In ’42, German forces advanced into Russia in the depths of winter. They were confident, thinking their foes weak and in retreat. They were about to be destroyed.

This was 1242, when a young Russian prince lured an army of Teutonic knights and Estonian auxiliaries onto the frozen surface of Lake Peipus and slaughtered them on the ice. Alexander Nevsky’s victory is remembered in Russia as Ледовое Побоище, or Icy Massacre, and might be history’s only naval battle to not involve a single boat. It ended the Teutonic Order’s pretensions upon Novgorodian territory and turned Nevsky into a national hero, sainted in 1547.

Heroes never die. Even when they pass away, something of their essence remains in the national heartwood, inspiring others through the centuries. Seven centuries after Nevsky died, history began to loop back on itself. A prisoner in Germany wrote a book about the future. He was ambitious; mad. He wanted Europe in flames, and a German empire atop the bones of a Russian one. Eight years later that man was both free from prison and Chancellor of Germany. Armies were gathering, and Russia needed heroes once again.

It was inevitable that a film about Alexander Nevsky’s life would be made: a Russian patriot fighting German Catholics was a perfect propaganda coup. Also, Nevsky had died a very long time ago, and we don’t know much about him as a person. This allowed a director freedom to “interpret” him as whoever they wanted, as well as freeing him from troublesome contemporary politics (unlike the Russian generals who had fought Napoleon…on the side of the tsar).

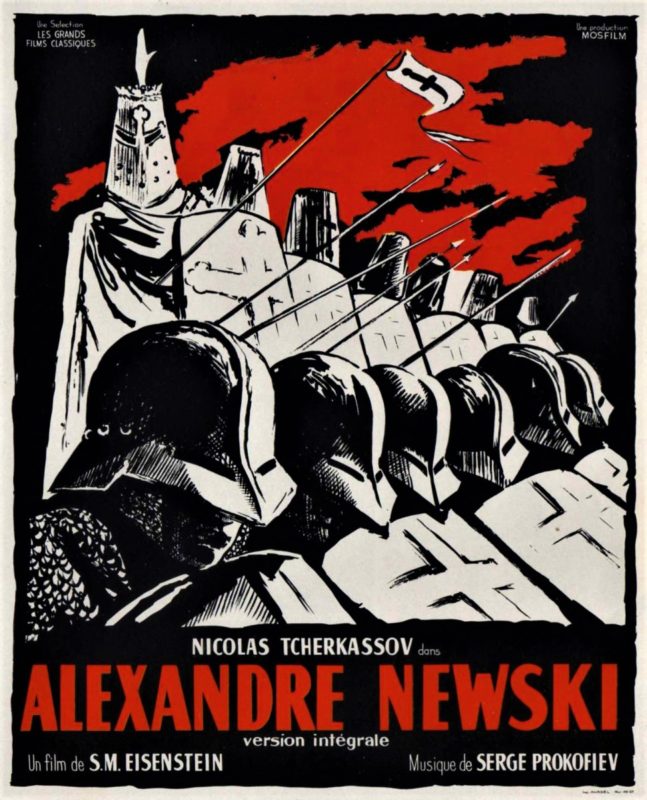

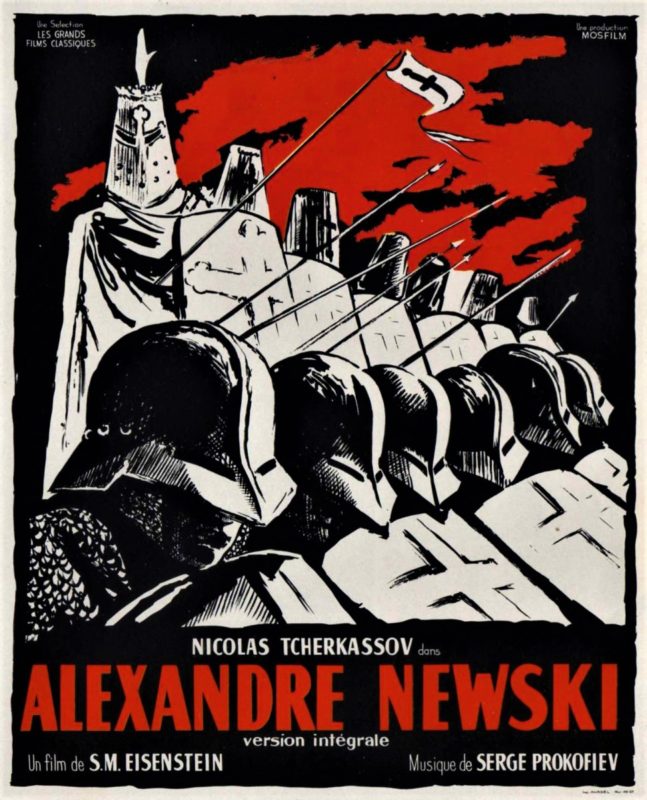

Alexander Nevski was directed by Sergei Eisenstein, with many asterisks and scare-quotes around “directed”. Soviet culture regarded artists as civil servants; if you could write a poem or paint a picture you were expected to do so for the state (and under the state’s supervision). Eisenstein was regarded as suspect when he made the film: he’d spent years living in the west, only returning after what appears to be blackmail. His previous film Bezhin Meadow had failed and earned him a public reprimand. His friends were being arrested, and he soon suspected that the NKVD was shadowing him. Eisenstein probably saw Alexander Nevsky as his last chance, and resolved not to put a single foot wrong. It’s debatable to what extent it’s “his” movie.

It was filmed in 1938 and produced by Mosfilm, with the final cut receiving some additional tinkering by the Party. You could almost give Joseph Stalin an editing and production credit. The picture gained final approval from the State Committee for Cinematography and was released on December 1938, although it hit a snag when when the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact turned Russia and Germany into momentary allies. Ultimately it was a success, rescuing Eisenstein’s reputation and gaining him a new following abroad. It’s a huge, huge film. Irrefutably part of the canon.

But is it good? Difficult question. As journalist Chet Flippo said after seeing a Queen concert, it “got the job done. I’m just not sure what the job is.”

As a movie it’s a disappointment, featuring rancid acting, a dull story, and sententious touches (medieval Teutons that wear swastikas) that turn its historical setting into chopped liver.

It’s a relic from a bygone age when film was theater’s little brother: get ready for ponderous cinematography, pounding melodrama, shouty brow-furrowing performances, and a total lack of subtlety. Your enjoyment of Alexander Nevski depends on whether you think shots like this are dramatic or silly.

Nevsky is played by Nikolay Cherkasov, whose impression of a wooden board is second to none. His acting skills are suffocated by the role he’s playing: he’s Alexander Nevsky, Great Hero of the Motherland. He doesn’t have a love interest because his love is Russia, he can’t show weakness because Russia has no weaknesses, he can’t fart because that would be like Russia itself farting, etc…

Sergei Prokofiev’s score is acclaimed but I didn’t enjoy it: its shifts from movement to movement (with wildly different moods) sound weird and inorganic next to modern film scores. It’s probably great. I just can’t find a way into it. The subtitled dialog contains deathless Yoda-esque lines such as “They are strong! Hard will it be to fight them!” that hopefully flow better in the original Russian.

Eisenstein (as noted by Roger Ebert) sometimes made films that ascended directly to “great” without actually being good. Alexander Nevsky feels like that sort of movie: it has a spot on the film school curriculum but maybe not in the hearts of many students. It’s a 50 foot colossus with a clown shoes and a big red nose. Huge, important, towering above the landscape…but at the same time, it’s hard to take seriously.

In short, it’s a film of its time. In nearly every scene, shot, and frame, there’s something that jolts me out of the picture. The film at its best is a 1930s version of James Cameron’s Titanic, lavish and expensive, carrying the heft of history, with some innovative and somewhat impressive filmmaking techniques all built around a massive effects-driven set piece. At its worst, it’s patently absurd and laughable.

That’s one way of looking at Alexander Nevsky. The other is as a source of patriotic hope.

The darkness in the West hangs over all of this. You have to remember the circumstances of its production, who would have wanted to see it, and why. Many of Alexander Nevsky’s apparent flaws disappear when you watch it the way you’d listen to a national anthem as a patriot, or attend a church service as a believer.

The broad characterization and black-and-white morality are like anchors, points of stability in an unstable world. The Teutonic Knights are vile (there’s a horrible scene involving infants being thrown into a fire), but so were the real life Nazis. The film runs highlighter over Russian pride and German evil, relating everything back to the USSR’s contemporary circumstances. The historical garb is thinner than rice paper. I don’t think it was meant to be judged as a movie.

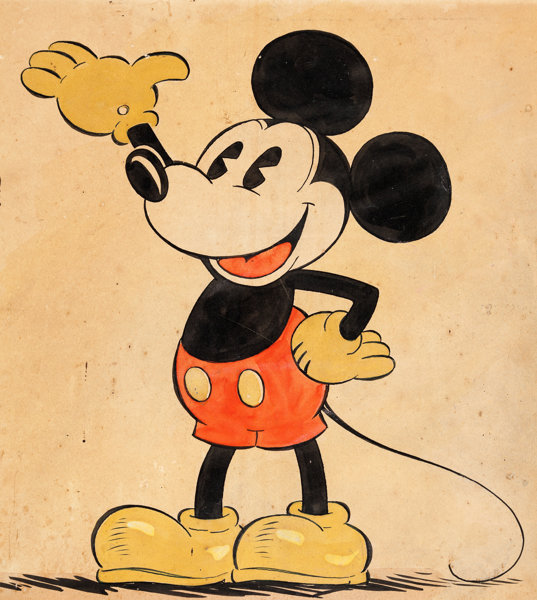

Even the film’s camp moments are interesting. At the start we see a Mongol chieftain offering Nevsky a command position in the Golden Horde (which is declined). He’s a silly fat man with a top-knot that looks like Mickey Mouse’s ears.

I am no expert, but I can’t find a photo of a traditional Mongolian (or Chinese) hairstyle that looks like that. It seems unique to the film. I half suspect we’re supposed to think of Mickey Mouse’s ears – the black cap contrasting with his pale skin completes the image. Mickey Mouse (like Alexander Nevski) is inseparable from one particular country: the United States.

Does the Mongol Mouse represent capitalist America in the film? Just as Nevsky represents Russia? That would explain the ominous dialog where Nevski says that although the Mongols are a threat, the Germans are worse and must be fought first. “The Mongols can wait, methinks. We face more dangerous foes.” The difference, Nevsky goes on to explain, is that Mongols are greedy and can be placated with gifts (like capitalists), while the Germans are evil, destroying all that isn’t them (fascists). This anti-fascist angle, it must be said, now looks odd in light of how the Mongols are depicted as grubby savages, while Cherkasov is a tall, blond Aryan superman.

The rest of the film features more blatant pro-Soviet propaganda. Nevsky butts heads with with wealthy boyars (representing kulaks) and priests (representing…) who don’t understand the danger, want to appease the enemy, etc. Fortunately, Nevsky has the people on his side.

This isn’t even pseudo-history, it’s fan-fiction, like a teenage girl making Harry and Draco kiss. The real Alexander Nevsky was a rich aristocrat who took monastic vows. He wasn’t any kind of rabble-rousing working class hero (let alone an anti-capitalist or anti-clericalist). This is Russia’s 1930s political milieu projected seven hundred years into the past. But this is like noticing that Americans depict Jesus as white: it misses the point. Alexander Nevsky isn’t supposed to depict history except in a superficial way. It’s doing something more elemental, issuing marching orders to a nation.

What about the battle scene?

The final third of the movie is eaten up by an extremely long battle involving elaborate staging and hundreds of extras. The rest of the movie seems draped across this set-piece like a threadbare set of clothes (again, Titanic). When the horns blare and the massed columns of infantry advance onto the ice, you forget about everything that happened before. It’s its own self-contained universe.

The scene is groundbreaking – literally groundbreaking, it ends with an army falling through Lake Peipus – and ranks among the most thrilling moments yet seen in a movie. How did it take just forty years to go from Fred Ott’s Sneeze to this? Even today, the battle looks fairly good. Almost any time you see a motion picture featuring a cavalry charge – be it Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings, Mel Gibson’s Braveheart, or Sergey Bondarchuk’s Waterloo – it’s trying to look like Alexander Nevsky, consciously or otherwise.

Yes, you can sort of tell that the actors are being filmed under a bright sun on a hot day, but in black and white it’s not obvious. Films have something called “day for night” (a “night scene” that’s clearly not at night). Alexander Nevski went one further: hot for cold. Sand is used in place of snow. Huge sheets of broken glass are used in place of ice. The incredible thing is that it works.

It must have taken a staggering amount of money to film the battle. The costumes, props, and so forth look perfect, and there are hundreds of them. Within a few years, Russians would be facing the Germans with empty rifles, tanks without radios, etc. There’s a grim irony to the fact that (based on the opening weeks of Operation Barbarossa) the USSR was better at fighting a fake war than a real one.

It has some dated elements. Eisenstein wasn’t able to capture the violence and kinematics of an actual battle. Blows are half-hearted. People fall over dead for no reason. Horses are perfectly calm where they should be white eyed, terrified, and spraying foam.

This moment made me laugh. It was like a Keystone Kops gag.

The sheer length of the battle wore me down. Just shot after endless shot of men swinging swords at enemies conspicuously out of frame. I’ll admit that after twenty minutes of this, I wasn’t overjoyed by the prospect of twenty more.

However, the battle ends on an striking visual: the beleaguered Germans collapse the ice with their weight and drown. This is apparently fiction – no contemporary accounts describe such an event – but it’s good, effective filmmaking, breaking the tedium of the battle and providing effective closure to the ice scene. It’s Chekov’s gun in the end. Put a gun on the set, and it has to get used. Put an army on a a frozen lake, and they have to fall through.

Many nations have legends of sleeping champions (Portugal’s King Sebastian, Britain’s King Arthur, Germany’s Frederick Barbarossa) who will return to fight for their homeland in its hour of need. But the atheistic USSR didn’t believe in such fairytales. They forced Nevsky back to life, through the magic of cinema. They probably thought they had to.

It’s a little hard to recommend the entire movie, although the battle is worth watching. Alexander Nevsky does not escape the time its in. You have to take it for what it is, a propaganda tool for a desperate nation facing desperate times. Seen with this in mind, it has a chilling power. Thunderclouds seem to hang above it. Walls of tanks clank in the background. Ahead lay a nightmare: a war so awful that historians disagree not just on how many Russians died, but how many million. The battle is inseparable from the mechanical savagery of Stalingrad and Kursk. The burning children reminds of the Holocaust.

Few films gain so much from their context, and few films have a context this awful. Alexander Nevsky is like a battle standard overlooking a battlefield. It’s just a crude image of a lion, fluttering in the wind. But underneath that lion are rivers of gore, shattered bones, smashed helmets and vambraces, cries of the wounded, and feasting crows.

Most stories have an endoskeleton: a theme that lies inside them like a set of bones. Sometimes it’s the same bones as another story: remove the flesh of plot from Lord of the Rings or Star Wars and you’ll find the skeleton of Campbell’s Heroic Journey. Autopsy a random romance novel from the 70s or 80s and the skeleton will be the Three R’s (Rebellion, Ruin, Redemption). Some stories are thin, their thematic skeleton close to the skin, while others are fat: you have to delve deeply through the narrative’s flesh, muscle and organs before you find it.

But then you have stories that have exoskeletons: their bones are on the outside. The theme sits on top of everything else: there’s no need to autopsy such a body to discover its skeleton, it’s there in plain view, and often it’s the only thing you see.

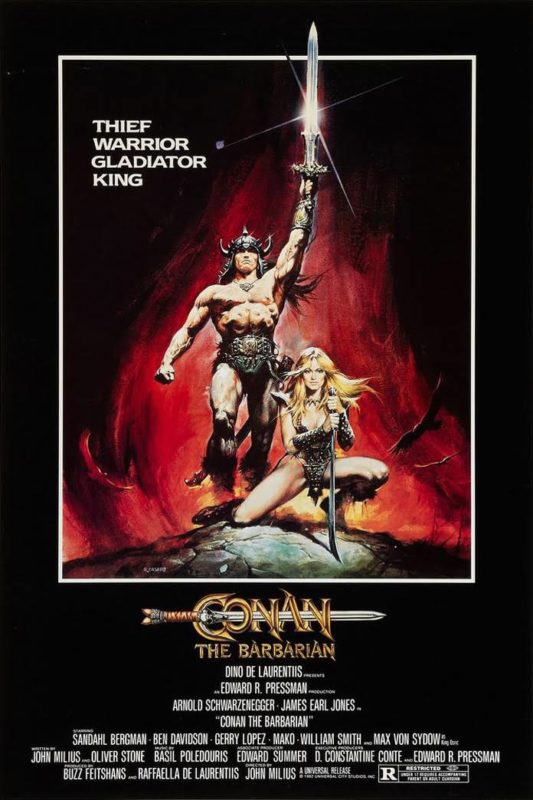

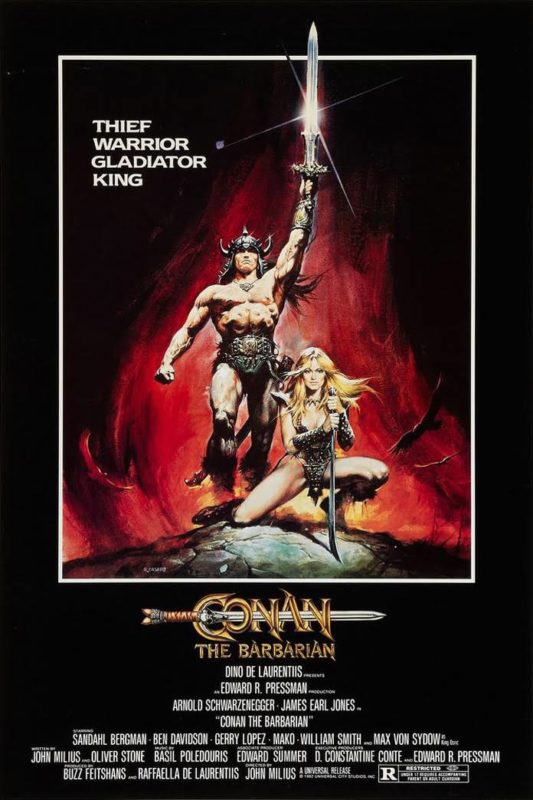

Conan the Barbarian is an exoskeletal movie, virtually all theme and zero story. Every character is an archetype, every plot point is as predictable as the movement of the stars, and the symbolism is very blunt – a Freudian psychoanalysist would suffer coronary thrombosis comparing swords to phalluses in this movie. It’s a stirring and powerful experience. Every scowl, drawn blade, and bombastic orchestral sting exists in service of myth. Conan the Barbarian is held high by mighty iron pillars of theme.

In ancient Hyboria, a tribe of Cimmerians is massacred by cultists of a dark snake god, and a blacksmith’s son is taken captive and sold into slavery. He grows to adulthood chained to a mill, revolving in endless circles. Somehow, this turns him into a muscular titan. Real slaves are skinny, haggard, and old before their time. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s body was clearly built by gym workouts, steroids and protein shakes. But that doesn’t matter, because the thematic through-line (“Conan has performed great labors and become mighty, that he might escape and seek vengeance against Thulsa Doom.”) vetoes logic and realism.

Conan the Barbarian is not faithful to any one Robert E Howard’s story (the Conan of this movie has more in common with Kull the Conqueror), but it’s faithful to Howard’s storytelling. It’s the sort of thing Howard would have written.

Howard, more so than the others of the “Weird Three” (Lovecraft and Smith) was indebted toward the lower side of pulp. He wrote action well, and his stories rely on energy and speed – they’re as streamlined as the mechanical rabbits that greyhounds chase. This also led to a certain carelessness. Lovecraft and Smith would carefully construct a setting: Howard threw up plywood constructs and then smashed them beneath stampeding Hyborian horses. Here’s what I mean:

Chunder Shan, entering his chamber, closed the door and went to his table. There he took the letter he had been writing and tore it to bits. Scarcely had he finished when he heard something drop softly onto the parapet adjacent to the window. He looked up to see a figure loom briefly against the stars, and then a man dropped lightly into the room. The light glinted on a long sheen of steel in his hand.

‘Shhhh!’ he warned. ‘Don’t make a noise, or I’ll send the devil a henchman!’

The governor checked his motion toward the sword on the table. He was within reach of the yard-long Zhaibar knife that glittered in the intruder’s fist, and he knew the desperate quickness of a hillman.

The invader was a tall man, at once strong and supple. He was dressed like a hillman, but his dark features and blazing blue eyes did not match his garb. Chunder Shan had never seen a man like him; he was not an Easterner, but some barbarian from the West. But his aspect was as untamed and formidable as any of the hairy tribesmen who haunt the hills of Ghulistan.

‘You come like a thief in the night,’ commented the governor, recovering some of his composure, although he remembered that there was no guard within call. Still, the hillman could not know that.

‘I climbed a bastion,’ snarled the intruder. ‘A guard thrust his head over the battlement in time for me to rap it with my knife-hilt.’

‘You are Conan?’

‘Who else? You sent word into the hills that you wished for me to come and parley with you. Well, by Crom, I’ve come! Keep away from that table or I’ll gut you.’

The setting is ancient, but the prose is modern. The dialog sounds like it’s from a hardboiled detective novel (you almost expect Chunder Shan to offer Conan $25 a day, plus expenses), and anachronisms like “the devil” and “parley” sit oddly in a tale of a vanished age.

For better or worse, this how the movie goes, too. Take away Conan’s mythic grandeur, and what’s left? “A rich man hires a tough to rescue his wayward daughter.” That’s a detective story. In fact, it’s the detective story. It’s the same basic plot as The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler and countless others. Everything beneath the exoskeleton is pure pulp.

Likewise, the movie captures Howard’s eclectic setting. Low-budget grindhouse films had a reputation for shooting with whatever props and costumes were available (leading to movies about roller-blading samurai, etc) and Howard’s stories have a similar feel. In The People of the Black Circle (quoted above) we get a weird amalgamation of real-world cultures, and Conan likewise throws together Mongols, Vikings, Indians, and everything in between. As Zack Stenz once pointed out, the movie owes quite a lot to 70s California beach culture. The story, written another way, could be phrased as “a Venice Beach bodybuilder and his hapa buddy do drugs, get laid, and fight a cult that exploits hippies.” Gerry Lopez (Subotai) was a surfer friend of director John Milius. Most of the remaining cast are athletes.

Some roles are oddly cast, but the most important one – that of Conan – is dead on. No role has ever suited Arnold more, except perhaps the Terminator. His overwhelming physicality sells him as a mightly-thewed barbarian, and his uncertain, rumbling, learning-to-talk diction adds verisimilitude. When you listen to Arnold speak, you don’t doubt that you’re hearing the beginnings of human language.

There are depths to Conan, but the surface is predictable. Its characters are so archetypal that they can’t do anything interesting or surprising. All of their motives are clearly spelled out, and the viewer is never in any doubt about what will happen – what must happen. Some movies are like taxis, slyly taking you on the scenic route through town if you’re not watching the meter. Conan is more like a train, pulling into the station, then leaving at a certain time on a fixed path. And since Conan is hardly the first film to adapt such mythic material, the train’s travelling down a route you’ve seen many times before.

But most people consider regularity in their form of transport to be virtue, not vice, and maybe the same is true for stories. For the rest of us, Conan the Barbarian’s the perfect movie to watch if you’re twelve, or want to remember being twelve.

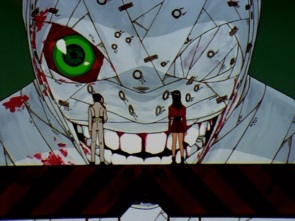

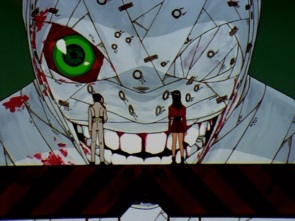

A goliath of the 90s. There are days when I think you could watch Akira, Perfect Blue, Redline, this, and then stop watching anime.

But it’s flawed! Few things this excellent contain so many problems. NGE is tonally disjointed: the early “monster of the week” episodes look cheesy next to the later psychologically-driven episodes. The plot is always unclear and often incoherent, full of mystifying exposition dumps (ep20: “We can surmise that Shinji’s body lost its ego border, and he’s floating in the entry plug in quantum form.” […] “All of the substances which composed Shinji are still preserved in the plug, and what could be called his soul exists there as well. In fact, his self-image is pseudo-substantiating his plug suit.”) that create far more heat than light.

The story – to the degree it’s comprehensible – is riven with logical issues and internal contradictions. NGE has plot holes that simply can’t be closed no matter how hard you try. Fans have been analyzing this show for twenty five years without success: utterly basic questions such as “what’s an Angel?” and “what’s [character] trying to do?” are still unanswerable mysteries that spawn 10+ page forum flamewars in their wake, with users quarreling over the definition of some Japanese word or conducting exegesis of an offhand statement made by Hideaki Anno in a fanzine interview.

It’s a credit to NGE that fans are willing to take the effort. It’s an indictment that they need to. There simply aren’t any answers to a lot of NGE’s questions: just provisional rules that change from episode to episode, and from media to media. Given that SEELE knows the truth of Kaworu’s identity, why do they tell him what’s inside Terminal Dogma in ep24? Why does he then act surprised at what he finds there? Why can’t he sense Adam’s location, the way Gaghiel can? Given that the Spear of Longinus can instantly kill an Angel, why doesn’t Gendo use it until the Arael battle? Why is SEELE so angry about losing the Spear when they can create replicas? Which souls are in which Evas? Which numbers belong to which Angels? Does Eva-01 come from Adam or Lilith? What’s with Gendo’s habit of sending out Evas one at a time to fight an Angel, instead of all at once? How is the Third Impact triggered? Anime in general creates a lot of fanfic. NGE all but conscripts you to make fanfic, because the only way the show makes sense is if you rewrite it.

Most NGE fans would concede that the show looks smarter than it is. All the allusions to Christian mythology and Freudian theory mostly just turn out to be decorative wallpaper in the end, unrelated to the show’s main concerns. Why are Ritsuko Akagi’s computers named after the Biblical Magi? Because it sounds cool: there’s no deeper meaning and there’s almost never a deeper meaning. Westerners wear shirts with Kanji letters without caring what they mean, and NGE does the same for the Western intellectual canon. This isn’t always true (there’s some surprising philosophical acuity at times), but NGE occupies an uncanny valley of fun. It’s too hard for people who just want to watch giant robots fighting, but has too many generic seinen elements for fans of highbrow anime like Serial Experiments Lain.

But NGE does a lot of things right.

At the risk of sounding ten years old, the fight scenes look great. Maybe too great – they were fires that burned through Gainax’s modest budget, forcing a restructuring of the show’s final two episodes that remains controversial to this day. Basically, Anno’s big innovation was to fuse the then-stale mecha genre with biology. The “eva” mechas (piloted by children such as Shinji Ikari as humanity’s last line of defense against dimension-crossing “angels”) are cyborgs created from the flesh of Adam, the first being. It’s strange how this tiny detail completely fixes the fundamental problem with mecha genre: you’re watching hunks of metal punch each other, which gets dull. Eva’s battles are visceral and satisfying. When a punch lands on one of Hideaki Anno’s nightmarishly-designed monstrosities, you wince: you feel the flesh being pulverised. No matter how outlandish or surrealist NGE becomes, it remains a gruesome mortician’s table of a show: focused on bodies and mortality. Being an eighty-foot giant is not a reprieve from suffering: it just means you rot all the more.

The visual design of the Angels is superb, and their variety allows NGE to have its fingers in many pies. Fights involving bipedal Angels have a glorious city-smashing kaiju/tokusatsu character, the insectile Matarael evokes the “giant bug” movies of the 1950s, the aquatic Gaghliel echoes It Came from Beneath the Sea, the space-based Angels could be read as references to Leiji Matsumoto’s spacefaring adventures, and the bodyless Angels allow for tense Outer Limits-style conflicts that are fought in a psychological or emotional domain. The bizarre Leliel stands out as a wholly unique creation – I’ve never seen anything like it before, either within anime or outside it.

The editing is also excellent, full of slam-bang intercuts, and deliberately jarring transitions. The abrupt black title cards alone are a NGE trademark. Anno has a talent for overstimulating the senses that can best be described as Artaudian: happy music plays over tragic events, we sometimes view shots from deliberately awkward angles, or lose contact with a scene just as we’re on the verge of understanding it. It’s very hard to be bored while watching NGE. The material on the screen is as infuriating and fascinating as an optical illusion or a mirage.

And although NGE often looks smart when it’s not, it’s also looks dumb when it’s not, too. Newcomers to the show (who might have been recommended NGE as a thinking man’s anime) are often struck by how it clings to the genre’s basest cliches. Partly this is because NGE rebuilt the industry in its image (Rei Ayanami and Asuka Langley Soryu were influential in establishing the kuudere and tsundere archetypes, respectively), but the more gratuitous fanservice moments were embarrassing even in 1995. The basic plot (a fourteen year old kid gets to save humanity in a giant robot while hot girls fight over him!) is wish fulfillment from a kid who gets bullied either too much or not nearly enough.

But as the show progresses, you soon see what Anno is doing: commenting on the cliches of mainstream anime. There’s playful subversion – the way the stale “harem” setup gets deep-sixed by an implied male-male relationship for Shinji, for example. The show as a whole reads almost like a knowing parody: it’s mocking itself, mocking you for buying into it. Most of the characters reach a fate that’s very out of line for their pre-set archetypical roles (the “mother figure” is quietly and cruelly destroyed, the tsundere’s psyche is snapped in half, etc), and this must have been intentional. Anno was gathering every up cliche and stereotype he could, and then throwing it all off a cliff.

He was right to. Anime is stylish and fun, but it can also be very limited. Its aesthetic choices will rise up around you like prison bars if you let it. Go on Crunchyroll and contemplate the sheer sameness of anime. How many shows are being made with exactly the same story? How many magical schoolgirls? How many harems? There are other ways of being, other stories to tell, and NGE embraces anime’s cliches just so it can destroy them publically in front of you, like the Inquisition burning heretics in an open village square.

Some have described NGE as “otaku-therapy“. I’m not sure that I’d go that far, but there’s a strong sense that Shinji is supposed to be you. NGE‘s final two episodes ram this home with startling force: how much of yourself will you give up to belong? Shinji is offered a choice to become part of a hivemind, or remain his own person. He makes his choice. Certain anime fans make theirs.

And NGE absolutely does have things to say about philosophy. It integrates Jungian theory (shadows, masks, the subconscious collective) and Schopenhauer (the Hedgehog’s Dilemma) into the plot in a way that makes sense and feels natural. It’s clearly made by someone intelligent – so how to explain the show’s sloppier plot elements? You’d almost wonder if NGE’s story even matters in the slightest, or if its plot is just more disposable-and-disposed-of cliche. By subjecting its plot to logic, we might be putting decorative furniture under a vice and hydraulic press. Yes, it shatters, but they were never the load-bearing part of the house.

In a breath, I would say that NGE entertains the casual viewer (“robots fighting each other, dude!”), disappoints the deep viewer (“the story doesn’t make sense!”), and entertains the really deep viewer (those who look past the story altogether, and view it as a kind of referendum on anime genre itself, as well as the toxic fanbase.) There’s a lot going on in NGE, and you have to look past battling robots to see it. It’s an anime almost impossible to stop thinking about. It raises issues that stick in your mind like particles of grit, refusing to leave. Grit is irritating and painful, but pearls are forged upon such.