A great book. The best Dark Tower novel? Yes. The best Stephen King novel? Possibly. It has one of his best lines, anyway.

He thought: Very well. I am now a man with no food, with two less fingers and one less toe than I was born with; I am a gunslinger with shells which may not fire; I am sickening from a monster’s bite and have no medicine; I have a day’s water if I’m lucky; I may be able to walk perhaps a dozen miles if I press myself to the last extremity. I am, in short, a man on the edge of everything.

I don’t want to think or write about The Drawing of the Three: I want to re-read it. It’s coked-up and manic, bouncing off the walls like a kid in a small room. The plot moves unbelievably fast – only The Running Man is paced faster, and not by much. It’s ludicrously overstuffed with thrills: later Dark Towers can have a cosy, rambling feel; here the tension drawn so tight that each line seems ready to snap. You can almost cut your finger on the flat side of the page.

It picks up the tale from where The Gunslinger ended it: Roland (the last guardian in a dead or dying world modeled on our romantic image of the Wild West) has just damned his own soul in his quest for the mythic Dark Tower. Alone and friendless, he collapses from exhaustion on a beach, and is attacked (and mutilated) by a monster from the waves. Soon he’s becoming desperately and incurably sick – either his wound is infected, or the monster was venomous. He realizes that he might die before he ever finds the Tower, and attempts a series of “drawings” – rituals bringing other gunslingers (or equivalent gunslingers) from other universes into his world. He hopes they’ll either save his life or fulfill his quest for the Tower after he dies. All he knows about these supposed allies is a shred of biography. There’s a man in thrall of a demon (unknown to Roland) called “Heroin”, a woman who appears to have a split Jekyll-and-Hyde personality, and the personification of death itself.

Roland proves to be just as strong an anti-hero as he was in the book before. The drawings are little more than abductions. He will not take no for an answer, and he has no intention of allowing the proto-gunslingers (who, as chance would have it, all live in 20th century New York) to leave. He has good reasons for doing this – he believes the Tower will soon fall, spelling the end for the last pitiful dregs of creation, unless someone saves it. But it makes him as dark as the tower he’s chasing, and turns him into Clint Eastwood’s Angel Eyes, as menacing as he is heroic.

The Drawing of the Three isn’t perfect. The first third of the book spends a lot of time in Miami Vice territory, featuring cocaine smuggling and DEA agents and cartoonish gangster types: it’s fun but runs a little long. Eddie Dean’s backstory is also overdeveloped considering how uninteresting it turns out to be. The book also features a serial-killer yuppie character that seems ripped off from American Psycho (it’s not – The Drawing of the Three was published four years earlier): a great idea that King could have done more with. Detta Walker proves herself the book’s most inspired villain by the end, not Jack Mort.

But there are far more things that work. Huge swathes of the book are just “a guy walking alongside a beach”. Instead of dead zones in the plot, these become fraught with tension thanks to the ticking clock of Roland’s sickness (which also allow King to explore Roland’s backstory through fevered hallucinations of life before the world apocalyptically “moved on”). Roland was an almost unbelievably good gunfighter in the first book, effortlessly gunning down dozens of people, so King makes the few shootouts interesting by giving him unreliable ammunition (Roland unwisely allowed his shells to become wet by sleeping in wet sand, and many of the bullets he chambers in his revolvers misfire). This is great, effective storytelling, killing lots of birds with very few stones.

And there are hilarious moments too, particularly the parts where Roland (a man from another world who is as much an Arthurian knight as he is The Man With No Name): has to interact with foul-mouthed New Yorkers. This was a big part of what sunk the later books for me: it killed the atmosphere of King’s Lovecraftian Western “Mid-World” to have characters name-dropping Hollywood movies and baseball teams every few pages. But here, the lightness serves a purpose, cutting the dread to manageable levels, like the baby powder in Eddie’s heroin.

‘Well,’ Eddie said, ‘what was behind Door Number One wasn’t so hot, and what was behind Door Number Two was even worse, so now, instead of quitting like sane people, we’re going to go right on ahead and check out Door Number Three. The way things have been going, I think it’s likely to be something like Godzilla or Ghidra the Three-Headed Monster, but I’m an optimist. I’m still hoping for the stainless steel cookware.”

The Dark Tower, at its core, was King’s merging a Lord of the Rings-type epic fantasy quest with genre conceits of a Leone/Sturges/Peckinpah Western. The concept went off the rails for various reasons worth explaining at length, but it’s interesting that the best book in the series had the least time for leather-slapping cowboy cliches. The Drawing of the Three has no cattle rustlers, no dusty red canyons, no bars with batwing doors, one Mexican standoff, certainly no war-whooping Injuns or sniggering bandidos. Instead it’s a fantasy-horror story of a man and his magic, going to other worlds.

King often does his best work with very sparse plots. I’ve heard it said that videogames work not by letting you do things but by not letting you do things (Super Mario Bros would be no fun if Mario could fly, for example), and King has a similar property: he gains strength under restrictions. You can tell the story of Misery, Gerald’s Game, The Shining, in a single, reasonably short sentence. But just as very good sketches can suggest more detail than a photorealistic drawing, King’s threadbare stories never fail to gain largeness and life.

No Comments »

There’s a British TV figure known for his performances of a pirate, a transvestite, a mass of sentient toxic sludge, a roided-up penguin, a horned devil, and an evil clown. But enough about Boris Johnson, let’s talk about Tim Curry.

David Bowie was a musician who dabbled in acting. Curry was the opposite: an actor with aspirations of rock stardom. But where Bowie’s film appearances are (overall) remembered fondly, Curry’s albums are barely remembered at all. His failure to “break out” as a rock frontman in the late 70s evidently galled him, as seen in interviews like this one, where he takes shreds out of a journalist for asking him about Rocky Horror Picture Show (“I think that it is one of the most boring journalistic openings that I have ever heard”). These albums are sad to experience as a Curry fan: listen to them and unfulfilled dreams float past.

Regrettably, the same is not true for good music. 1979’s Fearless has one outstanding moment: “I Do The Rock” lives up to its title, shameless and vulgar and full of panto swagger. You’ve never heard “rawwwhhhkk” pronounced the way Tim Curry pronounces “rawwwhhhkk”. Album closer “Charge It” is less memorable but at least has a pulse. These two songs could have made it onto a good Lou Reed album, unlike the others, which would more or less make weight on a shitty Lou Reed album.

The songwriting is a flat line: boneheaded rockers like “Right on the Money” and “Hide This Face” sound written by hacks-for-hire from the bottom tranche of A&M’s songwriting division (dismayingly, they were written by Curry himself). Robotic performances with no dynamics means Curry has to salvage them with the force of his personality, and although he has charisma and a good voice, he doesn’t understand “singing” that well: often his vocal work devolves into shouted theatrical tirades over repetitive musical motifs. It’s amusing for a few songs, less so for a full album.

“Paradise Garage” is a would-be disco song with a Bee Gees bassline buried beneath a tacky wall of guitars and Curry (apparently) making up lyrics on the spot in the recording booth. It has all the club potential of Little Jimmy Osmond. “Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire” is a cover of Joni Mitchell, a woman who has dubious right to oxygen, let alone covers.

Curry needed better songs, but even if he’d had them, where does a man like him fit in Thatcher’s Britain? The most relevant cultural moment (campy, wig-snatching glam rock) had passed five years earlier – Queen aside, 1979 was year of Blondie, ABBA, and The Police. Soon Bowie and Boy George would almost be issuing public bulletins declaring that they weren’t gay. Fearless is an interesting curio from a straightlaced time, but little more. Not worth getting for one great song.

I almost forgot to tell you about the power ballad “SOS”. I have a suggestion, though. Burn a copy of Fearless, but skip over track 4. Got it? Your new copy should go straight from “I Do The Rock” to “Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire”. Now take the original CD and drive it to an empty field somewhere. A place where no bystanders would be hurt if six megatons of thermobaric ordnance were to strike the ground, if you catch my meaning.

Then, contact the CDC, the FBI, the DHS, the MI6, every alphabet agency your country has. Tell them the CD contains anthrax, national secrets, fascism, child porn, and systemic racism. Yes, all of those things at once. Say that the anthrax spores are arranged in the shape of a naked eight-year-old child-of-color being molested by a government agent who’s sig heiling with one hand and downgrading the child’s future credit score with the other. Then retreat to a safe distance, strap on heavy-duty protective goggles, and watch the world become a better place.

No Comments »

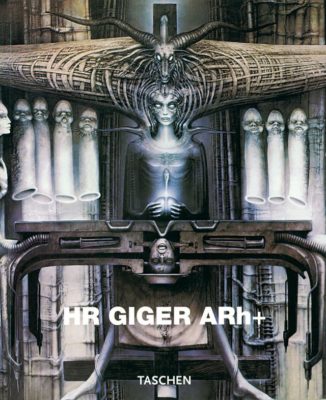

This Taschen artbook explores the work of Hans-Ruedi Giger, who died not long ago. It’s fairly large (23cm*30cm), the print quality is fine, the binding in my copy was falling apart, and Timothy Leary’s foreword is scarier than the actual book. “[Giger] has obviously activated circuits of his brain that govern the unicellular politics within our bodies, our botanical technologies, our aminoacid machines” etc. Yikes.

Why Giger? He was special. Like Hieronymous Bosch, William Blake, and Junji Ito, he saw worlds that nobody else could see. He worked in a lot of mediums but is most famous for his airbrushed “biomechanicals”: totemic, terrifying creatures with dripping teeth, corrugated hides, and electrophosphorescent eyes. They’re an impossible mixture of life and not-life, future and past, sterility and dirt; ancient Egyptian gods built on a Soviet assembly line. There’s little else like them: no artist has ever copied Giger’s signature style with much fidelity. You might say that biomechanicals are more commonly found in reality than in art.

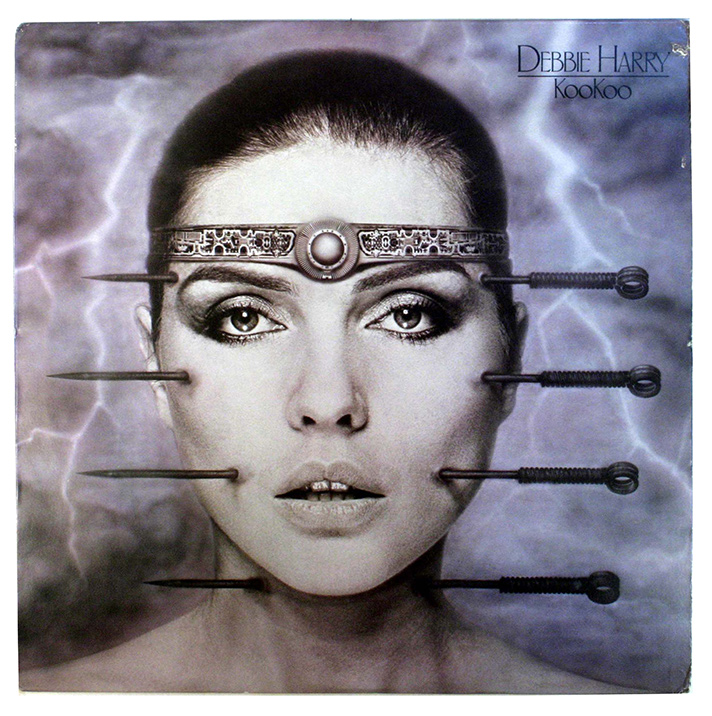

Despite some avant-garde leanings, he was a commercial artist through and through – even after “Giger-mania” took hold in the 70s he wasn’t above decorating heavy metal sleeves, or PC game box art, or guitars, or mic stands, or lager bars. His art showed you unexpected things, and could also be found in unexpected places.

Metal was one of Giger’s favorite subjects. So was flesh, and the ways one can be enhanced or diminished by the other. In the typical Giger image pipes coil and mutate, becoming snakes and phalluses, and glistening shafts and struts pierce necrotic blue-black skin. Giger didn’t predict the future. He grew up in an age of titanium hips, electrical pacemakers, and so on: men have altered their bodies through mechanical means for a long time. Giger’s insight was to tease out the aesthetic power of this union. His creepy-crawly arc-welds of the biologic to the anodic are overwhelming and hit the eye like a bomb. They’re almost too ugly to look at. Or too beautiful. His greatest works actually manage to be both at the same time.

But there’s no sense of gore or mutilation to Giger’s art. He weaves metal through soft tissue and keratin and bone in a way that looks natural, as though evolution rather than surgery produced his creatures. There’s also no motion: Giger’s art has a stillness that’s striking: the “biomechanics” don’t even seem capable of movement. The creature he designed for Ridley Scott’s Alien became a horror movie monster that scampers and leaps around, but there’s none of that in his original artwork, no impression that it might be ready to impale a blood funnel into your chest. It looks petrified in place, a stone god of a stone universe. An advantage of fantasy is that you can create a world that plays to your strengths as an artist, and though Giger never had much talent for evoking movement, he could imagine a place were movement doesn’t happen. His creations are like heavy machines in a factory: bolted into the floor and never moved again. They look perfectly at ease within the environments he creates for them.

The autobiographical text – written by Giger – proves less interesting than the pictures. He doesn’t want to talk about himself, which I submit is a disadvantage when writing an autobiography. He grew up in 1940s Graubünden, lived a childhood so uneventful it’s a miracle he didn’t perish from boredom, worked in advertising, and so on. His father wanted him to become a pharmacist, but he had a dream, maaan. Giger focuses on the dullest details possible, and we never really understand what formed him as an artist. This continues in later passages, where he relates his rise to fame (which reached its peak in 1979, when Alien won him an Oscar for Best Achievement in Visual Effects). Occasionally there are oblique suggestions of personal trouble. “…after the PR commotion and stress”…what stress? “My inner despondency…” What despondency? Giger’s biography fails a basic test: it’s less vivid and informative than reading his own Wikipedia article.

I know someone who attended a Pink Floyd exhibit in Milan – one clearly curated by Roger Waters or someone, because it whitewashed away any controversy, reimagining Pink Floyd as a band of great mates who got on a treat and made awesome music together. The problem (aside from dishonesty) is that the Pink Floyd story is incomprehensible if you don’t talk about the bad stuff – Syd’s mental collapse, Waters’ disillusionment, the destructive infighting. A naif would be left standing underneath a huge sign saying “PINK FLOYD IS BACK!” and wondering “where did they go? And why are there now three people in the band photo instead of four?” Giger’s account of his own life was is a little like that. Things were clearly being left unsaid, which is a shame. I suppose the pictures are the important thing, but they needn’t be the only thing.

The Giger style lives on after him, even though he’s the only one who could really do it. Otherwordly or alien is a common adjective used to describe it, but it’s a specific cold-blooded alien aesthetic. I used to read popular astronomy books which would talk about how moons such as Europa and Enceladus might have liquid oceans, and there would always be the suggestion that we might find fish living there. This is unlikely: life requires a source of free energy, and there’s almost none in such systems. If anything did live, it would be very slow, very conservative of motion. It might communicate and reproduce through radio photons. It would shift fractions of an inch per millenia. If it could think, it would regard motion the way we regard time travel – as an absurd theoretical conceit.

In other words, they might look like HR Giger’s half-frozen monsters. Very cold. Very old. Shunning movement. Giger was the god of the formaldehyde-filled vein, the unbeating stone heart, the liquid nitrogen-cooled brain, and this book cryo-preserves a lot of his unique genius.

No Comments »