The Argument, Grant Hart’s final solo album, was released in 2013, four years before his death.

Who is Grant Hart? If you know him at all, it’s probably as “the less famous guy from Hüsker Dü”. There are worse obituaries, but if you ask a group of children who they want to be when they grow up, few will say “the less famous guy from Hüsker Dü”. Not many will say “the more famous guy from Hüsker Dü” for that matter, either.

Hart deserved better than he got. Overshadowed both by Bob Mould’s pyroclastic distorted guitar chords and forceful personality, it was easy to see him as a lesser talent. But one day I took stock of my ten favorite Hüsker Dü songs, and about seven of them were written by Hart. From “The Girl Who Lives on Heaven Hill” to “She Floated Away” to his solo albums, he was a genuinely brilliant pop songwriter.

And he was weird. Bob Mould would never and could never have made The Argument.

It’s a 20-song adaptation of Milton’s Paradise Lost, based on a treatment by William S Burroughs. It sounds (and is) cheaply made, consisting of noisy guitars, synth loops, and found sounds apparently recorded around Hart’s house (such as a barking dog). Seldom has such ambition been realised through such humble material. Hart has created a tableaux of the Original Sin out of carpet fluff, dryer lint, and spilled breakfast cereal.

There’s not a trace of hardcore punk to be seen, and little alternative rock. It’s just Grant Hart’s stripped-back and heartfelt (Hartfelt?) songwriting, which always seemed to exist beyond influences. Sometimes the cheapness of the album works against it: “Morningstar”, for instance, features a loud programmed drum loop. It’s distracting, and all I can focus on. But far more often than not an entrancing mood appear. “Awake, Arise” is dire, and builds up like a thundercloud. It’s followed by “If We Have The Will”, a military march of painted toy soldiers written in 9/8 time. “Sin” goes heavy on the blues.

By the time “Letting Me Out”, “Is the Sky the Limit?”, and “So Far From Heaven” roll around, the album is (metaphorically) on fire. None of these songs contain a single dull or uninspired moment. “War in Heaven” is woven from agonizing jagging synths and samples. “Underneath the Apple Tree” is focused around lyrical storytelling – Grant Hart’s devil is far more avuncular and likeable than the Rolling Stones’ or Marilyn Manson’s. The six minute title track is boring and can be skipped. But the album ends on a high note, the energetic and frantic “Run For the Wilderness”.

One of Hart’s goals for the adaptation was to remove explicit references to religion – a blind listener might not even make the Paradise Lost connection. Lyrically, the story jumps around a bit and is kind of out of order. I think he might have taken inspiration from CS Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters – you think you’re reading the demonic missives in chronological sequence, but the celestial method of dating need not overlap with that of mundanity.

But mostly, Hart hasn’t recreated the world of Milton, or Burroughs, or even Moses, but has created a self-referential cosmos that’s entirely his own. Obsessive, detailed, and tuneful: The Argument could be a concept album about its creator’s mind. Grant Hart is gone, but will not be forgotten. Hüsker Dü. Do you recall?

Drop a stone in a pond. Ripples will spread out. Cultural events are similar, but sometimes the ripples occur before the stone falls. Facebook, iPhones, and The Lord of the Rings (books, not movies) are stones. Myspace, Blackberries, and The Hobbit (book, not movies) are ripples. Although important in their own right, they had the misfortune to occur before a similar (but much bigger) thing, and have been swallowed by it within the public mind.

Cassette tapes (and the culture surrounding them) were ripples: the stone would would fall twenty years later. They were ugly plastic rectangles containing about ninety meters of magnetic tape. Music recorded on them usually sounded hissy and noisy (this itself became an aesthetic), but the tapes were so cheap that it was now possible for the average child to copy music. People would tape songs off the radio (complete with hacky DJ voices and commercials), as well as make illegal bootlegs of live bands. This led to a full-blown kulturkampf between tapers and record labels in the 1980s, culminating in the BPI’s often-parodied “Home Taping Is Killing Music” slogan.

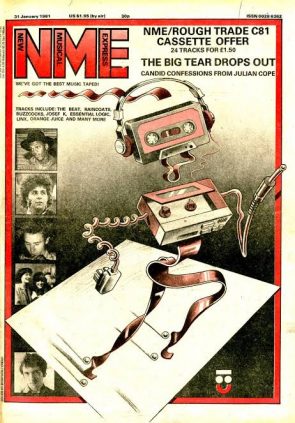

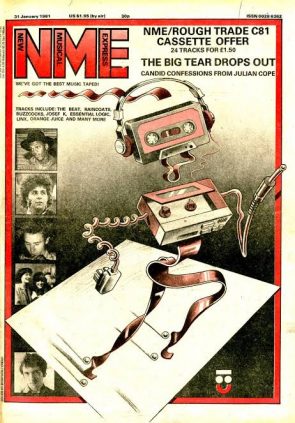

Some labels fought cassette tapes, but others embraced them. C81 (a compilation cassette released by NME at the start of the tape boom) is an example of the latter, containing twenty-four tracks of British and American “indie” music circa 1981. I’m sure that all the bands involved were branded as sellouts until their dying day.

The tracklisting is as schizophrenic and scattered as any fourteen year old’s mixtape: legends like Pere Ubu and Scritti Politti exist alongside bizarre “art” projects like Furious Pig that apparently did nothing notable except appear on C81. It’s both ethnically and musically diverse, with selections of funk, ska, reggae, dub and so on. Also, whoever put this together clearly wanted to fuck Lora Logic, because she’s on here twice.

As with many compilations, it sprays and it prays. “You won’t like everything, but you’ll probably like something.” I enjoyed the apocalyptic mini-epic “The Seven Thousand Names of Wah!”, the histrionic but understated “Shouting Out Loud”, the Scritti Politti song, and “Parallel Lines”, which is a thesis on everything punk should be: taught, fraught, and small.

But the best piece of music C81 has to offer is Cabaret Voltaire’s “Raising the Count”, which initiates the listener into a kind of electronic Satanic ritual: a black mass powered by 200 watts. The song is as destructively repetitive as a pneumatic drill rammed through your basilar membrane. You will either turn it off in confusion, or get sucked into a hypnogogic state. Cabaret Voltaire had existed for most of a decade by the time C81 came out, and would continue to release music for about twelve more years (although I find their later techno/house music to be less interesting than their early experimental work).

So, good music, and good capture of a particular moment in British musical history. C81 is now most easily acquired in digital form, which was the next evolutionary stage of tape culture. Cassette tapes were ripples, and digital piracy was the stone, doing everything cassettes had done (including killing the music business) about two orders of magnitude more successfully. The record industry profiting off tape trading seems gruesomely poetic in retrospect. It’s as though Louis XVI, before the French Revolution, had invested royal money in guillotines.

For over eleven years, Reality wore a title it was never meant to bear: that of Last David Bowie Album.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. Bowie had every intention of continuing recording and touring. But in 2004 (near the end of the grueling 112-date Reality World Tour) he collapsed on stage in Germany, evidently from a heart attack. The beautiful statue that had worn countless layers of paint had suffered an interior crack.

There were no more tours, no more albums. For over ten years, Reality was the end. It never felt like one: it was a small, transitory album, trivial at times, and lacked an identity. It wasn’t a grand, towering tombstone, with HERE LIES DAVID BOWIE etched in stone.

Maybe its battlefield promotion helped it, giving threadbare songs like “She’ll Drive the Big Car” and “Looking for Water” more attention than they deserved. But after The Next Day came out in 2013, Reality fell into its correct place. It’s in the lower half of Bowie’s albums, which is no demerit. It’s also in the lower half of Bowie’s post-70s work, which probably is.

It has good songs, as they all do. “Pablo Picasso” takes the Modern Lovers’ one-chord pony on new and surprising adventures. “The Loneliest Guy” is very unsettling, like a taut and humming spiderweb of Mike Garson’s reverb-soaked piano and Gerry Leonard’s vibrato-drenched guitar. Bowie seems to be drawing from Scott Walker’s approach to songwriting here, turning the soundscape into a huge blank space that crashes sea-shell-like with the sound of its own emptiness.

“Fall Dog Bombs the Moon” is like the last Tin Machine song, very dry and underproduced. The lyrics are both cryptic and heavy-handed, clearly exculpatory of George Bush while not really naming him. I sort of like it.

“Try Some, Buy Some” was originally produced by Phil Spector, and sounds like Regina Spektor. I’ve only listened to it once or twice – a little of this stuff goes a long way.

“Reality” is noisy and quickly becomes unwelcome: it’s like a jam session that nobody has the courage to end. But closing track “Bring Me the Disco King” is another album highlight. It’s another powerful minimalistic song, consisting of Bowie’s voice, Garson’s jazz-influenced piano playing, and Matt Chamberlain’s drum loops. The result is enchanting: it has some of the same magic that “Lady Grinning Soul” had, all those years ago. But then Garson starts vamping all sorts of neo-tonal stuff over the outro (as if trying to recapture “Aladdin Sane”), and a lot of the magic leaves.

And then Reality ends. It was supposed to be yet another stone in a road with no clear end or destination: the road of life. The trouble with such a road is that it can just stop at any moment, without warning, and you have to accept that the final moment has come. For a while, Bowie fans had to accept that this album was his Abbey Road. But eleven years later, a new stone appeared.