Wally/Waldo is a man in a red striped jumper and bobble hat, hiding somewhere in a complicated picture. Why does he wear such a distinctive outfit? Why not wear black clothes and blacken his face and hide in a coal mine?* Because Wally’s not actually hiding. You’re supposed to find him.

The appeal of games – from Martin Gardner puzzle books to Super Mario Bros – is this: they want you to succeed. Games, by definition, are designed so you can win. Reality isn’t like that, and people addicted to games are often addicted for good reason.

But Where’s Wally puzzles are fascinating even when you’re not an addict. They carry a magical enchantment – one glance sucks you in, and then you’ve spent five minutes looking for a ridiculous bobble hat. Or ten minutes. Or however long it takes. I’ve heard disturbing stories of people posting edited puzzles online with Wally removed. And you thought you didn’t support the death penalty.

I wonder how many children were subconsciously influenced to become programmers by these books. Finding Wally takes skill as well as luck: it’s fundamentally a search problem, and there are several ways to find Wally.

The most obvious method is a blind fishing algorithm; let your gaze wander around on the page until you spot the striped jumper by chance. This is a poor method: it’s hard to remember the places you’ve already looked and you’ll probably check the same place multiple times. Also, the human eye is a biased sampling tool. It’s drawn to busy, high-interest areas, which won’t necessarily contain Wally.

A better method is to cut the page into a 10*10 grid of tiles (either with your eye or a knife), and examine it square by square. You’ll find Wally eventually, but it might take a long time: if you start looking top-left and Wally’s at bottom-right, you’ll have to check every single tile.

Is there a faster way? Yes. Remember that not every tile is equally likely to contain Wally. Some contain empty water or empty sky. More fundamentally, you’re not looking for Wally; he doesn’t exist, you’re looking for an illustration on a page containing red ink. Any square without red will ipso facto not contain Wally, so throw all of them away.

You are now left with a small number of tiles that maybe contain Wally. Speed up your search still further by remembering that Where’s Wally is a book, and the author rarely puts Wally on the edge of a page (because you’ll look there when you turn the page), or in the top left corner (because there’s a text box there describing the environment). Arrange your tiles so that the unlikely ones are on the bottom. Using this method, you’ll have tiles sorted high-probability to low-probability, and you’ll probably find Wally after picking up just a few. That is, if you don’t suffer a fatal heart attack from EXCITEMENT.

It’s possible to solve a Where’s Wally puzzle quickly, just as it’s possible to eat an ice cream in ten seconds, but part of the appeal is taking your time and enjoying the art. Where’s Wally pictures are packed with more detail than a Persian carpet, containing so many people that they don’t even look like people: they’re objects, like a strew of spilled jellybeans. Author Martin Handford owes a debt to horror vacui, an art approach that relies on filling everything with something.

Despite occasional verisimilitude (a tiny exposed breast on page 2 has earned Where’s Wally repeated bans from bookshelves), the overall effect is to distance you from life. Everything becomes a sea of human-shaped noise, as dead as a TV screen tuned to static…but you have to find a man in the static.

Again, there’s a weird vocational training aspect to Where’s Wally, turning kids into private eyes. Can you find a certain person who’s identical to the rest…except for a bobble hat? How much noise can you sift through to find a signal? There could be a Where’s Wally to programmer pipeline. There could also be a Where’s Wally to NSA analyst pipeline. Edward Snowden, Chelsea Manning, and Julian Assange had the misfortune of becoming Wally in real life.

I remember an animated Where’s Wally cartoon that missed the point: they turned Wally into a heroic protagonist who goes on adventures, which is necessary for dramatic purposes but destructive to the spirit of the books. He’s supposed to be a face in a crowd. He could be any of us. He’s not special – or is he? How would we even tell? Are we Wally to someone else? If so, how easy should we make it for them to find us?

We live in a Where’s Wally puzzle as wide as the Earth. We’re born knowing nobody except a few family members. From the remaining 99.99999% of the human race, we’re supposed to locate friends, associates, and romantic partners. Some people find Wally with instinctive ease. Others struggle, and rely on sorting algorithms such as dating sites and social media. And still others don’t try at all, because failure is terrifying.

Climb up to a high place in a busy city, and look down at the thousands of people flowing in pulses, as if a great beating heart is driving them. Think of how little you know about them. Some of them rescue pets from burning buildings. Some of them rape and strangle children. The world is a huge inscrutable horror vacui of saints and sinners. Do these people want to help you? Harm you? You don’t know. You’re forced to guess based on tiny signs, small clues. Instead of a striped jumper it might be a word, a gesture, or an insincere smile that doesn’t reach the eyes. Perhaps this is why Where’s Wally is eerily compulsive: we hear the echo of our lives inside it.

Where’s Wally is training.

For something.

(*obviously, this is blackface, Martin Handford would be #cancelled and branded an international hate criminal, and Wally himself would become a symbol of racism, starring in new books such as Where’s Wally at the Nuremberg Rally, Where’s Wally at Auschwitz-Birkenau II, and Where’s Wally at the 2021 Academy Awards.)

No Comments »

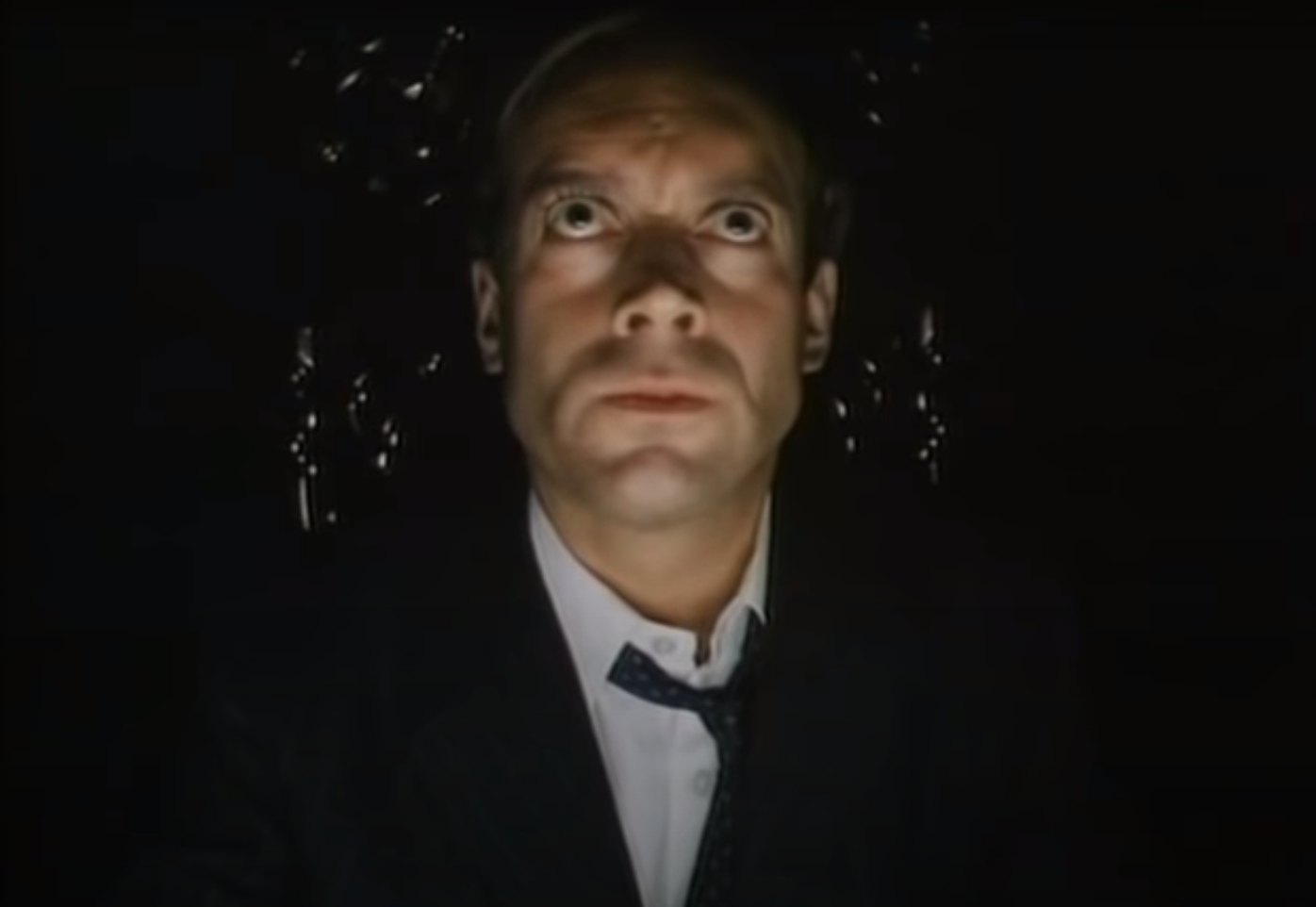

Max Headroom is a “computer animated” TV host from the 1985 UK music video series The Max Headroom Show, the 1985 telemovie Max Headroom: 20 Minutes into the Future, and the 1987 science fiction series Max Headroom.

Air quotes because he’s not computer animated, he’s actor Matt Frewer with latex and foam stuck to his face. Computer animation cost tens of thousands of dollars per minute in 1985, and Victorian chimney-sweeper logic kicked in: “screw cutting edge technology, let’s send an eight-year-old boy up the flue.” In 2020, computers steal jobs from humans. In Max Headroom‘s time, we stole jobs from them.

Max’s character is jarring and wrong, st-st-stuttering like a stroke victim as he reels of Dangerfield-esque one-liners. The idea is that he’s a human consciousness digitized imperfectly – a half-a-human. You can’t be at ease while watching him, it’s like eating dinner off a cracked plate. The fact that he was broken ironically made him complete: nobody would remember his unfunny jokes if they’d been delivered in a normal voice. He’s a vivid example of glitching and ugliness used for artistic effect (note the similar stuttering used in Paul Hardcastle’s “19”).

Max is a one-idea character, but the idea proved highly successful. He’s widely recognized (and parodied). There’s a Hello Kitty aspect to Max: everyone recognizes the character, but few can tell you where he’s from, or even where they first saw him. For some, it was the New Coke commercial; for others, Max Headroom just exists, a creation without a creator, floating freely in conceptual ether.

The character, however, emerged out of a very specific set of circumstances.

In 1981, video killed the radio star, and stations such as MTV needed hosts to talk between records (where “talk” means “sell products”). Unlike radio hosts (who were heard but not seen), video jockeys needed to look attractive, or at least interesting in some way. They couldn’t, for example, be a man “shaped like whatever container you pour him into” (in Patrice O’Neal’s immortal roast of chubby radio host Jim Norton).

Most stations wanted their hosts to be hip, the UK’s Channel 4 took a different path and made their host a weird, uncool goober, whose lame one-liners are further mangled by a layer of digital distortion.

It was a great idea: Max Headroom won’t ever become lame: he’s already maximally lame. He won’t lose dignity when he plugs a sponsored product: he had no dignity to begin with. Rock stars will want to talk to him: he’ll made even the most incompetent cokehead seem like a scholar.

But Max Headroom didn’t become famous from the music video show.

It soon occurred to Channel 4 that this character might work in a sci-fi drama, and the result is a dated but interesting cyberpunk film that owes a lot to Blade Runner and Brazil, although made for far less money.

The film is set in near-future England, which could be described as “Thatcher, but more”. London is as black and filthy as the inside of a tar-saturated lung. Thugs lurk in the shadows, ready to kidnap you and sell your organs to body banks. Industry is ferocious, a terrifying machine running on a fuel of human lives. There are televisions everywhere, blaring idiocy.

The plot involves entertainment conglomerate Channel 23, who have invented a new form of TV ad called the “Blipvert”. Traditional 30-second ads annoy viewers and cause them to change the channel, but Blipverts allow ads to be compressed into a few seconds of high-intensity audiovisual stimulation. Ratings are through the roof. However, some people experience a side effect: they explode.

There’s some funny and effective satire where we see Channel 23 execs trying to defend Blipverts. No causal link has been proven! Surely some percentage of the population can be expected to randomly explode, right? Also, if you explode after watching an ad, isn’t it your fault in the end? We’re probably supposed to think of tobacco companies: modern viewers will think of the oil industry.

Regardless, star reporter Edison Carter (who works for Channel 23 himself) gets “too close to the truth” and suffers a tragic motorcycle “accident”. However, he’s supposed to appear on air later that day, and a bungled attempt to digitize Carter’s brain results in an odd lifeform that immediately utters the words “Max Headroom”, because that was the final thing Carter saw before his bike crashed.

Writer George Stone says British firms spent millions of pounds relabeling the “Max Headroom” signs in public garages to “Maximum Height”, due to association with the character. There’s a slight chance that Max Headroom actually cost Britain more money than it made.

The movie did not really have a budget. Its portrayal of futuristic London as an industrial wasteland is more a concession to lack of money than anything (in a stroke of luck, they were able to shoot in Beckton Gasworks, where Stanley Kubrick filmed certain scenes in Full Metal Jacket).

Yet it nails the things that are cheap: acting, and tone. A grungy and effective mood soon appears. The story’s confusing and hard to follow, but it’s not boring.

The camera-work has an aggressive, edge-pushing quality that’s as unsettling as Max Headroom himself. For example, consider the alarming way the villainous Channel 23 head Grossman is framed. Sharply underlit, and distorted by bubbled lensing in a way that emphasises actor Nickolas Grace’s exotropia. He looks terrifying, a one-man Panopticon.

Max Headroom actually doesn’t do much in this movie. The same holds true for the American TV series: the episodes explore some science fiction conceit related to capitalism and media (a reality TV show is attracting viewers through subliminal mind control, or something), and Max serves as a framing device for the story. He’s Tel-vira, Maxtress of the Byte. But isn’t that what a VJ is supposed to do? Introduce stuff, and get out of the way?

People like Edison Carter and Theora got to have all the fun, running around and solving crimes. Max is just a talking head, frozen in place, transfixed like a glitching, jittery butterfly upon a technological pin.

He has nothing to do. He just tells his idiotic jokes and becomes more outdated day by day. Matt Frewer was wont to complain about how annoying his makeup and prosthetics were (“like being on the inside of a giant tennis ball”), but the character itself was just as restricted.

Video hosts are passive, powerless ciphers, introducing the action without ever being a part of it. They’re like eunuchs guarding the sultan’s harem – yes, they know all about the deed, but they’ll never do it for themselves. It’s no surprise that the career breeds dissatisfaction, and a search for something more.

No Comments »

A “mockbuster” is a low-budget ripoff of a famous movie designed to trick you (or more likely your grandmother) into buying it. Major Hollywood films can have print and advertising budgets in the range of hundreds of millions of dollars, and just like harmless moths copy the markings of venomous wasps, a well-designed fraud can exploit another movie’s publicity blitz without spending a cent in advertising itself. A rising tide lifts all boats, but it also lifts turds.

Mockbusters are frequently masterpieces of surrealism. Their only desire is to be safe and generic, but they always feel uncomfortable, creepy, freakish, and strange. You might say they follow the rules so hard they break them.

2002’s Max Magician and the Legend of the Rings is an archetypal mockbuster. It wears its can’t-fail concept on its sleeve (or cover): Lord of the Rings was making money, Harry Potter was making money, so if you combined those things into one movie, then hell, you’d make money squared. Money times money. Hopefully this plan worked, because the director clearly had crack debt times crack debt.

What he didn’t have was a budget, actors, set designers, producers, or writers. Nobody involved in the movie seems to know what they’re doing, and some actually appear to be held on set at gunpoint. The result is an experience that has to be seen to be believed: a disastrous collage of fantasy cliches whose shamelessness is matched only by their incompetence. You feel genuine embarrassment for everyone in the zoning district.

Story? A young amateur magician called Max Majeck (you just heard the movie’s funniest joke, by the way) finds a doorway to a fantasy world under attack by a guy in a Ren Faire costume. Max saves the day by reading incantations out of a magic book, unleashing awesome spells such as “slowly levitate a few sticks of wood” and “cause several mice to appear on the villain’s shirt”. Watch out, Stephen Strange.

Everything about the movie is misjudged, including the decision to make it at all. The “fantasy realm” is clearly the woods outside someone’s house. The movie introduces an old, wise mentor character, forgets about him, introduces a second old, wise mentor, and then forgets about him. There’s a character called “Mr Tim” who refers to his wife as “Mrs Tim”, probably because it was too much work to come up with a woman’s name.

Like any truly bad movie, it’s actually hard to critique: it’s a firehose of awfulness overwhelming any cogent attempt to analyse it. An example of the rollercoaster ride the film takes you on: there are elves. They have pig ears. The pig ears don’t match their skin tone. The queen of the elves is played by the same actress who plays Max’s mom. She speaks with the same Midwestern accent in both roles. I literally can’t focus on any one thing because there’s always something worse distracting me.

But the audio stands out as exceptionally horrible. The music is completely inappropriate, sounds like it came from a free stock library, and was queued into the film by a deaf person. Countless lines of dialog are dubbed, suggesting that their original audio was spoiled somehow. They must have rewritten the dialog too, because the lips generally don’t match the voices.

I have to correct some misunderstandings the internet has about Max Magician. The first is the claim (featured on IMDB) that “There are no rings.” No, there are rings in this movie. Mr Tim’s book references magic rings. Dagda steals a green ring from Queen Belphobe.

The second misunderstanding is that it’s just a ripoff of Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter. That undersells the film’s ambition: it also rips off The Chronicles of Narnia (the talking mouse character + the children travelling between world plot point), The Neverending Story (the enchanted book), and Jim Henson’s Labyrinth (the goblins-bickering-in-the-closet scene at the end.)

It’s fairly good “make fun of bad movies” fodder. I suggest going into Max Magician armed with a few facts about it’s production, such as the fact that the weapons are literally pool noodles, or that the talking mouse Crimbil is portrayed by two different mice after the first got eaten by a snake. (You can notice this on-screen because the two mice don’t quite match in color: OG Crimbil is slightly gray, while Emergency Backup Crimbil is slightly brown. Can you identify which scene contains which Crimbil? This could be a drinking game. )

Mockbusters are designed to be disposable. Strangely, this one picked up a second life after pop culture commentary Youtube channel Red Letter Media tried (and failed) to review it. Their video was corrupt and displayed 86 minutes of static. I think my video’s corrupt, too. It displays 86 minutes of shitty movie.

(Ironically, “mockbuster” is itself a linguistic mockbuster, riding on the fame of two prior words – mockery, and blockbuster – to achieve its affect.)

No Comments »