Stephen King describes this book as “your basic long scream of horror.” I read it and uttered a basic long scream of boredom. It’s another pandering “wants to be a horror movie” book that does everything except list the names of ideal actors for the film adaptation in the cover sleeve.

Stephen King describes this book as “your basic long scream of horror.” I read it and uttered a basic long scream of boredom. It’s another pandering “wants to be a horror movie” book that does everything except list the names of ideal actors for the film adaptation in the cover sleeve.

Why do I see such a neglect for literature in horror? Literature’s great. Literature rules. Literature can do things and access places that cinema never can and never will, and yet writers almost seem to treat it as a necessary evil on the road to a screenplay. Yeah, books. Those things made of paper. No reason to bother with them, except that sometimes they turn into movies.

In this case, the “film über alles” attitude has resulted in a bare bones, uninvolving story that consists primarily of descriptions of visuals. The story’s totally familiar. A bunch of college kids are on vacation, and instead of a guy in a hockey mask they run afoul of evil plants.

Why plants? Welcome to modern horror: there’s no logic to why anything happens. The book’s floral nemeses are kept shadowy and mysterious, allowing Scott Smith to imbue them with whatever characteristics are convenient at the moment. At one point the vines are drinking the tourists’ blood. At another point they’re imitating the tourists’ speech. Why stop there? Why not have the plants walk around? Everything that happens is totally arbitrary.

Roger Ebert said it very well when talking about Labyrinth. “I have a problem with almost all nightmare movies: They aren’t as suspenseful as they should be because they don’t have to follow any logic. Anything can happen, nothing needs to happen, nothing is as it seems and the rules keep changing. Consider, for example, the scene in “Labyrinth” where Sarah thinks she is waking up from her horrible dream and opens the door of her bedroom. Anything could be outside that door.Therefore, we’re wasting out psychic energy by caring. “

Prose does not carry across into a movie, so Scott Smith doesn’t give much of a shit about it here. It’s written in a bare-bones reportage style with not a word wasted, and not a word put to good use. The book’s horror works at an exclusively visual level, and this sort of thing needs a stabbing orchestral score to be really effective. Nowhere does the prose start to work magic.

The book is overlong and exhausting, with too many scares pitched at the same level, and not enough space to breathe. But it takes several hours to read, while the movie version is just 90 minutes long, so – another indicator of the book being a troublesome, flawed frog, while the movie adaptation is the handsome prince. All that’s missing is the scrolling credits at the end. Fans can recreate the scrolling at home by feeding The Ruins‘ pages to a shredder.

No Comments »

Luke McKinney is an Irish fella who writes annoying clickbait articles for Cracked, mostly of the “I Fucking Love Science” variety. At some point he also started a Twitter account. Unfortunately, chopping his writing into 140-character pieces was not enough to kill it.

Will Self said that Inception was “a stupid person’s idea of what an intelligent film is like.” Luke’s packaged Twitter quips are like that, too. Yes, they resemble jokes. You can find one part that looks like a setup, and then another part that looks like a punchline. But you don’t laugh. They’re always miscalibrated in some way.

He starts strong, then falls off his bike and shits himself. I didn’t react with laughter, I reacted by thinking “A game that realistically models infection and disease might actually be pretty fun. Someone should make one. What was the joke again?”

The tweet is phrased like a smackdown, but since what he’s saying doesn’t make much sense, it provokes confusion, not laughter. He lights the fuse, but the powder is wet. Meanwhile, check out his pandering opinions4u about #feminism.

#FEDORAS #DOUCHEBROS #SOLIDARITY #AMIRITELADIES #BEYONCE #JUSTCLICKTHERETWEETBUTTONPLEASE

As noted, he is a big fan of science…or is he? I sometimes wonder about these “SCIENCE IS FUCKING AWESOME” people. Do they really care that much? Or is it just a badge of identity, like how skinheads wear Doc Martens? Is their professed love of science just a way of feeling special and erudite and above all the other jackoffs regurgitating “rebellious” opinions online that are actually not very rebellious at all? Not that Luke McKinney would feel the need to do anything of the sort.

On the positive side, reading his twitter keeps you a safe OH&S-regulated distance from his articles…and his Oscar Wilde worthy prose…

Research lets you turn your soul into a fascination engine, consuming the output of human intelligence, living and breathing the very pinnacle of human progress. Then reaching out to push it a little bit further.

It lets you “breathe” the “pinnacle” of something, does it? I hope science is FUCKING AWESOME enough to drop a space rock on your head, fag.

No Comments »

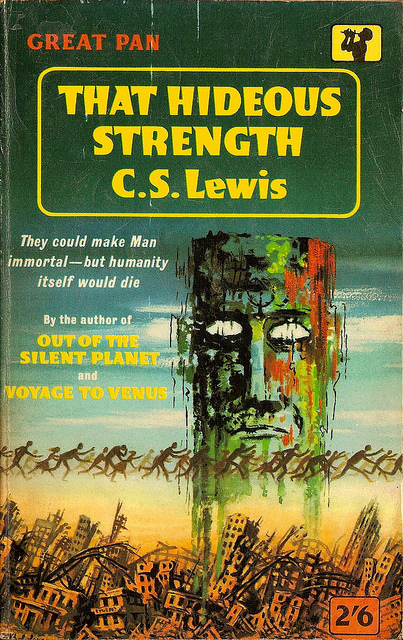

This is Cascading Stylesheet Lewis’s most 1984-like story, with an important difference. 1984 takes place in the middle of the party. That Hideous Strength is about when the party’s just beginning. Lewis, while writing a story about spiritual warfare and cosmic redeption, also outlines how a totalitarian government could believably take power.

This is Cascading Stylesheet Lewis’s most 1984-like story, with an important difference. 1984 takes place in the middle of the party. That Hideous Strength is about when the party’s just beginning. Lewis, while writing a story about spiritual warfare and cosmic redeption, also outlines how a totalitarian government could believably take power.

Technically the third part of the Space Trilogy, it’s probably better read as a standalone book. Nobody goes into space this time. The tone is pessimistic and dystopian. A few characters nominally reappear (a nice shock occurs when you learn Lord Feverstone’s real name), but they seem very different to how we knew them.

The principle character is Mark Studdock, a social climber who gets taken on by an organisation called NICE, which aims to reform and improve society via science unencumbered by ethics. Soon it’s clear that the party is in the thrall of the demonic “eldil” – this is another area where That Hideous Strength is better read on its own. Otherwise you’ll spend many pages patiently waiting for Mark to realise things that have been obvious to you from the beginning.

There’s some vivid and disturbing writing (thanks to NICE, having your head guillotined is no obstacle to your contiunued survival), and a some interesting characters. Lewis stretches himself a little here – there’s a cleric who’s a villain, and an S&M-obsessed female police chief. No swear words, though – Lewis abhorred profanity, and it makes the book’s gritty setting seem false. We also get a romantic relationship rendered in pure tin. Lewis was many things…but he was not a romance writer.

But That Hideous Strength is not a cold book. Here as elsewhere, Lewis finds room amidst religious and sociopolitical issues for humanistic themes that are genuinely moving.

“He looked back on his life, not with shame but with a kind of disgust at its dreariness. He saw himself as a little boy in short trousers, hidden in the shrubbery beside the paling to overhear Myrtle’s conversation with Pamela, and trying to ignore the fact that it was not at all interesting when overheard. He saw himself making believe that he enjoyed those Sunday afternoons with the athletic heroes of Grip, while all the time (as he now saw) he was almost homesick for one of the old walks with Pearson—Pearson whom he had taken such pains to leave behind. He saw himself in his teens laboriously reading rubbishy grown-up novels and drinking beer when he really enjoyed John Buchan and stone ginger. The hours that he had spent learning the slang of each new circle, the assumption of interest in things he found dull and of knowledge he did not possess, the sacrifice of nearly every person and thing he actually enjoyed, the miserable attempt to pretend that one could enjoy Grip, or the Progressive Element, or the N.I.C.E.—all this came over him with a kind of heartbreak. When had he ever done what he wanted? Mixed with the people whom he liked? Or even eaten and drunk what took his fancy? The concentrated insipidity of it all filled him with self-pity.”

The final clash between good and evil has a predictable ending, and Lewis insists on weaving the tale of King Arthur and Merlin into the story for some unknowable reason. Still the unusual setting and interesting characters makes for grim, exciting, and memorable reading.

There’s a newly released edition of this book with annoying cover art – a giant bear, or something. Looks like a bad movie. Past editions have better artwork. Deceptive though it is, you can’t argue that the book is a bit deceptive, too. It barely has anything to do with the rest of the Space Trilogy. Technically it’s the third in a series. Spiritually, it’s distinct from anything else to come from the pen of Lewis. This is a very different book.

No Comments »

Stephen King describes this book as “your basic long scream of horror.” I read it and uttered a basic long scream of boredom. It’s another pandering “wants to be a horror movie” book that does everything except list the names of ideal actors for the film adaptation in the cover sleeve.

Stephen King describes this book as “your basic long scream of horror.” I read it and uttered a basic long scream of boredom. It’s another pandering “wants to be a horror movie” book that does everything except list the names of ideal actors for the film adaptation in the cover sleeve.