The greatest comic of all time, according to some. This is a small exaggeration. After exhausting, grueling, and – dare I say it – faintly erotic analysis, I bring you the truth. It’s the greatest comic of its first week of issuance in 1980. Perhaps the weekend after, too. Best I can do.

The story is complete rubbish: The Incal has a “toddler smashing action figures together” plot where the MetaBaron battles the HitlerRodents while the GlorpFucks unite the PlotStone with the QuantumMatrix and all seems lost but then the SlamPig Brigade arrives and blows up the NightmareBot and on and on and on (and on and on). Comics like The Incal don’t “end”, they merely stop having new issues produced. The fact that it has six volumes is incidental: it could just as easily have gone on for six more, or sixty more, or until Jodorowsky died.

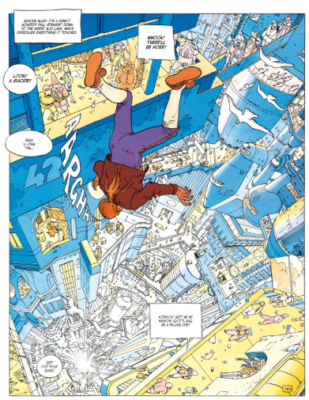

People describe it as “surrealist” but it’s not, they describe it as “philosophical” but it’s not, etc. Visually it evokes those psychedelic 70s-80s animated movies like Wizards and Fantastic Planet, as well as French “bandes dessinées” comics such as Tintin. It consists of very powerful and imaginative imagery, with the plot noisily emitting a dense cloud of complications. It also reminds of Metal Hurlant/Heavy Metal – which it has to, because its artist Mœbius was an important figure in that comic. Some of Mœbius’s famous visual motifs are present in the Incal, such as Arzach’s white pterodactyl, here seen as the hero’s comical sidekick, Deepo.

Arzach is a fearsome beast, and I would recommend it over this comic. It’s short and confusing, but you feel in your bones what it’s trying to do. It stuns and awes the senses with visuals of alien worlds, making characters seen both big and small, and reading it is like drunkenly climbing a ladder to heaven. The absurd visual style (merging prehistory and the far-future) only adds to the grand, hallucinatory effect.

As does the fact that it’s wordless. Some comics gain from having text, others lose. Neil Gaiman once wrote that he “read” some Metal Hurlant comics (not understanding French) and loved them. Later, he read those same stories in English translation and was disappointed – now that he could understand the words, they seemed curiously small. I had a similar experience with certain untranslated Junji Ito manga. It wasn’t that they were bad, but my imagination made them seem much greater than they really were.

The Incal is probably a similar case: more enjoyable if you can’t read the words and only have Moebius’s imagery to guide you. The comic book emerged out of Jodorowsky’s 1975 attempt to adapt Frank Herbert’s Dune. He’d planned a 10-hour opus that would have made Heaven’s Gate look like a poster child for minimalism, featuring HR Giger, Mick Jagger, Salvadore Dali, spiritual and psychedelic themes, etc. He was unable to secure funding for this project (film studios have found more convenient ways to declare Chapter 11 bankruptcy) and much of the work he did was repurposed into The Incal. There’s little evidence of Dune in the final comic, but I doubt Jodorowsky’s planned film would have had much connection to it either.

There’s some cool moments. The in-media-res opening image of sleazy detective John DiFool being flung down “Suicide Alley” is striking and often imitated. The grungy tone of some of the urban scenes might have been an influence on eg, Blade Runner, just as the skulking bounty hunter MetaBaron reads as an early version of Star Wars’ Boba Fett (Fett’s first public appearance predates MetaBaron’s, but I’m fairly sure MetaBaron was conceived of earlier). There’s no shortage of ideas here, some you’ll recognize in later, more famous products. I have no idea to what extent this is conscious “inspiration”. Perhaps Jodorowsky merely put his hands on some ideas that were already circulating in science fiction and gave them form. Most pertinently: the world of The Incal feels slimy and lived-in, the politicians are corrupt, religious figures are hypocritical, everyone’s sex-obsessed and venal. It depicts a lived-in future, perhaps a died-in future. But spiritual purity is possible, no matter how debased you are.

The Incal definitely has flaws, but it also has strengths. It’s a highly charming work, always easy to like. It has a sense of humor – the pangender “Emperoress” got a laugh out of me. Fans of Jodorowsky’s films will probably love this, as it’s full of little echoes of El Topo and The Holy Mountain (the absurdity of Deepo becoming a religious icon is straight out of the latter movie).

But ultimately, it’s just not as clever as it wants to be. It needs writing to match Moebius’s art – either that, or no writing at all. The plot’s just standard science fiction and fantasy stuff that was done better before (and certainly better afterward), and although it’s more intense than the average Bronze Age superhero comic, but still hews to the superhero formula. The story is written to be both collapsible and extendable. It’s made up of details, none of which are essential. If you have too many pages, Trim some details. Conversely, you can extend a story by adding extra details. It’s always apparent that “story” is just a secondary concern to most comics. Their first one is to take up space. Their allegiance is to the space. They have to fill up a certain amount of page area and no more, and this locks them into place like iron bars. Nobody wants to pay for a comic with a blank page. Or half a blank page. Nor will they pay for a comic that ends mid-climax with “sorry, ran out of space! Send me a letter if you want to know the ending!” The story must fit. You’d think that the advent of webcomics would cause artists to break free of these limitations, but most don’t.

No Comments »