The more a monster is written about, the more it becomes the hero. Jason Vorhees was a villain in the first Friday the 13th. By the sixth or seventh, he’d become an icon, an institution, a machete and hockey mask on a t-shirt, with millions of fans cheering when he kills a camper.

Any book on forbidden behavior has to walk the same line. Psychopathia Sexualis: eine Klinisch-Forensische, Krafft-Ebing’s 1886 text on sexual pathology, is written with caution and asperity, clearly afraid that it will inspire as well as inform. It’s a catalog of deviant sexual behaviors, but doesn’t want to be a sales catalog. It hides delicate ideas behind a haze of Latin, and the reader will encounter terms like “paedicatio puellarum” (anal intercourse with girls), and “spuerent et faeceset urinas in ora explerent” (spitting, defecating, and urinating in the mouth).

The book is explicitly “addressed to earnest investigators in the domain of natural science and jurisprudence”. And “In order that unqualified persons should not become readers, the author saw himself compelled to choose a title understood only by the learned.”

These days, the telescope points the other way. Krafft-Ebing’s forbidden fantasies are all over the internet, and many aren’t even forbidden anymore. Now, it’s an interesting look at the 19th century man’s view.

Psychopathia Sexualis sees science shifting from the pre-modern view (where deviancy is caused by sin and moral failure), to the modernist view (deviancy is a pathology under the scope of medicine). There’s even parts where Krafft-Ebing seems to ancitipate the post-modern perspective of Thomas Szasz, where perversions don’t exist: just morally neutral preferences. This is seen in his discussions of “urnings”, or male homosexuals.

The observation of Westphal, that the consciousness of one congenitally defective in sexual desires toward the opposite sex is painfully affected by the impulse toward the same sex, is true in only a number of cases. Indeed, in many instances, the consciousness of the abnormality of the condition is want- ing. The majorityof urnings are happy in their perverse sexual feeling and impulse, and unhappy only in so far as social and legal barriers stand in the way of the satisfaction of their instinct toward their own sex.

There’s still premodernity to Krafft-Ebing’s thinking. Note the “jurisprudence” part of the intro – the book (in part) is meant to assist law enforcement in rendering swift and effective punishment to wrongdoers. He frequently refers to masturbators as “sinners”, and few modern medical textbooks would cite the book of Genesis as a source. But these might be more fig leaves against controversy. Krafft-Ebing is clearly fascinated by these people, and includes copious case notes on sadists, masochists, fetishists of feet and leather and furs, and exponents of rougher trade.

Case 42. A married man presented himself with numerous scars of cuts on his arms. He told their origin as follows : When he wished to approach his wife, who was young and somewhat “nervous,” he first had to make a cut in his arm. Then she would suck the wound, and during the act become violently excited sexually.

The literary work of Baron von Sacher Masoch and the Marquis de Sade are also mentioned. The latter’s works were banned at the time and very hard to find, so I wonder how Krafft-Ebing came to know of them.

Taxil (op.cit.)gives more detailed accounts of this sexual monster, which must have been a case of habitual satyriasis, accompanied by perverse sexual instinct. Sade was so cynical that he actually sought to idealize his cruel lasciviousness, and become the apostle of a theory based upon it. He became so bad (among other things he made an in- vited company of ladies and gentlemen erotic by causing to be served to them chocolate bon-s which contained cantharides)that he was committed to the insane asylum at Charenton. During the revolution of 1790, he escaped. Then he wrote obscene novels filled with lust, cruelty, and the most obscene scenes. When Bonaparte became Consul, Sade made him a present of his novels magnificently bound. The Consul had the works de- stroyed, and the author committed to Charenton again, where he died, at the age of sixty four.

(Is this historical tidbit true? Probably not. Sade published Justine and Juliette anonymously, he wouldn’t have drawn attention to himself with a personal gift of them to Napoleon. Sade was almost destitute at the time Napoleon became Consul anyway, and could ill have afforded expensive gifts. Napoleon committed Sade to Sainte-Pélagie Prison and then Bicêtre Asylum, it was his family that had him moved to Charenton. “Taxil” is likely the proven fraud Leo Taxil.)

Hiram Maxim and Mikhail Kalashnikov lent their names to guns. Sade and Sacher Masoch lent their names to diseases (or so Krafft-Ebing considers them). But that’s the issue at the heart of it all: what’s a disease?

Krafft-Ebing doesn’t seem to know of Darwin, but he gets basically to the same place. Basically, humans have a thing called fitness. We are supposed to survive, and make more of ourselves. Things that get in the way of doing either thing are diseases.

The state of liking blue over isn’t red is not a “disease”. Even if this preference was caused by a brain-controlling bacteria, we wouldn’t call it a disease, assuming that was all it did. It doesn’t impact our fitness.

But male homosexuality is clearly a disease, by a Darwinian standpoint. It reduces reproductive fitness by something like 50-80%. Most would object to calling, mostly because “disease” also has a lot of connotations (that it’s infectious, that it should be cured, etc). I don’t agree. Humans are partly reproduction machines, but also something more: we have a consciousness and a higher goals. There’s nothing inherently wrong with actions that clash with evolution’s “design”, which was largely shaped by chance anyway.

Krafft-Ebing notes that many gay men seem to have artistic gifts.

In the majority of cases, psychical anomalies (brilliant endowment in art, especially music, poetry, etc., by the side of bad intellectual powers or original eccentricity) are present

Suppose that’s true. Would that be a bad disease to have if you deeply desired to be an artist (and lived in a world of in-vitro fertilization?)

I regard homosexuality as a “wrong note” in Darwin’s musical score. Just because something’s technically wrong doesn’t mean we have to regard it as a thing to be fixed. No musician would call a piece of music flawed because it uses non-diatonic notes. Jazz musicians, for example, speak reverently of “blue notes”, which are pitched differently from standard. It all depends on the larger context. Technical deviancy doesn’t imply moral deviancy.

In some cases, the pre-modern viewpoint aligns more closely with the 21st century’s one than it does with Krafft-Ebing. A medieval bailiff would have viewed sodomy (for example) as a choice. An expression of preference. Contemporary culture thinks it’s the same. Krafft-Ebing seems the odd man out by calling it a degenerative pathology.

Here’s another interesting footnote:

I follow the usual terminology in describing bestiality and pederasty under the general term sodomy. In Genesis (chap,xix),whence this word comes, it signifies exclusively the vice of pederasty. Later, sodomy was often used synonymously with bestiality. The moral theologians, like St. Alphons of Liguori, Gury, and others, have always distinguished correctly, i.e., in the sense of Genesis, between sodomia, i.e.,concubittis cum persona ejusdem sexus, and bestialitas, i.e.,concubitus cum bestia (comp. Olfus, Pastoralmedicin, p. 78).

The premodern world actually understood well that bestiality and pederasty are distinct things. It with the Victorian world that blurred them into one undifferentiated sex act. A useful reminder that mankind can seem to progress scientifically, while in fact drawing blinds tighter around the truth.

Sade seems like a good place to end on. “It is a danger to love men, A crime to enlighten them.”

No Comments »

“The Cold Equations” is a deeply hated science fiction story. Nobody writes about Zeno of Elea except to disprove him, and nobody writes about “The Cold Equations” except to spit bile upon on it.

Barry Malzberg:

“The Cold Equations,” is perhaps the most famous and controversial of all science fiction short stories. When it first appeared in the August 1954 issue of Astounding, it generated more mail from readers than any story previously published in the magazine. […] Its impact remains. In the late 1990’s it was the subject of a furious debate in the intellectually ambitious (or simply pretentious; you decide) New York Review of Science Fiction in which the story was anatomized as anti-feminist, proto-feminist, hard-edged realism, squishy fantasy for the self-deluded, misogynistic past routine pathology, crypto-fascist, etc., etc. One correspondent suggested barely-concealed pederasty.

To spare you exposure to hyper-pathological misogynistic crypto-fascist pederasty I’ll summarize the plot. A spacecraft is transporting medicine to a frontier colony. Far too late, the pilot discovers a stowaway on board – a young girl who wants to visit her brother. She has signed her own death warrant: the spacecraft only had enough fuel for one person. The girl’s added mass will kill them both when they decelerate (and then the sick colonists will die without medicine), so the pilot blasts her out of the airlock.

To him and her brother and parents she was a sweet-faced girl in her teens; to the laws of nature she was x, the unwanted factor in a cold equation.

“The Cold Equations” is, essentially, a trolley problem. Can the killing of a fellow human ever be morally justified? If so, how do you weigh one person’s life against another?

It’s a troubling issue with no obvious moral high ground. Should a lawyer die instead of a clown because the clown creates more happiness? Does a life that began at 2:15am have priority over a life that began at 2:14am on the same day? Do you refuse to choose at all (or is that refusal itself a choice?) Any possible solution produces edge cases that seem absurd, arbitrary, or abhorrent.

The story kicks against classic sci fi’s can-do-it optimism, where science and technology is a combination of Jesus, wonderbread, and duct tape . In the real world, it’s not that simple. Sometimes all technology does is drag tissue-fragile men and women into places where nature didn’t intend for them to go, places where they’ll die horrible.

Science looms over the coffin as well as the cradle, offers snakes as well as ladders. Soyuz-11 was a technological marvel, a skirt of aluminium and kevlar laced around the most advanced equipment of its age. It wasn’t enough. The capsule failed to seal, the chamber depressurized, and at that moment, there was nothing that could be done for the three men aboard, nothing at all. “God himself can’t sink this ship!” No, but we can.

“The Cold Equations” is a disturbing and important story, presaging the New Wave in some respects.

Yet I would almost describe it as “universally loathed”.

Start with its Wikipedia page, which is like those WP:Coatrack articles where the “Controversy” section is twice as long as the rest of the article. Aside from a synopsis (and list of adaptations), nearly everything is a link to someone criticising the story.

Then go to the TVTropes page, which is loaded with gems like.

Ass Pull: The lengths this story takes to doom the girl get so outrageous (as noted on the main and Headscratchers pages) that it sounds like a death trap. […] most discussion surrounding the story focuses on the ridiculous contrivances necessary to create the situation in the first place, such as the incredibly short-sighted design of the spaceship, the fact that we are told every piece of it is absolutely essential and indispensable but it contains many features which are not, and the extremely lame security protecting it. […] The whole situation could have been avoided by a 30-second pre-launch check. Or, you know, maybe a lock on the door? […] The author obviously had no perspective whatsoever on how a decent engineer thinks. […] If the premise can’t survive even basic analysis, than its a bad premise.

“The Cold Equations” has produced a small genre of response stories (including “The Cold Solutions” by Don Sakers, and “The Cold Calculations” by Aimee Ogden), written as if “The Cold Equations” is, like Lovecraft’s racism, a stain to be expunged.

I don’t consider “The Cold Equations” to be a SF masterwork. It has a lot of superfluous detail, it’s maudlin and overwrought (a young girl in danger is a tug at the heartstrings, and giving her a cute white kitten called Flossy is ripping them out with a chainfall), and the tragedy is so obviously stark that we don’t need pages of characters sobbing and feeling sad: that actually weakens the emotional impact!

But most “The Cold Equations” critics don’t condemn it on those grounds. Instead, they find the story unfair, as though Tom Godwin (and editor John W Campbell) cheated somehow.

The most common criticisms:

“The story is arbitrary! The author designed the circumstance so that the girl HAS to die!”

Yes, and?

Apparently it’s news that stories are fictive constructs imagined by writers. Here’s Cory Doctorow, bearing the profound insight that fiction is made-up.

The parameters of ‘‘The Cold Equations’’ are not the inescapable laws of physics. Zoom out beyond the page’s edges and you’ll find the author’s hands carefully arranging the scenery so that the plague, the world, the fuel, the girl and the pilot are all poised to inevitably lead to her execution. The author, not the girl, decided that there was no autopilot that could land the ship without the pilot. The author decided that the plague was fatal to all concerned, and that the vaccine needed to be delivered within a timeframe that could only be attained through the execution of the stowaway.

It is, then, a contrivance. A circumstance engineered for a justifiable murder.

It’s a “contrivance”, because all stories are contrived. The word “fiction” itself comes from the Latin fingere (“contrive”). Stories don’t grow on trees; they’re created by writers. It’s absolutely bizarre to criticize a story for being driven toward an intended conclusion. That’s why we read stories! If you want to see a meaningless swirl of random events, stare at a lava lamp.

It’s also unclear what ending Doctorow would prefer: a story where the girl lives would be equally contrived (and would have ruined the message, turning it into a hokey Corman B-movie plot about a pilot and teenage girl on a spaceship). He might mean that “The Cold Equation” is unbelievable: it depicts events incongruous with reality to the point of ruining our suspension of disbelief. That would be a good point. If nothing seems real, then whatever message the author intended falls apart.

But “The Cold Equations” is not unbelievable.

Most objections are either explicitly dealt with in the first few pages, or can be inferred with minimal scientific knowledge and common sense.

- there’s no margin of error for fuel (and no copilot/autopilot) because it’s an emergency rescue vehicle. This, not this.

- such incidents are described as incredibly rare (“Perhaps once in his lifetime an EDS pilot would find such a stowaway on his ship”). This is why security is lax: Little effort is spent preventing once-in-a-lifetime events. When you arrive at an airport, does a security guard shake you down and yell “do not – and I mean NOT – put wasps inside the plane’s pitot tube!“

- unbolting the chair means he dies while braking. It is likely a deceleration couch.

- he can’t cut off her legs (or his), he has no tools, training, etc.

“The girl’s stupid!” Perhaps. “The company is evil!” Perhaps.

Are either of those things unrealistic?

In a perfect world, the scenario would not occur at all. The rescue vehicle would have more fuel, a preflight check would be done, etc. But stories have no burden to present a perfect world. They aren’t pornography or junk food: they have purposes beyond making people delusively happy. The reason “The Cold Equation” punches so hard is that it echoes the world that really exists.

“The girl dies! And that’s sad/unfair/sexist!”

For example, Cory Doctorow’s argument with a pussyhat and an #ImWithHer badge.

I always hated the story The Cold Equations even though it’ll make me cry every time, because of the weird implicit chauvinism. Space, after all, is for hardened men who’ll do what must be done, and not for silly girls with all their emotions. It’s yet another narrative in which a woman is punished for straying beyond her domestic sphere […] When the woman transgresses, she must be punished – not out of cruelty, but simply because that is the logical thing to do, the only way for continued survival. […] he chose to write his story so that a woman’s death is the Rational, Right decision.

Feminist critiques seem to focus on the woman-dying angle. They parse the story like a robot programmed to conduct basic formal logic. Woman dies in story -> women dying is bad -> story is bad.

First, let me state the obvious: the girl does not exist. She is made up.

She is a fictional character who never had a life. It is a waste of time mourning her fate, or writing “fixed” versions of the tale where the girl lives. You are rescuing a nonexistent person.

She is written as a recepticle for audience sympathy. That’s her role in the story, just as the pilot’s role is to decide her fate, Commander Delhart’s role is to confirm the bad news, the sick people’s role is to be a McGuffin, the brother’s role is to be another McGuffin, etc. They are all plot elements, puppets dancing to the author’s will. None of them possess any personhood.

This topic really frustrates me: people treat the details of fictional worlds as though they matter in and of themselves, instead of merely being tools for the artist to express ideas. Hamlet is about a Danish prince, but the same story could have been told about a Mishraqi sumac farmer. The details are arbitrary and disposable – by overfocusing on them (“if the Professor on Gilligan’s Island is smart enough to build a bamboo lie detector, why can’t he fix the hole in the boat?”), you lose what matters: theme, subtext, epiphany.

“The Cold Equations” is actually not about a girl dying, any more than Hamlet is about a Danish prince. It’s about taking the implicit trolley problems that exist unseen all around us (do you have $2300 USD in the bank? Why are you allowing a child to die?) and making them explicit. Saving the girl would have gutted the story. Campbell did not expel her from the airlock because he thought it was funny or hated women, but so the story would hit emotinal paydirt.

From the Aimee Ogden story linked above:

If a man at a desk can kill a girl with a little bit of ink, then we can save her in exactly the same way. There are more of us than there are of him. Break his pen, throw it out the window, and send the desk after it.

Yes, the girl could have been saved with a little bit of ink! It’s so easy!

Just as James Cameron could have saved the passengers of the Titanic by changing the iceberg to sunshine and rainbows. And Art Spiegelman could have saved all the Jews in Maus by changing Auschwitz into an amusement park.

So why didn’t they do it, then?

Because it would have destroyed the artistic content of their story, duh! How is this not obvious? The theme is the important part of any story. Not the details, which are made up, in any case. From inside “The Cold Equations”, a girl can die, or seven people can die. From the outside, a girl can die, or the story can die.

Campbell, like the pilot, chose correctly.

“It’s bad engineering! No sensibly designed system would allow this to occur!”

This is the last and worst argument.

Here’s my response, in meme form.

I wish I could meet these people, who apparently think engineering failures and badly-designed systems are implausible fairytales, as unlikely as Bigfoot. Life must be nice on their alien planet.

It’s a planet where a Boeing 767 didn’t run out of fuel in mid-air because the crew had calculated their last refuel using pounds instead of kilograms, where a $327.6 million space probe didn’t incinerate itself in the Martian atmosphere because the software mixed up metric and imperial units, where the Banqiao Dam didn’t collapse and wipe out 5 million houses due to a missed telegraph, the Chernobyl No 4 reactor didn’t melt down due to confusingly-written operating instructions, the Hindenburg didn’t explode due to some surely easily fixable thing, the Challenge Space Shuttle didn’t explode because of a frozen rubber O-ring, 30 million homes in Ontario didn’t lose power due to to one tripped relay, 210 million gallons of oil didn’t flow into the Gulf of Mexico due to a faulty blowout preventer, a surveyer’s mistake didn’t cause the US government to build a large fortress on the Canadian side of the border, there are no $220 million fighter jets being brought down by geese (to be clear, “geese” does not mean some fancy guided missile, “goose” means those birds you eat for Christmas dinner) etc, etc, etc.

Again, it should be remembered that the story describes an extremely rare occurrence. A black swan event. Hard to be prepared against something that doesn’t happen often.

I remain confused about what the readership of science fiction today expects or wants. “The Cold Equations” is imperfect, but most of its critics seem functionally illiterate: focusing on things they shouldn’t focus on, asking questions they shouldn’t ask, scrutinizing it on a level it was never written on.

They’re actually worse than illiterate: an Andamanese tribesman wouldn’t understand the story, but at least he wouldn’t get it precisely backward.

The girl’s intelligence is frequently questioned, but when the pilot explained her fate, she accepted it. Most of her critics would have kept repeating “well, that can’t happen! Spacecraft are engineered with fault tolerances! Also, have you considered that women dying is sexist.” until the pilot reached for the DEPRESSURIZE button.

No Comments »

A consequence of modern technology is that you can make very detailed worlds blink in and out of existence by sliding a fader. Enter a number for a noise threshold. Black. Enter a different number. A universe of life pullulates on the screen, florid, dense, intricate as a dendriform fractal. Enter a third, the universe goes dark again. The awe of easily creating something from nothing is cancelled by the fact that your creation can be consigned to the nonexistence with equal ease. Does changing a variable and creating a city that advance the reality of that variable, or remove the reality of that city?

The trick is that technological representations of the world don’t capture the full spectrum of what’s going on. Much like biological senses (heard any good frequencies at 22kHz lately?), they only give us part of the world. A selectively-chosen slice.

Without such filtering, our surroundings would be literally incomprehensible. A meteorologist doesn’t need or want to know the position and angular velocity of every single air molecule on the ground. That would just choke the system with noise, and make eyeball-level analysis of the data impossible. So he views simplified versions of the wind and rain, with the movement of cloudfronts simplified to just a few vectors. This means missing out on fine-grained local scenarios, but that’s fine, so long as he possesses the big picture.

But sometimes the big picture is enclosed within the small picture.

In the late 2000s, drone warfare saw a doctrinal change. Where drones had once been used to eliminate targets in moving cars, now they were striking buildings in dense city centers.

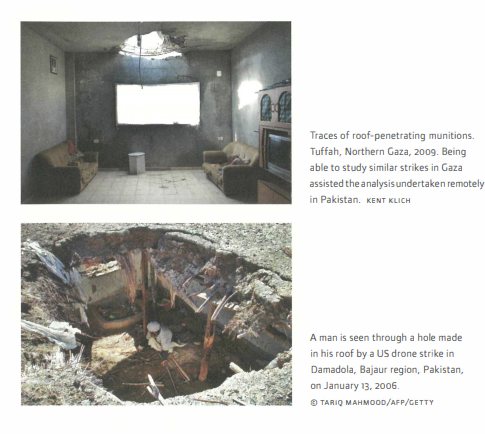

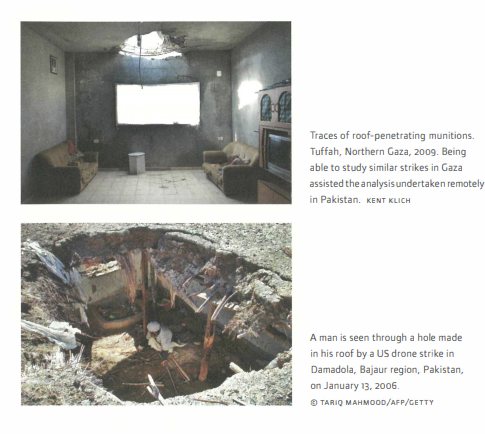

Basically, a missile striking a car leaves a pile of flaming wreckage. It’s visible to everyone. A missile hitting a building will punch a small hole through the roof, and explode inside the building, out of sight. Both will kill, but only one of them makes a mess visible from the air.

This change wasn’t prompted only by tactical concerns, but by propaganda. Coalition forceswanted to fight terrorism in a silent, photogenic way, without giving their enemies PR victories. The mid 2000s saw a dismal march of videos and footage that you can probably remember and name – Abu Ghraib, Collateral Murder, and so forth. The military would prefer that these incidents no longer happen. By incidents, I don’t mean the events themselves. I mean the fact that they were photograph and reached the media.

Millions of dollars are spent designing weapons that don’t look like they’re doing what they’re doing. The “Romeo” Hellfire II or AGM-114R was developed in 2009 and saw mass production in 2012. It features a special charge and delay fuse that adds a few milliseconds between impact and detonation. This allows the Hellfire II to pierce multiple layers of brick, adobe, and concrete before exploding. The fireball happens on the bottom floor, far out of view from the sky.

Remember that drones are used because they are perceived as more “humane” than traditional alternatives. Those who are caught inside their fury – a hailstorm of fragmented steel that shreds flesh from bone – would disagree, but the reality is that the US military would doing something worse if they didn’t exist. Drone strikes are saving lives, when you think about it. It’s cruel to not drone people.

The Hellfire II is used in places where journalists and human rights investigators can’t go. You can’t get reporters on the ground, seeing the fruits of the explosion. The only way to obtain images is from satellite photography.

Photography literally means painting or drawing with light. Digital photographs net the light. They render the infinitely complex detail on a grid of pixels. If an object is smaller than a pixel (and below a threshold for interpolation), it literally disappears. It’s a net, as a fisherman would cast. If the grid is too fine, it trawls up waste and uselessly small fish, eventually choking on its catch. Too big, and you let fish escape.

Satellites, far above the earth, fish for light with a rather loose net. In the 70s, Landsat earth-observation satellites recorded data at 60m/pixel.

At this resolution, the human race barely exists. 99% of our works disappear. Only the largest buildings are 60m long. A single pixel might contain an entire town, lurking unseen.

In the 80s and 90s, satellites refined the resolution to 30m/pixel and 20m/pixel. This is the moment where civilization begins to slide into visiblity. A chemical leak, large explosion, or mass grave might should be visible on a photograph.

This might be the point where it stops. Limitations of technology aside, we’re now the scale human bodies can be seen: a fraught ethical bridge to cross. Surely people have the right to not be watched by a sky-spanning satellite panopticon when they step out of doors. For years, publically-released photographs were legally not allowed to crop closer than this limit.

And as luck would have it, the Hellfire II makes a hole in buildings smaller than 0.5m/pixel – so these strikes technically do not exist, insofar as publically available satellite photography is concerned.

Gutted buildings. Shadows of men flash-burned into walls. All of it, disappeared. Technology does not only enhance our vision, it also degrades our vision, effectively disappearing war, combat, and geopolitical crime.

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism (BIJ) tracked 380 strikes in Pakistan from 2004 to 2014. 62 percent (or 234 incidents) were targeted at domestic buildings. These drone missiles resulted in as many as 1614 civilian casualties in Pakistan alone. But they no longer exist.

Wherefore art thou Romeo?

No Comments »