(Note from management: review is terrible. We estimate that it will be demolished and a better one built by no later than 2039, allowing for cost overruns.)

Here’s where Bowie really gets his shit together. “He already had his shit together on TMWSTW!” Yes, but here he gets his shit even more together. Imagine a 10,000-psi hydraulic shit-compactor that compresses the entire contents of David Bowie’s lower bowel into a one-inch cube. That’s how together his shit is on this album.

Hunky Dory is a lovely collection of music, a classic among classics. Pick a Bowie fan, and ask for their ten favorite songs. I guarantee that at least two and probably three songs mentioned will be from Hunky Dory. (For the sake of sample purity, ignore any female whose answers contains “Magic Dance”.) “Changes”, “Oh! You Pretty Things”, “Life on Mars?”…they just keep on coming, to the point of embarrassment. Damn it, David, you’re supposed give the rubes one good song, and then unload the filler. You’re not supposed to pile up like, four or five classics on each side!

Books could and have been written about why these songs remain listenable and timeless in the face of (ch-ch-)change, bur some of Hunky Dory’s finest moments occur in the the deep cuts. “Andy Warhol” is a song nobody talks about much, and it didn’t place at all in Chris O’Leary’s 2015 Bowie song poll. Yet it contains Mick Ronson’s greatest riff, a jagging, colorful flamenco line that was later borrowed by Metallica for the bridge to “Master of Puppets”. Bowie performed the song personally to Warhol at the Factory in September 1971 – apparently, Warhol completely ignored the song he’d just heard, and commented on Bowie’s shoes!

“Queen Bitch” rips off Velvet Underground and takes them to a new level of violence, pounding the listener into a bloody pulp. But the greatest moment arrives at the very end of the album, with “The Bewlay Brothers”. The song is part acoustic folk, part studio experiment, with a mysterious set of lyrics that fans have spent five decades trying to tease apart.

Bowie would trash the song as portentous nonsense in interviews. But there’s something obviously personal about “Bewlay Brothers”, as if there’s real feelings underneath the fanciful patina of dwarves and rituals. For example, “My brother lays upon the rocks/he could be dead, he could be not” could only refer to Bowie’s schizophrenic half-brother Terry Burns, whose seizures would cause him to collapse in public. Bowie’s disavowals seem like an attempt to cordon off the song, and stop people from looking at it. As a man who traded in identities as much as any spy, did he slip up on this one, and reveal the truth?

Hunky Dory‘s weakness might be the production and presentation. Tony’s Visconti’s absence behind the mixing desk is a pretty big deficit: the instrumentation sounds thin. And although the pacing plays some fun tricks (the unresolved tension at the end of “Oh! You Pretty Things” gets cleared up straight away by the F in “Eight Line Poem”) overall the album seems misweighted, with a foppish, baroque first half and a hard rocking second half.

Although it’s only my fourth favorite Bowie album (behind Low, Station to Station, and Aladdin Sane…or damn it, maybe Diamond Dogs?), it’s the one with the catchiest songs. Bowie ruled the 70s like the Beatles ruled the 60s, but if you were to shave his career to the very finest point, it would start with “I still don’t know what I was waiting for” and end with “…malio”.

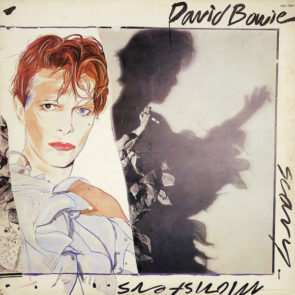

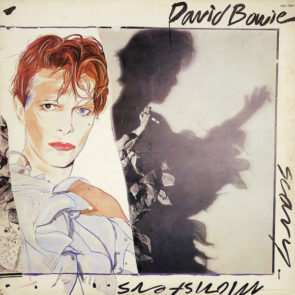

Tonight is widely regarded as the album where Bowie musically fell apart. It is widely regarded correctly.

It puts its best foot forward with “Loving the Alien”, which aspires to be next David Bowie Classic. Yes, move over “Heroes” and “Rebel Rebel”, it’s time for “Loving the Alien”. Does it live up to its ambitions? What do you think? Of course it fucking doesn’t! The production is smothering, the arrangement uninspired, the melodies rancid. The pre-chorus tries to build, but there’s nothing to build from, nowhere to build to. Guitars and glockenspiels and xylophones lurch upwards in awkward quintuplets…then the chorus arrives, at which point everything goes crash on the floor.

The lyrics attempt a grand statement about peace and unity but come off as another white millionaire wondering why all those brown people in the desert don’t try not killing each other. Seven minutes later, the song ends. It’s self-conscious, tries too hard, and just isn’t good.

He phones it in for the rest of the album, and the line’s engaged. “Blue Jean” is catchy and comes off well, although the xylophonist deserves a beating. The rest of the songs just suck, unless you like Phil Collins. The only saving grace is that Bowie is barely on it.

Let’s get that out of the way, too. He plays no instruments, the tracks are propped up with backing vocals and guest performers, and only two tracks are solely credited to him. Five covers on a nine track album, if you please, padding it out to a whopping thirty five minutes. This is the second shortest Bowie album ever released (after Lodger). You could put the entire thing on a 33RPM record, and have enough space a quarter of Aladdin Sane, or “Station to Station” in its entirety. Is Tonight a serious release? It feels more like a posthumous album. It’s as if Bowie died in 1983, and his label went fishing through his rubbish bin for tapes.

I have no more words to say. It’s like reviewing a box of empty air. Call me crazy, but I actually expect David Bowie albums to have David Bowie on them.

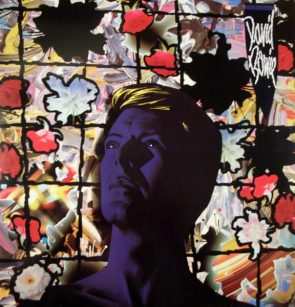

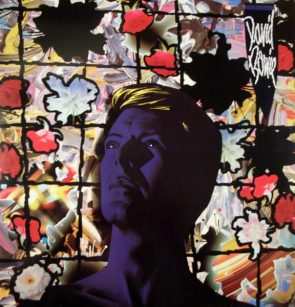

Scary Monsters and Super Creeps is Bowie’s Except Album, meaning it often appears along with the word “except”. “Bowie sucked in the 80s, except for Scary Monsters“. “Bowie was never good when he tried for mainstream success, except for Scary Monsters“, and so forth.

It’s also often spoken about in the same sentence as “scary” and “monsters”. Though that’s less surprising, since that’s the name of the album. It would be strange to talk about the album without mentioning its name, although it would be a fun challenge to do so (and also without identifying it another way, such as “the Bowie album from 1980”). Kafka led a man to the executioner’s block without ever mentioning his crime. Could you arrange words in such a fashion that a reader understands the music, without ever actually being made aware that the album exists?

Scary Monsters is about decay. Not decomposition, not morbidity, just…things falling apart, in a general sense. It’s an album about the crack in your ceiling, and the verdigris embroidering your bathroom floor. All the things you’ve been meaning to fix, even as they advance to an event horizon where it’s not worth the bother.

Bowie assembled some of the finest guitarists to ever set plectrum to string, and made them play sloppily. Vocals are deliberately flat, or mangled oddly in the mixing room (the heavy tremolo rattling the chorus of the title track both disturbs and fascinates). The lyrics discuss fashion and aging, yet they all seem to be about the House of Usher. The building is tumbling down, we’re caught inside it, and we can never leave. Bowie sings about disillusionment and weariness, his voice cracked and broken. None of his albums – not even Aladdin Sane or Outside – evoke this kind of genteel neglect.

“It’s No Game, Pt 1” opens the album in thuggish fashion. Someone took the song, punched it around, and gave it a black eye. Fripp’s guitar part swirls like stagnant water, the drums kick out at you, and it’s interrupted by outbursts of Japanese female vocals, as though someone spliced in the hourly Harajuku traffic report. Although this is the closest solo Bowie ever went to punk rock, it’s cerebral and calculated beneath the blood: more like Public Image Ltd than the Sex Pistols.

Other tracks document various vanishing trends in Bowie’s music. One of the last great Bowie epics (“Teenage Wildlife”) can be found here, as can shorter but equally memorable cuts like “Up the Hill Backwards”. Be sure to get the version with the bonus track, “Crystal Japan”, which was written to score a TV ad for a sake company (of all things) but dredges up strong memories from the Brian Eno years.

“It’s No Game, Pt 2” is a slower and less enthusiastic reprise of the first part. There’s an old Hollywood joke: at eight in the morning you’re shooting Citizen Kane, at eight in the evening you’ll settle for Plan 9 From Outer Space. This song captures that kind of exhaustion and weariness, freezing it under glass.

This album has a reputation as a Bowie threw away most of his artistic pretensions and went fishing for hits. Happily, he caught one (“Ashes to Ashes”). Even more happily, the reputation is wrong: he didn’t throw his artistry very far after all. There’s louche experimental moments all over Scary Monsters. This is the rarest thing: an artistically successful commodity. It’s also one of his most consistent and listenable works. Clearly, the future was bright. He would not put a foot wrong in the 1980s.