If you had a magic key to somewhere, where would you choose?

If you had a magic key to somewhere, where would you choose?

Fort Knox? The Federal Reserve? That vault where they keep the secret recipe for Coca Cola? If you ever get offered a magic key, here’s my advice: the New York Police Department’s case files.

Perhaps not the most financially remunerative idea, but certainly among the most interesting. And disturbing.

Working backwards through the NYPD’s cold cases is like walking away from the light into a gradually darkening corridor. At the start, a somewhat functional computerized system. Then, typewritten notes and stenotype paper. At the beginning, handwritten police reports, some of which detail unsolved crimes more than a century old.

Much of this stuff has never been digitized. Nobody ever looks at it. I had access to the full files for a brief period of time. For a couple of months, they were my recreational reading.

And yeah, I noticed things.

On January 16, 1938 there was a boiler room accident in Hell’s Kitchen, Manhattan. A leaky valve exploded, flooding the room with steam and killing three people. Two were engineers. One was a girl, between 12 and 16 years of age.

Who was she? That’s the $64,000 question. We’re not sure. One of the engineers’ daughters? If anyone could figure it out, it didn’t make it into the police report. All of their faces were badly disfigured.

The police did find some fingerprints on a doorknob – a big fingerprint, one of the men’s, and a smaller one, presumably the girl’s. These were entered into a database as ID.

On February 28 1964, a train derailed near Newark. This incident’s almost forgotten now, but it made headlines coast to coast when it happened. Dozens were killed. If memory serves, city planner Robert Moses mentioned the incident in his defence of not building a light rail out to Staten Island.

The train’s brakes were found to be faulty. The railway line blamed the subcontractors. The subcontractors blamed the regulators. The regulators blamed the union. Everyone pointed the finger at someone else, except for the volunteers who carted the bodies away. There was no shirking that job.

They did a pretty good job of matching up body parts, but there were some leftovers. A stray piece of skin here. A part of a limb there. Somewhere in that twisted hail of metal, the tip of someone’s finger was cut off and landed in a ditch, a hundred yards away.

Trying to work out whose fingertip it was, they fingerprinted the tip and matched it against various databases.

And got a result so astonishing that many of the people involved simply refused to believe it.

It was a perfect match for the girl who died in the boiler accident in 1938.

This should have been the subject of a much bigger investigation than it was. Everyone involved was too busy digging themselves out of a pile of class-action lawsuits.

The weird duplicate fingerprints were quickly forgotten. Fodder for the National Enquirer and its ilk. And me.

The final incident happened on April 11, 1998.

A fire began on the upper floor of a Queens apartment. It burned for hours, billowing smoke like a Roman candle. After it burned itself out, firemen rappelled in, and found a scorched black interior, and several bodies, cooked to charcoal.

The dying people had left fingerprints on the smoke on the wall. None were very good. Most of them tentatively matched with the family that had been living there, but one was matched with a certain set of fingerprints from 1938 and 1964.

The girl’s fingerprints.

The bodies were too damaged to learn much. Dental records were taken, and one of them seemed a probable match for a girl not younger than 10 and not older than 20. All the tenants recorded as having lived there were in their thirties or older. Again, we have no idea who this girl was.

This fingerprint data is utterly incredible. The NYPD has offered no formal explanation. The final words on the case writeup are “unexplained coincidence.”

And make no mistake, this is something that needs an explanation. Absolutely needs it.

The odds of even two people having the same set of fingerprints are to the order of 1 in 64,000,000. Much less three girls, of a similar age, all living in New York, all dying in New York, all in violent accidents.

But there’s something else going on here that the NYPD hasn’t noticed yet.

January 16, 1938. February 28 1964. April 11, 1998.

See it yet?

These dates are all precisely 11,000 days apart.

I wish the NYPD would get their shit together. I wish they’d fully document and cross-reference all this stuff. With a 21st century system, they might discover additional patterns not even I could find. I wonder if we know where the 1938 girl was buried? If we could get access to her remains, there might be some usable DNA there. We could get some dental records. We could learn so much.

And we could be ready.

Ready for what, you ask? I’m surprised you need to ask.

May 23, 2028.

As I write this, we’re 4,476 days away, and counting.

No Comments »

If western culture is a woman, the 60s counterculture is a tramp stamp tattooed on her ass. It was exciting at the time. As she ages, she’s regretting it more and more.

If western culture is a woman, the 60s counterculture is a tramp stamp tattooed on her ass. It was exciting at the time. As she ages, she’s regretting it more and more.

She wanted to expand her mind. She got a drug problem that exists today, dissolving America’s inner cities like psychotropic acid. She wanted an alternative to the sexual mores of Leave it to Beaver. She got a sky-high divorce rate and a generation of kids raised in dysfunctional “all you need is love” relationships. She wanted new ways of seeing the world. She got Charles Manson and Jonestown. As Peter Fonda said, “We blew it.”

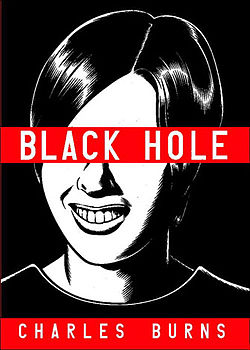

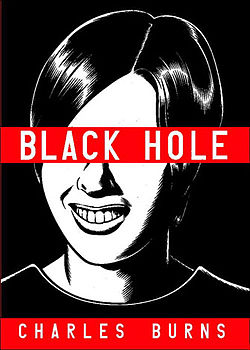

Black Hole is a graphic novel about a bunch of flower power children who are going through changes. Ch-ch-changes. As they immanentize the eschaton with acoustic guitars and reefer, their bodies are starting to transform, their skin melting like congealed fat before a blowtorch.

Sometimes the physical deformities are mild, even photogenic. One girl grows a cute demonic tail. Others look like the Elephant Man. One has pustules erupting on his face like the Yellowstone supervolcano. You’d call him pizza-face, but real pizzerias are never so generous with their toppings. Some have deformities that seem to change with unknowable and perhaps eldritch patterns.

Kid after kid comes down with the “bug”. They all become social outcasts, living on the fringes and stealing from convenience stores. One thing the graphic novel hammers home: being an outcast is overrated. Yeah, disconnecting yourself from the normies sounds great and romantic. In practice, it usually just means a lonelier cage.

Charles Burns art and writing is sparse, and leaves much unsaid. Sometimes it seems like there’s unwritten pages (or perhaps unwritten novels) hiding between his panels. That too seems to evoke a period where revelation was meant to come from within.

It’s confusing and not exactly accessible, partly because of its tone and content and partly because it draws a cultural aesthetic that sunk like Atlantis. The one slight umbilicus to the present (or at least the less distant part) is the character construction. It reminds me a little of that 90s style of cartooning: think Daria, or maybe the work of Mike Diana.

Despite its difficulty, Burns has created a comic about a subject that cannot be explained: the non-religious religions and thoughtless thought-processes of the 60s. It’s an absorbing read, though a hard one. We never find out what it was that caused the deformities: my perspective is that this is something that doesn’t need to be explained. All you need to do is witness it, or at least its aftereffects. Compare and contrast with the medieval plague. Was it cats? Rats? A cesspool of sin rising to the nose of a vengeful God? None of its victims came close to understanding it. But it didn’t matter. In the end, they still died from it.

No Comments »

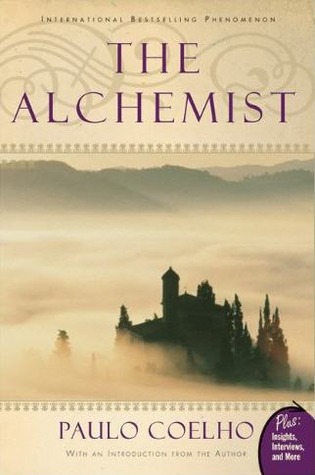

The Alchemist is about a shepherd who receives a dream from God. It’s always a shepherd. If you’re a pig herder in a fable, then aren’t you just shit out of luck.

The Alchemist is about a shepherd who receives a dream from God. It’s always a shepherd. If you’re a pig herder in a fable, then aren’t you just shit out of luck.

Have you ever installed a sound system in a cheap car? The panels shake. The floorboards hum. Each bass hit is accompanied by a dying asthmatic rattle from your car, because the chassis is thin and nothing is spec’d to exact tolerances. It doesn’t matter how expensive the amplifier, speakers, and subwoofer is: you also need a good, solid car to put them in.

I was constantly aware of rattles and hums while reading the Alchemist. I think Coelho is a cheap car – or perhaps he had a poor translator.

Santiago, a young shepherd in Andalusian Spain, begins a journey to find his Personal Legend (portentously capitalized). He gets around a lot. He goes to Morocco, the Sahara desert, and Egypt, while meeting people such as a crystal merchant, an Englishman, and the king of Jerusalem. These were the strongest parts of the book – going places and doing things. The book has a simplicity and directness when relating day to day events that made me wish it had been about someone else, someone unburdened by a dream from God.

But all through the book there’s a falseness to it. It’s partly undone by its need to be a fable, and partly undone by the fact that Coelho never got me to buy into the story. Santiago rides through the desert on a horse named Author’s Convenience. You soon adapt to the book’s approach, and feel no worry or alarm at anything happening: there’s always an amazing stroke of luck around the corner. A fortuitous meeting. A freak meteorological event. Hard to care about Santiago’s fate when you know Paulo Coelho has a skyhook ready to yank him to safety.

Is this the point? That when you trust your life to fate things work out? Who gives a shit? It’s a fictional book – there’s an author operating the gears here. When Santiago receives a pair of stones that allow him to predict the future, you’re not awed by the wonder and whimsy of the universe. You’re aware that this is a MacGuffin in a preconceived plot and that it’s going to be used by Coelho to cheat.

Perhaps the book cleverly (or unintentionally) breaks the fourth wall. Santiago becomes aware he’s a fictional character, and that his author has teleological ends. I think we’d all be a lot bolder if we knew there was a sympathetic author writing our story. But this isn’t compelling reading.

Descriptions are thin and perfunctory. He journeys through the Sahara, but we don’t hear about grit under his fingernails and the agony of climbing shifting sand dunes. Somewhere in the book he meets an Arab girl called Fatima, who he vows to marry once he fulfills his Personal Legend. I don’t recall the part where they discussed the fact that he’d have to convert: Muslim women cannot marry unbelievers.

The book is based off an old Yiddish fable, about a Jew who has a dream about a fortune buried somewhere in Venice. He travels there, digs fruitlessly, until eventually he meets a man who scorns him for his foolishness. “Why, for years I’ve been dreaming of some nonsense about Jew with massive fortune under the basement of his house!”

It’s an interesting premise for a book: a treasure right under one’s nose that you’d have to go around the world to find. Maybe someone is actually searching for treasure right now. If you’re that person, put this book down. It isn’t it.

No Comments »

If you had a magic key to somewhere, where would you choose?

If you had a magic key to somewhere, where would you choose?