British artist Bryan Charnley suffered from paranoid schizophrenia, and in 1991 he painted a series of seventeen self-portraits while on reduced dosages of antipsychotic medication.

The paintings start out normal but soon become weird; broken eggs, free-floating eyes, red throats yawning in foreheads, twitching spiders’ legs, and so on. Frantic pulses of paint irrigate the canvas like blood from a hummingbird’s slit throat, and the final painting is just a collapsed, anguished vortex of color. Charnley’s notes range from calm descriptions of his methods, to rants about “negroes” disrespecting him and TV broadcasts beamed into his mind, to nothing. He committed suicide later that year.

It comes back to one question: what’s it like to be mad? Is there some way that sane people can understand? You can ask a mad person, but can you trust their answer? Maybe not, because their condition might distort how they express themselves. Think of that American POW in that VC propaganda broadcast, claiming he was being treated well by his captors…with his eyes blinking out T-O-R-T-U-R-E in Morse code.

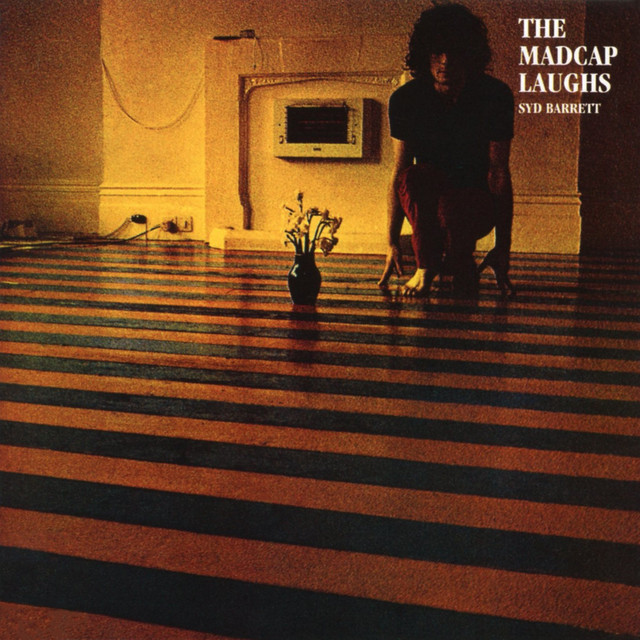

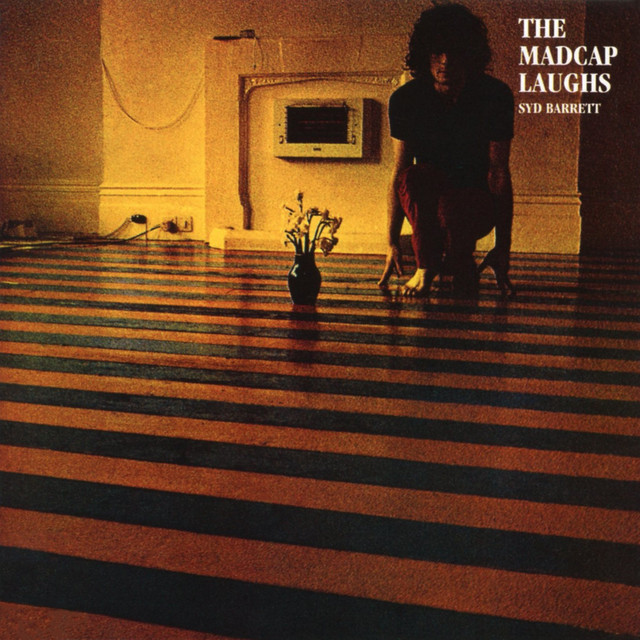

Maybe art is the answer. A recurrent motif in Charnley’s self-portraits is that his lips are nailed shut: he can’t express himself using words, but could use paint instead. Syd Barrett’s 1970 album (created as he was plunging down the slope of his own mental decline) seems like a fascinating example of “mad” art. What can we learn from him?

Well, apparently here’s what being insane is like:

- You will play boring Beatles-sounding skiffle rock.

- Your lyrics will be Dr Seuss rhymes about girls and being in love, or random eructations of nonsense. “Honey love you, honey little / honey funny sunny morning / love you more funny love in the skyline baby / ice-cream ‘scuse me / I’ve seen you looking good the other evening.” And ad nauseaum in that vein.

- You won’t be sure of what key you’re in. “Terrapin” cycles from E major to G major chords. Which is the tonic? If it’s E major, the second chord should be G# major. if it’s G major, the first chord should be E minor. They don’t fit together, and the song flip-flops around without a tonal center.

- The performances will be loose, and not well-recorded. In some songs the main thing audible is Syd’s plectrum. This album apparently took a year to record. It sounds like it was recorded in an afternoon.

- Your album will be padded with stops and starts and count-ins and rambling. Such “authenticity” would become a feature of troubled rock and roll legends, sometimes reaching tragicomic levels, like Having Fun with Elvis on Stage, or Montage of Heck: The Home Recordings (which has tracks of Kurt Cobain burping, making fart noises, and doing a Donald Duck impression). Here, it comes off as mere filler.

- Your mind will shrink, becoming incapable of anything except melodic and lyrical cliches. Madness finally stands revealed not as liberty but as chains.

The most interesting song is “Octopus”. When Syd yawps “Close our eyes to the octopus ride!” he sounds awake and part of the music, instead of (say) like a man groggily trying to put his socks on over his shoes after a three-day Quaalude binge. The Madcap Laughs is otherwise very basic, and it’s almost incidental that Syd Barrett is on it. It doesn’t offer a window into his troubled soul, or a window into anywhere.

The album’s reputation as an oddball masterpiece preceded it, making me look for depths when there weren’t any there. I misheard “Here I Go’s” as “So now I got all I need / She and I are in love with her greed.” That line caught my ear. Why are you in love with her greed? What does that mean? Then I looked up a lyrics sheet: it’s actually “She and I are in love, it’s agreed.” Even my mondegreens are more interesting than the album.

It’s sad what happened to Syd, and I don’t doubt that this album is all he was capable of, but that doesn’t make it good. It’s just skiffle rock mixed with badly played psychedelia. Unlike the work of The Legendary Stardust Cowboy, or the Shaggs, it wouldn’t be remembered at all if a famous person hadn’t played on it.

We need to rethink the cultural idea that crazy people are gifted or special. The Madcap Laughs makes a compelling (rhetorical, not musical) counterpoint: insanity is just flat-out bad. Maybe you can shine on as a crazy diamond, but you can shine far longer and brighter as a sane one. Sometimes life takes things from us, and gives nothing back.

Robin Williams once said “You’re only given a little spark of madness. You mustn’t lose it.” He was speaking about creative madness: not literal madness. In fact, actual insanity is one of the biggest roadblocks imaginable to getting stuff done. It’s horrible, what happened to Syd, and that medical science wasn’t able to stop it. This album is one of the lesser horrors.

“Remember that all worlds draw to an end and that a noble death is a treasure which no one is too poor to buy.”

The beginning of the end: the ape Shift finds a lion skin. Sensing an opportunity, he dresses his donkey friend Puzzle in the skin and has him pretend to be the great lion Aslan.

The crude hoax works, and Shift (who appoints himself as “Aslan’s” spokesperson) is soon Narnia’s de-facto ruler. He fells the forests, enslaves the gullible populace, and throws open the gates to an enemy nation in the south. Worse is coming. In our world the apocalypse will be heralded by four horseman. Narnia gets one, and he rides a donkey.

Where The Magician’s Nephew was the Book of Genesis for Narnia, The Last Battle is patterned upon Revelations. Its plot points – the false prophets, the signs and omens, even the sybaritic decadence of the ape – are drawn beat-for-beat from Revelations and often you can identify the exact chapter and verse. But Lewis does something that John of Patmos doesn’t: he writes affectingly about the psychological devastation caused by the final days.

The book’s best passages describe the confusion and heartsickness of the Narnians under the fake Aslan’s rule. The Great Lion has returned at last…and he’s doing this? Previous Narnian villains (Jadis, Miraz, and Rabadash) were clearly usurpers and outsiders, but now the tyrant is Aslan himself.

The King and the Unicorn stared at one another and both looked more frightened than they had ever been in any battle.

“Aslan,” said the King at last, in a very low voice. “Aslan. Could it be true? Could he be felling the holy trees and murdering the Dryads?”

[…]

Suddenly the King leaned hard on his friend’s neck and bowed his head.

“Jewel,” he said, “What lies before us? Horrible thoughts arise in my heart. If we had died before to-day we should have been happy.”

“Yes,” said Jewel. “We have lived too long. The worst thing in the world has come upon us.”

[…]

“You will go to your death, then,” said Jewel.

“Do you think I care if Aslan dooms me to death?” said the King. “That would be nothing, nothing at all. Would it not be better to be dead than to have this horrible fear that Aslan has come and is not like the Aslan we have believed in and longed for? It is as if the sun rose one day and were a black sun.”

“I know,” said Jewel. “Or as if you drank water and it were dry water. You are in the right, Sire. This is the end of all things.”

The book also has the best villains of any Narnia book, or at least the most villains: Puzzle, Shift, Ginger, Rishda, Tash, and Griffle. Lewis deserves credit for keeping them separate, with their own personalities and motives. Puzzle’s a goodnatured dimwit who redeems himself by the book’s end. Shift’s motives are silly: he’s a glutton who takes over Narnia because he wants more fruit.

“But think of the good we could do!” said Shift. “You’d have me to advise you, you know. I’d think of sensible orders for you to give. And everyone would have to obey us, even the King himself. We would set everything right in Narnia.”

“But isn’t everything right already?” said Puzzle.

“What!” cried Shift. “Everything right?—when there are no oranges or bananas?”

“Well, you know,” said Puzzle, “there aren’t many people—in fact, I don’t think there’s anyone but yourself—who wants those sort of things.”

“There’s sugar too,” said Shift.

“H’m, yes,” said the Ass. “It would be nice if there was more sugar.”

Shift and Puzzle soon end up over their heads and become pawns of the Talleyrandian tomcat Ginger and the foreign warlord Rishda. These two are cynical unbelievers who use the idea of gods to manipulate the Narnians and Calormenes alike. They would have agreed with Seneca that “Religion is regarded by the common people as true, by the wise as false, and by the rulers as useful.”

But Ginger and Rishda are too wise for their own good, because they accidentally summon the Calormene god Tash to Narnia. He’s depicted as a nightmarish bird-headed demon with four arms, evil incarnate. But the book’s most interesting antagonists are Griffle’s band of dwarves, who learn that Shift has been fooling them and resolve never to believe in talking lions again…with the result that they deny the true Aslan when they meet him.

The book could be read as racist and often has been been. Its plot (a white country being overrun by brown-skinned invaders) evokes Jean Raspail’s Camp of the Saints as much as anything, and it was written contemporaneously with the Windrush. It’s possible Lewis intended some sort of political point about immigration.

But it’s not particularly likely, either. The Calormens are a careless blur of vaguely Oriental tropes, their motives are the economic exploitation of Narnia rather than a racial Great Replacement, and their religion (which is polytheistic and involves human sacrifice) seems more like the Aztec one that Islam. Lewis doesn’t really care about them: they’re a McGuffin to support his eschatological metaphor. There are many bad Narnians, as well as a good Calormene soldier. Also, in the post-Narnian afterlife “…Lucy looked this way and that and soon found that a new and beautiful thing had happened to her. Whatever she looked at, however far away it might be, once she had fixed her eyes steadily on it, became quite clear and close as if she were looking through a telescope. She could see the whole southern desert and beyond it the great city of Tashbaan.” So it seems there are Calormenes in heaven, though I doubt they still worship Tash.

The only possibly racist passage comes after Tirian, Eustace, and Jill brown their faces to impersonate Calormenes.

Then they took off their Calormene armour and went down to the stream. The nasty mixture made a lather just like soft soap: it was a pleasant, homely sight to see Tirian and the two children kneeling beside the water and scrubbing the backs of their necks or puffing and blowing as they splashed the lather off. Then they went back to the Tower with red, shiny faces, looking like people who have been given an extra-specially good wash before a party. They re-armed themselves in true Narnian style with straight swords and three-cornered shields. “Body of me,” said Tirian. “That is better. I feel a true man again.”

…But I think the contrast intended by “I feel like a true man again” isn’t Narnian vs Calormen but disguised vs undisguised. Tirian is himself again, instead of pretending to be someone else. Even if it’s not, these words come from a fictional character whose opinions are not necessarily Lewis’s.

The book does provides a window into Lewis’s opinions on various topics. Susan, famously, is not present at the end.

“My sister Susan,” answered Peter shortly and gravely, “is no longer a friend of Narnia.”

“Yes,” said Eustace, “and whenever you’ve tried to get her to come and talk about Narnia or do anything about Narnia, she says ‘What wonderful memories you have! Fancy your still thinking about all those funny games we used to play when we were children.'”

“Oh Susan!” said Jill, “she’s interested in nothing now-a-days except nylons and lipstick and invitations. She always was a jolly sight too keen on being grown-up.”

“Grown-up, indeed,” said the Lady Polly. “I wish she would grow up. She wasted all her school time wanting to be the age she is now, and she’ll waste all the rest of her life trying to stay that age. Her whole idea is to race on to the silliest time of one’s life as quick as she can and then stop there as long as she can.”

Again, take from that what you will. But I co-sign Lewis’s sentiments: your teenage years are the silliest of one’s life and if you have fondness for them I pity you.

We learn about Lewis’s feelings on socialism, which were complicated. Like Orwell, he didn’t see communism and capitalism as necessarily opposed, but two different whips that power can wield. Some of Shift’s tirades could have come straight out of Animal Farm.

“And now here’s another thing,” the Ape went on, fitting a fresh nut into its cheek, “I hear some of the horses are saying, Let’s hurry up and get this job of carting timber over as quickly as we can, and then we’ll be free again. Well, you can get that idea out of your heads at once. And not only the Horses either. Everybody who can work is going to be made to work in the future. Aslan has it all settled with the King of Calormen—The Tisroc, as our dark-faced friends, the Calormenes, call him. All you horses and bulls and donkeys are to be sent down into Calormen to work for your living—pulling and carrying the way horses and such do in other countries. And all you digging animals like moles and rabbits and Dwarfs are going down to work in the Tisroc’s mines. And——”

“No, no, no,” howled the Beasts. “It can’t be true. Aslan would never sell us into slavery to the King of Calormen.”

“None of that! Hold your noise!” said the Ape with a snarl. “Who said anything about slavery? You won’t be slaves. You’ll be paid—very good wages too. That is to say, your pay will be paid in to Aslan’s treasury and he will use it all for everybody’s good.” Then he glanced, and almost winked, at the chief Calormene. The Calormene bowed and replied, in the pompous Calormene way:

“Most sapient Mouthpiece of Aslan, the Tisroc (may he live forever) is wholly of one mind with your lordship in this judicious plan.”

“There! You see!” said the Ape. “It’s all arranged. And all for your own good. We’ll be able, with the money you earn, to make Narnia a country worth living in. There’ll be oranges and bananas pouring in—and roads and big cities and schools and offices and whips and muzzles and saddles and cages and kennels and prisons—Oh, everything.”

“But we don’t want all those things,” said an old Bear. “We want to be free. And we want to hear Aslan speak himself.”

“Now don’t you start arguing,” said the Ape, “for it’s a thing I won’t stand. I’m a Man: you’re only a fat, stupid old Bear. What do you know about freedom? You think freedom means doing what you like. Well, you’re wrong. That isn’t true freedom. True freedom means doing what I tell you.”

“H-n-n-h,” grunted the Bear and scratched its head; it found this sort of thing hard to understand.

The Last Battle seems like almost nothing in summary. Narnia is taken over by the rival state of Calormen, then things get so bad that Aslan ends creation and starts a new one. But the book is hard hitting and emotionally moving, and takes in the Narnia series in directions that are unusual for it, although not unusual for the author.

Lewis actually wrote a fair amount of dystopian fiction. The Great Divorce and The Screwtape Letters contain striking portrayals of hell (the original dystopia), depicting it first as a rainy joyless town and then an absurd bureaucracy. That Hideous Strength is a dry run for George Orwell’s 1984 that depicts Great Britain falling under the spell of rampant NICEness. And in 1956, he swung a wrecking ball through Narnia. It’s a grim end to the series – the plot could be summed up as “everyone dies, plus some asterisks and footnotes” – but it’s an emotionally powerful one. Lewis could have turned Narnia into a production-line franchise like the Famous Five or the Hardy Boys – an infinite-money crank, with Lewis spinning the handle until the magic disappeared. Always Christmas and never winter. But he realized that good things must come to an end. If they don’t, they cease to be good.

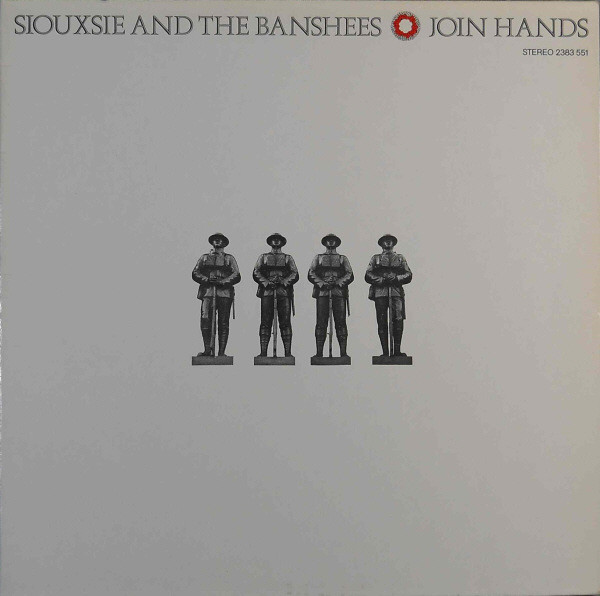

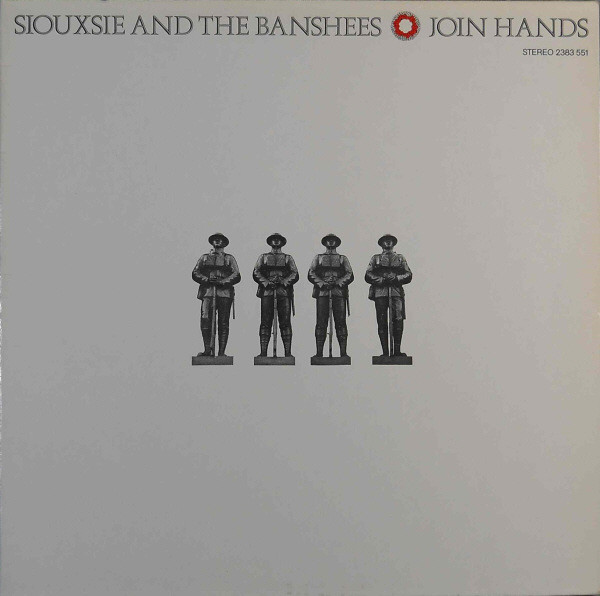

Nobody told me the Banshees were this heavy. Songs like “Regal” and “Icons” rival Killing Joke and Public Image Ltd in cathartic intensity and sheer violence, with Susan Ballion’s voice spiking and cleaving through a white wall of guitar distortion like an ice-axe. They’re the record’s easy-listening songs.

Join Hands proves that post-punk was more than the aftershocks of punk, it was its own movement, and probably a musically more interesting one. Punk was the past’s bitch: 50s rockabilly with a MXR Distortion Plus fuzzbox. Here we’re getting the future, even though we might not want it. You can always predict what the next chord on a Sex Pistols or Ramones song is going to be. You can’t do that on any song here. It’s strange and unfamiliar.

Which is not to say that Join Hands isn’t in debt to the past. “Join hands” is just another way of saying “Come Together”, after all (though now the cover has four soldiers, instead of four self-hating Liverpudlians). Side B contains a reworking of “Oh Mein Papa” (which Eddie Calvert got to #1 in 1954, three years before Ballion’s birth). Musically, it isn’t far removed from what Bowie and Iggy Pop were doing in Berlin in 1977. And on the (improvised) fourteen minute long “The Lord’s Prayer”, Siouxsie Sioux’s lyrics become a filmstrip of old nostalgic references: Bob Dylan’s “Knocking on Heaven’s Door”, Mohammed Ali’s trash talk, nursery rhymes, and the Beatles again (“twist and shout”).

But these images of the past are invariably mocked and desacralized here, their bodies twisted on the torture equipment of Steven Severin’s bass and John McKay’s guitar while High Inquisitor Ballion lays into them. “We have ways of making you talk.” Punk rock was about breaking away from modernistic rock practices and returning to its roots. But in post-punk, the past isn’t deified, it’s investigated and interrogated.

“Icon” has the album (and movement’s?) defining lyric: the church-spire ablaze. Faith tested against flame, and losing. In the real world, John Lennon was shot and Muhammed Ali got Parkinsons and innocuous institutions (parents, schools, and so forth) were sources of misery and even horror for many of us.

And even if the past really was good, you can’t hold onto its pleasures. Your mom and dad are growing old and forgetting your name, your church went into arrears, and your childhood playground was bulldozed long ago. And you’ve changed, too. Your innocence is gone, and you will never see the world as you once did. Time’s geodesic points only forward, and those who try to remain in the past find its memories turning to a pit of gray ash under their tongue.

Join Hands carries a grim message like a lash: there are no roots to go back to, not for rock music or anything else. There is only one possibility left: cold, scientific knowledge. If we never feel pleasure again, we may as well understand what was going on under the hood of concepts like “God” and “health” and “family”. That’s the artistic approach of post-punk: to dissect everything, and not care if it dies in the process.

The Banshees are often more interested in creating spectacles than songs. “Icon” and “Playground Twist” show them at their best: fiery, memorable tracks with huge hooks and apocalyptic thunder. The first is a stately British apocalypse. It has a world inside it, burning from horizon to horizon. The second suspends the listener in a maelstrom of flanging guitar sound and whiplashing meter changes. You feel physically destabilized when you listen to it, as though the ground is collapsing under you.

It breaks ranks with other postpunkers in important ways: the lyrics are precise and literal. Siouxsie feels sincere in her writing, which a refreshing in a genre already known for cloying, unctious irony. “Playground Twist” takes odd material (getting shoved around on a cruel playground where nobody’s your friend) and makes it seem genuinely horrible, the way a child would feel it. The Banshees mean every word here.

At times they go on a bit long, becoming ships lost in squalling noise. I generally skip “Placebo” and “Premature Burial”. They’re just empty boxes of guitar skronk. Occasionally Ballion’s lyrics strike dead notes, particularly on “”Mother / Oh Mein Papa”, where she becomes an angry Dr Seuss. (“The one who keeps you warm / And shelters you from harm! / Watch out she’ll stunt your mind / ‘Til you emulate her kind!”)

Post-punk worked best as a musical stress test. It was about flinging songs into walls, and seeing how and where they break. The subgenre was about exploring limits and failure points, and part of that is wearing out the listener’s patience (and defying their expectation for catchy melodies, etc). That happens a lot here, because Siouxsie and the Banshees want it to happen, but that doesn’t make it any more tolerable.

Strangely, the fourteen minute “The Lord’s Prayer” is among the album’s strong points. The music just explodes out endlessly like a rolling pyroclastic flood, leaving Ballion performing an audacious tightrope-walker’s act over a sea of magma. She pulls ideas out of her head and shrieks them like a human klaxon. I don’t know to what extent it was inspired by “Sister Ray” by the Velvet Underground, but I think the answer is “heavily”.

In some respects Join Arms has aged, in others it hasn’t at all. It’s a backward-looking piece of experimentalism, but the distant past is as unfamiliar as the future. And its focus on World War I is an interesting choice, because it’s one of the clearest clashes of romanticism and realism that culture ever produced. The Armistice that ended World War I was signed at 5:12 am on the 11th of November, but the ceasefire was delayed until 11:00am. This gave the Armistice a gravitas, it was felt. Poets would be able to write that the war ended on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month. Two thousand seven hundred and thirty-eight additional men died so this could happen.

Everyone suddenly burst out singing;

And I was filled with such delight

As prisoned birds must find in freedom

Winging wildly across the white

Orchards and dark green fields; On; on; and out of sight.

Everyone’s voice was suddenly lifted,

And beauty came like the setting sun.

My heart was shaken with tears and horror

Drifted away ….. O but Everyone

Was a bird; and the song was wordless;

The singing will never be done.

- Siegfried Sassoon, “Everyone Sang”