In ’42, German forces advanced into Russia in the depths of winter. They were confident, thinking their foes weak and in retreat. They were about to be destroyed.

This was 1242, when a young Russian prince lured an army of Teutonic knights and Estonian auxiliaries onto the frozen surface of Lake Peipus and slaughtered them on the ice. Alexander Nevsky’s victory is remembered in Russia as Ледовое Побоище, or Icy Massacre, and might be history’s only naval battle to not involve a single boat. It ended the Teutonic Order’s pretensions upon Novgorodian territory and turned Nevsky into a national hero, sainted in 1547.

Heroes never die. Even when they pass away, something of their essence remains in the national heartwood, inspiring others through the centuries. Seven centuries after Nevsky died, history began to loop back on itself. A prisoner in Germany wrote a book about the future. He was ambitious; mad. He wanted Europe in flames, and a German empire atop the bones of a Russian one. Eight years later that man was both free from prison and Chancellor of Germany. Armies were gathering, and Russia needed heroes once again.

It was inevitable that a film about Alexander Nevsky’s life would be made: a Russian patriot fighting German Catholics was a perfect propaganda coup. Also, Nevsky had died a very long time ago, and we don’t know much about him as a person. This allowed a director freedom to “interpret” him as whoever they wanted, as well as freeing him from troublesome contemporary politics (unlike the Russian generals who had fought Napoleon…on the side of the tsar).

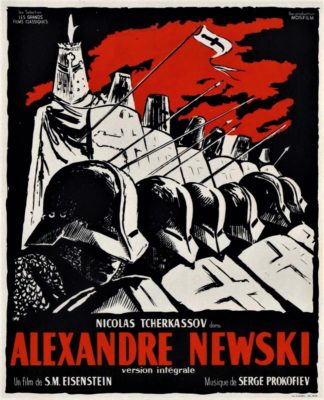

Alexander Nevski was directed by Sergei Eisenstein, with many asterisks and scare-quotes around “directed”. Soviet culture regarded artists as civil servants; if you could write a poem or paint a picture you were expected to do so for the state (and under the state’s supervision). Eisenstein was regarded as suspect when he made the film: he’d spent years living in the west, only returning after what appears to be blackmail. His previous film Bezhin Meadow had failed and earned him a public reprimand. His friends were being arrested, and he soon suspected that the NKVD was shadowing him. Eisenstein probably saw Alexander Nevsky as his last chance, and resolved not to put a single foot wrong. It’s debatable to what extent it’s “his” movie.

It was filmed in 1938 and produced by Mosfilm, with the final cut receiving some additional tinkering by the Party. You could almost give Joseph Stalin an editing and production credit. The picture gained final approval from the State Committee for Cinematography and was released on December 1938, although it hit a snag when when the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact turned Russia and Germany into momentary allies. Ultimately it was a success, rescuing Eisenstein’s reputation and gaining him a new following abroad. It’s a huge, huge film. Irrefutably part of the canon.

But is it good? Difficult question. As journalist Chet Flippo said after seeing a Queen concert, it “got the job done. I’m just not sure what the job is.”

As a movie it’s a disappointment, featuring rancid acting, a dull story, and sententious touches (medieval Teutons that wear swastikas) that turn its historical setting into chopped liver.

It’s a relic from a bygone age when film was theater’s little brother: get ready for ponderous cinematography, pounding melodrama, shouty brow-furrowing performances, and a total lack of subtlety. Your enjoyment of Alexander Nevski depends on whether you think shots like this are dramatic or silly.

Nevsky is played by Nikolay Cherkasov, whose impression of a wooden board is second to none. His acting skills are suffocated by the role he’s playing: he’s Alexander Nevsky, Great Hero of the Motherland. He doesn’t have a love interest because his love is Russia, he can’t show weakness because Russia has no weaknesses, he can’t fart because that would be like Russia itself farting, etc…

Sergei Prokofiev’s score is acclaimed but I didn’t enjoy it: its shifts from movement to movement (with wildly different moods) sound weird and inorganic next to modern film scores. It’s probably great. I just can’t find a way into it. The subtitled dialog contains deathless Yoda-esque lines such as “They are strong! Hard will it be to fight them!” that hopefully flow better in the original Russian.

Eisenstein (as noted by Roger Ebert) sometimes made films that ascended directly to “great” without actually being good. Alexander Nevsky feels like that sort of movie: it has a spot on the film school curriculum but maybe not in the hearts of many students. It’s a 50 foot colossus with a clown shoes and a big red nose. Huge, important, towering above the landscape…but at the same time, it’s hard to take seriously.

In short, it’s a film of its time. In nearly every scene, shot, and frame, there’s something that jolts me out of the picture. The film at its best is a 1930s version of James Cameron’s Titanic, lavish and expensive, carrying the heft of history, with some innovative and somewhat impressive filmmaking techniques all built around a massive effects-driven set piece. At its worst, it’s patently absurd and laughable.

That’s one way of looking at Alexander Nevsky. The other is as a source of patriotic hope.

The darkness in the West hangs over all of this. You have to remember the circumstances of its production, who would have wanted to see it, and why. Many of Alexander Nevsky’s apparent flaws disappear when you watch it the way you’d listen to a national anthem as a patriot, or attend a church service as a believer.

The broad characterization and black-and-white morality are like anchors, points of stability in an unstable world. The Teutonic Knights are vile (there’s a horrible scene involving infants being thrown into a fire), but so were the real life Nazis. The film runs highlighter over Russian pride and German evil, relating everything back to the USSR’s contemporary circumstances. The historical garb is thinner than rice paper. I don’t think it was meant to be judged as a movie.

Even the film’s camp moments are interesting. At the start we see a Mongol chieftain offering Nevsky a command position in the Golden Horde (which is declined). He’s a silly fat man with a top-knot that looks like Mickey Mouse’s ears.

I am no expert, but I can’t find a photo of a traditional Mongolian (or Chinese) hairstyle that looks like that. It seems unique to the film. I half suspect we’re supposed to think of Mickey Mouse’s ears – the black cap contrasting with his pale skin completes the image. Mickey Mouse (like Alexander Nevski) is inseparable from one particular country: the United States.

Does the Mongol Mouse represent capitalist America in the film? Just as Nevsky represents Russia? That would explain the ominous dialog where Nevski says that although the Mongols are a threat, the Germans are worse and must be fought first. “The Mongols can wait, methinks. We face more dangerous foes.” The difference, Nevsky goes on to explain, is that Mongols are greedy and can be placated with gifts (like capitalists), while the Germans are evil, destroying all that isn’t them (fascists). This anti-fascist angle, it must be said, now looks odd in light of how the Mongols are depicted as grubby savages, while Cherkasov is a tall, blond Aryan superman.

The rest of the film features more blatant pro-Soviet propaganda. Nevsky butts heads with with wealthy boyars (representing kulaks) and priests (representing…) who don’t understand the danger, want to appease the enemy, etc. Fortunately, Nevsky has the people on his side.

This isn’t even pseudo-history, it’s fan-fiction, like a teenage girl making Harry and Draco kiss. The real Alexander Nevsky was a rich aristocrat who took monastic vows. He wasn’t any kind of rabble-rousing working class hero (let alone an anti-capitalist or anti-clericalist). This is Russia’s 1930s political milieu projected seven hundred years into the past. But this is like noticing that Americans depict Jesus as white: it misses the point. Alexander Nevsky isn’t supposed to depict history except in a superficial way. It’s doing something more elemental, issuing marching orders to a nation.

What about the battle scene?

The final third of the movie is eaten up by an extremely long battle involving elaborate staging and hundreds of extras. The rest of the movie seems draped across this set-piece like a threadbare set of clothes (again, Titanic). When the horns blare and the massed columns of infantry advance onto the ice, you forget about everything that happened before. It’s its own self-contained universe.

The scene is groundbreaking – literally groundbreaking, it ends with an army falling through Lake Peipus – and ranks among the most thrilling moments yet seen in a movie. How did it take just forty years to go from Fred Ott’s Sneeze to this? Even today, the battle looks fairly good. Almost any time you see a motion picture featuring a cavalry charge – be it Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings, Mel Gibson’s Braveheart, or Sergey Bondarchuk’s Waterloo – it’s trying to look like Alexander Nevsky, consciously or otherwise.

Yes, you can sort of tell that the actors are being filmed under a bright sun on a hot day, but in black and white it’s not obvious. Films have something called “day for night” (a “night scene” that’s clearly not at night). Alexander Nevski went one further: hot for cold. Sand is used in place of snow. Huge sheets of broken glass are used in place of ice. The incredible thing is that it works.

It must have taken a staggering amount of money to film the battle. The costumes, props, and so forth look perfect, and there are hundreds of them. Within a few years, Russians would be facing the Germans with empty rifles, tanks without radios, etc. There’s a grim irony to the fact that (based on the opening weeks of Operation Barbarossa) the USSR was better at fighting a fake war than a real one.

It has some dated elements. Eisenstein wasn’t able to capture the violence and kinematics of an actual battle. Blows are half-hearted. People fall over dead for no reason. Horses are perfectly calm where they should be white eyed, terrified, and spraying foam.

This moment made me laugh. It was like a Keystone Kops gag.

The sheer length of the battle wore me down. Just shot after endless shot of men swinging swords at enemies conspicuously out of frame. I’ll admit that after twenty minutes of this, I wasn’t overjoyed by the prospect of twenty more.

However, the battle ends on an striking visual: the beleaguered Germans collapse the ice with their weight and drown. This is apparently fiction – no contemporary accounts describe such an event – but it’s good, effective filmmaking, breaking the tedium of the battle and providing effective closure to the ice scene. It’s Chekov’s gun in the end. Put a gun on the set, and it has to get used. Put an army on a a frozen lake, and they have to fall through.

Many nations have legends of sleeping champions (Portugal’s King Sebastian, Britain’s King Arthur, Germany’s Frederick Barbarossa) who will return to fight for their homeland in its hour of need. But the atheistic USSR didn’t believe in such fairytales. They forced Nevsky back to life, through the magic of cinema. They probably thought they had to.

It’s a little hard to recommend the entire movie, although the battle is worth watching. Alexander Nevsky does not escape the time its in. You have to take it for what it is, a propaganda tool for a desperate nation facing desperate times. Seen with this in mind, it has a chilling power. Thunderclouds seem to hang above it. Walls of tanks clank in the background. Ahead lay a nightmare: a war so awful that historians disagree not just on how many Russians died, but how many million. The battle is inseparable from the mechanical savagery of Stalingrad and Kursk. The burning children reminds of the Holocaust.

Few films gain so much from their context, and few films have a context this awful. Alexander Nevsky is like a battle standard overlooking a battlefield. It’s just a crude image of a lion, fluttering in the wind. But underneath that lion are rivers of gore, shattered bones, smashed helmets and vambraces, cries of the wounded, and feasting crows.

No Comments »

On March 1954 the annual edition of The Great Soviet Encyclopedia was published by Moscow’s Sovetskaya Entsiklopediya. Under B was a glowing article on BERIA, LAVRENTIY, the great hero.

When Beria was denounced as a spy, tried, and executed later that year, The Encyclopedia’s subscribers received a letter asking them to cut out and return his page. They were sent a replacement article (this one on the BERING STRAIT) which they were to insert into the volume so there’d be no missing page, no jump of numbers, no indication that a change had been made. Beria had been annihilated: cut from history, and the cuts also removed.

In the Soviet Union it was easy to unexist at any time and for any reason. It didn’t matter who you were: a decorated war hero, an inner party member, a useless artist, Stalin’s own daughter. Nobody was safe, nobody was above suspicion. The Soviet Union did scary things to be people, far more unsettling than mangled bodies in a ditch. Execution takes away a future: the USSR tried to take away everything.

By 1952, Soviet historical revisionism was becoming common knowledge. In Foreign Affairs Vol. 31, No. 1, journalist and ex-communist Bertram David “Bert” Wolfe laid out the case for this in embarrassing detail: they weren’t particularly subtle or worried about being caught. Important historical figures weren’t present in the USSR’s textbooks, facts were retooled and adjusted to fit narratives, and in some cases, entire races of people seemingly vanished.

Stalin warps history into a Procrustean bed of his own design […] Deletions from, and insertions into, the original texts of Lenin’s Collected Works as well as his own. The object in this method is to establish his infallibility during and after the October Revolution. […] expunging of the name of Trotsky from all available records. […] Omar Khayyam ceases to be a Persian poet of Nishipur and becomes “a natural product of the Tadzhik people” (a Soviet Republic). Shamil is no longer to be remembered as a hero of the Caucasus who led his people in resisting Tsarist oppression; he is now a “reactionary serving the interests of Britain and Turkey” more than a century ago. […] Companions of Lenin who opposed Stalin became unpersons — their names erased from the scrolls. Nationalities suspected of disloyalty in war, such as the Volga Germans and the Crimean Tartars, became unpeople, — their identities evaporated, and their peoples scattered through the steppes. Material things which offended him, such as museums devoted to native arts instead of to Great Russian benefices, became unobjects, — their contents marked for the trash can. […] When Stalin changes his line or attitude (toward anything under the sun, past or present) the historians must push the new concept backward to include all that went before. The present enemy must be viewed as having been the enemy always. Books, articles, statements, and so on to the contrary, must be purified or burnt. […] To quote the 1934 Stalin in Russia 1952 would be to take one’s life into one’s hands.

Wolfe describes this red-pen attack on reality as “Operation Palimpsest”, which is an odd way of putting it. Palimpsests are old pieces of parchment where the writing has been scraped away so that another layer of text can be overwritten (literally) in its place. In the 21st century, with the aid of chemicals and spectral analysis, we can usually recover the original text. Palimpsests, in other words, are failed acts of removal. The writing is hidden…and yet it remains.

In other words, just like Stalin’s censorship.

As the Beria story illustrates, you can’t just hide something, you also have to hide the act of hiding. It’s no good for a magician to make a rabbit vanish if the audience can see the pulley and wires and trap-door. Political history is replete with examples (Watergate, Lewinski) of bungled coverups that probably did more harm than the original crime, and poorly-done censorship can draw attention to the very thing it tries to cover up.

Below is an infamous pair of photos, synonymous with Orwellian creepiness. They half-depict Nikolai Yezhov (Stalin’s NKVD head from 1936-1938) before and after a history adjustment.

Is it a good fake? I don’t think so. The framing gives it away. No photographer would compose a shot this way: with the subjects packed onto the left and the right showing just empty water. Clearly there’s supposed to be someone on Stalin’s right.

This picture would pass casual inspection, but if you knew that government photographs were prone to censorship, this one would raise red flags (in many senses). Nikolai Yezhov is gone, yet he’s more present than he was before. It’s a method of censorship that reverse-censors, like hiding something beneath a spotlight.

Even if the editor had cropped the photo tighter, it’s possible in theory that Yezhov’s presence could be re-established by a sufficiently advanced machine learning algorithm. We’ve been teaching computers to read emotions from contextual clues since 2003. Perhaps the reverse can happen – an AI reconstructing context from an emotional state. Perhaps there’s something subtle about Stalin’s expression or posture that indicates there’s a man on his right. I’m not sure if it’s possible, but we’re absolutely getting closer to a world where it’s possible.

Technology is the specter at the feast. What will it allow us to do? How soon? Palimpsests appear clean to the naked eye, but to a technological eye the writing’s still there. This artificial gaze (unlike the human one) grows sharper as the years pass: picking out more and more signal from the noise. Historical crimes once considered unsolvable might soon be cracked by increasingly sophisticated uses of forensics and genomics, and so will historical omissions.

Unfortunately, the same fruits of technology will be repurposed to become tools of tyrants and monsters. An advanced deep learning algorithm might be able to recover Yezhov, but a far simpler one would be able to scramble or distort the image to make this impossible, in the same way that a simple freeware program like DBAN can, within seconds, wipe out data in such a way that the entire NSA, given infinite money and years, couldn’t get it back. Entropy’s a bitch. The USSR tried to delete their citizens, but failed because they didn’t have a delete key. The will was there, the technology wasn’t. Seventy years later, a real technological delete key is either coming soon or already here. When it’s finally used, we’ll be the last to know.

Stalin used more crude methods to reframe reality. Ironically, his attempts were rather democratic: he tried to unperson his enemies by public consensus.

Consider the absurdity of the Beria omission. The NKVD wasn’t raiding homes and confiscating copies of the Encyclopedia. They (via Sovetskaya Entsiklopediya) were issuing instructions for citizens to voluntarily censor their own books. They were explaining what needed to be done with full confidence that their instructions would be followed. People were at perfect liberty to leave the page on Beria in the book, but they didn’t think that would happen. After all, history had been revised. A new world existed, one in which Beria didn’t exist. Why would you possibly want an entry for a nonexistent person in your encyclopedia? A lot of decisions make more sense when you let go of assumptions that the truth is unchangeable.

That’s maybe the cruelest, most humanity-defying thing about the USSR in this period: the way they made the people party to their own destruction. It’s not that difficult to crowdsource oppression: East Germany’s Stasi, over the course of its existence, had over 600,000 informants , a substantial proportion of the population. It’s a frightening thought that if we ever disappear, it won’t just be the work of Big Brother but also Big Sister and Big Daddy and Big Mommy and Big Neighborhood TV Repairman. Everyone will collaborate on your unpersoning without shame, perhaps without awareness. They’ll do it out of rightness. A new reality has been imposed where you don’t exist, and thus you don’t. It takes a village to raise a child (as the aphorism goes), and it takes a village to bury a child, too.

No Comments »

Most stories have an endoskeleton: a theme that lies inside them like a set of bones. Sometimes it’s the same bones as another story: remove the flesh of plot from Lord of the Rings or Star Wars and you’ll find the skeleton of Campbell’s Heroic Journey. Autopsy a random romance novel from the 70s or 80s and the skeleton will be the Three R’s (Rebellion, Ruin, Redemption). Some stories are thin, their thematic skeleton close to the skin, while others are fat: you have to delve deeply through the narrative’s flesh, muscle and organs before you find it.

But then you have stories that have exoskeletons: their bones are on the outside. The theme sits on top of everything else: there’s no need to autopsy such a body to discover its skeleton, it’s there in plain view, and often it’s the only thing you see.

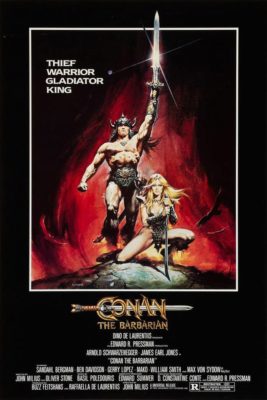

Conan the Barbarian is an exoskeletal movie, virtually all theme and zero story. Every character is an archetype, every plot point is as predictable as the movement of the stars, and the symbolism is very blunt – a Freudian psychoanalysist would suffer coronary thrombosis comparing swords to phalluses in this movie. It’s a stirring and powerful experience. Every scowl, drawn blade, and bombastic orchestral sting exists in service of myth. Conan the Barbarian is held high by mighty iron pillars of theme.

In ancient Hyboria, a tribe of Cimmerians is massacred by cultists of a dark snake god, and a blacksmith’s son is taken captive and sold into slavery. He grows to adulthood chained to a mill, revolving in endless circles. Somehow, this turns him into a muscular titan. Real slaves are skinny, haggard, and old before their time. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s body was clearly built by gym workouts, steroids and protein shakes. But that doesn’t matter, because the thematic through-line (“Conan has performed great labors and become mighty, that he might escape and seek vengeance against Thulsa Doom.”) vetoes logic and realism.

Conan the Barbarian is not faithful to any one Robert E Howard’s story (the Conan of this movie has more in common with Kull the Conqueror), but it’s faithful to Howard’s storytelling. It’s the sort of thing Howard would have written.

Howard, more so than the others of the “Weird Three” (Lovecraft and Smith) was indebted toward the lower side of pulp. He wrote action well, and his stories rely on energy and speed – they’re as streamlined as the mechanical rabbits that greyhounds chase. This also led to a certain carelessness. Lovecraft and Smith would carefully construct a setting: Howard threw up plywood constructs and then smashed them beneath stampeding Hyborian horses. Here’s what I mean:

Chunder Shan, entering his chamber, closed the door and went to his table. There he took the letter he had been writing and tore it to bits. Scarcely had he finished when he heard something drop softly onto the parapet adjacent to the window. He looked up to see a figure loom briefly against the stars, and then a man dropped lightly into the room. The light glinted on a long sheen of steel in his hand.

‘Shhhh!’ he warned. ‘Don’t make a noise, or I’ll send the devil a henchman!’

The governor checked his motion toward the sword on the table. He was within reach of the yard-long Zhaibar knife that glittered in the intruder’s fist, and he knew the desperate quickness of a hillman.

The invader was a tall man, at once strong and supple. He was dressed like a hillman, but his dark features and blazing blue eyes did not match his garb. Chunder Shan had never seen a man like him; he was not an Easterner, but some barbarian from the West. But his aspect was as untamed and formidable as any of the hairy tribesmen who haunt the hills of Ghulistan.

‘You come like a thief in the night,’ commented the governor, recovering some of his composure, although he remembered that there was no guard within call. Still, the hillman could not know that.

‘I climbed a bastion,’ snarled the intruder. ‘A guard thrust his head over the battlement in time for me to rap it with my knife-hilt.’

‘You are Conan?’

‘Who else? You sent word into the hills that you wished for me to come and parley with you. Well, by Crom, I’ve come! Keep away from that table or I’ll gut you.’

The setting is ancient, but the prose is modern. The dialog sounds like it’s from a hardboiled detective novel (you almost expect Chunder Shan to offer Conan $25 a day, plus expenses), and anachronisms like “the devil” and “parley” sit oddly in a tale of a vanished age.

For better or worse, this how the movie goes, too. Take away Conan’s mythic grandeur, and what’s left? “A rich man hires a tough to rescue his wayward daughter.” That’s a detective story. In fact, it’s the detective story. It’s the same basic plot as The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler and countless others. Everything beneath the exoskeleton is pure pulp.

Likewise, the movie captures Howard’s eclectic setting. Low-budget grindhouse films had a reputation for shooting with whatever props and costumes were available (leading to movies about roller-blading samurai, etc) and Howard’s stories have a similar feel. In The People of the Black Circle (quoted above) we get a weird amalgamation of real-world cultures, and Conan likewise throws together Mongols, Vikings, Indians, and everything in between. As Zack Stenz once pointed out, the movie owes quite a lot to 70s California beach culture. The story, written another way, could be phrased as “a Venice Beach bodybuilder and his hapa buddy do drugs, get laid, and fight a cult that exploits hippies.” Gerry Lopez (Subotai) was a surfer friend of director John Milius. Most of the remaining cast are athletes.

Some roles are oddly cast, but the most important one – that of Conan – is dead on. No role has ever suited Arnold more, except perhaps the Terminator. His overwhelming physicality sells him as a mightly-thewed barbarian, and his uncertain, rumbling, learning-to-talk diction adds verisimilitude. When you listen to Arnold speak, you don’t doubt that you’re hearing the beginnings of human language.

There are depths to Conan, but the surface is predictable. Its characters are so archetypal that they can’t do anything interesting or surprising. All of their motives are clearly spelled out, and the viewer is never in any doubt about what will happen – what must happen. Some movies are like taxis, slyly taking you on the scenic route through town if you’re not watching the meter. Conan is more like a train, pulling into the station, then leaving at a certain time on a fixed path. And since Conan is hardly the first film to adapt such mythic material, the train’s travelling down a route you’ve seen many times before.

But most people consider regularity in their form of transport to be virtue, not vice, and maybe the same is true for stories. For the rest of us, Conan the Barbarian’s the perfect movie to watch if you’re twelve, or want to remember being twelve.

No Comments »