British artist Bryan Charnley suffered from paranoid schizophrenia, and in 1991 he painted a series of seventeen self-portraits while on reduced dosages of antipsychotic medication.

The paintings start out normal but soon become weird; broken eggs, free-floating eyes, red throats yawning in foreheads, twitching spiders’ legs, and so on. Frantic pulses of paint irrigate the canvas like blood from a hummingbird’s slit throat, and the final painting is just a collapsed, anguished vortex of color. Charnley’s notes range from calm descriptions of his methods, to rants about “negroes” disrespecting him and TV broadcasts beamed into his mind, to nothing. He committed suicide later that year.

It comes back to one question: what’s it like to be mad? Is there some way that sane people can understand? You can ask a mad person, but can you trust their answer? Maybe not, because their condition might distort how they express themselves. Think of that American POW in that VC propaganda broadcast, claiming he was being treated well by his captors…with his eyes blinking out T-O-R-T-U-R-E in Morse code.

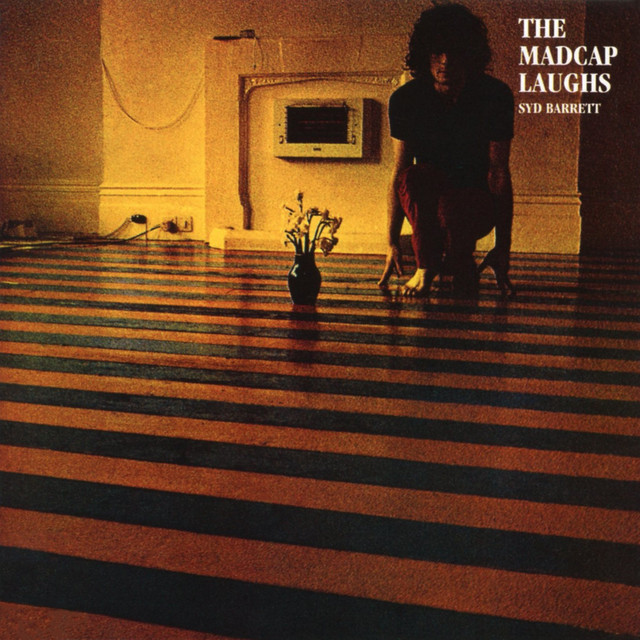

Maybe art is the answer. A recurrent motif in Charnley’s self-portraits is that his lips are nailed shut: he can’t express himself using words, but could use paint instead. Syd Barrett’s 1970 album (created as he was plunging down the slope of his own mental decline) seems like a fascinating example of “mad” art. What can we learn from him?

Well, apparently here’s what being insane is like:

- You will play boring Beatles-sounding skiffle rock.

- Your lyrics will be Dr Seuss rhymes about girls and being in love, or random eructations of nonsense. “Honey love you, honey little / honey funny sunny morning / love you more funny love in the skyline baby / ice-cream ‘scuse me / I’ve seen you looking good the other evening.” And ad nauseaum in that vein.

- You won’t be sure of what key you’re in. “Terrapin” cycles from E major to G major chords. Which is the tonic? If it’s E major, the second chord should be G# major. if it’s G major, the first chord should be E minor. They don’t fit together, and the song flip-flops around without a tonal center.

- The performances will be loose, and not well-recorded. In some songs the main thing audible is Syd’s plectrum. This album apparently took a year to record. It sounds like it was recorded in an afternoon.

- Your album will be padded with stops and starts and count-ins and rambling. Such “authenticity” would become a feature of troubled rock and roll legends, sometimes reaching tragicomic levels, like Having Fun with Elvis on Stage, or Montage of Heck: The Home Recordings (which has tracks of Kurt Cobain burping, making fart noises, and doing a Donald Duck impression). Here, it comes off as mere filler.

- Your mind will shrink, becoming incapable of anything except melodic and lyrical cliches. Madness finally stands revealed not as liberty but as chains.

The most interesting song is “Octopus”. When Syd yawps “Close our eyes to the octopus ride!” he sounds awake and part of the music, instead of (say) like a man groggily trying to put his socks on over his shoes after a three-day Quaalude binge. The Madcap Laughs is otherwise very basic, and it’s almost incidental that Syd Barrett is on it. It doesn’t offer a window into his troubled soul, or a window into anywhere.

The album’s reputation as an oddball masterpiece preceded it, making me look for depths when there weren’t any there. I misheard “Here I Go’s” as “So now I got all I need / She and I are in love with her greed.” That line caught my ear. Why are you in love with her greed? What does that mean? Then I looked up a lyrics sheet: it’s actually “She and I are in love, it’s agreed.” Even my mondegreens are more interesting than the album.

It’s sad what happened to Syd, and I don’t doubt that this album is all he was capable of, but that doesn’t make it good. It’s just skiffle rock mixed with badly played psychedelia. Unlike the work of The Legendary Stardust Cowboy, or the Shaggs, it wouldn’t be remembered at all if a famous person hadn’t played on it.

We need to rethink the cultural idea that crazy people are gifted or special. The Madcap Laughs makes a compelling (rhetorical, not musical) counterpoint: insanity is just flat-out bad. Maybe you can shine on as a crazy diamond, but you can shine far longer and brighter as a sane one. Sometimes life takes things from us, and gives nothing back.

Robin Williams once said “You’re only given a little spark of madness. You mustn’t lose it.” He was speaking about creative madness: not literal madness. In fact, actual insanity is one of the biggest roadblocks imaginable to getting stuff done. It’s horrible, what happened to Syd, and that medical science wasn’t able to stop it. This album is one of the lesser horrors.

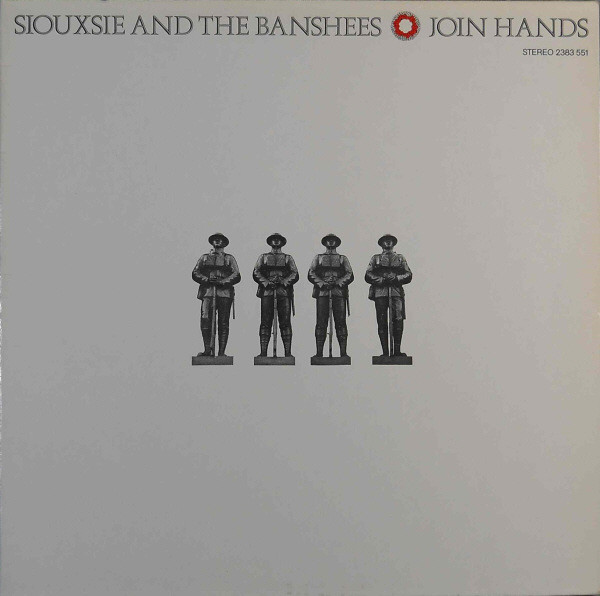

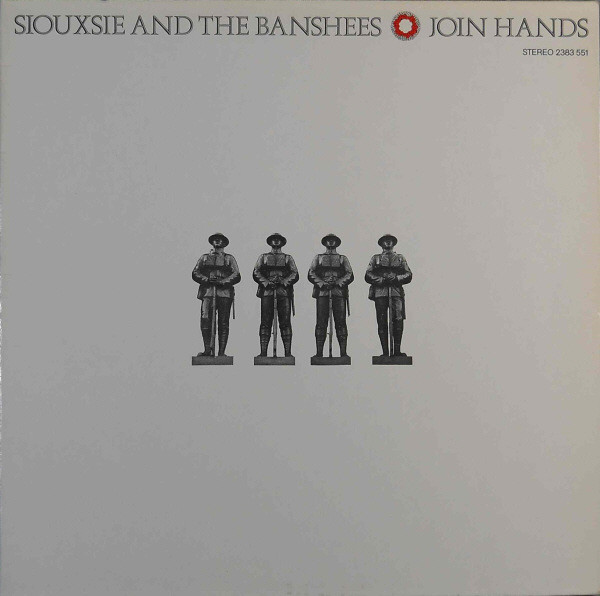

Nobody told me the Banshees were this heavy. Songs like “Regal” and “Icons” rival Killing Joke and Public Image Ltd in cathartic intensity and sheer violence, with Susan Ballion’s voice spiking and cleaving through a white wall of guitar distortion like an ice-axe. They’re the record’s easy-listening songs.

Join Hands proves that post-punk was more than the aftershocks of punk, it was its own movement, and probably a musically more interesting one. Punk was the past’s bitch: 50s rockabilly with a MXR Distortion Plus fuzzbox. Here we’re getting the future, even though we might not want it. You can always predict what the next chord on a Sex Pistols or Ramones song is going to be. You can’t do that on any song here. It’s strange and unfamiliar.

Which is not to say that Join Hands isn’t in debt to the past. “Join hands” is just another way of saying “Come Together”, after all (though now the cover has four soldiers, instead of four self-hating Liverpudlians). Side B contains a reworking of “Oh Mein Papa” (which Eddie Calvert got to #1 in 1954, three years before Ballion’s birth). Musically, it isn’t far removed from what Bowie and Iggy Pop were doing in Berlin in 1977. And on the (improvised) fourteen minute long “The Lord’s Prayer”, Siouxsie Sioux’s lyrics become a filmstrip of old nostalgic references: Bob Dylan’s “Knocking on Heaven’s Door”, Mohammed Ali’s trash talk, nursery rhymes, and the Beatles again (“twist and shout”).

But these images of the past are invariably mocked and desacralized here, their bodies twisted on the torture equipment of Steven Severin’s bass and John McKay’s guitar while High Inquisitor Ballion lays into them. “We have ways of making you talk.” Punk rock was about breaking away from modernistic rock practices and returning to its roots. But in post-punk, the past isn’t deified, it’s investigated and interrogated.

“Icon” has the album (and movement’s?) defining lyric: the church-spire ablaze. Faith tested against flame, and losing. In the real world, John Lennon was shot and Muhammed Ali got Parkinsons and innocuous institutions (parents, schools, and so forth) were sources of misery and even horror for many of us.

And even if the past really was good, you can’t hold onto its pleasures. Your mom and dad are growing old and forgetting your name, your church went into arrears, and your childhood playground was bulldozed long ago. And you’ve changed, too. Your innocence is gone, and you will never see the world as you once did. Time’s geodesic points only forward, and those who try to remain in the past find its memories turning to a pit of gray ash under their tongue.

Join Hands carries a grim message like a lash: there are no roots to go back to, not for rock music or anything else. There is only one possibility left: cold, scientific knowledge. If we never feel pleasure again, we may as well understand what was going on under the hood of concepts like “God” and “health” and “family”. That’s the artistic approach of post-punk: to dissect everything, and not care if it dies in the process.

The Banshees are often more interested in creating spectacles than songs. “Icon” and “Playground Twist” show them at their best: fiery, memorable tracks with huge hooks and apocalyptic thunder. The first is a stately British apocalypse. It has a world inside it, burning from horizon to horizon. The second suspends the listener in a maelstrom of flanging guitar sound and whiplashing meter changes. You feel physically destabilized when you listen to it, as though the ground is collapsing under you.

It breaks ranks with other postpunkers in important ways: the lyrics are precise and literal. Siouxsie feels sincere in her writing, which a refreshing in a genre already known for cloying, unctious irony. “Playground Twist” takes odd material (getting shoved around on a cruel playground where nobody’s your friend) and makes it seem genuinely horrible, the way a child would feel it. The Banshees mean every word here.

At times they go on a bit long, becoming ships lost in squalling noise. I generally skip “Placebo” and “Premature Burial”. They’re just empty boxes of guitar skronk. Occasionally Ballion’s lyrics strike dead notes, particularly on “”Mother / Oh Mein Papa”, where she becomes an angry Dr Seuss. (“The one who keeps you warm / And shelters you from harm! / Watch out she’ll stunt your mind / ‘Til you emulate her kind!”)

Post-punk worked best as a musical stress test. It was about flinging songs into walls, and seeing how and where they break. The subgenre was about exploring limits and failure points, and part of that is wearing out the listener’s patience (and defying their expectation for catchy melodies, etc). That happens a lot here, because Siouxsie and the Banshees want it to happen, but that doesn’t make it any more tolerable.

Strangely, the fourteen minute “The Lord’s Prayer” is among the album’s strong points. The music just explodes out endlessly like a rolling pyroclastic flood, leaving Ballion performing an audacious tightrope-walker’s act over a sea of magma. She pulls ideas out of her head and shrieks them like a human klaxon. I don’t know to what extent it was inspired by “Sister Ray” by the Velvet Underground, but I think the answer is “heavily”.

In some respects Join Arms has aged, in others it hasn’t at all. It’s a backward-looking piece of experimentalism, but the distant past is as unfamiliar as the future. And its focus on World War I is an interesting choice, because it’s one of the clearest clashes of romanticism and realism that culture ever produced. The Armistice that ended World War I was signed at 5:12 am on the 11th of November, but the ceasefire was delayed until 11:00am. This gave the Armistice a gravitas, it was felt. Poets would be able to write that the war ended on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month. Two thousand seven hundred and thirty-eight additional men died so this could happen.

Everyone suddenly burst out singing;

And I was filled with such delight

As prisoned birds must find in freedom

Winging wildly across the white

Orchards and dark green fields; On; on; and out of sight.

Everyone’s voice was suddenly lifted,

And beauty came like the setting sun.

My heart was shaken with tears and horror

Drifted away ….. O but Everyone

Was a bird; and the song was wordless;

The singing will never be done.

- Siegfried Sassoon, “Everyone Sang”

In 2004, Rob Zombie fired his guitarist. This guitarist – who had performed on the multi-platinum Hellbilly Deluxe and had clearly done a lot of the songwriting – immediately formed a new band, Scum of the Earth, along with White Zombie’s Ivan DePrume, and Powerman 5000’s Mike Tempesta.

This kind of “double band” thing is traditionally a way to settle scores and prove who mattered and who didn’t. Would Rob Zombie fail without Mike Riggs? Would Scum of the Earth become the new hotness? Would Bush be re-elected and, if so, would he succeed in “making the pie higher”? These were the questions we asked in 2004.

Spoiler: Rob won. He is still selling out arenas and making movies and touring with balding fifty year old sex criminals. Mike Riggs now works as a tattoo artist. Few remember Scum of the Earth’s inauspicious debut album today, and even fewer will tomorrow.

It deserved better. At least, it didn’t deserve to be totally forgotten. The album is fun. A little cheap sounding, but do you care if liquor comes in a cardboard box if your goal is to get wrecked on it?

Blah…Blah…Blah…Love Songs for the New Millennium demonstrates one thing: the Hellbilly Deluxe sound was indeed Riggs’. You hear it everywhere: the slamming, grooving riffing style, the electronic rhythms, the stop-start dynamics. This is unmistakably the brain (and picking hand) that created “Dragula”. Sometimes the songwriting is uncannily close, such as on album highlight “Murder Song”. When Blah…Blah…Blah… is good (and it is on about half its songs) it sounds far more like Rob Zombie than Rob Zombie’s post-Riggs music, which could be described as “70s nostalgia with about two heavy songs to make the fans happy”.

So what went wrong? Why did the album flop?

Well, larger-than-life shock rock needs a larger-than-life frontman, and Riggs had little charisma or showmanship. Back in the Ozzfest/Family Values days he seemed like a gruesome sideman to Rob, with a hollow acrylic Fernandez guitar that he could fill with blood or rotten meat. But once he had to front his own band he came across as a shy, reticient guy without much to say.

Riggs anti-promoted Blah…Blah…Blah… with truly incredible interviews, such as this one. What makes this project different from any of your previous musical endeavors? “I don’t know…Different people.” What does Rob Zombie think of the band? “I don’t know.” What will you be doing for Halloween this year? “Playing a show somewhere, can’t remember.” He promises to make a second album, and says that it will be “Hopefully, better than the first.”. In a genre where megalomania is virtually a job requirement, this man was hell-bent on discouraging you from listening to his music.

This indifference carries over to the album’s lyrics. Rob Zombie isn’t the greatest lyricist, but he can always be relied on for Burroughs-style lines that send your mind down interesting places. Riggs’ writing is seriously uninspired. Once he’s murdered some sluts and worshipped the devil a few times, he seems to run out of material.

And he cannot sing at all.

He doesn’t have a good voice. That’s the big problem here, particularly as the music is so vocally-driven. He seems to have known it, too: I recall him asking his label to allow him to work with a different singer. They refused, because of some stupid reason that I’ve forgotten and presumably only makes sense to record labels. He should have walked right then. It’s so obvious that this band needed a better singer.

He yelps, slurs, and barks, in a thin and high-sounding voice that’s about three notes deep. The various production tricks (like the way his vox track is slimed up with heavy chorusing) just draw attention to his vocal deficiencies like a blinking engine light.

It gets worse. “Little Spider” and “Give Up Your Ghost” feature acoustic guitars and clean singing. I am proud so say that I have never listened to either song all the way through and I never will.

The production is all over the place. Indie albums often have a fractured, piecemeal quality – they get recorded in various places, when dribbles of money become available – and that’s very apparent here. No two songs are mixed or recorded the same way. The kicks on “Murder Song” are are a healthy +6dB louder than the ones on “Get Your Dead On”. The guitars on “Nothing Girl” have a scooped out Tim Skold/KMFDM character (to the point where they might as well be synths), while “I Am the Scum” sounds like nu metal. The snare drum on “Pornstar Champion” is a digital sample, but the rest of the drums are live.

It’s a bit of a mess. And since Riggs lacks Rob’s major label Rolodex, he can’t paper over his weak spots with guests like Ozzy Osbourne and Tommy Lee and Iggy Pop. A random groupie sings on “Bloodsuckinfreakshow”, along with Riggs’ own son. Apparently the kid agreed to “perform” in exchange for two thousand dollars, terms which Riggs agreed to, on the condition that that the label had to pay him first. They apparently never did, so for all I know, Riggs’ son is still waiting for his two thousand dollars!

So the two big draws of Rob Zombie (the massive production and massive voice) aren’t here. What’s left is Riggs’ musicianship and guitar playing, which carries a lot of these songs. But by the time you get to nothing songs like “Nothing Girl”, you’re just listening to filler. This is a thirty-six minute album that actually runs for about fifteen. It could and perhaps should have been an EP.

I was a big Rob Zombie/Powerman 5000 fan at the time I discovered this – an early version of this site was called The Australian Nightmare, after Rob’s Howard Stern theme song. But this triggered a tyranny of small differences thing in me. There’s nothing worse than a thing you love done just a little bit wrong, and Blah…Blah…Blah… is a lot wrong.

Now that my obsession with Rob Zombie has faded, I can actually appreciate it. It’s forgotten and obscure, but it has its moments, and being dead is no hardship at all for a zombie.