I am dead inside. The outside’s still in top shape, though.

* * *

Let me preface this by saying smartphones are bad. It sounds like cutting-edge observational comedy from a 87-year-old, but it’s also, unfortunately, the truth.

They stunt your brain, wither your genitals, and turn you into a sad, edentulated turkey addicted to algorithmic dopamine dispensers and with a neocortex cordycepted by propaganda from some Macedonian troll farm. They’ve turned every 14-year-old into a radicalized transgender vegan with the vocabulary of an English Lit grad and the ideological horizons of a Stasi thug. They force me to design sites that can be read on a screen 400 pixels wide. Unbelievable. You know how we handled 400px screens back in the good old days? With the message “this website is best viewed at 1280×720 resolution. Dipshit.”

But smartphones have some redeeming qualities.

They give kids a childhood better than mine.

A week or two ago (inspired by Tom Ewing’s Popular blog) I began listening to a Spotify playlist: Every US Number 1, 1960-2021.

It was fascinating and revelatory, an archaeological dig that began at the bottom. I was hearing hundreds of old songs, the ghosts of music past, and each of them produced a unique reaction in me. Confusion, entertainment, boredom, curiosity, recognition, and white-hot excitement when I discovered something great.

I’ve learned things, and have filled in some empty spaces in my musical understanding. It’s now clearer how Philadelphia soul became disco, for example. It’s also clear that TV always had a deathgrip on the radio star; for decades you can pinpoint the popular TV shows and movies from the titles of #1 chart hits (in 1976-7: “Theme from Mahogany,” “Theme from SWAT,” “Love Theme From A Star Is Born (Evergreen)”, “Gonna Fly Now (Theme From Rocky)”, “Star Wars Theme/Cantina Band”), although this trend is less strong now.

It made me more aware of how the sausage is made, and how much the charts (supposedly dictated by buyer taste) are actually shaped by arbitrary engine tweaks of the music business. For example, hit singles now stay on the charts far longer than they once did. In 1975 there were thirty-five number ones, most of which charted for a week. In 2015 there were eight, with each song staying at the top for an average of 6.5 weeks. This is because digital music (which occupies no shelf space, and no FTC airwaves) has removed the external pressure for a song to exit the chart quickly.

Are the #1 charts an accurate reflection of what the public likes? I don’t think so. Much is missed when you only view the tips of icebergs. Important shifts in music (punk rock, heavy metal, grunge) came and went without ever hitting #1, at least not in pure form. The only progressive rock #1 was the disco-infused “Another Brick in the Wall”, released long after both genres’ respective peaks. The first appearance of a massive new genre is often a joke. First they laugh, then you win.

All of this was interesting. But as I entered the 90s, my mood turned sour.

I became irrationally angry at what I was hearing, and had no patience with it. Up until that point I’d hit the skip button on only two songs: “We Built This City” by Jefferson Starship, and “We Are the World” by USA For Africa. I was proud of that. It was nip and tuck for several others: “My Ding-A-Ling” by Chuck Berry escaped the guillotine by a hair’s breadth, but escape it did. Thirty years. Two skipped songs.

But now, I was skipping every fourth or fifth song, usually after a few seconds. I couldn’t stand them. At times I felt something like light panic, as though TLC and Celine Dion were tracking mud through my head. The musical journey had become awful.

I soon realized why: I grew up in the 90s.

These were the songs of my childhood. I wasn’t just replaying old music, I was replaying bad experiences. A song from the 1960s, however terrible, could never be more than a historical curio. I had no personal relationship to it. But imagine seeing a bathroom wall full of profane graffiti and laughing at it…but suddenly you see your phone number, and your address, and a crude caricature of your face. CALL [YOUR NAME] FOR A BAD TIME.

You will no longer laugh. That was what it felt like for me entering the musical 90s.

I hated my childhood. A heap of miserable and worthless years.

To be clear, I was not, exempli gratia, “abused.” I was not, exempli gratia, “interfered with”. I was not, exempli gratia, “forced to perform Wagner’s Parsifal wearing leather chaps in a Penrith borstal”.

That’s part of the problem. What I remember most of all from my early years is…is nothing. A toxic kind of nothing. A very large desert full of bones. Easier to define it by what wasn’t there. Non-events. Non-happenings.

I remember being very bored, almost all the time.

Boredom is a thing we’ve nearly eradicated, like smallpox. Children today don’t know how lucky they have it: they attend nightmarish schools, and go on to hellish jobs, but they seldom have to be bored.

But imagine having literally nothing to do. Imagine having endless free time, and nothing to fill it. Nine or ten differently-painted walls to stare at. A revolving ceiling fan scythes endlessly, reaping harvests of dead air. Morning, noon, evening. Hours stacking up like crushing granite blocks on your chest. On a windowsill a fly twists and turns upon a cobweb strand. Its dying whine fills your horizon. Your stimulus-starved brain amplifies everything; quiet sounds become thunder, specks of dust on windows become impressionistic masterworks. The needling buzz pours out to cover your entire consciousness, and when the fly finally dies, part of the cosmos blows apart and goes dark.

Boredom.

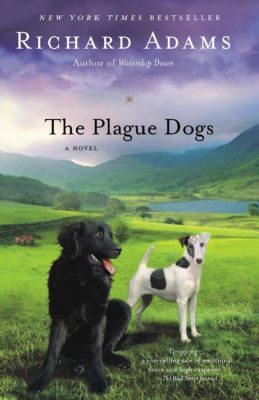

You’ve read and re-read every book in the house, even the thesaurus. That was entertainment. You are a major problem at a Scrabble board; you know words like “syzygy” and “tmesis” because you’ve read the thesaurus cover to cover.

Boredom.

You are kept bored by parental diktat. Videogames are Considered Harmful because they Rot Your Brain. The books you take home from the library are ruthlessly scrutinized for adult content. Thank God you weren’t exposed to the bodice-ripping, throbbing-with-passion novels of Terry Brooks and Jeffrey Archer.

Boredom.

Your memories are of literally having nothing to do for days on end. Every possible plan to entertain yourself is cut down by you’re a child. You can’t drive anywhere, because you’re a child. You have no money to take public transport, because you’re a child. You can’t explore the neighborhood, because you’re a child. You do it once anyway, and a neighbor finds you, gives you a stern talking to, and brings you back home. Kids aren’t supposed to wander around: they’ll get abducted by roving gangs and forced to perform Parsifal etc.

You grow up in the suburbs. Sometimes you visit relatives out in the country, in what is presumed to be an enriching experience for you. But you hate the countryside. Now you’re bored in a place you don’t like. Adults have an odd fascination with nature that you will never understand. The Australian rituals of “bushwalking” and “going walkabout” remain mystifying to you. Hello? What’s fun about this?

Australia is an ugly fucking country. Every tree and plant is a fortress built to resist siege from blazing sunlight and petrifying salt. Our most iconic tree – the Australian eucalyptus – is twisted and pathetic, a scarecrow pleading for water. It ranks among the ugliest trees in existence. Australia’s national plant – the golden wattle – looks like mould growing on expired food in your fridge.

Australian wildlife is contemptible. The wombat, possum, et al all look distinctly off, as though a dim child tried to draw a cat or dog and failed. All of them have mechanical defects. The Australian Coat Of Arms has an emu and a kangaroo. Why these two animals? Because they cannot walk backward, only forward. I appreciate the symbolism, but aren’t these obviously rubbish animals? For fuck’s sake, how many millions of years does it take to evolve reverse gear?

Our mammals are bumbling simpletons without any survival instincts. They’re so maladapted it’s a miracle any are still alive – they’re Dervish savages and it’s a Maxim gun world. Drive along any outback road and see the both shoulders strewn with bloody fur and viscera, where wallabies and wombats exploded like hand grenades. It’s pathetic how weak they are. The cars aren’t even trying to kill them, for God’s sake. Are you an apex predator who’s struggling on its home turf? Here’s a tip: come to Australia. You’ll never go hungry again. All our animals drew a pair of deuces in the Darwinian lottery.

You feel far more respect for invasive species, particularly cats. Like Art Spiegelman, you liken cats to Nazi Germany. Yes, they’re evil. But doesn’t one also admire their competence? Their fearful symmetry? The ease with which they shred the lesser orders? Who isn’t impressed by the feline blitzkrieg?

And where Australian wildlife isn’t pathetic, it’s abhorrent. You have a horrid memory of playing alone at Blackheath, pulling chunks of bark off trees. One piece comes away, and it feels strangely heavy in your hand. Through cracks in the bark you see eight sickeningly huge legs, outspread like spokes on a wheel. Whatever’s clinging to the other side is at least fifteen centimeters across. You throw the bark to the ground, run away, and hope you never see a tree again.

The world in general was more boring in the 90s. Turn on the TV, and unless you had cable you had your choice of “shoddy soap opera”, “shoddy movie with cheap licensing rights”, “shoddy show for preschoolers” and “channel whose quality cannot be assessed because it’s in Swedish”. If you were fortunate enough to have cable, your cultural cup runneth over! You now had twenty shoddy soap operas, twenty shoddy movies…

In the latter part of the 90s, the internet enters stage. This ameliorates boredom at the rate of 56 kilobits a second, but again, your usage of it is policed. You are told that the internet is untrustworthy and will pollute your brain with lies. This is entirely correct. Fifteen years later, some of those same people email you links about Hillary Clinton conducting Satanic rituals involving the gargling of fetus extract.

But more. Deeper. Deader.

Imagine you have no friends. Some problems are doubled when shared, some problems halved, and boredom is the latter. Having nothing to do is bearable when there’s someone to commiserate with.

But you have no friends, and it’s because you have a terrible personality. Some folk have a halo effect that casts a positive aspect on everything they do. Their insults come off as witty jokes. Their boasts come off as confidence. They lie or break a promise and it makes them look dashing and romantic, like highway outlaws. Playing by the rules is for scrubs.

You have a negative halo. A black hole surrounds you. Compliments sound false in your mouth, explanations sound like showing-off. You hate the sound of your own voice.

You, like all unpleasant nerds, rewrite the script so you’re the good guy in your social ostracism – you don’t get invited to parties because you’re that much more refined than all of those barbarians. But you aren’t refined. You’re as maladapted as the rest of Australia’s wildlife.

Let’s talk about bullying.

You wouldn’t mind bullying if it was clever and skillful. You think you’d enjoy being placed at the center of Borgia-like power struggles, forced to keep your friends close and your enemies closer. Sounds like fun.

But bullying isn’t clever and skillful. Any idiot can be a bully. It takes an order of magnitude more cunning and bravery to resist a bully than to be one.

Here’s a rough guide on how to do it. First, become skilled in some obscure thing that not many people can do. Or learn some obscure fact that not many people know. It might be as simple as the fact that toads belong to the Bufonidae family. Repeat “toads belong to the Bufonidae family…toads belong to the Bufonidae family…” to yourself in bed until it’s firmly in your memory.

Then, go up to the person you want to bully. “Hey, dumbass. What family do toads belong to?” They won’t know. Then, you can say “Bufonidae!” and laugh. Gotcha! You knew something they didn’t! You set them a test, they failed, they’ve lost social capital as a result.

…But this kind of bullying isn’t very effective in the real world. Most people don’t care about general-knowledge trivia items. There’s zero status involved with knowing that toads are Bufonidae (if anything, there’s possibly negative status involved.)

However, there are other types of meaningless skills that are actively rewarded by society. Sports, for example, are socially enshrined as a status marker from middle school onward: it’s something cool people are good at. Not everyone is athletic, or wants to be, so it’s also a perfect, risk-free way of establishing yourself as a success, and others as a failure. You aren’t good at sports, and hence are a failure.

You hate sports. Deeply hate them. They make you feel murderous rage. It’s like bullies hacked the computer simulating the universe and hand-coded a feature that perfectly rewards them.

You don’t recall the moment everyone you knew began caring about sports. One moment nobody did, then everybody did. It was as if they’d taken night classes on how to be normal and you’d had missed out. Soon sports became the big difference between you and others, a gulf that widened with years and exists to this day. Here is CS Lewis:

“Never, except in the front line trenches (and not always there) do I remember such aching and continuous weariness as at (school). Oh, the implacable day, the horror of waking, the endless desert of hours that separated one from bed-time! And remember…a school day contains hardly any leisure for a boy who does not like games. For him, to pass from the form-room to the playing field is simply to exchange work in which he can take some interest for work in which he can take none, in which failure is more severely punished, and in which (worst of all) he must feign an interest…Consciousness itself was becoming the supreme evil; sleep, the prime good. To lie down, to be out of the sound of voices, to pretend and grimace and evade and slink no more, that was the object of all desire–if only there were not another morning ahead–if only sleep could last for ever!”

An astute man, that Clive Staples. If it’s not clear from context, “games” means organized sports such as rugby and cricket.

Another memory. You’re kicking a soccer ball against a complete dipshit in a sea of dipshits. He’s two years younger, has a prissy little rat tail, and is almost laughably better: the ball seems to flow and weave around him, as if it’s metal and his Nikes contain neodymium.

He clearly practices for hours every day. And why wouldn’t he? He might not have any love for soccer, but he loves the status, the fact that soccer gives him power over other boys. What king will not fight to keep his crown?

The adolescent asshole stops toying you with you and trips you up, taking possession of the ball. “And I was going easy on him!” he hoots, earning laughs from some other boys. Every level of what’s happening feels ludicrous (“I won against a kid who doesn’t know how to play, and get this…I was going easy on him!”) but to the others it seems completely normal. Just another way of sorting the hackers from the non-hackers.

Everyone is staring at you now, waiting to see if you’ll do something funny like cry or piss yourself. Something odd is happening at your core. You feel rigid, but there’s a sense of volatile emotions underneath that rigidity, like magma flowing beneath a hardened crust. Explosion or paralysis. Explosion and paralysis. You don’t know where you are or what you’re doing. Your body is no longer under your control.

One impotent thought shudders along failing mental telegraph lines. If I had a Stanley knife in my hand, I would put it in him. Without hesitation, I would do this.

You can see it, smell it, hear the screams. You would snap it open and drive it so deep into this ratfucker’s face that the mark stays on him forever, that his very skull will bear your handiwork when he’s buried. You want to destroy him. You want to write hieroglyphics into his bones. It’d be easy to inflict unbelievable pain on this kid – soccer is all he knows. He’s not a survivor anymore than the wombats killed on the freeway. But what would happen after that? You might as well go right on stabbing, because there’s no going back.

Instead, You mutter something and walk off with a shrug, as if it’s no big deal. Clearly it was, though, because you remember it.

Have I been dishonest in the above accounts? Have I persiflaged? Meandered? Lied? Traded in the coinage of cliche, self-pity, or banality? Perhaps. It’s logical that a negative halo would persist over my writing, too.

But childhood and I didn’t agree. It seemed it would never end, and I’m glad that it finally did. It was a tedious mass of days, both for reasons unavoidable (bad) and avoidable (worse). They weren’t the best years of my life, they were prison years in which I was not my own master.

No Comments »