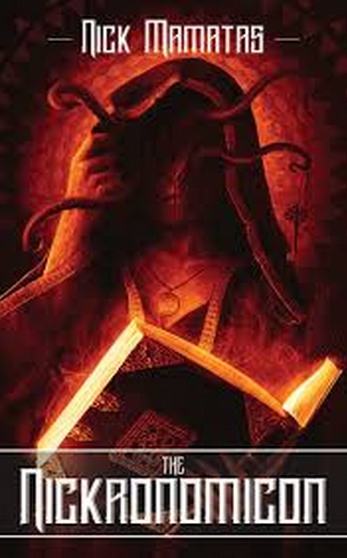

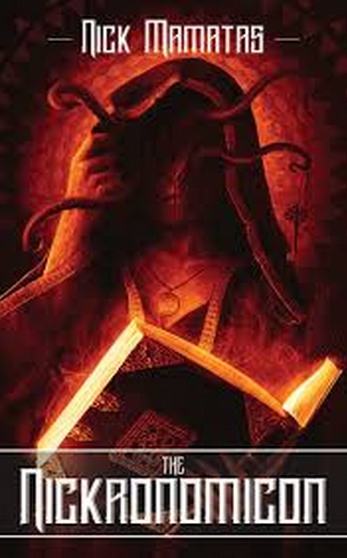

If you’re part of the crowd that wants nothing more than to resurrect Lovecraft and strap a rocket jetpack to his back, then who better to read than Nick Mamatas, Lovecraft superfan par excellence? It’s hard to forget instances like this comprehensive defense of Lovecraft’s prose, and how HPL’s odd word choices like “cyclopean” are actually the ones that fit the scene. It serves as a reminder to never, ever, argue with a superfan about their topic of interest. They’ll make you look like chopped liver.

The Nickronomicon fuses old and new in a way that feels fresh, yet familiar. The familiarity comes from D.M. Mitchell’s impressive but now fairly obscure The Starry Wisdom, another collection that tried to put Lovecraft and postmodernism on the same page (literally), and which I suspect had somewhat of an influence on these stories. One of the Starry Wisdom writers gets a co-writing credit here, for example.

Nickronomicon has all the gore, tentacles, and trans-dimensional spit-swapping you’d expect, but these things share space with Mamatas’s take on the everyman, which are usually writers, downtrodden beatnik types, or fetishistic Lovecraft enthusiasts. At times things get pretty self-referential, with some stories taking potshots at the Lovecraft fandom itself.

“Brattleboro Days, Yuggoth Nights” is a brief but enticing story-through-a-peephole affair that consists of a series of vague and nearly unreadable communications, apparently between HPL and an amateur press enthusiast. Lots of people have tried to the “what if Lovecraft was really on to something?” approach, but I liked this one for its brevity and subtlety. “And Then, And Then, And Then” is even shorter, and revolves around a developmentally challenged person’s encounter with unknown. Again, it’s weird fiction, but there’s a filter in the way – a filter of modernity that doesn’t destroy the weirdness but colors it, makes it seem different somehow.

There’s a fair amount of humor and jokiness. I liked how Mamatas doesn’t treat Lovecraft’s material as fresh virgin snow, but acknowledges that our culture has been strip mining him for more than fifty years (Cthulhu plush toy dolls, and all the rest). The Lovecraft mythos is now shot through with a fair amount of ridiculousness, and he’s not afraid to poke fun at the excesses of fandom, especially in “Mainevermontnewhampshire”, where we see this encounter between a writer and a fan.

“Hi, it’s me,” said the kid, who was actually wearing a tuxedo. “Remember me, from the Lenore Awards banquet, when you won the lifetime achievement award? I wore what I was wearing then in case you came, so you’d remember me.” “You’re my biggest fan,” Sam said. “ … Jeremy?” That was a safe guess. Everyone under the age of thirty seemed to be named Jeremy these days.Jeremy beamed. “You do remember me! I’m so glad I was able to make it. I spent years submitting stories, but finally, one got published. Do you read Dark Somethings, Mister Bey?” It was a photocopied zine that Sam received in the mail every eighteen months or so. He found that the paper stock was good for rolling joints, so appreciated the free subscription.

Ultimately, Nickronomicon rests upon strong and original stories. It’s not the most creative take on Lovecraft, or the best written, but it could end up being one of the most enduring…perhaps because its written by a superfan.

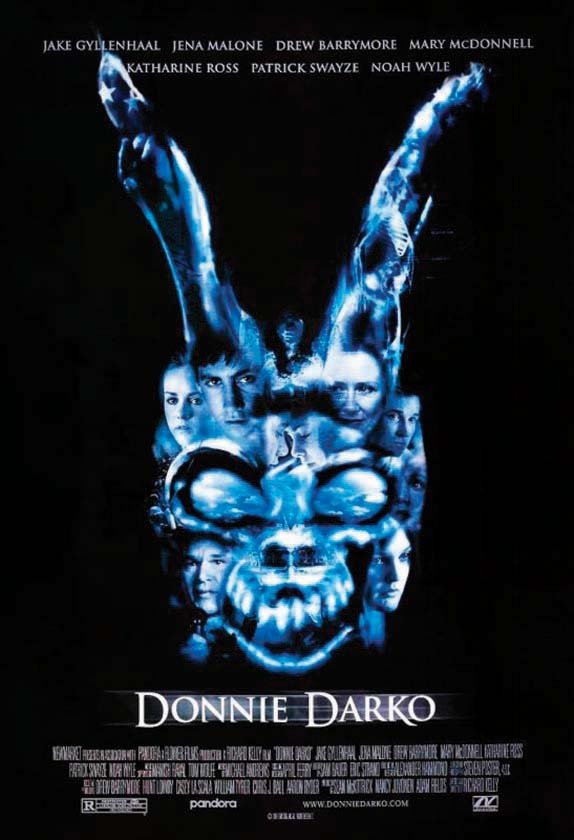

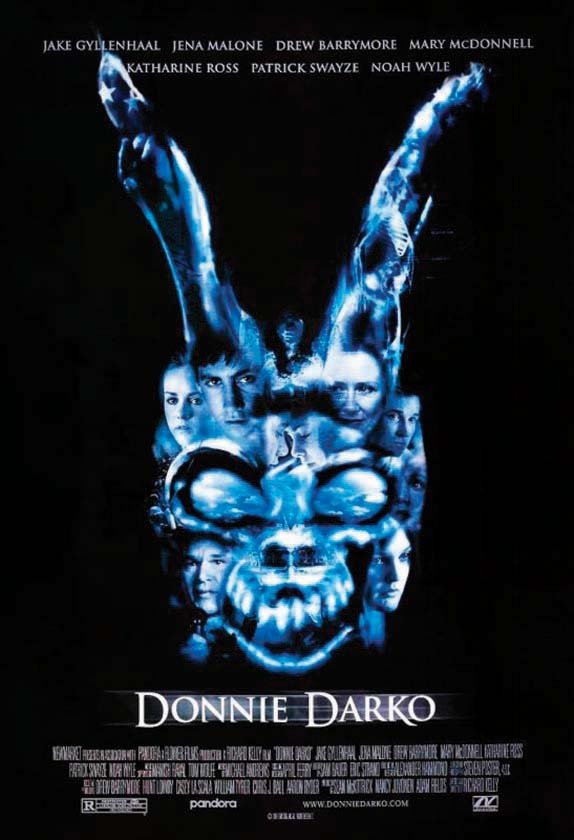

It’s one thing to make a movie that relies on secrets and mysteries, never explaining everything – but then you lose the viewer. Something has to make sense. We get tired of being jerked around. Your movie can’t be the equivalent of a child saying “I know something you don’t know!” for 2 hours. The audience won’t hang around for forever.

It’s one thing to make a movie that relies on secrets and mysteries, never explaining everything – but then you lose the viewer. Something has to make sense. We get tired of being jerked around. Your movie can’t be the equivalent of a child saying “I know something you don’t know!” for 2 hours. The audience won’t hang around for forever.

But the other extreme is equally bad, where a movie anxiously contorts itself into a pretzel trying to “make sense”, killing all imagination and wonder in the process. As the line goes, explaining a joke is like dissecting a frog. You understand it better…but the frog dies.

Donnie Darko somehow combines the bad aspects of both, creating a specious dream narrative burdened that somehow possesses the need to literalize itself with scientific explanation.

The premise is tantalising. A troubled young man is called from his room by a figure in a rabbit suit – this apparent saves his life, for a jet engine crashes into his room as soon as he leaves.

The story soon becomes muddled, and the director’s cut merely shines an extra 10 watt bulb into the murk. Donnie has obviously been saved for a reason…but what? It seems time travel is involved. Something about multiple universes. Donnie travels from place to place at the behest of Mr Rabbit Suit, doing various things, but there’s a layer of confusion preventing them us from seeing the higher purpose. It’s like playing an adventure game when you can’t work out what you’re supposed to do, so you just blindly click on everything in sight.

Donnie Darko has style – all kinds of style. But what, ultimately, is it doing? It’s not a departure into the Land of Lynch – the movie obviously has rules, it’s obviously humming along to some hidden tune we can’t hear. It invites logical analysis…but sadly, logical analysis gets turned away at the door. Sorry sir, you aren’t on the guest list.

It does give an unsatisfying, fairly thin scientific non-explanation for the events in the book. The wonderfully creepy atmosphere is immediately dispersed like fart gas when Donnie starts reading about what’s happening in a helpful textbook called The Philosophy of Time Travel. Stupid. Who thought this was a good idea?

Ultimately, we never know the full story of Donnie’s strange experiences. There are fansites dedicated to explaining this movie, especially its profoundly confusing final scenes. Explanations coil around and around on themselves until you’re left with no choice but to think “why even analyse this? It’s a nonsense. There’s no way, given these facts, to arrive at a consistent conclusion.” Normally you can make any bizzaro version of a theory work by adding enough epicycles and equants, but not here. Where, ultimately, does the aircraft engine come from? The real world, or Donnie’s “tangental” one? Neither makes sense. This movie is impervious to reason.

This movie annoyed me to a degree that probably isn’t healthy. I wonder if the director can furnish answers about this movie. Someone should beat it out of him – my suggestion is with a jet engine.

This album has one bad song. All the others are so good that I keep giving “A Tale that Wasn’t Right” chance after chance, convinced that I must be missing out on its genius somehow. But it remains a bad song.

This album has one bad song. All the others are so good that I keep giving “A Tale that Wasn’t Right” chance after chance, convinced that I must be missing out on its genius somehow. But it remains a bad song.

The rest of the tracks are classic German speed/power metal, with lots of riffs, huge choruses, and a pleasant sense of camp. Helloween is the band that can take you on a 14 minute progressive metal journey, and midway through, you get a lyrical reference to Charles Schultz’s Peanuts. The band’s childlike naivete and sense of humor is genuinely refreshing, and set them apart from a metal scene that was already becoming laughably self-serious.

Kai Hansen is a dominating songwriting force here. His high speed-cookers “I’m Alive” and “Twilight of the Gods” are very fast, the former more agitated, the latter more ambitious and story-driven. “A Little Time” and “Future World” are catchy midpaced rockers, the latter having its childlike melodies cut with creepy brainwashed lyrics – this isn’t power metal as much as Jim Jones metal.

“A Tale that Wasn’t Right” dull and sloppy, but Michael Kiske’s piercing voice is somewhat a point of interest. “Initiation” and “Follow the Sign” are little filler instrumentals that help add a little atmosphere between tracks. The Keeper albums aren’t concept albums as such, unless it’s possible to be a concept album without a concept. The only thing uniting them is the uniting them is the vaguely Nostradamus-like character of the Keeper, who has all of time and space floating within his cowl.

The final song is “Halloween” (A plus two E’s), an incredible recap of Helloween’s (three E’s) career to date: heavy Anthrax-esque thrash riffs, speedy tremolo picking, what seems to be several dozen harmonised guitar solos smashing together in a musical clown car collision, and Kiske nailing ungodly high notes. An astonishing blizzard of speed and technicality that pretty much set the bar on what’s possible with power metal – and yet the songwriting is clever enough that it can be condensed into a 5 minute single while still making sense.

The songs are great, and the lasting impression is one of grandeur, fun, and nostalgia. Sad, too. The Keeper of the Seven Keys diptych came too late to launch them to stardom. Come another couple of years and they’d be a band in ruins – destroyed from the inside by a depressed drummer and egomaniac singer, destroyed from the outside by the advent of grunge rock. By the time they recovered, the window of opportunity was gone. They’re still battling on, without Kai, Kiske, or Schwichtenberg, but they never regained what they’d had before.

With this album nearly twenty years old, its touching to remember the band that was king, if only for A Little Time.