I wish you could say “he wasn’t crazy, he just played one in his pictures”, but that would be a lie. Artaud was insane. Translator Clayton Eshleman describes his films, poetry, and prose as the partial salvation of a life broken beyond repair, and that cuts to the heart of Artaud: He was a cracked plate, glued together by golden strands of art.

I wish you could say “he wasn’t crazy, he just played one in his pictures”, but that would be a lie. Artaud was insane. Translator Clayton Eshleman describes his films, poetry, and prose as the partial salvation of a life broken beyond repair, and that cuts to the heart of Artaud: He was a cracked plate, glued together by golden strands of art.

Artaud’s life almost feels like a play. It’s full of narratory techniques: callbacks, references, echoes of past events. The amateur electroshock therapy administered by his father in childhood prefigures the far more brutal electroshock therapy he received decades later in a Rodez asylum. A damaging relationship with laudanum prefigures a lethal relationship with chloral hydrate. Artaud’s life has a diegetic quality, a “written” quality, and the sense that things are screeching off the rails into an inevitable tragedy.

“Watchfiends and Rack Screams” collects most of Artaud’s later writings. There’s not much theory, not much organisation, and most of it resembles an opium-deranged brain evacuating and ejaculating over a blank page.

“Artaud, The Mômo” is a typical display, with profane rants going back and forth with tracts of unintelligible gibberish, written in a language I cannot understand or identify.

“To Have Done with the Judgment of God” is a planned radio play that was cancelled the night before it was scheduled to air. It is a twisted, convoluted helix of words, delving into themes both personal and political. “Is God a being? If he is one, he is shit.” Artaud’s relationship with religion was as tumultuous as his relationship with everything else. At certain points, he was possessed with a foul-mouthed, blasphemous kind of heathenism – think the Marquis de Sade with Tourettes. At other points, he tried to become a priest, and compared the Tarahumaran peyote god Ciguri with Christ.

As with everything he does, “entertaining” isn’t the word for it. “Important” is close. “Strong” is closer still. Artaud wrote and did many things that were striking and difficult to ignore, and a decent number of them are collected here.

But was his work ever good? I don’t know. While his work has the impact of bloody viscera on the hood of a car, his contributions to film theory are gnomish and impenetrable, and so is much of his prose. He’s an important figure in surrealistic film and literature, but mostly because he broke things apart – I don’t think he was capable of building them back up again.

Un Chien Andalou is probably the best exposition of Artaudian ideas, and he didn’t make it. Luis Buñuel and Salvadore Dali did.

But here’s a better question: did he ever have the chance to be a great film-maker? No. He was broken, and he couldn’t do anything except document his brokenness. The rock band KISS once had a stage act where bassist Gene Simmons would “fly” around the stage by a crane-mounted hook on his back. One day, the crane broken down in the middle of a gig, and Simmons was left dangling helplessly in the air. He tried to continue his act, scowling and wagging his tongue and breathing fire, but it was soon obvious to everyone that he was a puppet on a string.

Antonin Artaud was like that. He went down into the darkest depths of the psyche without a net, a plunge he ultmately didn’t survive. Heroic? No. Heroism means you have a choice, and Antonin Artaud never had one.

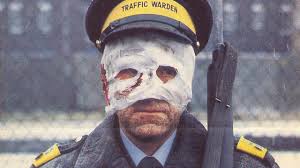

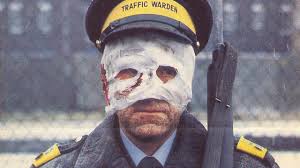

In the 80s, we thought we’d be bombarded by nuclear missiles. Instead, we were bombarded by films about nuclear missiles. The United States initiated this conflict in 1983, with WarGames and The Day After. The USSR retaliated in 1986 with Letters of a Dead Man. The United Kingdom wasn’t slow to unleash its own nuclear missile film arsenal, with Threads exiting the bomb bay doors in 1984 and the animated When the Wind Blows following in 1986. Fortunately, the average film has a very small radioactive footprint, or none of us would have survived.

In the 80s, we thought we’d be bombarded by nuclear missiles. Instead, we were bombarded by films about nuclear missiles. The United States initiated this conflict in 1983, with WarGames and The Day After. The USSR retaliated in 1986 with Letters of a Dead Man. The United Kingdom wasn’t slow to unleash its own nuclear missile film arsenal, with Threads exiting the bomb bay doors in 1984 and the animated When the Wind Blows following in 1986. Fortunately, the average film has a very small radioactive footprint, or none of us would have survived.

“Threads” is probably the most memorable of these films. It traumatized children upon its release, and even now it’s a compelling watch.

The film opens like a sitcom, with a couple in Sheffield decorating their flat. Television broadcasts warn of impeding nuclear war. Usually, sitcoms have to deal with their cast quitting the show, aging out of their role, or getting caught snorting coke. Threads solves the problem by killing almost the entire cast, and a great many people besides.

Soon, the cold war becomes extremely hot, and the world is engulfed by a three gigaton nuclear firestorm. Regrettably, some people actually survive. The rest of the film documents their struggles in the desolate aftermath. Society collapses to subsistence level. Basic wants are in dire need. We start to wonder about genetic mutations and birth defects, and the final scene gives you a lot to think about.

There are a lot of unforgettable images in Threads. A woman cradling a charcoal-black baby. Glass milkbottles instantly flash-melting. A burning cat. After nuclear winter collapses the biosphere, we see a door to door salesman selling dead rats for meat.

The film is almost comically grim, and you start to wonder if it’s supposed to be a parody of nuke films. If it is, it fooled me. I can’t find a single moment where the cast (or director Mick Jackson) winks at the camera – everyone handles the material with dour seriousness.

The BBC’s small budget works well for the film, giving it a filthy, lived-in quality. Sometimes the cheapness adds a new dimension to the horror, as in the hospital scene where open wounds are being sterilized with supermarket containers of Saxa salt.

There’s something intrinsically frightening about nuclear weapons. Perhaps it’s their hopelessness, and the way they knock the traditional rules of war into a cocked hat. Once, better weapons meant you were in a favorable position. Bill has a stick, and uses it to guard his food. Bob has a bigger stick, and uses it to take Bill’s food. So far, so good. But now Bill has a B53, and Bob has a RS-28, and now when they go to war neither of them will win. There will be no Bill, no Bob, and no food to fight over. They’re the most ghastly “off switch” ever achieved. And the only way to prevent their use is to…make more of them?

This is the sort of movie that dirties your TV screen or monitor. You think, your finger will come away coated in dirt and soot. It is a fantastic film that I don’t plan on seeing again, which I think was the goal.

Sacrifice a virgin on an altar and everyone will call you a Satanist, regardless of what god you actually did it for. The Columbine school shootings were blamed on the 1993 videogame Doom. It was theorised that Eric “RebDoomer” Harris had played the game for so long that his CRT monitor had become reality (or reality had become his CRT monitor) and that he was as shocked as anyone that his victims in Jefferson County didn’t bleed red pixels.

Sacrifice a virgin on an altar and everyone will call you a Satanist, regardless of what god you actually did it for. The Columbine school shootings were blamed on the 1993 videogame Doom. It was theorised that Eric “RebDoomer” Harris had played the game for so long that his CRT monitor had become reality (or reality had become his CRT monitor) and that he was as shocked as anyone that his victims in Jefferson County didn’t bleed red pixels.

But in reality, Eric Harris no longer played Doom – he had moved on to Doom’s spiritual sequel, Quake. But nobody accused him of being inspired by Quake, because it was less of a cultural phenomenon and fewer people had heard of it. Just as every random smart-sounding quote gets attributed to Einstein, truth was sacrificed here for maximal memetic transmission. The Quake-Columbine connection was never made, simply because more people knew of Doom. There’s no outrage to be generated from a game nobody in Middle America is aware of.

Quake 2 was even less of a cultural phenomenon than Quake. Nobody has ever attributed any act of violence to it at all. I wonder if John Carmack feels any regret that this is the case, and if I ever plan a spree shooting, I intend to give Quake 2 a shout-out in my shaky-cam Youtube manifesto. You’re welcome, John. Please pay it forward.

Truthfully, Quake 2 deserves a bit more fame, because it’s actually a better game than Quake. It’s not a brilliant shooter. It just takes the strong points of Quake, sticks bandaids over the weak points of Quake, and hopes you don’t notice. Often, you don’t.

The story’s a paragraph in the manual, as usual. Aliens have invaded, ARE YOU A BAD ENOUGH DUDE TO RESCUE THE PRESIDENT, et cetera. But effort has been made to make the gameworld feel like a real place. Spaceships swoop overhead like steel-winged birds. You explore areas with a recognisable purpose (a factory, a mine, a waste processing facility). Environments are somewhat responsive to your actions (you can blow holes in walls and smash panes of glass). Little touches like how enemies duck your shots and switch weapons on the fly are nice. 3D graphics are useless if you still feel like a rat in a maze, and Quake 2 goes a long way towards immersing the player in a believable world.

The weapons and enemies are fun (although there’s nothing as visually striking as the Shambler or the Cyberdemon), and the graphics aren’t that far behind Unreal’s. The game flows well, eschewing obvious “level breaks” for a more unified feel (instead of finishing a level, you walk to a door, experience a brief load screen, and then pick up where you left off.) The soundtrack is excellent. Apparently Sonic Mayhem had no idea how to write metal while he was recording it, and this strangely works. He avoids most of metal’s cliches, just because he’s not aware of them.

The only bad thing you can say about Quake 2 is that it’s a koala bear.

Evolution proceeds stage by stage. If you want C, you first must have B, and if you want B, you first must have A. This approach means there’s not much scope for a wildly novel trait to emerge. You cannot go from A all the way to Z in a single step. If a mutant koala was born with wings, it would be maladapted. Its body shape is not designed for flying. It’s not energetic enough for the rigors of powered flight. Maybe in a few million years a nearly unrecognisable descendant of the koala bear would have wings, but nearly every single one of the animal’s traits would have to change before wings, as a design, makes sense. Which gets bad, considering that the world doesn’t always give you a few million years. Right now, we’re razing the bush. The koala bear’s habitat is disappearing. It’s in a place where it needs an A-Z change, it needs wings, and it needs to modify very quickly or else it will die. But it won’t, because it can’t. Such is the way of evolution. Every strata level of the fossil record is littered with the calcified bones of the ones who died.

Games don’t exactly “evolve” in the way animals do. It is, in principle, possible for a new game with wildly novel traits to emerge. But the majority of games made are basically designed along the principle of “something that sold last season – with a few small tweaks.” Quake 2 fits this description. No drastic steps or changes, just gentle refinement of ideas presented in Quake. And just like real life, sometimes this takes you to an evolutionary dead end. The videogame industry (famously) crashed in 1983, as gamers wearied of generic, low-quality, nearly identical games. They were getting wise to the fact that Ms Pacman was just Pacman with a ribbon and lipstick. Incremental changes don’t work if the entire phenotype can no longer survive.

Quake 2 did not crash the industry. But it’s now very dated, and represents a style of FPS gaming that is no longer in fashion. The commercially viable FPS games are big, cinematic experiences, with Hans Zimmer scores and 3 hours of cutscenes. Quake has a tiny amount of that, but it baby-steps where Half-Life and Deus Ex pole vault.

I’ve played Quake 2’s single player mode a few times, along with some custom levels (the game never inspired the same level of interest in the modding community that the original did, either). It has yielded up most of its secrets. It’s a good game. It’s also a time capsule, and a look into a fossilized past.

I wish you could say “he wasn’t crazy, he just played one in his pictures”, but that would be a lie. Artaud was insane. Translator Clayton Eshleman describes his films, poetry, and prose as the partial salvation of a life broken beyond repair, and that cuts to the heart of Artaud: He was a cracked plate, glued together by golden strands of art.

I wish you could say “he wasn’t crazy, he just played one in his pictures”, but that would be a lie. Artaud was insane. Translator Clayton Eshleman describes his films, poetry, and prose as the partial salvation of a life broken beyond repair, and that cuts to the heart of Artaud: He was a cracked plate, glued together by golden strands of art.