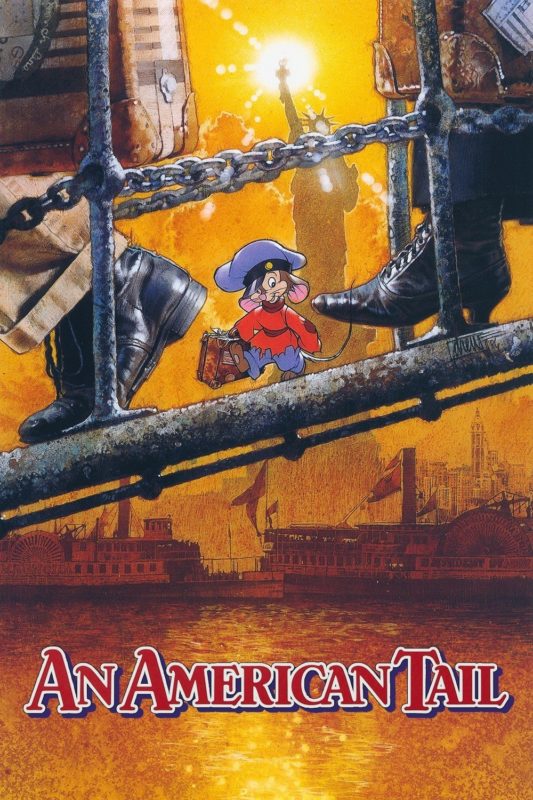

Movies about animals are legally required to have a pun in the title, and An American Tail walked so that Dog With A Blog and Alvin and the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked could run.

It’s one of the grim, high-concept films Don Bluth made after he left Disney. Secret of NIMH, An American Tail, and The Land Before Time are famed for their craftsmanship, but they’re tough sledding, darker than any Disney film except for The Black Cauldron. A lot of people remember these films as classics. A lot of them have forgotten that these films made them very scared or sad.

The setting is 19th century Russia. Fievel Mousekewitz’s family lives in a mousehole under a shtel, but then Cossacks burn down the shtel, while a gang of cats destroy their home. Tail is obviously an antisemitism parable, with mice representing (Jews and cats goyim). It’s setting is generations earlier than Maus, but it was still close enough for Art Spiegelman to ominously rumble about a lawsuit.

The opening scene is hilarious, with mice being chased around by fez wearing, black-mustached cats roughly the size of Shetland ponies. Their growls have been pitch-shifted down to half-terrifying, half-comical gurgles. If cats breathed radioactive fire, this would be a kaiju film.

The displaced Mousekewitzes board a steamer bound for America, where (they have been told) there are no cats. Fievel unwisely ascends to the fore-deck during a storm, is blown overboard, and eventually washes ashore on New York in a bottle. The rest of the film involves him looking for his family, along with some other complications.

Tail’s plotting is less surefooted than NIMH’s or Time’s. After the main drama is established (“Fievel has lost his family”), a huge number of supporting characters are dumped into the story – a friendly pigeon, a streetwise Italian mouse, a rabble-rousing agitator, a rich lady mouse, a back-slapping politician type, a helpful vegetarian cat, and more – turning the film into a top-heavy mass of character right when it needs to be racing into the third act.

I remember being confused when I first saw it. I couldn’t follow the story: it just became a series of events. Although the final showdown is impressive and memorable, the villain was so forgettable that I did exactly that.

And although the animation has the Bluth soul, it looks visually dull next to his other films. Secret of NIMH sparkled and twinkled, as if the cel sheets were studded with jewels. The Land Before Time was imbued with the hot, ferocious glow of the old world. Tail is just plain colorless. Dark seas. Sewers. City streets blanketed in smog. Average out all the pixels in the film and you’d get a muddy green-gray.

But it’s heartfelt, for all that. And again, the final showdown is both exciting and clever in how it pays off IOUs incurred at the start of the movie.

Roger Ebert criticized the film for being about anti-Semitism while not explaining this in a way that children can understanding.

One of the central curiosities of “An American Tail” is that it tells a specifically Jewish experience but does not attempt to inform its young viewers that the characters are Jewish or that the house burning was anti-Semitic. I suppose that would be a downer for the little tykes in the theater, but what do they think while watching the present version? That houses are likely to be burned down at random?

I understand his point, but children can hear music without understanding the words. Bigotry’s not a complicated concept, and you don’t have to be up to speed on the cultural milieau of 1880s Russia to have encountered smaller versions of it, like playground bullies who pick on you because you look different or talk weird.

We’re not meant to sense any difference between the cossacks and cats: they attack at the same time, like they’re part of the same collective evil. Additionally, the Mousekewitzes are clearly different from the others in a way that transcends species. One of Fievel’s problems in America is that everyone think his name sounds silly, so he changes it to a more goyische Phil. This is matched by a shot of a human Jew likewise changing his name. It’s pretty well done and I had no problems understanding it.

In short, a messy but compelling picture. It’s not true that Don Bluth could do no wrong, but he was doing very little of it the 80s.

Disney’s The Great Mouse Detective came out the same year, with nearly the same concept (a society of mice running parallel to ours). An American Tail is a worthy example of an animated twin film, along with Aladdin and The Princess and the Cobbler in 1992-3, Antz and A Bug’s Life in 1998, The Road to El Dorado and The Emperor’s New Groove in 2000, Treasure Planet and Sinbad: Legend of the Seven Seas in 2002/3, etc. How to explain this? Animated films typically take years to make, which prohibits quick imitations and knockoffs.

(I got Mandela effect’d. I distinctly remember that Fievel sees whales when on the ship. On the rewatch I conducted for this review: nope, no whales. His father describes “fish as big as this boat”, and we hear mournful whalesong, and a later Don Bluth film – The Pebble and the Penguin – features whales, so maybe my brain made mistaken connections. Another example of how movies in memories are not real movies.)

“If we dig precious things from the land, we will invite disaster.”

If you undercrank stock footage of a city it looks frantic, and if you put peaceful music over a natural landscape it looks calm. That’s Koyaanisqatsi: an emotionally moving but intellectually casuistic tale of a supposed clash between modern man and nature.

Director Godfrey Reggio seeks to show the world we live in, but he relies heavily, too heavily, on audiovisual effect, and the film ends up feeling artificial and manipulated, a staged ballet pretending to be honest documentation.

I’m reminded of Luis Buñuel’s 1933 “documentary” of Spain’s remote Las Hurdes mountains, Land Without Bread. The film’s theme – Las Hurdes is a harsh land, where life is cheap – is sold by a powerful shot of a goat climbing a steep cliff and slipping and tumbling to its death. When you learn that the scene was staged (the goat was shot with a rifle) you feel a little cheated.

Godfrey Reggio’s film isn’t deceptive in the same way, but why contrast bustling cities with the Grand Canyon? Is this a logical or obvious comparison? Why not compare a city with a raging ocean? The Antarctic Circumpolar Current carries a million times as many tonnes of water through the Drake Passage as Times Square does cars. There is peacefulness in civilization, and instability in nature.

“Koyaanisqatsi” is a Hopi word, defined (according to Wikipedia) as “life of moral corruption and turmoil” or “life out of balance”. The film ends with Hopi prophecies portending our doom. The film’s reverence toward primitive man is of a piece with most environmentalist scare programming on TV: white people are bad, capitalism is bad, technology and industry are bad. Instead, we should take a moment to learn from beautiful primitive people, who have so much to teach us. It’s funny that most of the people promulgating this regressive message are politically left wing. Nostalgia for the 1950s makes you a conservative dinosaur, but nostalgia for 10000 BC makes you an enlightened child of the earth-spirit.

I don’t argue that modern society is perfect, but our greedy hyper-capitalist “life out of balance” has brought us good things, too: medicine, global communications, global transport, and the ability to make a film such as Koyaanisqatsi. We have created problems (such as climate change), but we can also create solutions. By contrast, the primitive people deified in the film are largely helpless against desertification, disease, ecological collapse, and so on. Any glamor the pre-technological life possesses probably lasts until your first toothache.

While I dislike Koyaanisqatsi‘s theme, I like almost everything else about it. It’s an extremely clever folding of sound over image (and vice versa), demonstrating how one can enhance and illuminate the other.

The visuals are powerful. Clouds slide in reflection across glass skyscrapers, time-lapsed so that they ripple and pulsate like gaseous alien creatures. Streams of traffic flow along streets, accelerated into rivers of pure light. Koyaanisqatsi was a microbudget production and contains a lot of stock footage, but the way this footage is cut together is clever and interesting.

Popular culture was influenced by Reggio’s style. The “sped-up urban footage” motif endemic to 90s music videos started here, for example. Near the end of the movie there’s an extended sequence where the camera tracks a person in the street…until they look up, notice they’re being filmed, and we cut to another person. To be honest, I’m not sure what the point is, but it’s a striking trick, and I’ve seen it imitated since.

Philip Glass’s music is the equivalent of a pointillistic painting, thousands of self-referential cycles of dying notes that seem to melt inside the ear like icicles. The soundtrack is complex yet paradoxically simple. Brian Eno’s pioneering ambient music in the 1970s attempted to reward any level of listener attention (whether you’re focusing intently or listening with half an ear, the music should be enjoyable), and Glass’s work achieves this with even more beauty and concision.

The film was released and the world kept turning. Reggio tried to reignite the fire of Koyaanisqatsi twice, with 1988’s Powaqqatsi (which was about third world exploitation), and Naqoyqatsi (which was about futurism and accelerationism).

The later films had bigger budgets but smaller impacts: they were like bombs landing on a target already blown to rubble. The trouble with making sequels to an experimental film is that, by definition, you’re no longer experimenting: you’re adding to a tradition. And even though Naqoyqatsi (in particular) tried to differentiate itself by amping up the digital editing to ridiculous and obnoxious levels, the Koyaanisqatsi approach had soaked into popular culture, and no longer seemed new or interesting. Hard to be impressed by time-lapse footage when you see the same stuff in Nike ads and Madonna music videos.

Koyaanisqatsi is an awkward beast. Its strongest element is its craft…the craft that subtly works against it at every turn, because it adds distance between the viewer and the reality on the screen. This is one of those films that might be better if it was less competently made, because then we might the truth, instead of a farrago of editing tricks.

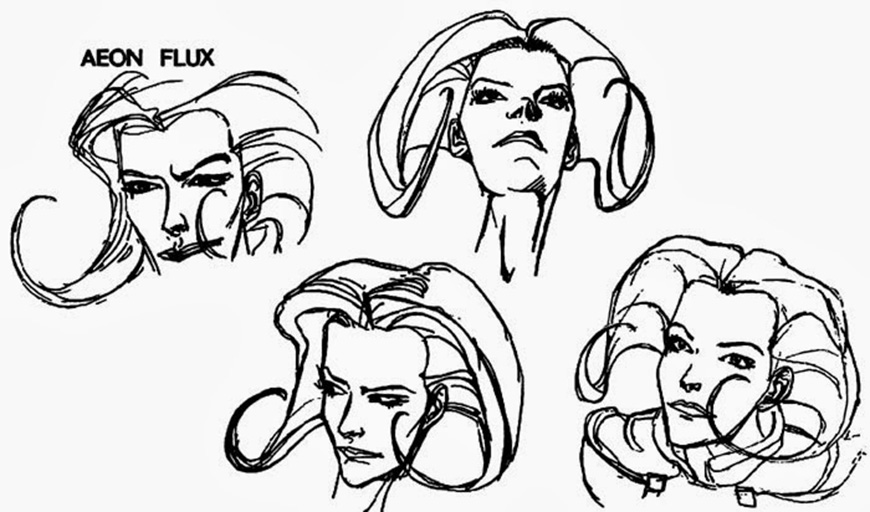

“My name is Aeon Flux. I’m here on a mission to assassinate Trevor Goodchild.”

Fans of “unusual” animated cartoons are often recommended Aeon Flux, which might be like recommending that a fan of chili peppers shove a flamethrower into his mouth. The show is dynamite in your brain, confusing, provocative, unclear, and ultimately highly rewarding.

Even Aeon Flux seems ill at ease with what it is. The first two seasons (1991-1992) are silent 2-5 minute works of expressionism, depicting a woman dying over and over. The third (1995) is a thirty-minute show where the characters “talk” (often without saying much).

It owes debts to German expressionism, Ralph Bakshi, and highbrow anime like Suehiro Maruo. It’s exaggerated to a degree that makes it difficult to successfully parody. In 2005, the fan Livejournal Monican Spies posted a “leaked” Aeon Flux movie script from SomethingAwful, causing confusion about whether it was real or not.

It’s a work of violence and tension: like a screw overtightened until it starts to strip its threads. All the men and women seem on the verge of either murdering or fucking each other. There are fetishistic fixations on body parts (feet, teeth, tongues, ears), and even the violence is a superstimulated joke, with heroes gunning down armies of enemies like a video game with the infinite ammo cheat enabled. The art is Slender Man-disturbing: everyone’s limbs seem stretched out twice as long as they need to be, and sexual acts are distressing, like watching the autophagous mating of two praying mantises.

Aeon Flux‘s mood is that of frustrating uncertainty. You feel like you’re just on the verge of understanding it, if only you knew one more fact. All of this probably makes Aeon Flux sound pretentious and obtuse, but it isn’t.

It’s one of the few TV shows that makes sense.

Small Plot of Land

“For truly barren is profane education, which is always in labor but never gives birth. For what fruit worthy of such pangs does philosophy show for being so long in labor?” – Gregory of Nyssa

Aeon Flux is the vision of a particular man, Peter Chung, who conceived it (partially) as a reaction against unhealthy trends in mainstream TV.

Basically, Chung believes that most TV shows (and many other things besides) are dead. Not in the sense that they’re badly written, unimaginative, or the soulless products of corporations (as if those are barriers to art); rather, he thinks they have a very specific cancer in their core.

The cancer is story.

Consider a basic question: what’s a story? A linear series of fictional events? No, that’s what a story looks like. What a story is (or should be) is a bridge: a way for an artist to connect to you and share his ideas.

This distinction is important. Yes, Catcher in the Rye has a story (Holden Caulfield flunks out of school, fights with a friend, and so on), but this is supposed to encode particular themes: adolescence, a search for authenticity, and so on. That’s the only reason the story exists. The plot is arbitrary: Holden Caulfield could be an Pueblo Indian boy living in 1700. The theme is the important part, not the specific details.

Or consider Hamlet. He is a Danish prince. But are either of those details (Denmark, and royalty) that important to Hamlet? No. You could tell the same story about almost anyone, in any setting.

An overemphasis on narrative is deadly, smothering artistry instead of nurturing it. I enjoy a well-told story as much as the next person (I assume Chung does too), but you can’t care too much about them, or think that they exist just for their own sake. A good story contains the shadow of the author; a bad story – even if it’s well-written – is a meaningless pile of details.

This, in Chung’s opinion, is the reason so many TV shows feel boring and inert. They have literally nothing inside them except story. They’re bridges built to nowhere. They’re a firehose of narrative and narrative and still more narrative, characters doing things and then more things and then still more things until the network cancels the show. As time passes, the fictional universe becomes more convoluted, but no more meaningful. It’s a dying star, expanding and sucking mass until it collapses under its own weight.

Our culture is littered with dead stars: endlessly-detailed fictional worlds that say absolutely nothing. As of 24/12/20, the Marvel wiki hosts 261,582 tedious pages, documenting Steve Ditko arcs from 1965 and timeless characters such as Deathcry [“With the invasion of Earth’s dimension by the entity called the Chaos King, Deathcry (along with other deceased Avengers Captain Marvel, Doctor Druid, the Vision, Yellowjacket, and the original Swordsman), returned from the dead. When Mar-Vell was killed again by the Grim Reaper, Deathcry inherited his cosmic awareness and became an enhanced version of herself as Lifecry.”] What’s the point? Was there ever a point? It’s all trees and no forest.

“I’ve started a few shows out of curiosity […] I get about 4 or 5 episodes in, and there’s always this maddening awareness that: 1. the plot is being dragged out as long as possible, and 2. the storytellers are only using the imaginative, speculative premise as some exotic backdrop to what amounts to soap opera. The provocative implications of the story’s premise are starved. Of course, they’re giving audiences what they want, because the truth is that most viewers aren’t looking to have their thoughts provoked or their minds expanded.” – Peter Chung, 2015, ILXOR

The disease doesn’t create itself, and this thundering pointlessness is what the public wants. The average person consumes fiction on a shallow level, doesn’t enjoy thematic analysis, and the details are all they see and care about. They watch Twin Peaks and ask “who killed Laura Palmer?” They watch Inception and ask “does the spinning top fall at the end?” They’re obsessed with assembling the narrative details of a story like it’s a puzzle to be solved. They hate ambiguity, hate unresolved issues, and hate not being told things. They want the plot to contain certain fixed details (if it’s a Young Adult book, it had better star a plucky, likable protagonist.) And most bewilderingly, they think that excessive narrative detail is in and of itself valuable.

I still remember being assured by a CRPG fan that The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim is an amazing work of art because it has over 1100 unique characters, or something. I haven’t played that game, but who gives a shit? Those characters are all arbitrary and made up. They have no external existence. A Markov chain could have generated them. Even people who should know better fall into this trap. “Tolkien invented his own language!” Is that the important thing about Lord of the Rings? That it’s a Berlitz language course? What’s the story really about?

Aeon Flux is a catharsis from the tyranny of narrative. It dials back the story to barely perceptible levels, and asks you to look behind it.

It’s a work of dystopian science fiction work that takes place in the year [doesn’t matter], featuring an athletic infiltrix whose name is the same as the show’s. She is an agent from the anarchist nation of Monica, and must infiltrate the totalitarian Bregna (for reasons that are unclear and subject to change), which is under the command of the Doctor Trevor Goodchilde.

Someone probably runs an Aeon Flux wiki that charts events blow-by-blow or whatever. Don’t bother reading it: that is the wrong way to analyse Aeon Flux. The sparse, contradictory plot details (such as a heroine you know nothing about, and who ends up dead a dozen times) exist just to collapse on the screen, allowing themes content to emerge. Aeon Flux is like one of those fish that has very thin skin, so you can see the glistening bones and organs inside.

The Inside View

“A concept is a brick. It can be used to build a courthouse of reason. Or it can be thrown through the window.” – Gilles Geleuze

Aeon Flux, fundamentally, is not hard to understand. Its ideas are unusually explicit and clear.

It’s about symbiosis: all ideas actually exist as part of an interconnected system: even the ones that seem to negate each other. Put more simply: the front wheel of a car needs a back wheel, and you need your enemy.

Aeon Flux represents extreme liberty, and Trevor extreme order. They’re ostensibly in conflict, but it’s an act. They’re as reliant on each other as men in a three-legged race.

Without rebels like Aeon, Trevor would have no way to justify his totalitarian measures. She’s the bogeyman, the Big Bad, the Eternal Jew, the Eastasia-with-whom-we-have-always-been-at-war, the Osama bin Laden that means you’re not allowed to bring scissors on a plane twenty years later. People like her are the fuel that keeps the engines of oppression running.

And he feels for himself the allure of freedom (even as he intellectually dismisses and publically denounces it). He’s a hypocrite. He supports global surveillance…but not for himself. He has a private area where he can be alone and unwatched. And of course, his totalitarianism is a manifestation of his own will. It’s very well for him to decide others can’t have rights. If that decision was made for him, would he happily accept it? Or would he rebel, and become like Aeon? He loves power, and does what he must in order to keep it. He has no true allegiance to any ideology, and the exact shape of the world is of no concern to him: the important part is that he’s the one doing the shaping.

Likewise, Aeon is meaningless without Trevor. Her identity is Trevor-I-am-not, and like many rebels seeking to tear down the system, she has no plans for how to replace it. There’s a romance to fighting the evil; there’s no romance to being the evil. Johnny Rotten might raise a middle finger to society, but he’d never want to run society: he’d fuck it all up, and fail, and be remembered by history as a failure, and someone else would be a cool punk rocker. And there are good things in Trevor’s totalitarian state. It’s interesting how it’s always anarchist Monica invading totalitarian Bregna. Almost as if, despite its oppressiveness, Bregna is the one that has built something valuable…

And like him, she’s insincere. She repeatedly has Trevor at her mercy but doesn’t kill him. Without Trevor the game ends. She’d become like those Twitter leftists who has ejected anyone politically different from their social circle and spends their days fighting with other Twitter leftists about whether “latinx” is a colonialist slur, or whatever. Her identity is in the fight, she doesn’t know how to do anything else. She’s a human delete key: eradicating meaning without putting a single word of it back in, and she abhors the blank page an anarchy represents.

They’re both attracted to the ideals of the other, and this sublimates (if that’s the word) as physical lust. They hate that they love each other, can’t escape the umbilical cord. Figure needs ground and yin needs yang.

Another point the show repeatedly makes: nobody is the main character.

Humans have the misfortune of being born with movie cameras in our head (literally: an Arriflex lens is designed to mimic the way our eyes perceive light). We live in a visual world that puts us at the center: if life is a movie, nobody thinks they’re an extra, or part of the second unit. Aeon Flux sometimes toys with the idea. What if you ultimately weren’t important?

The show repeatedly establishes Aeon Flux as a Campbellian hero…and undercuts it in a cruel, laughing way. Usually by killing her, suddenly and for a stupid reason.

In the first episode, she seems the verge of accomplishing her goal…and then dies because she stepped on a tack. The Monican intelligence agency obliterates all evidence of her body, and she isn’t mourned or remembered. Actually, that’s not quite right: in the final shot we see a guy in a store, perusing a sleazy foot fetish magazine depicting Aeon. That’s her legacy. Porn.

This iconoclasm of personal heroism is seen even more starkly in “War”, which runs for five minutes and contains fodder for a dozen doctoral theses. It depicts a battle between Breen and Monican forces under an oppressive red sun. Aeon is leading the charge. She’s a one-woman army, massacring scores of enemies with ludicrous ease. She never misses, and her guns never run out of ammunition. If you saw a Quake player doing what she does, you’d call her an aimhacker, you’d try to have her banned from the server. This feels like a parody of action movies: Aeon’s the hero, invincible, cloaked in Plot Armor.

And then it falls apart. Aeon’s is overpowered and disarmed by a single Breen soldier. He has her pinned on the ground, between gunsights, preparing to shoot. But then her gaze flickers over his shoulder. A friendly Monican agent is sneaking up behind him! Hurrah!

…but the Breen soldier shoots her, and then effortlessly kills her would-be rescuer, too. After this jarring anticlimax, the episode continues on in a bizarre direction. The camera changes sides, and we follow the nameless Breen soldier through the battle. He does the same thing Aeon did: except he’s slaughtering dozens of Monican soldiers. The exact same heroic beats and notes are used, the same filmmaking tricks that Peter Chung used to valorize Aeon are now to valorize a nameless Breen grunt (example: how he’s shot from an downwards angle, silhouetted dramatically against sky like a monolith)…it doesn’t seem to matter that he’s fighting on the wrong side.

We’re struck by the sense that the Breen soldier is undoing all of Aeon’s progress. And that he’s no less of a hero than she was. This is pointed commentary: it’s not just your side that gets to have heroes. There are heroes who hate everything you stand for, heroes who want to napalm your children.

But it goes on. The seemingly invincible Breen soldier meets his end: a Monican agent kills him. The camera changes allegiances again: following the Monikan agent, who slaughters endless numbers of et cetera (this time the parody is hilariously thick – the guy using a medieval sword, and the Breen soldiers can’t defeat him even though they have guns. It’s not even trying to be believable), until he meets a Breen woman, who…

The “War” episode ends with a characteristically picture-containing-a-thousand-dreams shot: the camera focuses on a punctured pipe, which is slowly leaking oil into a tiny puddle on the ground. Do we learn the fate of the final set of characters? Do we even find out who won the battle? Nope. Fuck you. Here’s a puddle on the ground. The camera has no friend. It recognizes no main character. The Universe doesn’t have an “eye” – and if it did, you’d be of no particular interest to it. It would be as likely to stare at a worm than it would be to follow your adventures.

…These were examples of what you get from Aeon Flux. I’m not claiming they’re profound themes, or original to Aeon Flux, or even that Aeon Flux always presents them in a skillful way. Sometimes things get a bit too drippy for my preference. In episode one, we get shots of crying women and children standing over the bodies of the soldiers Aeon killed (geddit? They had lives too!) which feels manipulative and unsubtle – although the shot of hapless Breen janitors staring at an ocean of blood with mops in their hand was funny.

Nevertheless, they’re themes. Ideas. Amid a sea of monster-of-the-week or verbal diarrhea, Aeon Flux is actually saying something. The glass teat learned to speak.

The Hot Equations

“Television knows no night. It is perpetual day. TV embodies our fear of the dark, of night, of the other side of things.” – Jean Baudrillard

Chung got the show made by lying.

“Initially they had a hard time understanding what Æon Flux was and what I was trying to do and why it belonged on Liquid Television. So I kind of had to pitch Æon Flux as a parody of action shows or action movies because everything on LiquidTV was a parody of something.” – Peter Chung, FormerPeople, 2014

Aeon Flux, aside from a few moments, is not a satire of anything. But this is how an auteur survives in Hollywood – you tell the suits what they want to hear, cash your checks, and then make whatever you were going to make anyway. Chung lucked out. Aeon Flux tested well, and MTV decided to keep rolling the dice with him.

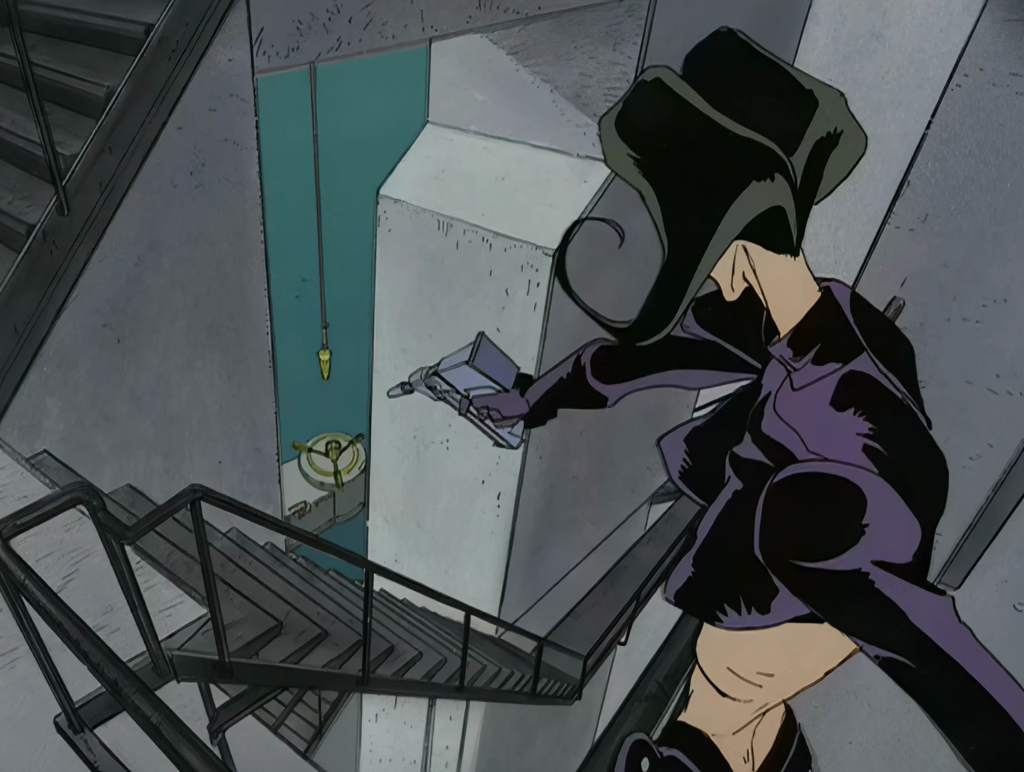

He’s clearly a virtuoso: and his talent is immediately visible on the screen. It’s not a slow-burn type of show, it instantly grabs you with its visuals and sound design. The colors chosen, the way the action flows, the music, Aeon Flux is craftsmanship at a very high level.

And it encapsulates what I like about hand-drawn animation, the tension of imagination and constraint. In theory, you can draw anything you like, but it’s expensive and slow. TV runs at 24 frames per second, so an animator will potentially need twenty four unique pieces of art for every single second of run time. Most animation cheats by stretching one picture across multiple frames – it’s common to hear about animating “on the twos” (every 2nd frame has a new picture, like Disney movie), or “on the threes” (every 3rd frame has a new drawing, which is mostly reserved for anime and low-budget programming).

Despite these cost-saving measures, a lot of art has to be produced, even for a five minute work. You can’t not know what you’re doing. Every second of animation is blood squeezed from stone.

This puts the director on the ropes, forcing him to make sacrifices and tough decisions about what’s important to the vision. The sky is limitless, but your rocket ship only has a small amount of fuel. Where will you go?

This is why works of animation tend to be tightly scripted and edited: the action nailed in place by keyframes as precise as rivets on a battleship. This doesn’t mean they’re good, but at least you avoid the sort of aimless gonzo “just film whatever” bloat common to live action TV. Aeon Flux gleams with craftsmanship, but it’s all precisely directed and focused.

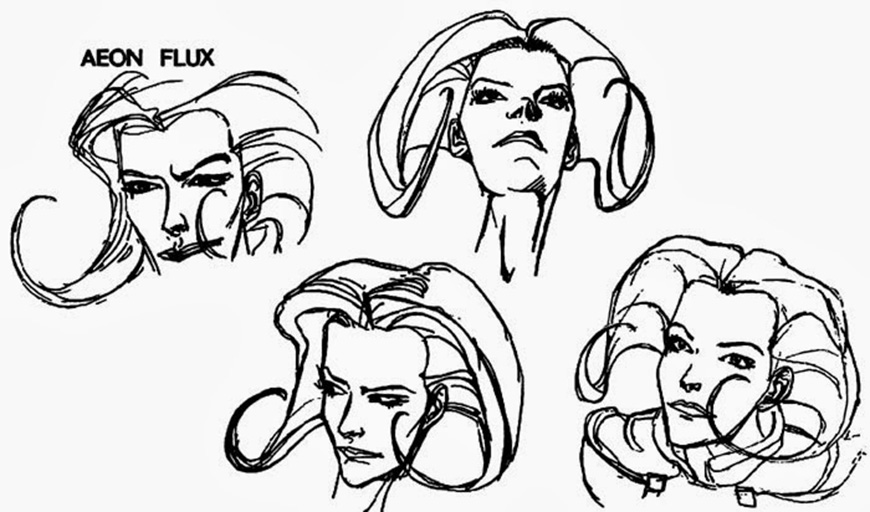

Which isn’t to say that Chung doesn’t splash out effort wherever he can. Sometimes he deliberately take the hard road. For instant, hand-drawing every single eyelash on a face. I’d never seen that on a TV show before. Aeon Flux has a visual style that’s entirely it’s own.

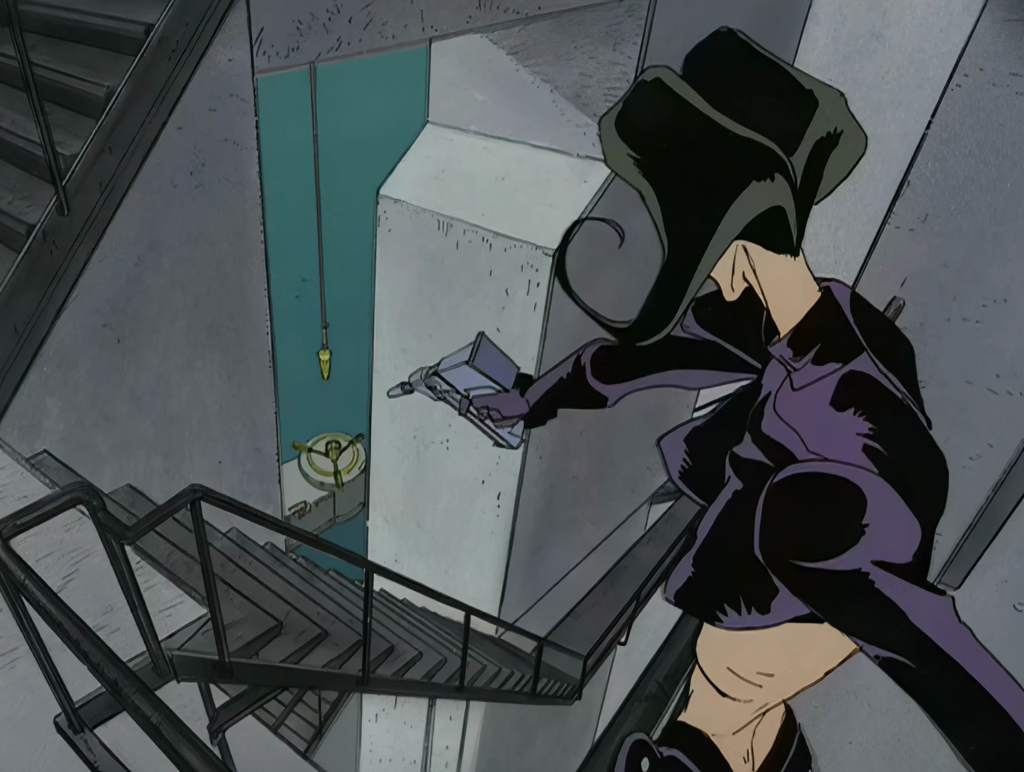

And although Chung attended Cal-Arts, members his team didn’t always have the “usual” animation CV. Background artist Tom McClure, for example, trained as an architect, and seems to draw on this to create baroque environments that are nonetheless sensible and physics based. You can feel his otherworldly structures creak and thrum as they disperse force from the wind. Even the pilot episode (which McClure didn’t work on) features astounding detail. It’s typical for animation to blow its wad on the focal foreground elements (characters, and so forth), with backgrounds becoming a barely-present outline. But in the first episode we see Aeon Flux is breaking into an industrial complex of some kind, and although it’s clearly complicated, you can sense everything architecturally connect and make sense. Aeon Flux’s world is an arbitrary and confusing and self-contradictory one, but it’s also as perfect as an ice crystal.

The sound design is another strong point. Drew Neumann’s music is particularly felt in seasons 1 and 2, almost substituting for the missing dialog. It’s full of stabs and swirls and Orchestral motifs – arty and baroque stuff that matches, twists, and subverts the action like a riptide around the ankle of a swimmer. The Aeon Flux theme is essentially the Indiana Jones theme moved to Phrygian and 7/4 time. It sounds almost heroic but warped, like the melody has been worked over with a flamethrower and melted out of shape.

Even the names of the characters are chosen with care, and advance particular themes. The show’s an Freudian paradise.

Bregna sounds like regnant, but the addition of the letter B makes it an ugly word: slimy and unpleasant in connotation. It sounds like pregnant, smegma, phlegma, magma. It also sounds like impregnable, which would be ironic, because it isn’t. Set in opposite is the rogue state of Monica. Hegemonic? A broken part of a whole? It’s possible. I think it’s more likely a derivation from the Gnostic concept of the monad (monas), the highest level of God.

Aeon, in Gnosticism, is an emanation of God, a specific particle of the Monad. Flux indicates change, shift, perhaps corruption. These holy emanations come in male and female pairs called a syzygy: it seems that Aeon Flux and Peter might be such a union.

And consider Peter Goodchilde’s own surname. It’s ghoulishly nice. Isn’t there the whiff of something ironic and sinister in good child? It’s the sort of thing a defensive mother would say. Please officer, my son would never do a thing like that. He’s a good boy.

Tomorrow

“The rulers wanted to deceive man, since they saw that he had a kinship with those that are truly good. They took the name of those that are good and gave it to those that are not good, so that through the names they might deceive him and bind them.” – Gospel of Philip

Aeon Flux was a classic case of “nobody heard the song, but those who did started a band on the same day”.

It punched above its weight, influencing a lot of things and a lot of people. You might not have seen Aeon Flux, but you’ve probably seen something from Aeon Flux: its visual style is aped in the Matrix and Blade movies, and in the aggressive, anatomy-defying fetishism of Rob Liefeld’s 90s comics. In May 2020, Elon Musk made the questionable decision to name his newborn son after the character.

It anticipates Tomb Raider and Resident Evil. One of barriers Chung faced from studios and audiences is that nobody had seen a heroine like Aeon Flux before. Now, everyone’s seen a heroine like Aeon Flux before – the most striking imitator being (again) the Matrix. Trinity is a cold Aeon Flux, hiding her fly-trapping eyelashes behind wraparound shades.

It inspired comic books and manga. It was made into a movie starring Charlize Theron, which I haven’t watched.

More than anything, it anticipated videogames that wouldn’t be made for another 5 years. This is the big mystery to me. I can’t find anyone from id Software or Valve claiming that they were inspired by Aeon Flux. Yet the action scenes are Wolfenstein 3D before Wolfenstein 3D, and the stealth parts suggest Thief and Half Life. The indoor environments just scream “mid-90s shooter”, polygons slotting together with Jengalike perfection, illuminated by raytraced lightmaps.

The only thing Aeon Flux has yet to inspire is a continuation of itself.

From time to time, I hear rumblings of an Aeon Flux revival. It’s debatable whether this will happen, or whether it needs to happen, or whether Chung will be involved.

Chung’s own mindset has moved on past Aeon Flux. It’s a concept he created in 1991, and it has some undeniably juvenile aspects – Aeon Flux’s sleazy T&A bondage outfit doesn’t seem connected with anything the show’s trying to say, other than to give it a salacious hook. As revealed in 2005, Chung had originally intended Aeon Flux to die – her first death was to be her final death – but as the show continued, he realized she had to come back.

Aeon Flux represents his vision, but only in a confined and compromised form, made to appease censors and bean-counters. If he’d had perfect freedom, it might have been very different. There’s nothing wrong with that. Everything on TV exists under those conditions. But nor is the show a work of holy scripture, or a sublime work of pure auteurism.

Here’s an interview where the interviewer asks him about a certain quote…but Chung no longer remembers it. It’s been too many years, too much water under the bridge. He now speaks about Aeon Flux with the measured care of a man talking in a second language.

“Trying to redo Aeon Flux now, over ten years since the last time I worked on it, I realized that my own interests are very different. My own take on the character is very different from what it was originally. I almost get the feeling that trying to adapt the character to the ideas and themes that interest me now would require reinventing the character altogether and at that point why do Aeon Flux? Why not just create something else? So that’s really the direction I want to go in.

One of the things that I’m working on now is an adaptation of Cyborg 009, which is a Japanese comic book character and an animation series from the ’60s, which I grew up with. Japanese animation is very popular all over the world, so a lot of it is being adapted into animated features.” – Peter Chung, 2008, AWN

Chung still clearly likes Aeon Flux, still enjoys talking about it and thinking about it. But it’s no longer his, exactly. He’s moved on.

A successful continuation of Aeon Flux would have to continue the show’s spirit, not its literal events. It might not even necessarily contain Aeon Flux and Peter Goodchilde. That risks turning the show into a formula and a franchise: Aeon cavorting around in leather bondage gear, shooting some people, someone mumbles some confusing Gnosticism, tune in next week. And that’s another variant of the trap Chung tried to avoid. It’s not necessary for things to run on for ever. Sometimes finishing points are necessary. A straight line, if followed forever, will inevitably lead straight over a cliff or into the sea.

What happens next? What needs to happen next? Nothing, really. The past is set, and Aeon Flux still stands: a numinous monument to contradictions, flaws, internal collapse, spirituality, mundanity, and change.

Judged on its own, it reaches great heights. Compared with the rest of TV (both in its day and ours), it splits the heavens. The world is full of literary smokestacks, jetting thick black clouds of pure narrative, clouds that are endlessly complex in their hills and valleys and yet are still a black petrocarbon mass that chokes anyone who breathes it. Aeon Flux is a reminder that behind the smog there lies the sky. It is cold, it is strange, it is huger than huge, and if you have the will you can spread your wings and fall endlessly into it.