As a kid, I watched Beavis and Butthead with the understanding that they’d prove a fleeting pleasure. “Soon I’ll be too old for this crap and it won’t be funny anymore.”

I am now very, very old, and still waiting for that day to arrive.

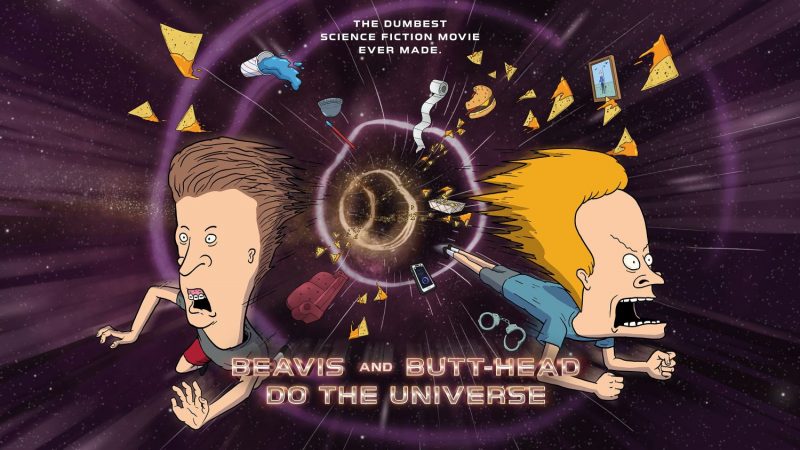

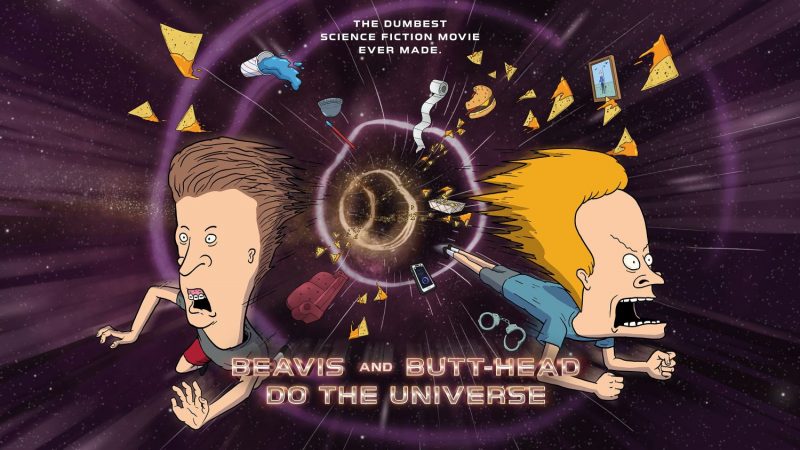

Maybe Mike Judge is a genius, or maybe B&B is so simple that it’s impossible to screw up, but the formula continues to work after thirty years. Beavis and Butthead are still two idiots who stumble through life mouth-breathing and misunderstanding everything that happens to them, and that’s all they will need to be. If only life was so simple for the rest of us.

The plot involves Beavis andButthead literally failing upward. After trashing a science fair (“Did we win the science fair?” “Even better, Beavis. We kicked its ass.”), a judge orders them to attend space camp for at-risk youth. An astronaut sees them, believes they are naturally gifted astronauts (a recurring plotline of B&B is the adult who mistakes them for secret geniuses), and takes them into orbit to study a black hole approaching Earth. In space, they create havoc, fall into the black hole, and emerge in the year 2022.

There’s the obligatory larger plot about government coverups and an incipient apocalypse, but the bulk of the comedy comes from them interacting with this new, strange world. Beavis thinks Siri is an actual woman and sexually harasses her. Later, the duo wander into a college class, are told that they have “white male privilege”, and start using that as carte blanch to do whatever they want. “Step aside please. We have white privilege.”

A 4channer once proposed a movie idea: a generic 90s bully time-travels to a modern high school full of furries and tenderqueers. B&BDTU is almost that movie. Aside from being funny this solves the main problem with the characters: they’re so indelibly a product of the 90s. What’s B&B’s main form of entertainment? To sit on a couch watching TV. Few kids do that anymore. They were further characterized by their love of heavy metal, which hasn’t been a mainstream force in a long time.

The Simpsons never knew how to upgrade its stock 90s setting into the modern age, but Mike Judge draws attention to the cultural gap. His duo is now more oblivious than ever.

There’s lots of bite in Judge’s comedy but no real cruelty. He isn’t mocking anyone except Beavis & Butthead, and even that’s not true mockery. The show was always a parody of boomer paranoia about Generation X (that they’re morally vacuous retards who just want to stare at bouncing boobs on MTV all day). To think Beavis & Butthead exists to ridicule Generation X is as misguided as thinking blaxsploitation exists to ridicule African Americans. And even if they’re figures of fun, so what? Beavis and Butthead are immune to mockery. That’s their power. Deplore their lack of morality, and they’d simply wheeze-laugh. “Heh heh…you said ‘oral’.”

And that brings me to an insight I had about Beavis and Butthead.

In the 17th century, a philosophical debate raged about the nature of mankind. Are humans endowed with an innate moral sense (Shaftesbury), or are we natural savages who must be disciplined by an external force such as civilization (Hobbes)?

In the 20th century, evolutionary theory offered a new answer: we’re both.

Imagine that humans come in two varieties: nice guy and bully. When a nice guy meets an bully, the bully wins. But if bullies become too common, nice guys gain an advantage (because bullies waste time picking pointless fights with each other while nice guys don’t). Over time, an equilibrium of nice guys to bullies is found (attach numbers to this simplistic model and you even calculate the exact ratio). The point is, you wouldn’t say that humans are naturally nice or naturally bully, you’d say that our species is split between two competing strategies. This is the insight of John Maynard Smith’s hawk/dove theory.

It occurs to me that Beavis and Butthead occupy one half of a hawk/dove strategy. The fact that they’re stupid and selfish isn’t a failing, it helps them. David Van Driessen is moral and empathetic, but this gets him exploited by Beavis & Butthead at every turn. Tom Anderson is conservative and proud to be an American, even after his country literally rapes him in the ass. Likewise, the social justice warriors have an elaborate set of shame-based social theories that Beavis & Butthead promptly weaponize against them without even knowing they’re doing so. It’s like intelligence and all its fruits (morality, empathy, time preference) is actually a harmful virus, and only Beavis & Butthead are immune.

I’m probably overthinking things myself. B&B is a fictional show. Whenever the idiots win, it’s because a writer made it so. But I still think B&B is pointing toward a real thing: intelligence is a virtue, but not a universal virtue. In a universe of rippling chaos, sometimes it’s the stupid who win.

Invest wisely and your portfolio will grow 9.89% YOY. Meanwhile, an 80 IQ truck driver just bought a lottery ticket and made a 133,333x return in five minutes. In the long term, intelligence wins out, but in the short term, the winners are usually stupid. And sometimes, the short term is all that matters.

Christopher Columbus’s voyage to the Indies was only somewhat less moronic than Beavis and Butthead going to space to get laid. But it led to the Columbian Exchange, the historical event of the millennium. Who knows, maybe the world really will be saved by a man with a T-shirt pulled up over his head, screeching about TP for his bunghole.

The Pixies are alt-rock’s dark matter: invisible, but they bend the universe around them. The 90s are inconceivable without their music. They laid the founding stones for Seattle grunge, 3rd wave punk, 90s glam revival, and indie rock, but they couldn’t lay the founding stones for their own careers. Other bands broke big. The Pixies just broke up.

“Why didn’t the Pixies become more famous?” was once a popular column brief in the alternative press. Too early? Too weird? Not enough MTV videos? Wrong place? Singer too fat? Bassist too lady? Whatever the truth, their gold and platinum certifications were awarded long after they broke up, after an unpaid PR campaign on their behalf by the likes of Kurt Cobain and David Bowie. The Pixies are to Gen X what the Velvet Underground were to baby boomers: more famous as musical corpses than they ever were as a living, active band.

On their records they merged into a wall of sound with a single performer sometimes punching through, perhaps one of Joey Santiago’s fierce, singing leads, or Black Francis squalling bloodily, like a thundercloud made of dripping meat. Their lyrics were minimalistic and filmic, owing more to visual language more than prose. Other bands wrote songs about being sad: the Pixies wrote about having a broken face. They approached subject matter obliquely and orthagonally: if they were a chess piece, it would be the knight. Some Pixies songs make you feel alienated. Others conferred a sense of cosmic understanding. Their best songs made you feel both at the same time.

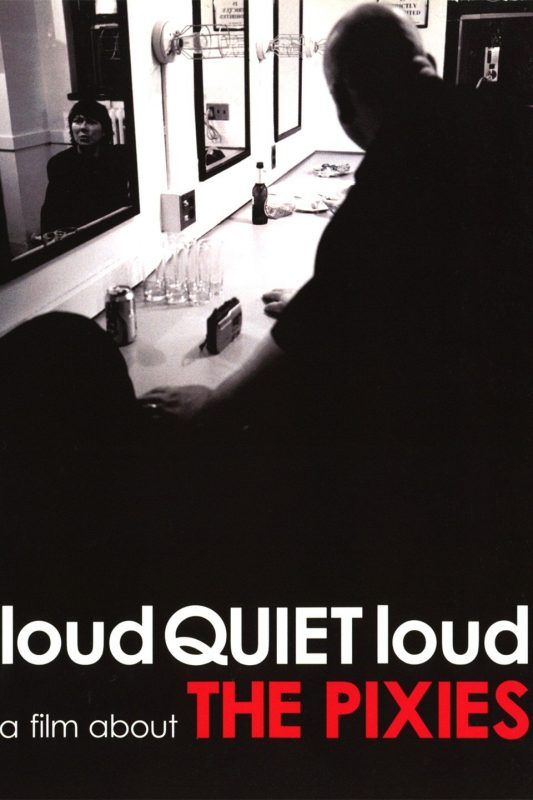

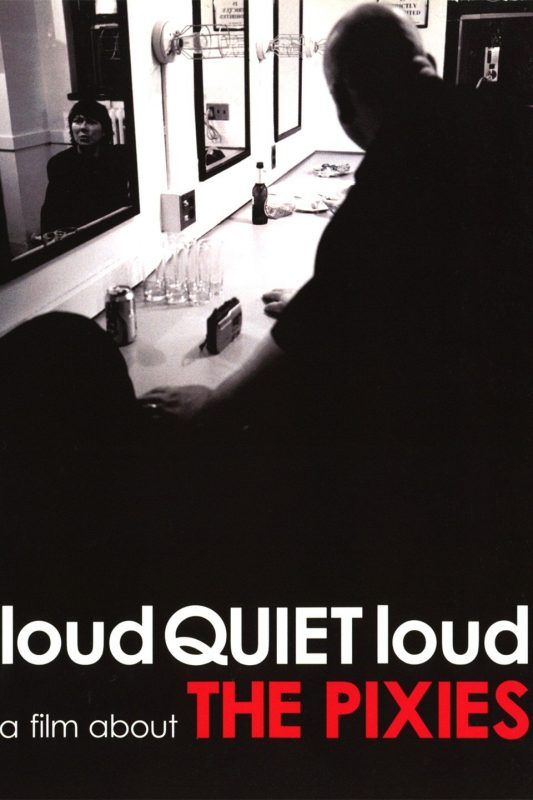

In 2003, rumors started crackling that the Pixies would soon reunite. The next year, a string of sold-out shows were announced. loudQUIETloud is Matthew Galkin’s 2006 documentary of their performances and some of the circumstances leading up to it.

Documentaries need storylines, and “legendary band reforming” has one that writes itself. Are the Pixies too old? Can lightning strike twice? Do they still have “it”? Are they still relevant in a world that’s changed beyond recognition (in 2003, “alt rock” now meant Evanescence, Linkin Park, and Nickelback)? Also, why do it at all, when there’s ample evidence that they don’t particularly want to?

It’s clear in the film’s first few minutes that the Pixies reunited because of money.

Francis’s solo act (can we admit that The Catholics was his solo act?) was stuck in a rut. Release an album on some indie label, get a 6/10 from a Pitchfork nerd who raves about how cool the Pixies were, make a pittance touring bowling alleys and phone booths, repeat. Santiago and Lowery never even had a rut to get stuck in: their faces hold the sullen desperation of Oliver Twist asking for more gruel. Kim Deal had arguably weathered the post-Pixies years the best (“Cannonball” was the crossover MTV smash her former band had never had), but she was fresh out of rehab, and also had the commercial failure of the third Breeders’ album hanging over her head. Santiago comes up with a funny name for the tour: The Pixies Sell Out. Or it would be funny if it was ironic.

Lowery is blunt about the situation. He states that although royalties from the Pixies had more or less supported him through the nineties, by 2004 this was no longer true. Four years previously the domain Napster.com was registered by a NEU student called Sean Parker, and suddenly the cool thing to do with music was not pay for it. The industry began collapsing. This is the reason why every venerable rock act was (and still is) touring like devils into their 60s and 70s. Live music became the backbone of the industry: you still can’t download a band into your living room on Napster. I regard Sean Parker, who can’t play a note, as one of the defining figures of 21st century music, scarcely less significant than Guglielmo Marconi.

Continuing the legacy of the Pixies is a daunting task on the face of things. We see Black Francis looking terrified, like a man nerving himself up for a 10,000 ft skydive. He repeats affirmations on a couch. “I can do it! People like me! I’m cute!” (Two out of three isn’t bad.) We also see Kim anxiously fretting (in multiple senses), worried that she’ll biff notes and look like an aging fraud on stage.

“Why are they back?” is one question. “Why did they split?” is another, and the film never addresses it, except at slant angles.

The breakup of the Pixies is another big mysteries. “Francis and Kim were fighting” is the usual non-explanation proffered…but why did Santiago and Lowery leave? Part of a good documentary is establishing the leads as characters. Is Black Francis a chill, laid-back teddy bear? Or a slightly sinister, controlling figure? The film never comes down on side or the other, allowing the viewer to make up their own mind. But as Francis himself said, where is my mind?

We sense the rifts between Francis and Kim, which don’t seem to have closed with time. Kim rides on a separate bus to the others, apparently working on material for a new Breeders album. There could be ample reasons for this (ranging from “her desire to stay sober” to “her commitments to her sister” to “she would rather give herself a cervical exam with a trench shovel than ride on a bus with Black Francis”) but the film doesn’t settle the issue. Will there be new Pixies music? Francis seems hostile to the idea. He’d rather talk about his next solo album. When Kim is asked the same question, she responds with “you’re demanding answers to questions that have no answers.” (Sadly, an answer finally came in 2014, when the Kimless Indie Cindy hit a remainder bin near you. It got a 2.5/10 from Pitchfork, which doesn’t even seem possible.)

The documentary’s title is a reference to the infamous loud/quiet songwriting mode of alt-rock, where a soft verse is contrasted with an explosive chorus (“Smells Like Teen Spirit” being a canonical example). But the style here is more quietQUIETquiet. It’s cleanly shot and well-directed, but you still need to listen hard to gain any insight on the Pixies…same as ever, in other words.

Mid-tour, we see Lowery going on a bizarre rant in Kim’s dressing room. Soon after, the band falls apart during “Something Against You”, with Lowery apparently having no idea what song he’s playing. He claims that he couldn’t hear the stage monitors, but Santiago believes he was on drugs. Kim and her sister are visibly having trouble themselves, with terse conversations about whether they can stay dry during a nine-day stopover in NYC.

There are very few scenes of the Pixies interacting with each other, and it always has a weird vibe. Their chemistry is awkward and full of fake laughter. They’re trying to be friends, but there was a reason this band stopped working out in 1993, and probably most of those reasons still exist. We wonder if they’d even want to be in the same room if the checks stopped clearing.

There are also happy times. Moments when the band clicks on stage. Scenes of Santiago and Francis hanging out with their families. The reactions of fans is incredible to behold – however cynical the Pixies reunion might seem – the elation it produced was real. The documentary ends with a Kim Deal superfan being inspired to pick up the bass guitar herself. The Pixies are dark matter, but there’s light matter in the universe, too.

But the stakes in this reunion seem so low. The Pixies are selling out shows…but they’re playing clubs and theaters, not arenas. Fans swarm them for autographs…but it’s ten or twenty people, max. The Pixies weren’t that big in the 80s and they’re no bigger now, even after their innovations have percolated throughout all of mainstream rock. These guys are scrapping hard, not to regain a seat on rock’s throne, but to obtain a nine-to-five income. But is there anything more quintessentially alt-rock?