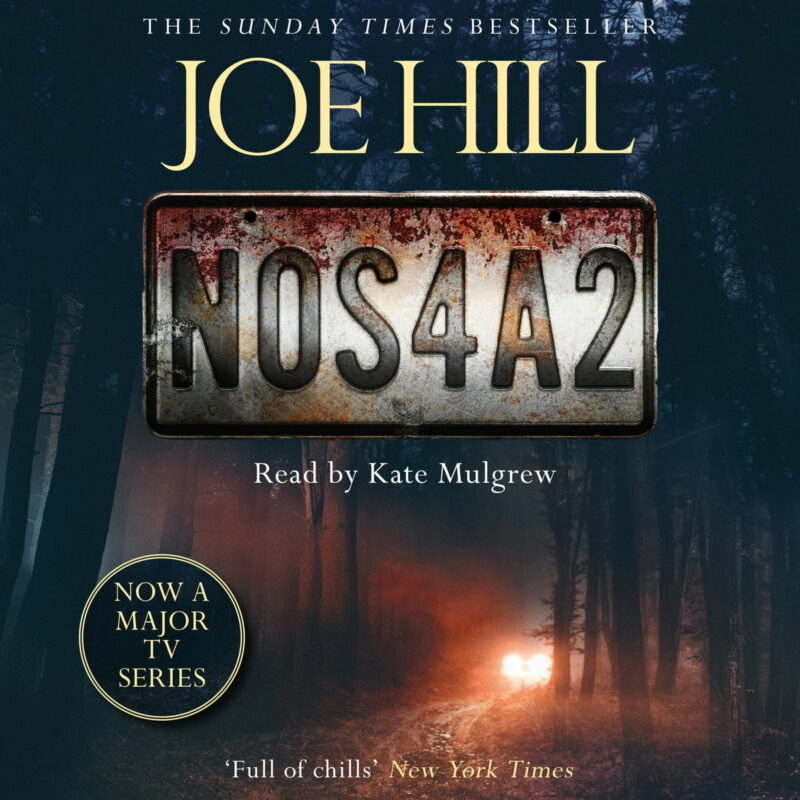

The title shows Joe Hill’s best side: his playful wit. The book is funny at times: and often because it means to be. It also shows his fatal flaw, which we’ll get to soon.

The book’s about larger-than-death pop-villain Charles Talent Manx III. He’s a vampiric creature who kidnaps children in a Rolls Royce Wraith with a NOS4A2 vanity plate. He’s Dracula, John Wayne Gacy, and Michael Jackson at once. Why couldn’t I have been murdered and left on the side of the road by this guy in 1973, instead of that Dennis Rader jerk?

Set against him is Vic McQueen, who also has paranormal gifts: She cross an imaginary bridge and find missing things at the other side. This is described as an “inscape”, a mental shortcut that some creative types exploit (damaging their health in the process). Maybe not the most original or subtle metaphor for drugs, but that’s where NOS4A2 works. The story is bold, brash, and full of color – even if it’s usually color from a spraygun and not a paintbrush.

But the pun in the title doesn’t quite work – nitrous oxide systems first appeared in automobiles in the 1950s, and Manx’s car is from 1938 – and this points to the problem with NOS4A2: it never gains the weight and heft of reality. It’s obviously a construct. The book is too clever, too full of references. It badly wants entry to the gated world of classic horror novels, to the point where it tries to pick the lock.

The plot reads like Stephen King’s ten most famous novels compacted in a hydraulic press. Vampires. Haunted car. Haunted house. Girl with supernatural gift. Ancient evil that feeds of children. Drug metaphor. Creepy undead kids. I was about to say “at least there’s no cornfield”. Then I remembered that there is a cornfield.

Sometimes the namedropping is blatant, such as when we find that Manx’s wintery retreat is in Colorado, or when Bing says “My life for you!” to Manx.

If I’m just lazily listing things, that’s how the book feels, too. While it would be unfair to call it a grinding, soulless list of in-jokes and references like Clown in a Cornfield (the world’s first “young adult” book written exclusively for forty year olds consoomers) the book is deadened by its use of horror cliches. Events in NOS4A2 don’t happen to people, in places. They happen to stock figures in generic settings, most of which are lifted from 1980s books from the author’s own father.

Is this what horror’s supposed to be? I don’t think so.

Horror is meant to be a scalpel to the amygdala. It wakes instinctive fears you might not have been aware you had. It thrives off the unexpected, off dissonance. It can’t become ever become “cosy” or a franchise without losing its soul, but we’re at the point where there’s 20 designated “spoopy ideas” that books variously shuffle around and recombine in various orders, hoping to strike gold again. It’s a real shame. Horror needs to climb out of its own ass.

Another problem is that NOS4A2 is paced very fast. The narrative’s sediment is never allowed to settle. Hill is trying to do too much here – right out of the gate we’re bombarded with various unrelated bizarre, dramatic, or supernatural things (Manx, Vic McQueen’s magic bike, Bing), along with rapid shifts in time and place that leave book’s cohesion in tatters. And there’s no displacement when paranormal events start occurring, because they occur almost from the first page!

Stephen King’s books are usually paced far slower, which gives them a certain stateliness. The nightmarish gross-out scenes are freighted down by a lot of everyday life – nothing happens for an extremely long time in Pet Semetary or The Green Mile, because he’s building up the characters and their world. NOS4A2 thinks it can race through all that in fifth gear, but it really can’t.

In the final pages, the action builds up to an exhilerating climax that goes for broke, takes out a small loan of a million dollars, then spends that, too. Hill’s a gifted natural writer, with an eye for quick, effective characterization. Early on we meet Bing Partridge, a chemical plant worker who might be developmentally disabled. Bing exclusively reads old pre-war magazines and paperbacks, and when he writes a letter, his prose is hilariously stilted and old-timey. This is a subtle but good touch. So is the way Vic goes from idolizing David Hasselhoff to hating him. Lots of writers forget the huge gap between twelve year olds and fourteen year olds, but Hill hasn’t.

But sometimes his characters ring hollow. “McQueen” is an irritating, phoney-sounding name, meant to anchor the book in car culture, and she’s such a congenital screwup that we don’t believe she’d grow up to write a best-selling puzzle book full of brain-teasers. And Vic gets a romantic interest: a big, mellow easygoing from the left side of the bell curve. Yet he’s characterized with a fannish interest in Marvel comics (to the point where he’ll argue what color the Hulk’s skin should be). Have you ever met a comic book fan? They’re not mellow and easygoing. They’re angry, vicious, and highly strung. Lou Carmody caring about comic books is about as believable as Barney Gumble running The Android’s Dungeon.

Most of the book is entertaining and well written. I just don’t enjoy (or respect) a lot of what it’s trying to do. NOS4A2 is loudness-war Stephen King, with the bad amped up far more than the good.

Alan Moore was surprised to learn that people idolise the character of Rorschach. That’s weird: how could comic book readers possibly relate to a smelly, antisocial creep who can’t get a girlfriend?

In general, superhero stories are fantasies of power, postcards from WishIWasistan**. Superman is the shards missing from your body and mind: he’s strong where you are weak, and certain where you are doubtful. Your hands shake, his smash through walls. The blandness of classic superheroes is a feature – you’re supposed to imagine your face on top of theirs. Don’t rage at the dying of the light; let Kirby and Ditko draw a new, better sun.

Or so goes the theory.

Power fantasies have a problem: life is defined by challenges and limitations, so what would life mean if there weren’t any? Where’s the fun in being God, in staring at a “YOU WIN!” screen for eternity? In 1859 Jean François Gravelet-Blondin successfully crossed the Niagara Falls on a tightrope, but that wasn’t exciting. The exciting part was that he could have fallen: that success wasn’t inevitable. Trying to win is exciting, but winners are dull.

So is reading about winners. Many golden age superhero comics have the tenor of a scrappy rags-to-riches saga about Goldman Sachs. Superman is so laughably overpowered that there’s no possible tension when he beats up a couple of thugs: he can’t lose, and you’re just watching the inevitable happen. Series after series slam to their deaths against the wall of this problem: superheroes are defined by being excessively powerful…but excessive power creates boredom. There’s nothing interesting about being very strong.

Many comic books, having destroyed the drama, think they can restore it by making the villain extremely strong, too. Aside from defeating the purpose of a power fantasy (why not just tell a story with two regular humans?) it starts a hyperinflation death-spiral (the hero has to defeat the villain at the end, so issue #2 needs an even stronger villain, etc). The all-powerful god becomes a hamster running on a wheel. The end result is something like Dragon Ball, where every new season “ups the stakes” by throwing another few zeroes onto Goku’s power level until finally you turn twelve and stop giving a shit about Dragon Ball.

But there’s a more interesting type of comic figure: subheroes. Swamp Thing, Rorschach, and Third Example. They are portraits of human weakness and frailty. Although they might possess super strength or speed (you gotta have action scenes, I guess) the soul of the character is in their weakness and alienation. They inspire pity, not envy.

Being different isn’t fun: that’s the truth superhero stories have to grapple with. Even if you’re better than other people, this usually just isolates you. Have you seen a pro basketball player, or an Olympic-level swimmer? They’re genetic mutants; swirling stormclouds of genes have settled upon their skeletons in such a way that they can play SportsBall at a high level. They haven’t done anything to deserve this. They’re products of chance. And have you seen how awkward they look when they try to wear normal clothes? Or do normal activities? They’re like broken humans. And suppose there’s no SportsBall to play? What would they do then?

Sam Kieth’s The Maxx (#1-35, serialized in 1993-1998 by Image Comics) lives and dies inside this teleological dead zone. “Being super-powered is bad.”

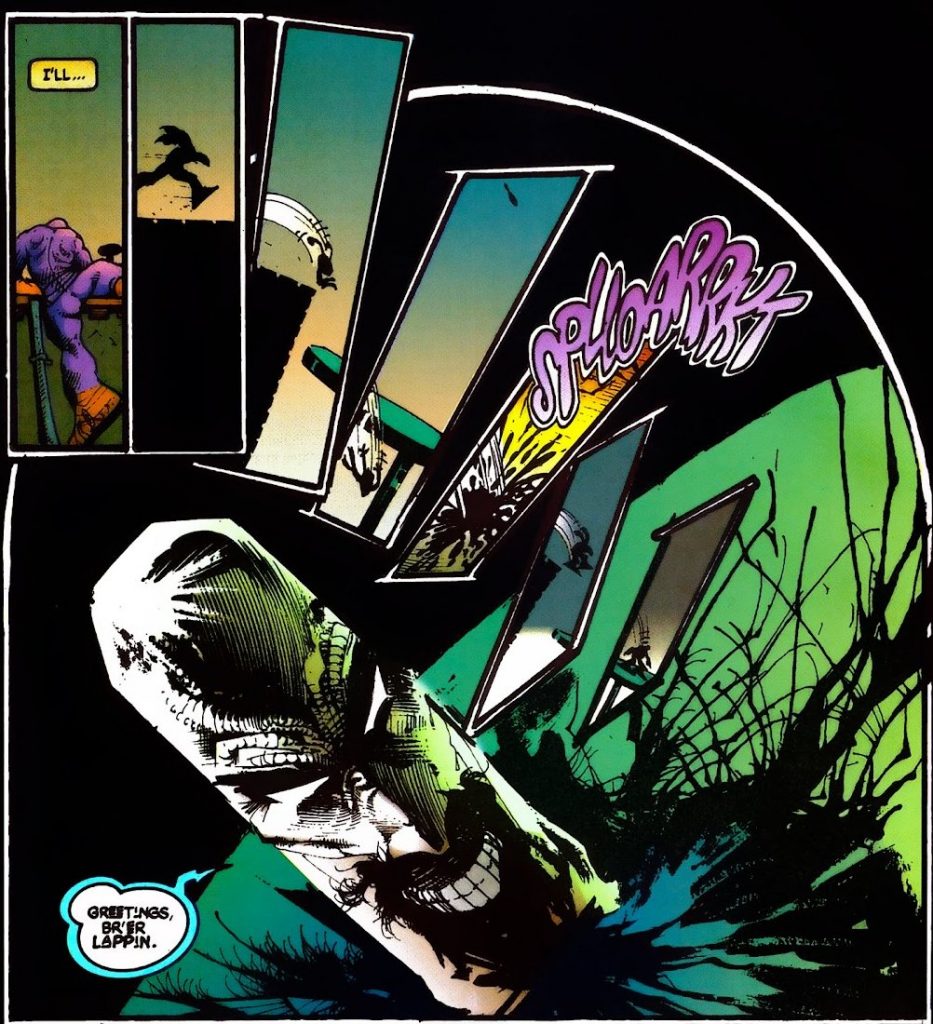

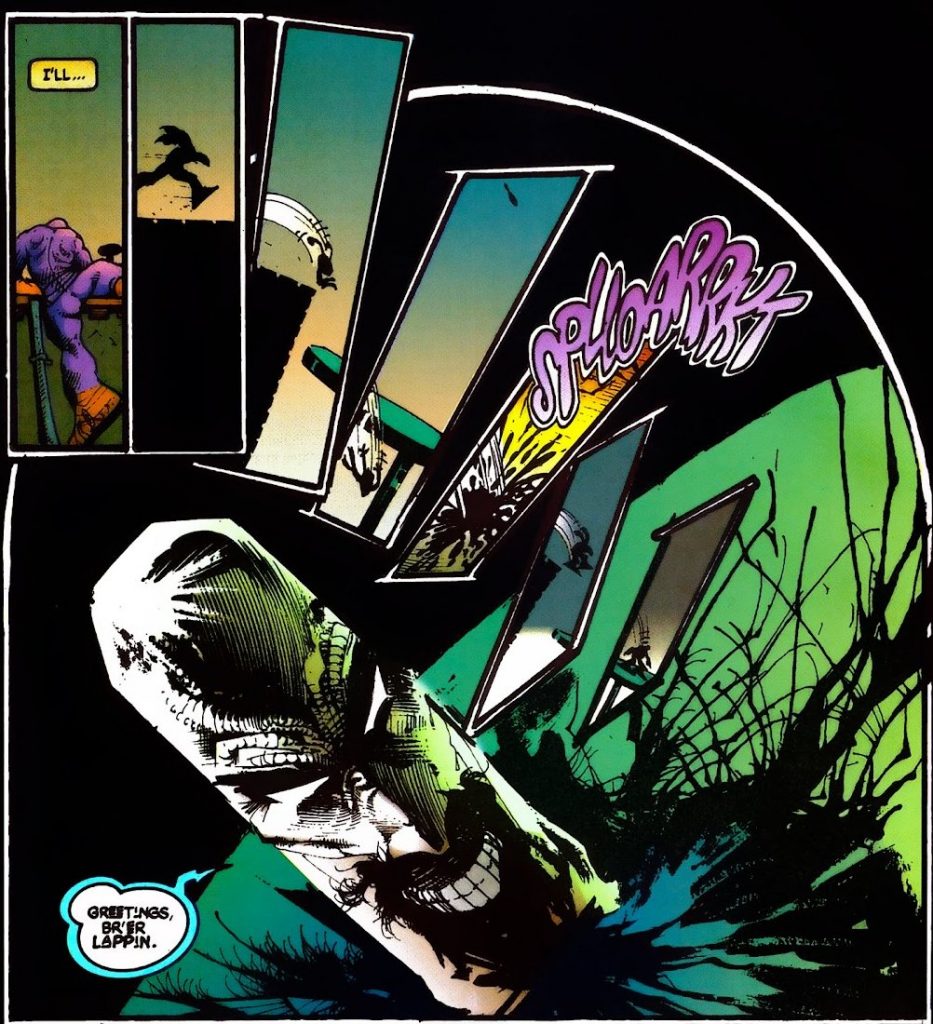

At it’s core, it’s an unusually good depiction of a subhero. Average out every panel of the titular character and you’d have the titular character lying in a dumpster, legs tucked pathetically like a broken doll. He lives on the street in a dark urban hellhole. Every street apexes into a black scream. Leprosy spots of mold scar the buildings, and everything around him seems at the point of structural collapse.

The Maxx tries to do standard superhero shit like saving people from thugs, but instead he gets arrested, harassed by cops, and misunderstood by civilians. It’s too much to deal with. When he slips into unconsciousness and enters a delusive dreamland, it’s clearly with some relief.

“I don’t have a TV now, but that’s okay. The shows in my mind are always better.”

He’s big and tough, but his muscles are like a high-performance NOS engine in a city gridlocked by traffic. The city is so big, evil, and hostile that there’s nothing he can do except slowly die inside its depths. He’s a lymphocyte, dutifully maintaining the health of a few cells a vast, swelling cancer. Why does he exist? For the same reason Yiao Ming is 7’6″: by accident. He has to create his own meaning…and he can’t.

When he shuts his eyes, he enters a happy place where things make sense. He has a purpose now: he’s a brave warrior in an ancient landscape that he calls it the “Outback” (but it’s clearly not Australia, it’s full of erupting volcanoes), along with various odd creatures such as white rabbit-like entities called Iszes (rabbits are a recurrent motif throughout the comic). In the real world he has just one friend: a “freelance social worker” called Julie Winters. She bails him out of jail, and generally acts as a protective mother figure. But in the Outback, the relationship flips: she’s a queen he protects from harm.

That’s the soul of The Maxx: a troubled Untermensch caught in maladaptive daydreams. The comic’s most brutally effective when it switches from Maxx’s fantasy reality to the real one, intercutting from glorious sunlit landscapes to the reality he’s dwelling inside: a labyrinth of poverty, rapes, robberies, and murders. From lord of the plains to lord of a couple of rainsoaked cardboard boxes in a gutter.

Julie (arguably the comic’s real main character) is also hiding from reality. She is empathetic and compassionate, but also given to bizarre rants about how crime victims deserve what happens to them. She exists parallel to the Maxx in his dreams…but that creates a quandary. Dreams, by definition, happen inside one person’s head. There is no such thing as a dual-person dream. So is Julie a figment of his fantasies, or is he a figment of hers?

This could be read as commentary on mainstream superheroes, and the toxic fantasies they inspire. Reading superhero stories doesn’t make your own muscles any bigger: in the end it’s a form of hiding. Escapism is not a thing. You can’t “escape” a life of misery by entering a fictional world, you can only be paroled for a short period. In the end you have to close the book, and go back into your prison cell.

The Maxx could also be read as artist Sam Kieth working out his personal frustrations with the business. For decades, he’s eked out a career on the edges of the comics trade. He’s talented, but never really found a home.

In a field that rewards bragadoccio and egotism, Kieth is humble to the point of self-loathing, savagely ripping apart his own work. I wish Rob Liefeld had Sam Kieth’s self-confidence, and vice versa. He’s also an artist with a unique style and vision in a sausage-machine of an industry that just wants you to crank out filler arcs in between the occasional marquee “event” (ie, The Death of Superman). His work attracted hate mail as well as praise. He doesn’t draw superheroes correctly. His style is too idiosyncratic. His feet are weird. He famously blew up a steady gig on Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman (and The Maxx contains a jab at “necro-nerds and sand-freaks”), and from then on was assigned largely to janitorial work (such as drawing covers). He doesn’t fit in any more than the Maxx does.

“Kids would write in and say things like: ‘Wolverine’s okay, but his back is too round.’ ‘What’s up with Wolverine’s feet? Why are they growing?’ And, “Wolverine is really out of proportion, I think your artist is losing his mind or something.” And it was funny, because the letters I would get would be kids who really loved it, or kids who were saying ‘Why are you ruining my universe?’ They had a very specific view of the world. “I’m going through latency,” they wouldn’t say it in those words, but, ‘I’m going through this world view phase where I’m trying to categorize and order things, and you’re causing chaos by giving me a version of things that are drastically different from everything else. So please, please, please go away and not do that anymore.’ So, in that way it was almost a relief when I went off and did my own book, because then I could screw around and introduce my proportions.” – Sam Kieth, Sequential Tart

Ironically (or appropriately) The Maxx is the thing he’s most remembered for. Serialized in 1993-1998 by Image, it’s an odd beast: a superhero comic that barely reads as such. Kieth has no interest whatsoever in zany fights, costumes, lore, and continuity. Instead The Maxx contains a painful, cathartic character study. A lot of pagetime is spent developing the relationship between Julie and a girl called Sara (who has pronounced school shooter tendencies, five years before Columbine), with Maxx taking a backseat in later issues. Daniel Clowes’s Ghost World is a much more apt comparison than Rob Liefeld, and the obligatory “crossover” strips where The Maxx gurns and poses next to Flatulence Man and Nipple Boy (I’m not up to speed with Image’s roster) felt even more forced than they usually do.

Kieth may not have known it, but he was poised to ride a wave. MTV is most famous for brilliant reality TV such as The Ashlee Simpson Show and Engaged and Underage, but once they grudgingly put original animation on the air, too, and the “adult animation” explosion of the mid nineties meant some stuff made it to TV that normally wouldn’t.

In 1995, The Maxx was adapted into an animated series. From what I’ve heard, MTV Producer Abby Terkuhle secured the TV rights after he attended an art showing by Kieth in New York and liked the cut of his jib. Directed by Gregg Vanzo, The Maxx ran from April to June on MTV’s Oddities block (which was a kind of successor to Japhet Asher’s Liquid Television). It was a test tube for extreme styles and odd personalities, some of whom would later find mainstream success (by “some” I mean Mike Judge, but bear with me).

Each episode ran for about thirteen minutes, which covered about one issue each. It tells an abbreviated version of the comic’s story (mostly issues #1-11). The Maxx’s backstory is hinted at, but not literally explained. Sara’s role is reduced, and she feels a little superfluous. This means snipped away, and curtailed. Huge folds of plot are scissored away, the remainder folded double and stapled back into place like skin over an amputation.

Aside from this, it’s incredibly faithful to the comic. It’s one of the few cases where MTV adapted someone else’s property and didn’t change a thing. Maybe they couldn’t figure out what to do with it, so they let Vanzo and Kieth have free rein.

The budget wasn’t high, but there’s some good, fluid animation in places (the production team that created MTV’s The Maxx would later work on Daria). Then there’s a few “limited animation” scenes, where only the mouths move – these are infrequent enough that they seem like a stylistic choice, rather than “fuck, we ran out of money”.

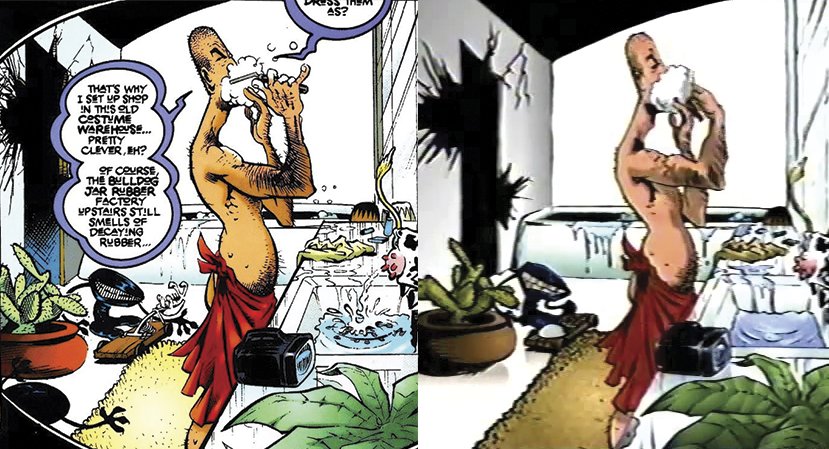

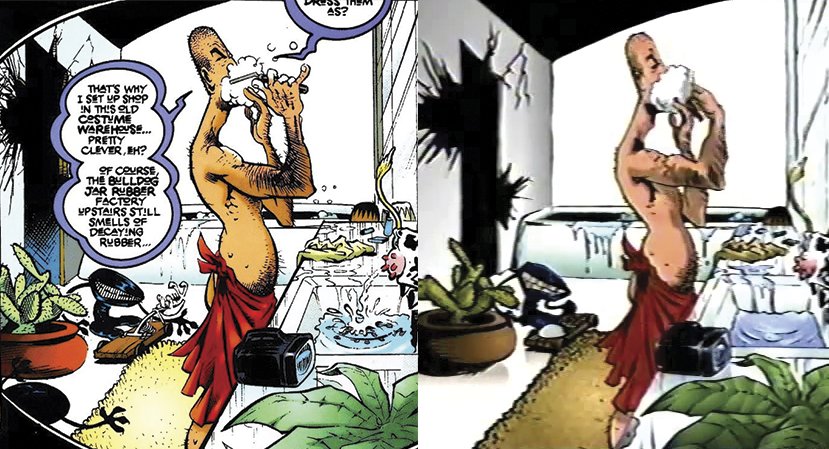

For establishing shots, the show uses live-action, and even some CGI (which looks about as good in 2022 as your dad’s asshair getting waxed, but surely impressed in 1995). Otherwise, it closely follows Kieth’s original art. Sometimes it is Kieth’s original art. You can find instances where they literally scanned in pages of the comic.

Might the show not be too faithful to its source material? At times it’s like a comic book shoved into a VCR player with a crowbar. Comic storytelling (soundless, consisting of broken images with no temporal element) is a little different to filmic storytelling (which can smoothly flow from moment to moment), and often the show adapts something that it shouldn’t adapt.

For example, The Maxx’s internal monologues are pretty distracting (and often needless : explaining things we can see happening on the screen). Supervising producer John Andrews explained that they had a short schedule to create the show, so they didn’t really have time to “revisualize” The Maxx. It was faster to just adapt the comic verbatim.

The writing in general is a bit odd. The Maxx’s origins are never addressed in the show, but in the comic he’s a plumber who was murdered. Either way, his dialog sounds too elaborate, too formal and poetic.

For the truth will destroy her…at least that’s what the villain told me. But who can believe a villain? Still, as I talked to Julie, I can’t help remembering his words. He never told me anything straight out, only in riddles. But he implied a lot. He hinted that maybe she was in danger, maybe from herself.

It’s a subtle thing to have to express, but a lot of the writing is just clunky. It sounds incorrect. Comic writing has a different cadence to film writing (which has to actually sound like believable speech), and they needed a different tone for the show.

Other problems occur because of plot details that were cut away. The story can be difficult to follow. Max’s origins are pared back to nothing. Sara is heavily overdeveloped, given how little she has to do.

But the real issue is found in the villain, Mr Gone.

Right out the gate, Mr Gone is established as a psychopathic rapist-murderer who uses magical powers to avoid detection. He lives inside the Maxx/Julie dreamworld, but he has figured out how to cross over and has brought some Iszes with him (the creatures, usually benign and white, turn black and evil when they enter the human world – which feels like Kieth’s judgment of comic book morality applied to reality). He’s genuinely scary.

Everything that happens to Mr Gone after this undermines this portrayal. He’s used for comic relief. He’s easily outwitted by Julie. He goes on childish misogynistic rants that sound like they’re from an incel message board – you almost expect to hear him whining about Chads and Staceys. We have no idea of what he actually wants to do, or is trying to accomplish.

In later episodes, he’s devolved into a wacky, nearly-harmless court jester (“that’s Mister Gone to you, claw boy!”). The true antagonist of The Maxx isn’t Mr Gone, it’s Maxx and Julie’s own natures: and the skeletons in their own pasts that they’re not brave enough to confront. This is good. I’d rather have that than another “villain of the week” strip. But it leaves Mr Gone in an odd place: a villain without a denouement, an open sentence without a closing punctuation mark.

In the comic, we see more of Mr Gone and he’s depicted more believably. The show version is brutally truncated, and his character never settles into something that makes sense.

The era of adult animation didn’t last. Ralph Bakshi’s Spicy City was cancelled. Eric Fogel’s The Head and Peter Chung’s Aeon Flux cycled through a few iterations of themselves and then disappeared. Todd McFarlane’s Spawn lasted a whopping eighteen episodes before being shitcanned: a monumental run by the standards of the genre.

“Adult animation” regrouped around the South Park ideal: satire and toilet humor. I like many of those shows, but it was a sad end. Animation can show us distant worlds and things beyond comprehension. Instead, it was limited to making fart jokes at Middle America.

Like the character, The Maxx is an interesting mixture of strengths and weaknesses. A mountain of excessive exposition…in which gems of psychological insight sometimes glow.

Confusing characters…but when they settle into focus, they are as sharp and believable as any I’ve seen.

Weird writing…that conjures a city on the edge of a hallucination, the world as seen from the bottom of an empty whiskey bottle.

That’s The Maxx. There’s little else like it, except a mirror.

(**Derailment zone: in Hegel’s The Phenomenology of Spirit he says that “identity is the identity of identity and non-identity.” What does he mean by this? Did he just enjoy saying “identity” over and over? The peak of Mount Hegel is as foggy as ever.

What I think he means – not sure – is that a wholistic identity also includes an accounting of the things you are not.

Think of how a broken plate implies the shape of an unbroken one (otherwise, you wouldn’t know it’s broken). Or how a ragged coastline suggests the shape of the sea (and the sea the coastline). Or how mIspelLd wRdS guide the mind back toward their correct form.

A full description of your identity entails not just positive space, but negative. If you dream of being huge and muscular, then hugeness and muscularity is (in a sense) part of you. It wouldn’t matter how puny your real-life body is. Superheroes, in Hegel’s view, are fictions of the unbroken plate: who you’d be if you weren’t shackled to two-hundred-and-counting pounds of greying meat, pinned like a sagging, hairy butterfly to a universe that despises you. They are IOUs from God. The form, perhaps, you’ll have in Heaven…

…or so goes my questionable interpretation.)

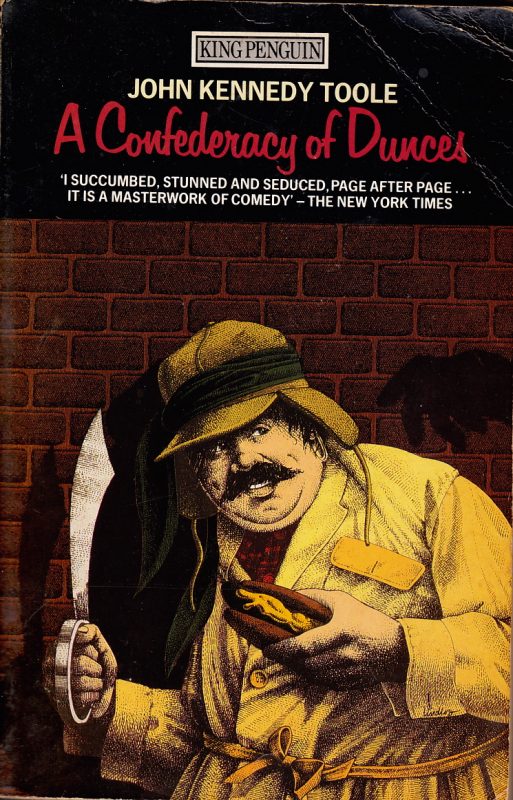

“What I want is a good, strong monarchy with a tasteful and decent king who has some knowledge of theology and geometry and to cultivate a Rich Inner Life.”

Incredible book. Maybe the funniest ever written. I dearly wish I could go back in time and experience it again for the first time.

How did Toole, a 26 year old who lived in a few places and met a few people, write a satire so sharp and cutting? And universal? You will encounter nearly every person you have ever met in A Confederacy of Dunces, and witness nearly every social absurdity. The book is a high-wattage laser focusing on excesses of human behavior until they either glow or shatter. It’s like an American version of Waugh’s comic novels: not as well-written, but funnier, moving with a lighter step, and with even more vivid characters.

The most vivid is Ignatius J Reilly, an obese, arrogant history grad who lives with his mother in 1960s New Orleans. “History grad” doesn’t cover Ignacius. Astronomers don’t want to live on Jupiter, and geologists don’t want to live in a cave, but Ignatius wants to live in the Middle Ages.

He feels a sullen, burning anger against all of modernity. He is proudly jobless (“Apparently I lack some particular perversion which today’s employer is seeking.”) and occupies himself by writing “a lengthy indictment against our century. When my brain begins to reel from my literary labors, I make an occasional cheese dip.” He is laughable, gaseous, and contemptible, the spiritual ancestor of the neoreactionaries. He offends nearly everyone he meets, although not half as much as they offend him. He feels a kinship with the “Negroes”, however, his brothers in societal oppression.

But Toole makes Ignatius sympathetic, despite his tirades and hubris. We’ve all met this guy, or been him. He’s the kid who never got invited to any parties and has decided that it’s just as well: he’s too civilized for those nasty brutes. The sadness at the heart of Ignatius’s self-delusions cause something even stranger to happen, we start to like him.

Francois Truffaut famously said that it’s impossible to make an anti-war film because the nature of film makes exciting. Literary fiction (where we can see inside a character’s head and can witness their internal logic) does the same for egomania. From the outside, Ignatius is intolerable. From the inside, his gale-force personality wins us over. He does indeed have, as he puts it, a “Rich Inner Life”.

After a car accident puts the family in debt, Ignatius is faced with the horrific fate of having to work at a job. The bulk of the novel involves him trying to do so, and failing. The actual story’s pretty thin and episodic: this reputedly scotched its chances of publication within Toole’s lifetime – it was rejected by Simon & Schuster’s Robert Gottlieb because, apparently, he saw no point to it.

But there is a point: the ways arrogance is a mask for insecurity. Everything Ignatius says and does is a rationalization for his own failures. He watches far more movies than most people do, but justifies himself by saying he’s injuring himself against “perversion and blasphemy”. When he struggles to fit into a uniform, he laments that it’s made for a modern person’s “tubercular and underdeveloped frame”. In his off-hours, he writes invective-filled letters to a young female beatnik socialist named Myrna Minkoff who he is obviously obsessed with.

Myrna Minkoff is another character who comes alive on the page, which is saying something, because we never meet her until the end. She writes long letters back to Ignatius, focusing on his physical inadequacies, sexual repression, and urgent need for therapy. Supposedly, she is based on the hyper-aggressive female activists Toole encountered while teaching in New York. “Every time the elevator door opens at Hunter [University], you are confronted by 20 pairs of burning eyes, 20 sets of bangs and everyone waiting for someone to push a Negro.”

She is the opposite of Ignatius politically, but his equal at deluding herself. She’s putting on a play about interracial marriage, and has forged links with the female black co-star. “She is such a real, vital person that I have made her my very closest friend. I discuss her racial problems with her constantly, drawing her out even when she doesn’t feel like discussing them — and I can tell how fervently she appreciates these dialogues with me.”

There are other characters: a couple of ess-doubleyous at a French Quarter strip club, some gormless souls at a family-owned jeans factory, a bumbling police officer, etc. They are interesting on their own but become dim shadows when set against Ignatius and Myrna.

The book is famous for its detailed depiction of New Orleans. I always dislike it when reviewers say something like “the city’s almost like another character!” Cities are cities and characters are characters. An urban environment doesn’t have to be a person to be interesting, that’s just anthropomorphism. But New Orleans – the patois, the heat, the culture-clash – is an inseparable part of why Confederacy works. Whenever the action threatens to get a bit too ridiculous there’s always that anchor to pull it back to reality – this sense that it’s in a real place that actually existed. Little details, such as the daily life of a hot dog vendor, are rendered in believable accuracy.

The best part? The dialog. Confederacy is possibly the most quotable book ever written. I can recite large sections of it from memory.

“I mingle with my peers or no one, and since I have no peers, I mingle with no one.”

“In my private apocalypse he will be impaled upon his own nightstick.”

“Do I believe the total perversion that I am witnessing?”

“If you molest us again, sir, you may feel the sting of the lash across your pitiful shoulders.”

“This liberal doxy must be impaled on the member of a particularly large stallion!”

“Go dangle your withered parts over the toilet!”

And so on. The book’s a ridiculous caricature, but like a caricature, we recognize everything it. Forty years after it was published, the book still seems eerily accurate to how people think and behave. Maybe life is more limited than it seems: its complexity spun out of a few repetitive people and scenarios, just as a jewel’s intricacies can be understood from seeing a single facet. Either way, when Confederacy of Dunces reaches its disastrous end, you’ll want Ignatius to prevail in his one-man war against the modern world.