Every culture has a beloved national dish that amounts to “take all the leftovers and put it in a pot”. Hours is David Bowie’s version of that, an unfocused collection of tracks from a videogame, an unfinished Reeves Gabrels solo album, plus some other crap, with a production job so lame it ruptured time and space.

Look at the cover. You already know how it sounds. Tepid, breezy, housewife-hooking AOR pop rock with no edge or bite. Bowie tried to get TLC to guest on “Thursday’s Child”. I don’t know what’s sadder: that he seriously had that idea or that it probably would have worked.

“Thursday’s Child” is the first single. It features a lame R&B-inspired backbeat, gratuitous female backing vocals, and greasy, syrupy synths. Someone once said that synths are to American musicians what firewater was to the Native Americans. I agree, and wish they were what smallpox blankets were for the Indians.

“Something in the Air” is six minutes of boredom and glitchy sound effects. I don’t know what Reeves Gabrels is playing on guitar. It doesn’t relate to the music in any way. It’s like they recorded him noodling at soundcheck time and put it on the record. This was Gabrels’ final studio release with Bowie, quitting while he was behind.

“Seven” is an acoustic song with very loud slide guitar parts. Not bad, but anyone could have written it.

“What’s Really Crappening” is Bowie’s infamous “cyber-song”, meaning its recording was broadcast via livestream. There were probably people who racked up a $40 phone bill over their 56ks listening to Bowie make this – they should have watched the video of the dancing baby instead. The lyrics were partially written by a fan, Alex Grant, who won a contest on Bowie’s website. Nobody can find any trace of Grant now. He may have entered the witness protection program.

“Brilliant Adventure” is etc…

You get the idea. I dislike hours greatly, there’s something cold and dead about it that I don’t hear in any of the other “bad” Bowie albums. Even Never Let Me Down and Tin Machine I have odd charm that renders them lovable from a certain perspective, but this has none (and no artistry either). This is a strong contender for the worst thing Bowie ever recorded on a major label.

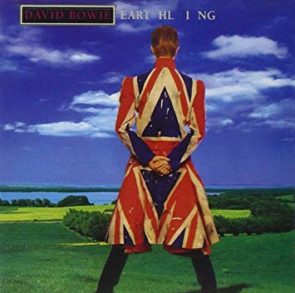

The digital sampler is one of the great musical instruments of its ages, nearly equal to the electric guitar. Or maybe it’s an anti-instrument – rather than creating music, it takes the music of other people, and fascinatingly tortures it to death.

The Akai MPC sampler is to music what the AK-47 is to firearms – a mass-produced weapon that allowed peasants to get into the game. Not knowing a damned thing about music was no longer an obstacle to making it. Illiterate rappers could slice parts out of someone else’s tracks, reconstruct them into Frankensteinian monstrosities, and play the results to a crowded dancefloor. Sampling culture reveled in taking music out of its natural environment, and shoving square pegs into round holes. It put Beethoven’s Fifth over hip hop beats, and uncool dad rock over souped-up breakbeats. Much of the Mona Lisa’s effect comes from the fact that you must pass through an austere gallery before you see it. It would have a different impact if you saw it in a sewer. Sampling works by the same principle: it allows us to hear old music in a new way, breaking preconceptions and forcing the mind into unfamiliar paths.

Bowie’s 1997 album makes a fetish out of sampling. Most of Reeve Gabrels’ guitar riffs are actually recorded samples. Wild scratchy noises spray like jets of graffiti from an aerosol can: these are saxophones, sped up and glitched in the studio.

It’s also supposed to be a celebration of jungle music, a style he was quite enamored with at the time. In the press, he referred to it as “the great cry of the twentieth century”. On tour he split the set into two halves – a rock set and a drum ‘n’ bass set. Critics didn’t like it, and neither did his fans. After he noticed that most of his audience left after the rock set ended, he defiantly put the drum ‘n’ bass set first for the remainder of the dates. Jungle was pretty trendy and oversaturated by this point, which didn’t do him any favours with the cognoscenti. It was as he’d decided in 2001 that rap-metal was the great cry of the twenty-first century.

Regardless, Earthling is aggressive, cartoonish, excessive, and brilliant at times. Most of the tracks speed along like little mechanical rabbits, flurries of breakbeats trying to throw you out of the groove. “Dead Man Walking” proves itself the strongest cut, with a tough KMFDM groove mixed with introspective lyrics: Bowie is pondering his own sell-by date. “Law (Earthlings on Fire)” is also pretty strong, ending the record on an apocalyptic note. The music seems to be blasting from lamppost speakers while chlorine gas swirls below.

“Seven Years in Tibet” is rather long-winded, featuring a kick and snare sample that seems inspired by Iggy Pop’s “Nightclubbing” (or maybe it is that kick and snare! I’m not sure). The song plods along, with massive gravitas, before exploding into an incandescent fireball of guitars. Bowie was a Free Tibet supporter for many decades: “Silly Boy Blue” on his first LP deals with it, and although he forgot about all those early songs, he never forgot Tibet.

“I’m Afraid of Americans” is more KMFDM-sounding material, with Bowie using synths the way he used Ronson’s guitars in the past, as riffs for him to emote over. The song was a rare chart hit in the United States. For the last time, they had to be afraid of him.

Although the two sound nothing alike, Earthling was made in the same spirit as Low. “How can I make human musicians sound like robots?” Low achieved this with motorik, synthesizers, layered drums, and Brian Eno. Earthling uses computers. For the first time, Bowie was cut on ones and zeros. Right around the corner were BowieNet, Bowie Bonds, BowieBanc, and all the rest.

Earthling is a fascinating example of an album that doesn’t particularly want to be loved or hated, just remembered. There was nowhere to go from here. How do you follow up excess? Even more excess? Bowie course-corrected after this with the stripped back …hours, landing so hard back on earth with that he buried the record in the ground. His subsequent records tended to be conservative and calculating, carefully doling out “experimentation” one pinch at a time. Earthling is a special moment: the final time Bowie truly went mad in the studio.

1. Outside is a masterpiece, Bowie’s greatest work in fifteen years, and barring a nanotechnological rebirth, will be his greatest work in the remaining sum of human years. (Sadly, I don’t believe Blackstar finishes as well as it began.)

But it’s exhausting. “Heroes” charges you up, this album drains you dry. The occasional pop song (“I Have Not Been to Oxford Town”, “Strangers When We Meet”) falls like a sweet berry between filth-stained cobblestones of industrial metal, avant-garde jazz, spoken-word interludes, and atonal ambiance. Sometimes the music seems to be reaching too far, and I feel I’m becoming lost. But when the next chord change hits, things always fall back into place.

Some parts I still don’t understand: in particular, the album concept. Something about ritualistic human sacrifice, a private detective, and characters called things like Algeria Touchshriek and Leon Blank. References are made to the “world wide Internet”, and Richard Preston’s alarming 1994 nonfiction book The Hot Zone. Something seems to have happened to this world, an event that Bowie won’t allow us to know. We’re peering through the window, guessing. We’re outside.

Maybe there’s not even a single concept. Like Diamond Dogs, Outside is a musical patchwork quilt, assembled from the wrack of a few different projects. In 1994, Q Magazine asked him for a “week in the life” type diary. Bowie felt that his real life wasn’t quite as exiting as they were probably hoping, so he wrote a fake diary by one Nathan Adler (this diary is reprinted in Outside’s liner notes). Two years earlier, he’d re-united with Brian Eno, and attempted to form a kind of avant-garde supergroup (much of their work eventually saw release on the internet as the Leon Suite.)

In addition to Eno, Bowie has his most powerful lineup in years. Carlos Alomar is back (holy shit!), as is Reeve Gabrels, whose rhythm tracks are distorted to near Static-X levels. Mike Garson makes a very welcome appearance – if you liked the middle fifty-five bars of “Aladdin Sane”, Bowie just gives him six kilometers of rope on this album. He just lays down solo after solo, on track after track, shredding Bowie’s chord progressions with hailstorms of chromatic notes.

The internet, or “information superhighway” (as it was ponderously called in 1995) is a big influence here. Outside seems married to it, somehow. Here’s a David Bowie FAQ from 1996 or so: it’s interesting to read Bowie’s fascination with computers (the digital art accompanying the Q Magazine story was created by him, somehow). Soon BowieNet would exist.

Picking out great tracks is hard, but I really like four. They come in groups of two, each positioned next to each other on the tracklisting (ignoring a segue).

“A Small Plot of Land” is aggressive, ear-bleeding jazz, paying tribute to Scott Walker and nearly upstaging him. “Hallo Spaceboy” is an industrial dance experiment that makes “Pallas Athena” sound like “All of the Dudes”. “Thru’ These Architects’ Eyes” riffs of Thomas Aquinas’s idea of God being an architect, and takes the album to new, celestial heights. And closing track “Strangers When We Meet” is powerful, dark, and tuneful. A perfect song to end on.

Some Bowie albums are best without their context. Outside is best with it. It’s flotsam from a confused and turbulent time in human’s history, when zero started to became one. Bowie was much better than average at predicting the future, but here we see him caught up amidst manifesting predictions – society unease and turmoil, and a digital pantokrator set to pave over humanity with silicon wafer. The album was meant to have a sequel, called Inside. This never materialised, but the wheels of time still turn, and soon we will see Inside for itself.