1986’s Darkness Descends was one of the most extreme metal albums of its age. I don’t mean the 80s. I mean the age of recorded music. Even in 2021 it’s a shock and affront, a pile of little limbs, a terrifying journey that no combination of programmed drums and Protooled guitar tracks can replicate. Darkness Descends is the Tsar Bomba of metal: decades old, technologically obsolete, but still (in some ways) unsurpassed. It’s less an album than a signpost: mankind went this far into hell and no further.

It’s a good example of pre-death metal (dying metal?). Although it’s still thrash – the vocals are barked but not growled, the guitars are just a semitone down, and the drums lack the intimate, in-the-room quality of early death metal – you can still see that by 1986 we were ready to leave thrash behind.

The riffs are a speed-picked blur, the sound of a guitar sawing through metal. The drumming is intense and technical. And although the seven tracks are still songs, they’re also less than songs. They barely hold together, and constantly seem on the verge of exploding like tempered glass. Dark Angel weren’t the first to point in that direction and they never played death metal themselves (their career ended on a different milestone, the tech-thrash Time Does Not Heal), but once you get here, Scream Bloody Gore, Morbid Angel and Cannibal Corpse become inevitable.

There’s also a surprising Metallica influence. “Black Prophecies” is the band’s attempt at a Master of Puppets style epic, and there’s Hetfieldian touches throughout – like how the title track has that descending-power-chord-over-choppy-riff trick straight out of “Disposable Heroes”. Jim Durkin was a big NWOBHM fan, and “Merciless Death” opens with a tribute to Iron Maiden’s Steve Harris.

Slayer is an even more immediate touchstone. Although Darkness Descends edges out Reign in Blood in quality and heaviness, Gene Hoglan would often mourn the fact that the label couldn’t get Darkness Descends out sooner than November 1986, by which time they were derided as “Slayer babies”.

Like Reign in Blood, Darkness Descends is very, very, very fast. The most excessive tracks are “Darkness Descends”, “The Burning of Sodom”, and “Perish in Flames” which are around 250 beats per minute. Unbelievably, these songs were actually performed faster live. Drummer Gene Hoglan was famous for slamming No-Doz before a show and just beating his kit into scrap metal. It’s a miracle he still has a heartbeat, and maybe he doesn’t.

Fast metal is boring, and these songs are Darkness Descend’s least exciting moments. The snare registers as a weightless popping sound. The guitars lose any semblance of musical notes and become an angle-grinder. Don Doty’s vocals are just a rapid-fire “jabba-jabba-jabba” like an TV informercial salesman rushing through all the terms and conditions. I don’t always skip these songs, but I don’t feel too bad when I do.

When the album slows down, it wrecks all in its path. “Black Prophecies” is among the greatest metal songs ever recorded. If it had any more atmosphere, it’d be the surface of Venus. Tom rolls detonate like thunder. Sections develop in a dark, nauseating churn, each seeming to collapse into the next, while riffs bite like the endless teeth in a shark’s mouth. It’s an incredible song that I appreciate more each time I hear it.

It’s a lesson in how to do much with little. When I play the song back in my head, I hear all things that aren’t there: tolling bells, marching armies, and nagging violin ostinatos. But actually, the “bells” are Rob Yahn plucking high notes on his bass, the “marching armies” are Gene Hoglan playing a sycopated snare rhythm, the “violins” are Durkin and Meyer picking notes close to the bridge. These guys take generic thrash ensemble and bring a whole orchestra to life, which is amazing.

The lyrics in general are interesting, catching Dark Angel at a transitional point. Their first album We Have Arrived tended towards the”we’re a thrash band and we’ll kill you all! BEER! PIZZA! PARTY!!!” school of lyricism. Exodus, while later albums read like an aberrant psychology journal. Here, the lyrics are dark and fantastical, suggesting a world of myth and shadow.

The man singing them proves a mixed bag. Don Doty’s goblin-like barks sound diabolic and menacing, but often he lapses into a kind of talky whisper that’s pushed a bit high in the mix. Part of the problem might be the extreme speed of the songs. Another might be the fact that all the lyrics were written by the band’s drummer – Doty often seems to be struggling to enunciate troublesome syllable clusters that just aren’t natural or easy to sing (“thecityisguilty! the crimeislife! thesentenceisdeath! DARKNESSDESCENDS!!!”) It’s not for no reason that singers usually write their own lyrics, although maybe that’s another way Dark Angel anticipated death metal. It doesn’t matter who writes the lyrics of the average death metal band – the vocals are so incomprehensible and distorted that it’s impossible to tell what they’re saying. For some modern bands I’m almost sure the lyrics sheet is written after the vocal tracks are laid down.

Darkness Descends is an unusual record, and not only for its brutality. Thrash metal is characterized by formal minimalism, with all sorts of disasters resulting from pretension or overdeveloped ideas (Metallica hits that point for some people.) But Dark Angel’s more elaborate moments are the album highlights, while their attempts at ripping your face off are often a little lacking.

St Anger is Metallica’s 8th studio album. It was released in 2003 through Elektra Records, and is famous for being very bad. Worse than previous Metallica albums. Worse than diarrhea. Worse than papercuts. Worse than getting banned from a chat room just when you’re ready to sling a mortally wounding insult. Worse than long trips in a car that’s making a rattling sound. Worse than when the pastor says “now, let’s go a bit deeper into Paul’s contextual usage of ‘divinity’…” at 11:59am on a Sunday morning. Worse than spiders. Worse than Vegemite. Worse than spiders coated in Vegemite. Worse than Vegemite coated in spiders. Worse than hard drive failures. Worse than finishing your Greek homework and realising you forgot the accents. Worse than merging two columns in a 10,000 line database, and the line count is off by one. Worse than people calling the internet “the interbutts”. Worse than puns that aren’t puns (ie, referring to Fox News as “Faux Noose”). Worse than remakes of movies that came out last year. Worse than an old friend wants to catch up and after half an hour of small-talk he says “have you heard of an exciting new business opportunity?” Worse than a friend who tells an unfunny joke and pauses for you to laugh. Worse than filling up your petrol tank from a diesel pump. Worse than knowing that you can’t go to a Halloween party dressed as Charlie Chaplin because everyone will assume you’re Hitler. Worse than holding the bag. Worse than hodling the bag. Worse than having your mother date your high school bully. Worse than having to close your Satanic pedophile ring underneath a pizzeria because people are getting wise. Worse than Googling a computer problem and discovering you’re the first person it’s ever happened to. Worse than realising you were born to play a sport that nobody enjoys. Worse than having a special interest that brings you into contact with nonces. Worse than spontaneously exploding. Worse than biting off half a sushi roll and the seaweed is all ragged and you know there are ragged parts stuck to your teeth. Worse than calling someone “cringe” and then discovering they run a charity for blind dyslexic orphans. Worse than learning enough 3D modeling to notice fake special effects in movies but not enough to be hireable to work on a movie. Worse than being in a Metallica cover band circa 2003. Worse than the 2005 film Elektra. Worse than the fact we’re now 1/4 through Biden’s first term and 80% of all political news stories are still about Trump. Worst than women who describe themselves as “MILFs” when they’re 21 years old. Worse than typing out a 800+ word rebuttal to something that was autogenerated by an AI. Worse than realising you’ve pronounced “hygge” incorrectly for 4 years. Worse than being a Pitchfork hipster and building a time machine and then using it to kill someone other than Hitler because it’s ironic. Worse than being a hand model and your new roommate is a compulsive battle-axe juggler and shuriken collector. Worse than starting something and not finishi

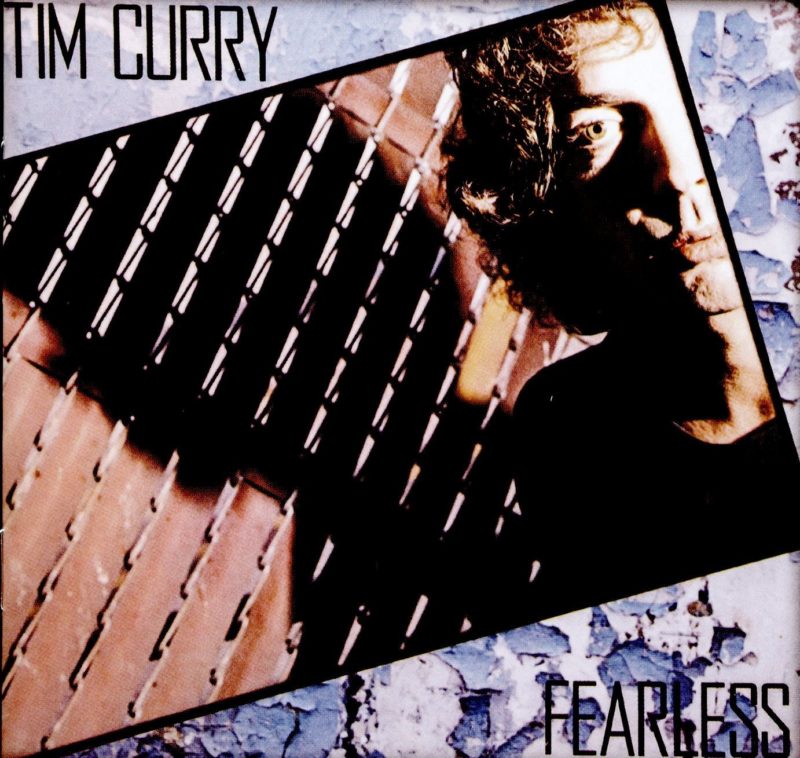

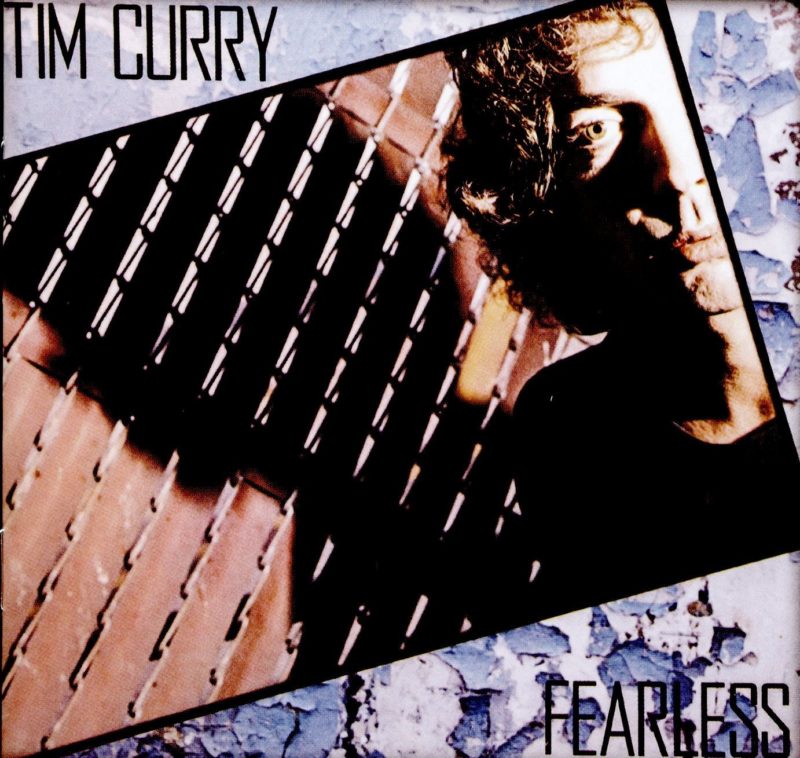

There’s a British TV figure known for his performances of a pirate, a transvestite, a mass of sentient toxic sludge, a roided-up penguin, a horned devil, and an evil clown. But enough about Boris Johnson, let’s talk about Tim Curry.

David Bowie was a musician who dabbled in acting. Curry was the opposite: an actor with aspirations of rock stardom. But where Bowie’s film appearances are (overall) remembered fondly, Curry’s albums are barely remembered at all. His failure to “break out” as a rock frontman in the late 70s evidently galled him, as seen in interviews like this one, where he takes shreds out of a journalist for asking him about Rocky Horror Picture Show (“I think that it is one of the most boring journalistic openings that I have ever heard”). These albums are sad to experience as a Curry fan: listen to them and unfulfilled dreams float past.

Regrettably, the same is not true for good music. 1979’s Fearless has one outstanding moment: “I Do The Rock” lives up to its title, shameless and vulgar and full of panto swagger. You’ve never heard “rawwwhhhkk” pronounced the way Tim Curry pronounces “rawwwhhhkk”. Album closer “Charge It” is less memorable but at least has a pulse. These two songs could have made it onto a good Lou Reed album, unlike the others, which would more or less make weight on a shitty Lou Reed album.

The songwriting is a flat line: boneheaded rockers like “Right on the Money” and “Hide This Face” sound written by hacks-for-hire from the bottom tranche of A&M’s songwriting division (dismayingly, they were written by Curry himself). Robotic performances with no dynamics means Curry has to salvage them with the force of his personality, and although he has charisma and a good voice, he doesn’t understand “singing” that well: often his vocal work devolves into shouted theatrical tirades over repetitive musical motifs. It’s amusing for a few songs, less so for a full album.

“Paradise Garage” is a would-be disco song with a Bee Gees bassline buried beneath a tacky wall of guitars and Curry (apparently) making up lyrics on the spot in the recording booth. It has all the club potential of Little Jimmy Osmond. “Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire” is a cover of Joni Mitchell, a woman who has dubious right to oxygen, let alone covers.

Curry needed better songs, but even if he’d had them, where does a man like him fit in Thatcher’s Britain? The most relevant cultural moment (campy, wig-snatching glam rock) had passed five years earlier – Queen aside, 1979 was year of Blondie, ABBA, and The Police. Soon Bowie and Boy George would almost be issuing public bulletins declaring that they weren’t gay. Fearless is an interesting curio from a straightlaced time, but little more. Not worth getting for one great song.

I almost forgot to tell you about the power ballad “SOS”. I have a suggestion, though. Burn a copy of Fearless, but skip over track 4. Got it? Your new copy should go straight from “I Do The Rock” to “Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire”. Now take the original CD and drive it to an empty field somewhere. A place where no bystanders would be hurt if six megatons of thermobaric ordnance were to strike the ground, if you catch my meaning.

Then, contact the CDC, the FBI, the DHS, the MI6, every alphabet agency your country has. Tell them the CD contains anthrax, national secrets, fascism, child porn, and systemic racism. Yes, all of those things at once. Say that the anthrax spores are arranged in the shape of a naked eight-year-old child-of-color being molested by a government agent who’s sig heiling with one hand and downgrading the child’s future credit score with the other. Then retreat to a safe distance, strap on heavy-duty protective goggles, and watch the world become a better place.