There are books that don’t sound real.

“A parable from the 70s about a seagull who wants to fly fast. He strives day and night to set new speed records. The others gulls make fun of him, but he never abandons his dream. Finally he dies and goes to heaven, where he attains perfect speed.”

The book sounds like a parody of banal inspirational literature. “The author must be a Holocaust survivor” was my thought while reading it. “Or a child abuse survivor. Or a something survivor. That’s the only way this got published: on the back of a very sobby sob story.” I was wrong, Richard Bach was an aviator turned technical writer, and Jonathan Livingston Seagull took wing entirely on its own merits.

There’s a thing called “irony poisoning”, where detachment is used as a weapon against criticism. “Didn’t laugh at my joke? Well guess what, dumbass, I never meant it to be funny.” Jonathan Livingston Seagull has the reverse problem: sincerity poisoning. It’s painfully earnest, solemn as a hymn, and blind to its own ridiculousness.

Why is the seagull called “Jonathan Livingston Seagull”? Why is his surname his species? Can seagulls smile (as they do here, repeatedly)? How does he always know his exact velocity and altitude? It doesn’t even make sense to ask questions like that: the book exists in its own world.

Sometimes this works. Bach’s story choices create a weird and dislocative mood, and you go along with Jonathan Livingston’s odd adventure. At times it approaches CS Lewis’s vision of a fairytale for grown-ups.

At other times I agree with Roger Ebert’s pan: “a book so banal that it had to be sold to adults; kids would have seen through it.”.

One problem is that seagulls can’t actually do much. Jonathan just flies, and flies, and flies, setting pointless speed records over the ocean that nobody will remember, think, or care about. This is a metaphor for following your dreams and believing in yourself (along with some Christian/Buddhist spiritualistic hippie mumblecore), but the meaninglessness of it all makes his quest tragicomic, not inspirational.

The book has three sections (dealing with Jonathan’s life, adventures in Heaven, and return to Earth). In 2013 it was reissued with a fourth part, which is set hundreds of years after Jonathan Livingston’s life. The flock that rejected Jonathan now reveres him as a spiritual figure, but has buried his teachings in stultified ritual and cant. This is satire about organized religion, and seems to have been created reactively to silence critics who found the book pointless (not so – apparently it was written concurrently with the first three). It’s more interesting, but also less sincere.

The book is slim and could have been slimmer. Photos of seagulls pad the pages. Specifics about angles of descent and wing profiles about are endlessly elaborated, to soporific effect. It’s like reading a book by an autistic child whose special interest is the airspeed of birds.

From a thousand feet, flapping his wings as hard as he could, he pushed over into a blazing steep dive toward the waves, and learned why seagulls don’t make blazing steep power-dives. In just six seconds he was moving seventy miles per hour, the speed at which one’s wing goes unstable on the upstroke. Time after time it happened. Careful as he was, working at the very peak of his ability, he lost control at high speed. Climb to a thousand feet. Full power straight ahead first, then push over, flapping, to a vertical dive. Then, every time, his left wing stalled on an upstroke, he’d roll violently left, stall his right wing recovering, and flick like fire into a wild tumbling spin to the right. He couldn’t be careful enough on that upstroke. Ten times he tried, and all ten times, as he passed through seventy miles per hour, he burst into a churning mass of feathers, out of control, crashing down into the water. The key, he thought at last, dripping wet, must be to hold the wings still at high speeds — to flap up to fifty and then hold the wings still. From two thousand feet he tried again, rolling into his dive, beak straight down, wings full out and stable from the moment he passed fifty miles per hour. It took tremendous strength, but it worked. In ten seconds he had blurred through ninety miles per hour. Jonathan had set a world speed record for seagulls!

Being the world’s fastest seagull is only slightly more interesting than being the world’s fastest tapeworm, but this is the personality type the book appeals to: the pointless striver. The person who thinks that effort, in and of itself, is valorous. Jonathan Livingston Seagull is the battle hymn of the writer who can’t spell, the tone-deaf singer, the 5’2 wannabe pro basketball player, the aging LA actress who mails decade-old headshots to every agent in Hollywood. “Follow your dreams,” it says “no matter how unlikely – or pointless – success might seem.”

In the real world there’s a dark side to dream-following. Athletes cripple their bodies, entrepeneurs bankrupt themselves (and their partners and families), and naifs are exploited by scammers. Sometimes it’s necessary for a dream to end and the book doesn’t ever confront that possibility. Jonathan Livingston only wins. He wins so much he gets tired of winning. He barrel-rolls past every obstacle, breaking even the laws of physics, proving every doubter wrong. It’s pure wish fulfilment pornography, endearing and toxic. It takes twenty minutes to read and will ruin your entire life if you let it.

The more a monster is written about, the more it becomes the hero. Jason Vorhees was a villain in the first Friday the 13th. By the sixth or seventh, he’d become an icon, an institution, a machete and hockey mask on a t-shirt, with millions of fans cheering when he kills a camper.

Any book on forbidden behavior has to walk the same line. Psychopathia Sexualis: eine Klinisch-Forensische, Krafft-Ebing’s 1886 text on sexual pathology, is written with caution and asperity, clearly afraid that it will inspire as well as inform. It’s a catalog of deviant sexual behaviors, but doesn’t want to be a sales catalog. It hides delicate ideas behind a haze of Latin, and the reader will encounter terms like “paedicatio puellarum” (anal intercourse with girls), and “spuerent et faeceset urinas in ora explerent” (spitting, defecating, and urinating in the mouth).

The book is explicitly “addressed to earnest investigators in the domain of natural science and jurisprudence”. And “In order that unqualified persons should not become readers, the author saw himself compelled to choose a title understood only by the learned.”

These days, the telescope points the other way. Krafft-Ebing’s forbidden fantasies are all over the internet, and many aren’t even forbidden anymore. Now, it’s an interesting look at the 19th century man’s view.

Psychopathia Sexualis sees science shifting from the pre-modern view (where deviancy is caused by sin and moral failure), to the modernist view (deviancy is a pathology under the scope of medicine). There’s even parts where Krafft-Ebing seems to ancitipate the post-modern perspective of Thomas Szasz, where perversions don’t exist: just morally neutral preferences. This is seen in his discussions of “urnings”, or male homosexuals.

The observation of Westphal, that the consciousness of one congenitally defective in sexual desires toward the opposite sex is painfully affected by the impulse toward the same sex, is true in only a number of cases. Indeed, in many instances, the consciousness of the abnormality of the condition is want- ing. The majorityof urnings are happy in their perverse sexual feeling and impulse, and unhappy only in so far as social and legal barriers stand in the way of the satisfaction of their instinct toward their own sex.

There’s still premodernity to Krafft-Ebing’s thinking. Note the “jurisprudence” part of the intro – the book (in part) is meant to assist law enforcement in rendering swift and effective punishment to wrongdoers. He frequently refers to masturbators as “sinners”, and few modern medical textbooks would cite the book of Genesis as a source. But these might be more fig leaves against controversy. Krafft-Ebing is clearly fascinated by these people, and includes copious case notes on sadists, masochists, fetishists of feet and leather and furs, and exponents of rougher trade.

Case 42. A married man presented himself with numerous scars of cuts on his arms. He told their origin as follows : When he wished to approach his wife, who was young and somewhat “nervous,” he first had to make a cut in his arm. Then she would suck the wound, and during the act become violently excited sexually.

The literary work of Baron von Sacher Masoch and the Marquis de Sade are also mentioned. The latter’s works were banned at the time and very hard to find, so I wonder how Krafft-Ebing came to know of them.

Taxil (op.cit.)gives more detailed accounts of this sexual monster, which must have been a case of habitual satyriasis, accompanied by perverse sexual instinct. Sade was so cynical that he actually sought to idealize his cruel lasciviousness, and become the apostle of a theory based upon it. He became so bad (among other things he made an in- vited company of ladies and gentlemen erotic by causing to be served to them chocolate bon-s which contained cantharides)that he was committed to the insane asylum at Charenton. During the revolution of 1790, he escaped. Then he wrote obscene novels filled with lust, cruelty, and the most obscene scenes. When Bonaparte became Consul, Sade made him a present of his novels magnificently bound. The Consul had the works de- stroyed, and the author committed to Charenton again, where he died, at the age of sixty four.

(Is this historical tidbit true? Probably not. Sade published Justine and Juliette anonymously, he wouldn’t have drawn attention to himself with a personal gift of them to Napoleon. Sade was almost destitute at the time Napoleon became Consul anyway, and could ill have afforded expensive gifts. Napoleon committed Sade to Sainte-Pélagie Prison and then Bicêtre Asylum, it was his family that had him moved to Charenton. “Taxil” is likely the proven fraud Leo Taxil.)

Hiram Maxim and Mikhail Kalashnikov lent their names to guns. Sade and Sacher Masoch lent their names to diseases (or so Krafft-Ebing considers them). But that’s the issue at the heart of it all: what’s a disease?

Krafft-Ebing doesn’t seem to know of Darwin, but he gets basically to the same place. Basically, humans have a thing called fitness. We are supposed to survive, and make more of ourselves. Things that get in the way of doing either thing are diseases.

The state of liking blue over isn’t red is not a “disease”. Even if this preference was caused by a brain-controlling bacteria, we wouldn’t call it a disease, assuming that was all it did. It doesn’t impact our fitness.

But male homosexuality is clearly a disease, by a Darwinian standpoint. It reduces reproductive fitness by something like 50-80%. Most would object to calling, mostly because “disease” also has a lot of connotations (that it’s infectious, that it should be cured, etc). I don’t agree. Humans are partly reproduction machines, but also something more: we have a consciousness and a higher goals. There’s nothing inherently wrong with actions that clash with evolution’s “design”, which was largely shaped by chance anyway.

Krafft-Ebing notes that many gay men seem to have artistic gifts.

In the majority of cases, psychical anomalies (brilliant endowment in art, especially music, poetry, etc., by the side of bad intellectual powers or original eccentricity) are present

Suppose that’s true. Would that be a bad disease to have if you deeply desired to be an artist (and lived in a world of in-vitro fertilization?)

I regard homosexuality as a “wrong note” in Darwin’s musical score. Just because something’s technically wrong doesn’t mean we have to regard it as a thing to be fixed. No musician would call a piece of music flawed because it uses non-diatonic notes. Jazz musicians, for example, speak reverently of “blue notes”, which are pitched differently from standard. It all depends on the larger context. Technical deviancy doesn’t imply moral deviancy.

In some cases, the pre-modern viewpoint aligns more closely with the 21st century’s one than it does with Krafft-Ebing. A medieval bailiff would have viewed sodomy (for example) as a choice. An expression of preference. Contemporary culture thinks it’s the same. Krafft-Ebing seems the odd man out by calling it a degenerative pathology.

Here’s another interesting footnote:

I follow the usual terminology in describing bestiality and pederasty under the general term sodomy. In Genesis (chap,xix),whence this word comes, it signifies exclusively the vice of pederasty. Later, sodomy was often used synonymously with bestiality. The moral theologians, like St. Alphons of Liguori, Gury, and others, have always distinguished correctly, i.e., in the sense of Genesis, between sodomia, i.e.,concubittis cum persona ejusdem sexus, and bestialitas, i.e.,concubitus cum bestia (comp. Olfus, Pastoralmedicin, p. 78).

The premodern world actually understood well that bestiality and pederasty are distinct things. It with the Victorian world that blurred them into one undifferentiated sex act. A useful reminder that mankind can seem to progress scientifically, while in fact drawing blinds tighter around the truth.

Sade seems like a good place to end on. “It is a danger to love men, A crime to enlighten them.”

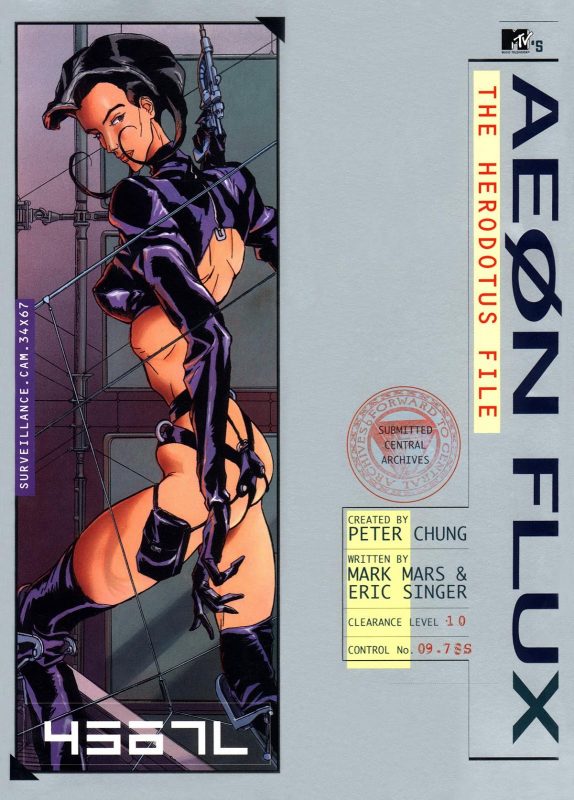

“I have been accused of caring nothing for the truth, but on the contrary, I value the truth so highly that I make sure it is hidden away someplace safe, where it is not soiled by dirty hands, embarrassed by prying eyes, or worn out through overuse.” – Chairman Trevor Goodchild

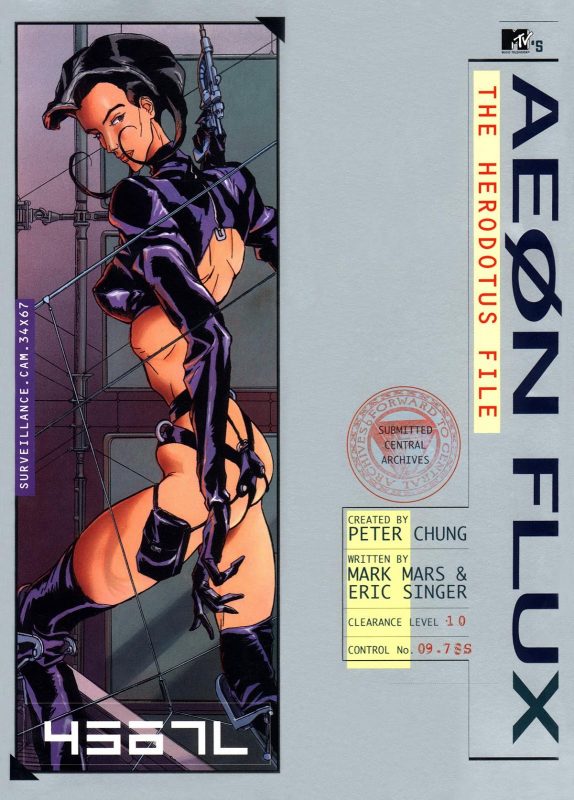

Aeon Flux is an animated exploration of psyche and politics. It’s a hard show, a cult hit where “cult” rings truer than “hit”, and it raises questions that carbon-based minds are ill-equipped to answer.

Casual viewers of the show can’t let go of the idea that Aeon Flux’s ambiguities are actually puzzles with solutions. Why are Monica and Bregna fighting? Were Aeon and Trevor ever in a relationship? We’re not supposed to know the answers to these questions, and episodes like “Utopia or Deuteranopia?” (featuring a deluded disciple who painstakingly “deciphers” his master’s encoded notes, only to learn they’re garbled madness) deride you for caring. But it’s still the typical line of analysis Aeon Flux receives: witness this grueling interview where Peter Chung is asked whether Aeon is a robot, a cyborg, or a clone. I mean, she keeps dying and coming back to life and surely there’s a rational explanation for that, right?

In 1995, MTV’s publishing arm decided to explain Aeon Flux’s universe once and for all – something like The Star Fleet Technical Manual may have been the model – and commissioned a few writers to create a book. I doubt they wanted anything like the Herodotus File, but they still put it in print. It was reissued in 2005 to tie in with the craptacular Charlize Theron movie.

It’s framed in a clever way: as a dossier from Bregna’s internal police. It’s a little like The Screwtape Letters, written by bureaucrats for bureacrats, dripping with a mixture of pathological malice and corporate bullshit.

Basically, Bregnan leader Goodchild seeks to crush a heretical Monican movement that claims that Monica and Bregna were once a single state called Berognica, and the dossier provides rap sheets on all of Monica’s most feared operatives – including Atilda Ram, a 657lb belly-dancer who smuggles contraband inside the folds and orifices of her body, and Loquat, who can adopt any disguise or identity perfectly (even being two different people in the same room!), thus creating uncertainty about whether he/she even exists.

The most fearsome of these characters is Aeon Flux herself, whose interests include infiltration and domination. She does modeling on the side.

The conflict between Bregna and Monica is ultimately just a proxy war for Aeon and Trevor’s deeper, weirder struggle. They have the one of the most unique relationships I’ve ever seen in fiction. They pretend to want to kill each other but clearly don’t. They both ignore countless opportunities to pull the trigger. They care very deeply about each other in a way irreduceable to mere love or hate.

Basically, Trevor Goodchild is a benign Orwellian dictator. He’s not a villain, but he’s often misguided. He wants to progress humanity, and views morality as a constraining process. Or as he puts it: “one doesn’t want to be trapped into making a particular choice simply because it’s right.”

Trevor lives in the hell of every totalitarian dictator; he can’t tell the truth to the people, and his underlings deceive and backstab him in turn. The gulf between what he wants and what he gets is incommensurable. He seeks to build a rational, open society, without secrets, yet he exists in nest of snakes, unable to trust or connect with anyone.

Aeon Flux exists in a hell of her own. She’s free…which means she’s a slave to chance and consequence. She has the liberty of a moth in a flame. Her actions almost always have nasty, unforeseen consequences (both for herself and the people she cares about) and unlike Trevor she can’t even hide behind noble intentions. The reverse of hell is not heaven.

The Herodotus File was written by Mark Mars and Eric Singer. Mars is a colorful guy Peter Chung met at CalArts. He has done virtually nothing aside from Aeon Flux, but he created many of the show’s most electric moments (“ready for the action now, danger boy…?”) Eric Singer was a lowly production assistant who cold-called Chung one day. He is possibly the most financially and critically successful person ever associated with the show (he was nominated for an Oscar Award for American Hustle, and co-wrote an upcoming Tom Cruise vehcle).

The danger of a book like this is that it will talk the show to death. Aeon Flux discusses universal problems of censorship, surveillance, etc. This goes away when you specifically place it (as the movie did) in a particular point in time, such as the far future. Specifics are the enemy.

The book threads this needle by being completely ludicrous, far more comical than the show, and impossible to take seriously. But there’s a lot of wit and fun along the way. The book makes me wish the show had contained a little more of Mars and Singer’s humor to lighten the dourness.

Aeon Flux fans probably can’t trust one word of The Herodotus File. Peter Chung (who had little involvement) says it should be viewed as a work of propaganda or disinformation. Unreliable. It’s a window into the Aeon Flux world, but not an accurate one. Take it as seriously as brings you pleasure.