Wow! What a show!

As a father of nine, I can testify (amen!) that it’s a challenge raising Christian children in today’s increasingly secular world. The younger generation is so obsessed with their “iPhones” that they forget the REAL unlimited data plan…prayer! They have Candy Crush on their tablets instead of the 10 commandments. They’re waiting on a “text from bae” when God’s waiting on them to “reflect and pray”. They’re “420 blazing it” when they should be “420 PRAISING it”!

It’s good to know there’s still wholesome Christ-centered animated TV shows out there. Yes, I’ll admit I was nervous when my kids starting watching this. Talking vegetables? And they don’t wear pants? There seemed no end to the perverted possibilities. I’m still trying to repair the damage done to my kids after the The Incredibles 2 exposed them to the words “h*ll” and “d*mn”, and I was eager to avoid another fiasco.

Thankfully, my fears were groundless. This is a marvelous show. Children of all ages will be glued to the screen, laughing at the adventures of Bob the Tomato, Larry the Cucumber, and all their friends. And don’t be surprised if YOU crack a smile – this one’s fun for the whole family!

Yes, sometimes Bob and Larry make mistakes, or act out of impulse. But they always learn a valuable, Christ-centered lesson that kids will take to heart and apply in their own lives. And they’ll never forget that no matter what we do wrong, God is greater than our sins. Amen!

I do question the decision in Where’s God When I’m Scared to write a song discussing the “boogeyman”. As I understand it, the boogeyman is based on a p*g*n diety, and while this might seem harmless it could easily lead to teenage experimentation with dangerous pro-occult media like Dwarf Fortress and Avengers: Endgame. Thankfully, the word is only used a few times and I’ve bleeped it out on my VHS tape.

Yes, it hurts that I have to leave my kids during my lengthy business trips evangelizing the gospel to teenage males inside a San Fran porta potty with a circle cut into the wall. But thanks to this show, I know my children are in good hands – or stems, as the case may be!

In closing: ten out of ten crosses. For once, your children will be wagging their “tales” for the chance to eat their “veggies”!!!

Halley’s Comet is a pale splash of starmilk that runs across the sky every 75 years. As it approaches the sun its frozen nucleus boils, becoming a gaseous tail a hundred million kilometers long.

Some people will see it twice. I expect to only see it once. All celestial phenomena are interesting, but Halley’s Comet is doubly so because it keeps coming back: a friend from space who can’t wait to see us again.

“Is there a point to this?” you ask, perceptive as always. Yes, by reading those words you are a few seconds closer to the Comet’s next appearance (28 July 2061). Here are some more. And some more. You’re welcome. It’s no trouble.

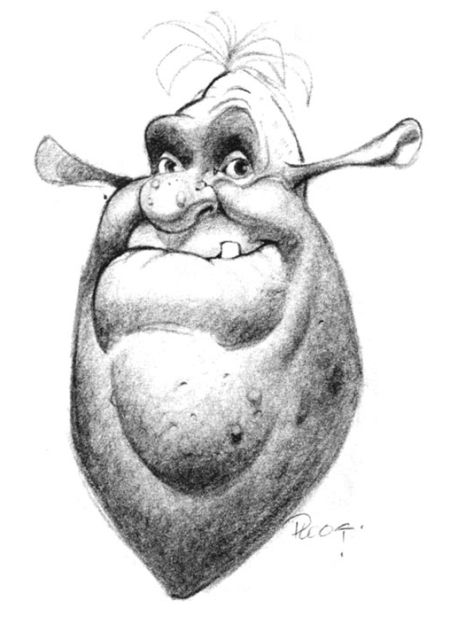

For a month at age 6, my favorite thing was Shrek. For a month at age 11 my favorite thing was again Shrek. Like the comet, Shrek exited and then re-entered my psychic horizon. And just as Halley’s Comet never comes back twice in the same form (it changes shape and albedo as it sublimates mass), Shrek didn’t come back in the same form. The first Shrek! (it had an exclamation point) was a children’s picture book by William Steig. The second Shrek was an animated movie by Dreamworks.

Let’s talk about the book first.

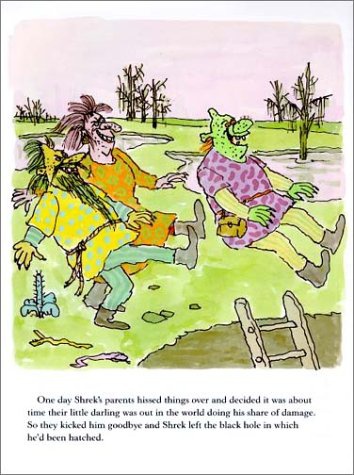

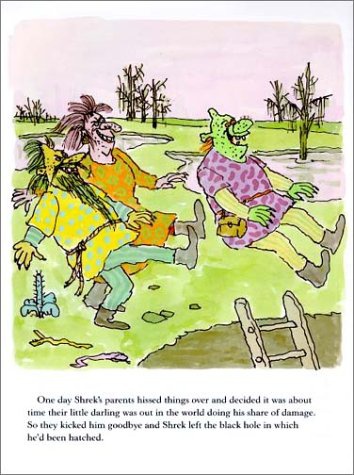

It’s 26 pages of brutal, scabrous art, with thick lines that often don’t join and colors eyedroppered from plates of slime infections. It’s the first time I can recall reading a book and thinking “I could have done a better job on the pictures”. Only later did I realize that “ugly” art can be intentionally so, and that this is some of the most challenging art to produce. There’s a world of difference between shitty drawings and drawings that use shittiness.

The story: Shrek is an revolting creature who roams around scaring people, animals, plants, monsters, and himself (after seeing his own face in a mirror). After being kicked out of home by his parents, Shrek wanders the land, seeking his destiny.

This isn’t a “Shrek’s not ugly, SOCIETY’S ugly for not accepting him! #LoveYourBody” kind of book. No, Shrek’s definitely ugly. Consummately repulsive. Pluperfecty loathsome. Also, he smells so bad that plants and flowers literally bend out of his way.

One of Thomas Aquinas’s arguments for God’s existence (Summa Theologiae 1:2:3) is that the “goodness” concept entails the existence of a maximally good being, ie God. Richard Dawkins has questioned this logic: does the concept of “smelly” require that a maximally smelly being exist somewhere? But after reading Shrek!, I think Aquinas had a point. Shrek is that smelly being.

But is Shrek evil? It’s hard to say. Aside from one clearly bad deed (stealing a peasant’s lunch), most of his actions are morally neutral at worst. He gets in lots of fights, but only because the other person starts them, and he generally incapacitates enemies instead of killing them. He gains the princess’s consent before kissing her, which is something multiple Disney princes don’t do. He has a nightmare about being hugged and cuddled by children, but haven’t we all?

(Update: Halley’s Comet is coming closer. Or further away, rather. It’s complicated, see – it has to reach the far point of its orbit before it starts swinging back. A shortening of temporal distance requires an increase of astronomic distance. The universe is full of such paradoxes.)

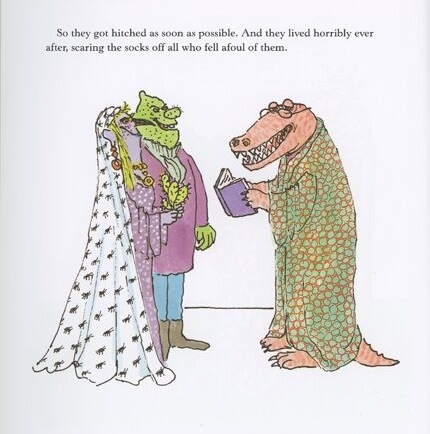

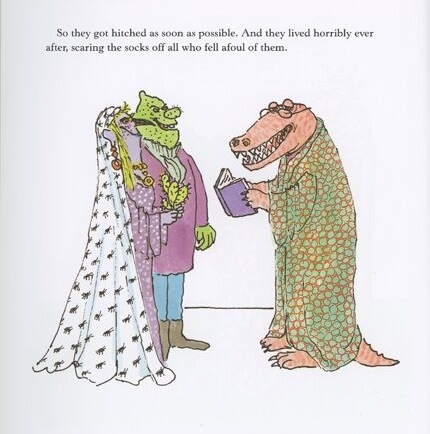

Stieg never “redeems” Shrek, or gives him a makeover, or transforms him into a handsome prince. Shrek is allowed to be what he is and look the way he does, and find happiness in his own way. Many beloved fairytales (the Ugly Duckling in particular) exhibit what Nietzche called slave morality. “You have flaws, but don’t give up! Maybe they’ll magically disappear!”

Well, sometimes they don’t. Shrek! gives it to you straight: you might have to sail the seas of life in adverse conditions. Many adult books don’t confront reality this well.

The book has zero passages describing Shrek as an ogre, by the way. He might be an extremely ugly man. Is there a “Humpty Dumpty is an egg” psyop going on where we collectively agree that he’s an ogre even though it’s not in the book? (Well, the back cover says he’s an ogre. But that’s hardly canon – authors usually don’t write their back blurbs.)

Published in 1990, Shrek! was aimed at preschoolers – although words like “blithe” and “varlet” and “churlish” and “carmine” probably caused some parents to reach for the dictionary. I like the author’s name. Stieg. All of the authors I grew up with had these ominous, evocative sounding names, usually beginning with S. Sendak. Stieg. Seuss. Shel. Stine. Names that made them sound like wizards in high towers, stirring bubbling cauldrons and summoning lightning. Surely no children’s fiction author would have a name like “Bob”.

All in all, a worthy book: Roald Dahl for kids who aren’t old enough for the real Roald Dahl. It’s well worth reading (or re-reading) while you wait for Halley’s Comet. 28 July 2061. Are you excited? I know I am. Soon.

But we still have the movie to discuss.

In 2001, commercials for a film called Shrek began rolling out. Stieg’s book? A distant memory. None of my friends had heard of it.

I saw the movie and it blew me away. I’d never imagined anything so funny, so clever, so sophisticated. This was clearly and inarguably the greatest film ever made.

I talked about it to everyone I could. I had the DVD, and spent hours playing with the special features (if you had a microphone, you could dub your voice over Eddie Murphy’s). If you were my friend and hadn’t watched Shrek, I genuinely thought there was something wrong with you.

I rewatched it in 2021, and it was unimaginably worse than I’d thought.

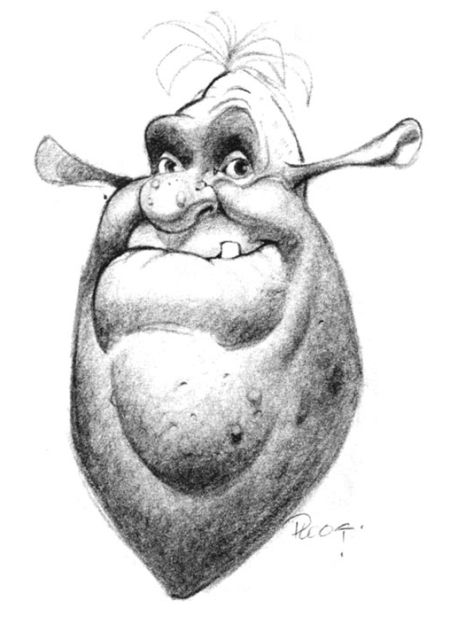

I hated almost every part of it: the plastic doll character design, the bad songs, the cheap pop references substituted for jokes, the “don’t judge people based on appearances!” message interspersed with cruel jibes about how short the villain is. Some computer animated films (Toy Story) have become timeless. Shrek has become ocular pollution: ugly and unfunny.

The movie seems generally well-remembered by others. I wonder how many of those “memories” occurred when the writer was 10, and if they’d survive a rewatch. I made it to the Matrix ripoff scene before mumbling to an empty room “You’re just…commenting on the fact that another movie exists! How is that funny?“

Some parts held up. The opening scene is fun and sells the movie well. There’s sharp writing at certain places (such as the Gingerbread Man sequence). The barely-disguised adult humor (“Lord Farquaad”) isn’t exactly funny but at least shows a creative team with nerve.

But nothing could save the movie from the cancerous pus-filled oozing blastoma sac of Eddie Murphy.

I laughed at the donkey as a kid. Why? He wasn’t saying anything funny. In fact, I barely understood him at all.

Well, because he masterfully created the appearance of being funny. Eddie Murphy is a reminder that much (or most) of humor is in the delivery. His cadence, vocal rhythms, and confidence are flawless, and make him seem like a comedian doing a tight five on national TV and nailing it.

But he’s saying nothing. He was like an air-guitarist performing awesome rock moves with empty hands.

Donkey: [Chuckles] Can I say somethin’ to you? Listen, you was really, really somethin’ back there. Incredible! Yes, I was talkin’ to you. Can I tell you that you was great back there? Those guards! They thought they was all of that. Then you showed up, then bam! They was trippin’ over themselves like babies in the woods. That really made me feel good to see that. Man, it’s good to be free. But, uh, I don’t have any friends. And I’m not goin’ out there by myself. Hey, wait a minute! I got a great idea! I’ll stick with you. You’re a mean, green, fightin’ machine. Together we’ll scare the spit out of anybody that crosses us.

[Roaring]

Donkey: Oh, wow! That was really scary. If you don’t mind me sayin’, if that don’t work, your breath certainly will get the job done, ’cause you definitely need some Tic Tacs or something, ’cause your breath stinks! Man, you almost burned the hair outta my nose, just like the time– [Mumbling] Then I ate some rotten berries. I had strong gases eking out of my butt that day.

Yep, that’s Eddie Murphy in Shrek. Don’t worry, they only let him blather like that for fifty minutes.

It’s clearly improv – a director sat Murphy in front of a mic and told him to go nuts, hoping for another Robin Williams’ Genie. But when the entire movie is littered with this sort of babble, it becomes grating, and then enraging.

The danger of writing a character who annoys other characters is that they will also likely annoy the audience. The 2000s were boom years for black actors with nails-on-chalkboard patter. Will Smith. Chrises Tucker and Rock. Tyler Perry alone is persuasive evidence that we need to means-test microphones before giving them to the black community.

In all, not a good movie.

But there’s a deeper level to all of this. A conspiracy, if you will. As soon as I read item 3 on this list, I heard the X Files theme playing in my head. Mostly because I was playing xfilestheme.mp3 on my computer while reading it.

Douglas Rogers (the art director) found a place there that was a magnolia plantation where he did research to get the look of Shrek’s swamp just right. It was perfect and exactly what he had been looking for, for the film.

While there, though, he was in for quite the big surprise. And that surprise was an alligator, that unfortunately, ended up chasing him.

Once again, this crew’s dedication is something else. Though, I’m sure he wasn’t expecting the alligator to run at him.

All I can say is I hope he felt it was worth every bit of running from the alligator because that is a seriously scary situation to be in all for research for work.

An alligator. In a swamp. One that’s very defensive of Shrek’s legacy. Where have I seen this before?

Damn.

Binding is 10 years old. Aside from the parts that are 45 years old. And also aside from you, the player (I don’t know how old you are).

It’s a slick modern update of the top-down dungeon crawlers people played on mainframes and PLATO systems in the 70s. The classic “roguelike” (as such games were called) consists of an ASCII text world (with your character generally represented by an @), in which you explore dungeons, buy spells, and whack kobolds. They’re one of the oldest game genres and remain influential today – games as varied as Legend of Zelda and Ultima and Diablo could be considered postmodern roguelikes.

The genre’s appeal? Randomness. Early computers had limited data storage and it was actually easier to generate random worlds on the fly using BSP trees than it was to store level data. This also made the games heavily replayable – no two runs of Dungeon or Hack would ever play out the same way – and as Skinner’s 1950s work on operant conditioning demonstrates, randomness itself is addictive. What loot will the next monster spawn? Kill it and find out. Every single fight becomes like Christmas.

Binding is an ugly, degenerate roguelike at heart. You control Isaac, your mother has been commanded by God to sacrifice you, and so you hide from her in the basements beneath your house, which are full of monsters, weapons, health, and other items. If you play well, you gain power, uncover secrets, and perhaps turn the tables on your mom. If you play badly, your cat inherits your loot.

The game is both shallow and deep. While the gameplay loop is simple enough to describe in a sentence – keys open doors, bombs blow up obstacles, killing a boss lets you descend to the next level of the dungeon – the game has hundreds of different items, and it takes a while to learn what they all do. I recommend playing Binding with the Wiki open in another window so you can easily reference the thing you’re about to pick up. It’s often not the case that a pickup will be an unalloyed good – a lot of them have stings in the tail, such increasing your damage while reducing your bullet speed, or giving you extra firepower in exchange for one of your hearts. The game’s loot is also complex in how it interacts with itself. For example, the Cricket’s Body increases your weapon’s rate-of-fire, but this becomes useless if you also have Brimstone equipped, which replaces your weapon with a charge-up beam. A lot of stuff in Binding is situationally good, helping you in only one kind of fight.

Binding is unforgiving. A single wrong choice (such as wasting your last key on the wrong door) can cripple your run. Want to save? You can’t. Want to back out of a losing boss fight? You can’t. You generally don’t know what’s behind the next door – it could be six coins and a heart, or a mini-boss that will stomp your duodenum into the afterlife. This is a 2010 game designed with a 1980 mindset: the player must be abused so that he’ll become a man.

The game’s randomness can make it frustrating as well as interesting. It’s easy to get “RNG screwed” – if you only get useless and unhelpful items from the first couple of floors, soon you’ll be fighting high-level bosses using your starting weapon, which isn’t fun. And certain items seem pretty overpowered. The Unicorn’s Horn can be abused to insta-win every boss fight in the early game, except for Gurdy and Mom. But that’s also part of the appeal, in a weird way. No matter how dire things look, at any moment you might get a god-tier loot drop.

The art style is cute and gross – very “kawaii-gore”. The sound effects are downright disgusting. I don’t know how long the developer spent recording the gurgles and splutters of dying bronchitis patients but hopefully he wiped down the microphone afterwards. The monsters are revolting slimeballs that look like the internal organs evolution mercifully doesn’t allow us to see. Binding has a mid-2000s flash quality (I was overwhelmed by nostalgia by the sight of the Newgrounds logo), and the art assets were clearly designed with an eye towards modding, allowing users to extend the game with their own monsters and items. This is another strength of the roguelikes, which were so basic and minimalistic that it was very easy to spin off a fork of one and turn it into whatever you wanted.

The game draws inspiration from the Biblical tale of Abraham’s “akedah” (or binding) of his son for sacrifice. It seems to be the answer to the question “what did Isaac think of this? And suppose he resisted – what would have happened?” Although religious issues inform the game’s content somewhat, Binding mostly uses Judeo-Christian imagery the same way Hideoki Anno’s Neon Genesis Evangelion does – as a repository of cool and interesting stuff.

The Binding of Isaac is probably one of those games you either play for five minutes or five years, with little middle ground. It’s definitely challenging and “deep”. There’s no shortage of stuff to do, or ways to do it. It’s an overall nice throwback to classic gaming, and Kryptonite for people who save-scum through every game.