Heavy metal is a temple erected in worship of riffs, which are repetitive melodic or rhythmic figures played on guitar. The greatest bands wield them like mystic incantations: songs like Metallica’s “Orion” and Dark Angel’s “Black Prophecies” have such deep, complex, and interesting guitar work that I hope they’ll never end when I listen to them. But it’s possible to overemphasize the riff, and some fans have an almost fascistic relationship with the guitar’s fretboard, with the “trueness” of metal subgenres increasing linearly with how many riffs they have. Dark Angel’s final album famously came with a sticker advertising 246 riffs, like an ad for a cable TV package, and some “cult” bands (Vio-Lence comes to mind) are like laboratory exercises in having riffs and nothing else, with vocals, songwriting, production, and so on being left deliberately casual.

But the riff religion has lukewarm worshippers as well as zealots and fanatics. It also has exploiters (I don’t mean that in a bad sense), and flower metal/melodic power metal bands like Sonata Artica are among them. They’re nominally heavy metal, but they simply don’t care about riffs at all, and metal ideals of “trueness” mean nothing to them. I guess you can’t have a temple – musical or literal – without attracting merchants and moneylenders.

Flower metal first emerged in the early 1990s. Right from the start it didn’t fit in – it was centered around a couple of trailblazing bands (most famously Finland’s Stratovarius and Italy’s Rhapsody) rather than a “scene” as such, and took inspiration more from Yngwie Malmsteen, Ritchie Blackmore, and Johann Sebastian Bach than from Black Sabbath. It achieved a degree of commercial popularity (flower metal is extremely catchy, almost comically so) but it was never respectable, either inside or outside the metal genre. After all, it had no riffs.

Sonata Arctica’s Ecliptica is an album I would have mocked 10 years ago, called “Disney metal”, or whatever. Now, I can appreciate what it’s doing. It’s not perfect, but it’s exemplary. If someone’s not sure what melodic power metal sounds like, show them this. It’s very intense, very catchy, not particularly heavy, and is unembarrassed and exuberant about what it is: a wintry storm of consonance and melody.

Fast songs like “Blank File”, “The 8th Commandment”, and “Picturing the Past” are like being in the path of a VTOL jet’s booster engines – they’re just a nonstop blur of notes, propelled by Tommy Portimo’s 16th note double bass drumming (this had already become a flower metal cliche). “Blank File” is probably the best; Tony Kakko would later regret pitching the key that high: he had tremendous trouble hitting those notes live.

“Kingdom for a Heart” and “My Land” are catchy uptempo rockers, anchored by Tony Kakko’s emotional (sometimes histrionic) vocals and loud/soft dynamics. “My Land” has a great moment where a staccato guitar riff cleaves through in the verse, proving that although Sonata Arctica were heresiarchs, they weren’t above occasionally genuflecting to the riff god. Deeper in the album we get “Full Moon”, which has a degree of lyrical storytelling about lycanthropy. This would cement the wolf as Sonata Arctica’s mascot, as much as the pumpkin is Helloween’s and the dragon is Rhapsody’s.

There’s a couple of ballads, which are overripe and hard to listen to. The band was still learning. They barely had any business playing heavy metal to begin with – their earliest demos (under the name Tricky Beans) reveal a kind of new wave sounding pop band. But their singer, Tony Kakko, discovered Stratovarius, and became briefly obsessed: Ecliptica is a forty seven minute Stratovarius tribute album that actually upstages the band he’s paying tribute to. Stratovarius is fast and virtuostic, but stiff and dead. I like some of their songs, but a lot of it just comes off as slabs of glittering plastic. Sonata Arctica has more life and color.

The album tapers off a little at the end, with “Unopened” and “Mary Lou” sounding like rearrangements of “Kingdom for a Heart”, and “Destruction Preventer” doesn’t have the songwriting to carry it to seven plus minutes. It’s as awkward and unengaging as its title. Nice scream, though.

At least 75% of the album is good to great, which – then and now – is an amazing batting average for melodic power metal. It’s an exhausting style to listen to, and an equally exhausting one to play. Many power metal bands eventually burn out or change styles: Edguy became a glam metal band, Nightwish pushed increasingly into film score and folk music, and Helloween became a dollar-store version of the Beatles for a couple of years. But Sonata Arctica changed styles further (and worse) than most, delving into prog rock, glam, ambient, and even quasi metalcore at points. I don’t like them at all now, and for me Ecliptica is one of the saddest things in music: an early peak.

The Castle of Otranto was meant as a love letter to the past; instead, it inspired the future. The book’s setting—an ancient castle filled with sinister happenings, depraved nobles, and a haunting sense of loss—proved astonishingly popular, inspiring the Gothic literary movement. Books as diverse as Frankenstein, Titus Groan, The Turn of the Screw, Dracula, Northanger Abbey, A Rebours, Interview with the Vampire, the House of Leaves, and even Harry Potter all bear the mark of Otranto and its visions of stone and stain-glass.

The book’s historical setting is loose. Walpole was interested in the High Middle Ages but knew little about them, and Otranto’s castle is haunted by anachronisms as well as ghosts. Characters duel with fencing sabres, which wouldn’t be invented for hundreds of years. The confrontation between Manfred and Theodore is interrupted by the arrival of the “Marquis of Vicenza“, but the title of marquis/marquess/marchese was not used in Italy in the period.

In a literal sense Walpole lived closer to the Middle Ages than we do, but in a scholastic sense he lived further away. Modern medievalists have access to thousands of primary sources, scanned and translated and annotated, but in the 18th century Walpole was limited to whatever books he had in his personal library (or that of Cambridge University, where he studied). 21st century technology gives us a high-powered telescope back to the past; Walpole was forced to peer through cracked, foggy spectacles. He himself complained about the poverty of the existing scholarship. “…The original evidence is wondrous slender.”

But although Otranto never echoes the Middle Ages very strongly, this too became a Gothic hallmark. The genre has a grand, dislocated effect—part history, part myth, part fairytale, part nightmare—that seems to float outside history. It has the slippery heat of an opium dream; the marmoreal coldness of a stone gargoyle. 20th century authors such as MR James and Shirley Jackson were not above turning out minimally-updated variants of the Otranto formula: tense and fraught tales of things that go bump in the night.

The story: despotic tyrant Manfred loses his son in a tragic and absurd accident, on the day the boy was to marry the princess of a neighboring kingdom. He attempts to marry the girl himself, and consummate their nuptials on the spot (perhaps he was motivated by more than desire to preserve his bloodline), but she escapes, leading him on a chase through the vaults of Castle Otranto. He sees things that are not real, and hears creaking sounds when there’s nothing that could be making them. Hanging over this is an ancient prophecy; “”that the castle and lordship of Otranto should pass from the present family, whenever the real owner should be grown too large to inhabit it””. Manfred is doomed. The past—represented by the ancient Otranto castle—is reaching towards him, and it will take from him everything he has.

This is a popular (and perhaps central) Gothic idea: that houses and dynasties, however ancient and grand, all eventually die. Throw a ball in the air, and it will fall. Throw a cathedral spire into the air, and it will fall. Even when the spire is lofted atop a mighty edifice arches, gables, tympanums, archivolts, balustrades, and buttresses, even if it’s sanctified by prayers and the blood and bones of saints, it will still fall. That’s the way of things: they come crashing down. Gravity is inescapable, as is the entropy behind it, and the only certainty is collapse. Gothicism is the literature of dust.

Walpole is modern in his outlook. He plays metafictional games, framing the book as a “lost work” that he is the translator of (needless to say, several of his contemporaries actually thought this was true!). Amusingly, he throws critical brickbats at his own work.

“It is natural for a translator to be prejudiced in favour of his adopted work. More impartial readers may not be so much struck with the beauties of this piece as I was. Yet I am not blind to my author’s defects. I could wish he had grounded his plan on a more useful moral than this: that “the sins of fathers are visited on their children to the third and fourth generation.” I doubt whether, in his time, any more than at present, ambition curbed its appetite of dominion from the dread of so remote a punishment. And yet this moral is weakened by that less direct insinuation, that even such anathema may be diverted by devotion to St. Nicholas. Here the interest of the Monk plainly gets the better of the judgment of the author. However, with all its faults, I have no doubt but the English reader will be pleased with a sight of this performance.”

The story is funny—when and why did Gothic horror decide to be grim and humorless? The scenes where Manfred upbraids his slow-witted castle guards are almost out of Blackadder, and elsewhere Walpole is nearly as pithy and quotable as Oscar Wilde. “A bystander often sees more of the game than those that play”. Again, he appears to be taking the piss out of himself. The “translator” notes that the story contains “no bombast, no similes, flowers, digressions, or unnecessary descriptions.” This is the same story that has hilarious Romantic camp like “The gentle maid, whose hapless tale / these melancholy pages speak; / say, gracious lady, shall she fail / To draw the tear a down from thy cheek?”

Most literary fads are associated with eras, intellectuals, social movements, and locations. Gothicism is somewhat unique in that’s associated with architecture. Although Gothic books can be set anywhere (the memorable Vathek by William Beckford has a Middle East locale), the genre’s most at home in huge, ornate castles.

Why are castles the default Gothic setting? They’re creepy. They’re also useful to the writer. They can plausibly contain secret passages, hidden vaults, deathtraps, dungeons, and so on. And they’re isolated. A castle’s high walls don’t just keep outsiders out, they keep insiders in, and in many Gothic tales they can seem like prisons. The BBC comedy Fawlty Towers derived much of its humor from the gathering tension of these people stuck inside a hotel. It’s a pressure cooker that you know is going to explode. Likewise, the best gothic novels induce a feeling of suffocating tension. And it’s all because of of the castles. It’s like you’re falling into a pit while wearing a stiff suit of armor, unable to move or see or breathe.

It’s pointless recommending Otranto. That presumes it’s possible to not read it, which it isn’t. You’ve already read most of it in the form of countless spiritual descendants. This book is inescapable, standing against the literary horizon like its titular castle:

In 1997, Don Bluth’s Anastasia was a smash hit, earning $140 million at the box office.

His next film, Titan AE, lost a hundred million dollars, ended Bluth’s career as a film director, and bankrupted Fox’s animation wing. What went wrong?

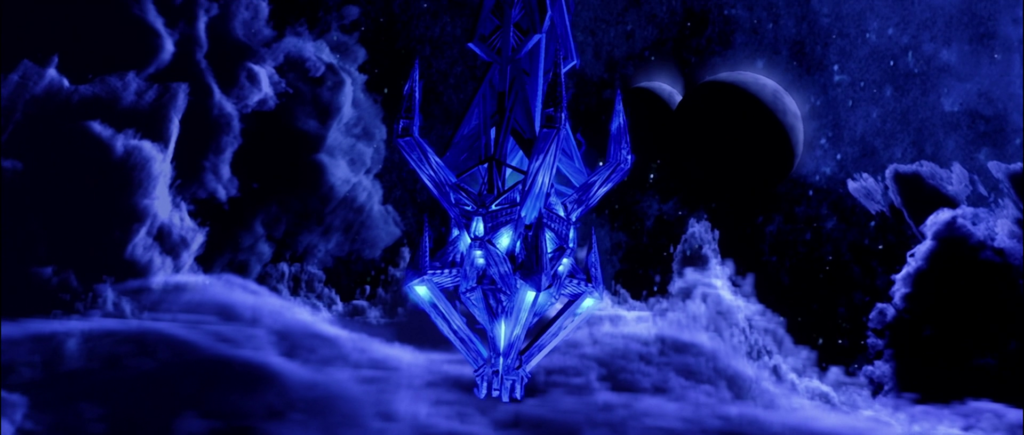

A brief consideration of the film: it’s a science fiction animated feature featuring hand-drawn characters in computer-generated environments. A thousand years in the future, humanity has built a planetary creation device called the Titan, and attracted the attention of a race of energy-based beings called the Drej, who blow up the the Earth. Fifteen years later, the surviving refugees – including Cale Tucker, whose father piloted the Titan away to parts unknown on the eve of destruction – now work as intergalactic miners and scrappers among nearby aliens. It’s a rough universe. If you ain’t got a planet, you ain’t got shit.

The plot is horribly casual and probably a spec script. The narrative is sprinkled with all the expected developments: Cale is sassy and doesn’t fit in, he has to learn to believe in himself, and so on.

The Drej (who are still hunting for the Titan, and believe that Cale is the key to finding it) are blue floating polygons who exist to be gunned down. They’re some of the blandest villains I’ve ever seen. There’s a platonic female love interest who, one gratuitous moment aside (more like Drew BARINGmore, ha ha?), might as well be Cale’s sister. Some depth exists in the charismatic but self-interested Korso, but the film doesn’t know what to do with his complications.

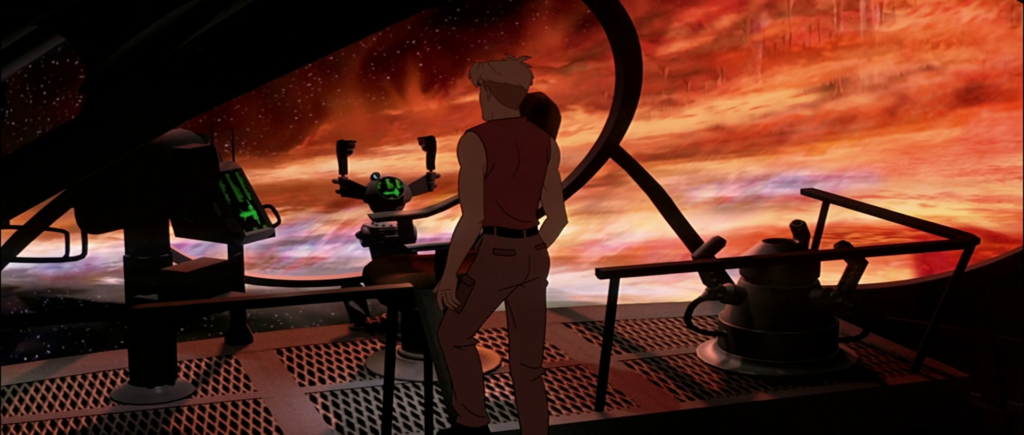

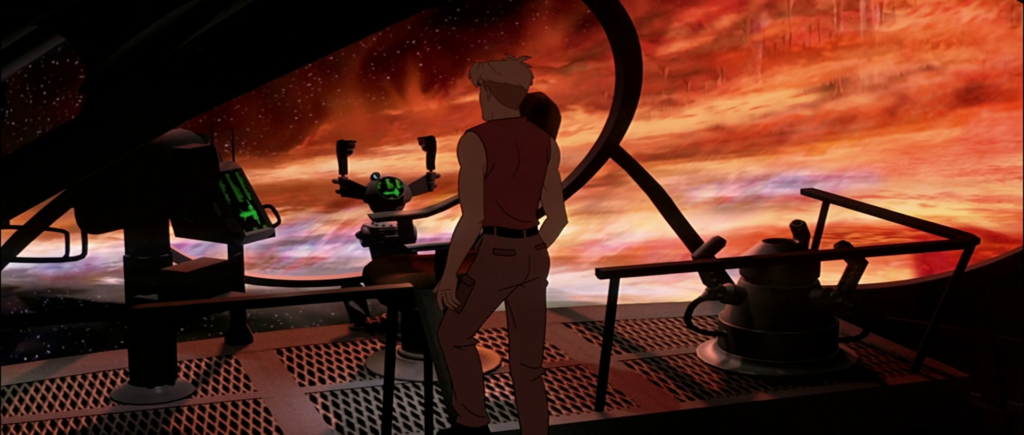

The science fiction setting is Star Wars derived, meaning it’s a WWI/WWII adventure set in space. It’s a world where you can fix up a broken spaceship using spare parts and axle grease. Stowing away on a spacecraft is as simple as hoodwinking a sleepy night guard. Space combat involves dodging laser blasts with a joystick while your attackers ominously beep closer on a green radar screen. It evokes the world of Biggles as much as it does actual space.

Cale’s living quarters contain relics from the lost Earth…but they’re all quaint anachronisms from the 20th century, such as a bisque doll, a hand-cranked camera, and a china cup. The movie seems split between two times. It’s set both a thousand years in the future and a hundred years in the past.

The Titan, when it’s discovered, looks rather like the Death Star, except it creates planets instead of blowing them. Again, spec script. “Borrow ideas from other movies, but twist them so they’re yours”. Likewise, we get Waterworld’s conceit of the hero literally having a map on their body – but instead of a tattoo, the map’s written in Cale’s DNA.

The story didn’t set my imagination on fire, but I’m an adult, and this is a film made for children. Titan AE is edgier than the average Disney film, but that just means its intended audience has an age two digits long. It’s fine to borrow when your audience is encountering most of these tropes for the first time, but it’s a little disappointing, because Titan AE would have worked as an adult film. I don’t mean Heavy Metal style tits and gore. I mean more of a mature, grounded tone, more thought, more wonder, a slower build and a higher climax instead of an endless sugar rush of chases, fights, more chases, etc.

There’s one or two moments where we see the shape of what Titan AE that could have been, like a statue writhing inside a block of marble. I liked the cyberpunk shanty town. And the final scene draws visual inspiration from Moebius’s endless horizon-spanning wastes. But in the end, this aspect of Titan AE is left frustratatingly unexplored. All it shares with the adult animated films of yore is that it made no money.

But storytelling is Titan AE‘s weak point. Its strength is its visuals, which are incandescently beautiful. There’s a ton of great background work, often featuring actual COLOR(tm), which is something Bluth forgets to include sometimes.

The environments are computer-generated, and the way the hand-drawn characters are composited into them is usually extremely well done. This movie does for CGI what Roger Rabbit did for live action – it puts cel-shaded heroes in a computer-generated world, and has them believably take up space and interact with their surroundings.

Look at the above clip: Korso walks up the stairs of the command deck, weaving his body around obstacles in his path. Out of commercially released animated films up to 2000, only Disney’s Tarzan has a better union of computer-rendered and hand-drawn images.

Animation is an odd thing: in theory computers can render anything. In practice (given you have a budget and limited computing power), there are things they can’t easily do. And these limitations are almost the reverse of live action. In live action, it’s hard and expensive to show a car plummeting out of a burning building. In animation, it’s hard and expensive to show a character opening a door, drinking a glass of water, or adjusting her hair. Animation is a game of how easily you can hide your limits, and Titan AE acquits itself well. Not without sacrifices, though. Screenwriter John August remembers having to write the movie around such directives as “the characters can be underwater, but they can’t be wet.”

Titan AE runs into serious problems in its final ten minutes. The film just ends. It’s like the story abruptly files Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

The Titan is discovered, activated, and instantly destroys all narrative tension. Note that the Death Star didn’t belong to the Rebel Alliance, it belonged to the Empire. It’s hard to make a showdown compelling when the heroes have a weapon of literally godlike power – and it raises questions such as “if humanity was capable of building things like this, why were the Drej ever a threat to begin with?”

The movie ends with haunting visuals of a blank slate of a planet – and a new tomorrow for the human race. It’s pretty, but an artificially simple ending, leaving the deeper implications of the plot unresolved.

Even the film’s visuals suffer in the final minutes. Did they run out of time? Money? Both? How else to explain embarrassing shots like this, where the animated passengers look as flat as postcards (and check out the orange background underneath the third man from the left’s face due to a misaligned clipping mask.).

The film might be the fourth greatest Bluth work – worse than An American Tail, A Land Before Time, and the Secret of NIMH, but (slightly) better than Anastasia and All Dogs Go to Heaven, and much better than all the rest (A Troll in Central Park et al). That’s not bad. It could have gone further. A simple and unsatisfyingly resolved story goes a surprising way when it looks pretty. But far enough?

Despite its many strengths, the film capital-f Failed so hard it took down a production company with it. Why?

There’s one explanation: the film was a perpetual pass-along project that nobody wanted to finish, and once it was finished, nobody wanted to promote it.

But there’s a different and more interesting theory, written by Alan Williams on Quora.

One of the better theories I’ve read about this involves the timing and promotion for the movie.

In May of 2000, “Battlefield Earth” was released…and BOMBED. It was critically panned, it did horribly at the box office, and pretty much became a punch-line overnight. This is a film that is routinely mentioned in conversations of “Worst Movies of all Time”.

A month later, “Titan: After Earth” was released.

Fox had promoted “Titan: A.E.” as “Titan: After Earth” quite a bit before it’s release, and well before the release of “Battlefield Earth”. There was a shift in the ad copy to the “A.E.” tag late in it’s promotion cycle, but it was already out there.

So of course, the theory goes that the somewhat similar titles helped to doom the animated movie.

Personally, I give quite a bit of credit to this theory. It’s sort of hard to understate how BIG “BE” bombed. Cratered. It took a lot of folks down with it for quite some time. Franchise Pictures, the production company, was later investigated by the FBI for artificially inflating the production costs of it’s projects, and thus, scamming investors out of their money. John Travolta was said to have fired his long time manager over issues surrounding the film.

Is it true? It’s plausible, but I’m skeptical. I can’t find any pre-release material describing the film as “Titan: After Earth”. And you wouldn’t think Scientology/Travolta vehicles would have a lot of market overlap with fans of Titan: AE.