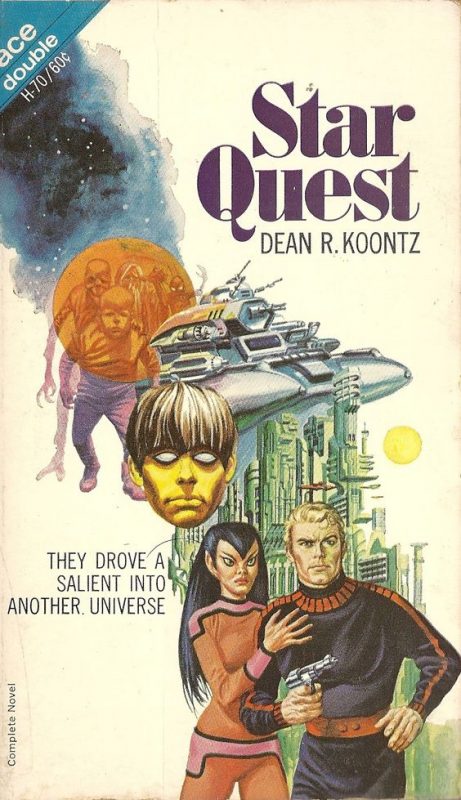

The Dean Koontz of 2022 has hair plugs and writes preachy stories about libertarian gun owners who fight supernatural strawmen for collectivism and/or postmodernism with the aid of guardian angels and/or pet dogs. The Dean Koontz of 1968 had no hair plugs and wrote Heinlein-style science-fiction.

Star Quest is his first book, if it can even be called that. It’s a 25,000 word novelette that was packaged as part of an “Ace Double”, along with Doom of the Green Planet by Emil Petaja. Ace Books told Dean that his side of the split was too short, and asked if he would accept $1250 so Petaja could get $1750. Years later, Petaja revealed that Ace Books had run the same line on him – he would get $1250 and Koontz $1750!

The story’s a military SF yarn. A sentient tank called Jumbo Ten (lol) is fighting a war for the despotic Romaghins against the invading Setessins when he suddenly he realises that he’s not a machine at all, and that his brain is from a human called Tohm (gross). This realization causes him to go AWOL mid-battle and begin searching for his missing past. Interesting, there’s a piece of Stephen King juvenilia (“I’ve Got to Get Away!”) with nearly the same basic plot.

To state the obvious, Star Quest was written quickly by a young man. It has problems typical of books written quickly by young men.

Laser cannon erupted like acid-stomached giants, belching forth corrosive froth that even the alloy hulls could not withstand for any appreciable length of time.

Why are the “laser cannon” belching “corrosive acid”? Many books fuck up their continuity, but usually not in the same sentence.

Koontz loves flowery literary passages, so our novel about a sentient tank called Jumbo Ten also has stuff like this:

But the Fates, those fickle ladies, will often change their minds and lend a hand to those they have so callously crushed before. His web of life had been spun by Clotho who immediately washed her hands of it and moved on to another loom. Lachesis, who measured the length of his strand, decided to fray it down slowly to whittle it to near nothingness. But now, just as Atropos was coming forth with her golden shears to snip it completely, Clotho had a change of heart. Perhaps, she was unemployed and restless that day, looking for something, anything to do. In any event, she stopped Atropos with a kind word and a cold stare, and began spinning again more thread…

Was “those fickle ladies” really the right phrase? Myself, I would have gone with “those goddamn broads.”

Ace Books did not use their stolen $500 to pay for copyediting, and the book contains even more spelling errors than this review. Jumbo Ten, we learn, is made of “alloyed steal”. I will allow that “He opened his corn-system” is probably an OCR error in the digital copy I found.

The story is fast paced and somewhat exciting. And it does have ideas, like a sci-fi invocation of the “multiverse” theory well before Heinlein wrote The Number of the Beast.

But Tohm/Jumbo Ten’s motivations are too stock to be interesting: he wants to go home, find his girlfriend, etc. These universal impulses are supposed to make him sympathetic, but they’re too universal: he loses his identity in a sea of other sci fi heroes who are characterised in exactly the same way. He might be convinced he’s a living person, but he does not convince the reader.

In 1968, it would have been the literary version of fast food: made cheaply and consumed quickly. But now, it’s something more: an interesting curio from a very famous writer’s past. Authors only get one first novel, and it’s fascinating that this was Koontz’s. Themes of individualism are the only thing bridging his work from then to now. Otherwise, this is a totally different writer, and a reminder that (despite arguments otherwise), we fundamentally aren’t the person we were yesterday, and also not the person we will be tomorrow.

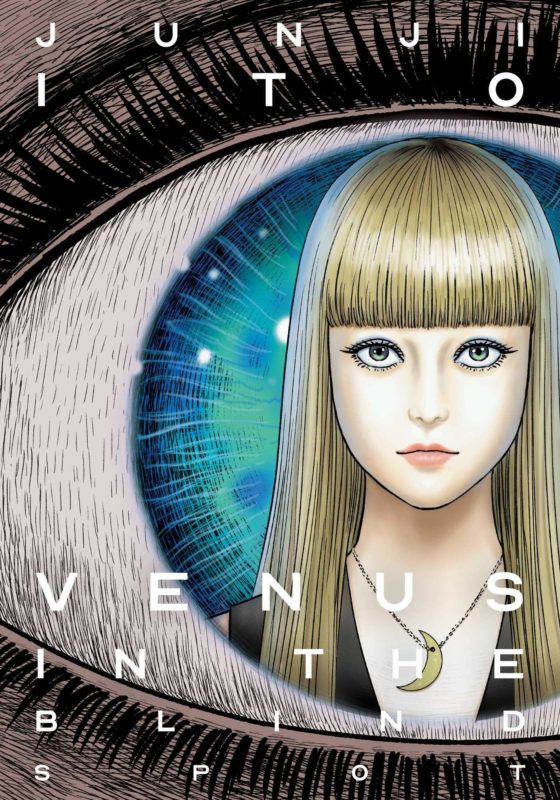

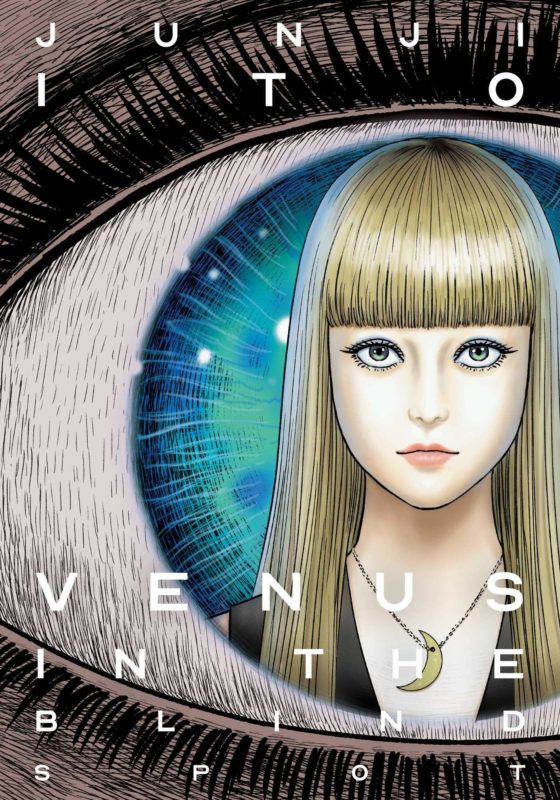

A collection of shorts from everyone’s favorite dentist, Junji Ito.

It’s an English release of The Best of Junji Ito, which was collected in 2019 by Shogakukan Big Comics Special. It’s the same basic idea as Metallica’s Garage Days Re-Revisited – odds and ends that don’t fit anywhere. Four stories are bonuses from Gyo, Remina, and Black Paradox. Three are adaptations of prose works from Edogawa Rampo and Robert Hitchens. The rest is previously uncollected material. It’s not clear why these particular stories were chosen, or why others (such as “Mystery Pavilion”, “Phantom Mansion”, etc) were missed.

Some highlights:

“Billions Alone” – 2004 Junji Ito stares into a crystal ball and perfectly predicts the world of 2022. People are forced into isolation by a sinister force that kills them when they gather together. You’ll think of COVID19, of course, but the corpses-stitched-together visual could be an equally good comment on social media, which erupted like a cancer years after the story’s release. Spot the panel that inspired The Human Centipede.

“Venus in the Blind Spot” – a sweet, weird story about a girl who vanishes from your visual field when she gets close. It’s a Tomie story with less gore, reprising Ito’s usual themes of madness, desire, female beauty, and perception. It would be a good introduction to his work.

“The Enigma of Amigara Fault” – chilling story that makes my skin try to crawl off my skeleton, even now. A landslide reveals human-shaped holes in a mountain, which some people try to enter. A really effective and sharp story body horror and claustrophobia. Overall, Uzumaki is Ito’s greatest manga, but if you want to sharpen his entire career down to a thirty page highlight, this is it.

“The Sad Tale of the Principal Post” – a man gets trapped underneath a pillar upholding his house. Nobody online seems to understand the story, but it isn’t that confusing. It just takes a common metaphor (a father supports his house!) and makes it literal. More a joke than a story.

“The Human Chair” – Rampo’s 1925 story (about a carpenter who installs himself in a hidden compartment in a chair so that he can feel women sitting on him) is a classic of Japanese horror. To experience this much voyeuristic sexual perversity you’d have to be a girl riding the Shinkansen. Although it shares a title with this classic tale, Ito’s story is more of a sequel, continuing and expanding the plot.

“Master Umezz and Me” – a very personal story where Ito discusses his fannish obsession with Kazuo Umezu, the godfather of Japanese horror manga. Umezu (who, by the way, is 85 years old and announced the launch of a new series this year) is so different from Ito that it’s always surprised me that he drew inspiraiton from him. Aside from some vague surface similarities (“supernatural immortal girl” = Orochi/Tomie, “kids surviving in a hostile wasteland” = The Drifting Classroom/Uzumaki vol 3, Bible-style apocalypse where mankind is punished = Fourteen/Remina) their work is nothing alike. The story’s a heartfelt and affectionate tribute. Sometimes we forget what it’s like to be a kid who enjoys something: it’s a pure, heliumlike joy seldom recaptured in adulthood.

Parenthetically, does Goodreads sell a licensed crack pipe that you’re supposed to light up before writing reviews?

“Viz Media’s blurb for Venus in the Blind Spot is really weird: it claims this is a “best of” collection of Junji Ito’s stories but, as far as I can tell, only one – maybe two – stories have previously appeared in print before: The Enigma of Amigara Fault and The Sad Tale of the Principal Post possibly both appeared in Dissolving Classroom. So this is a “best of” collection that features almost all-new stories!?”

Ito should make a manga about this person’s mind. It’d be his scariest work by far.

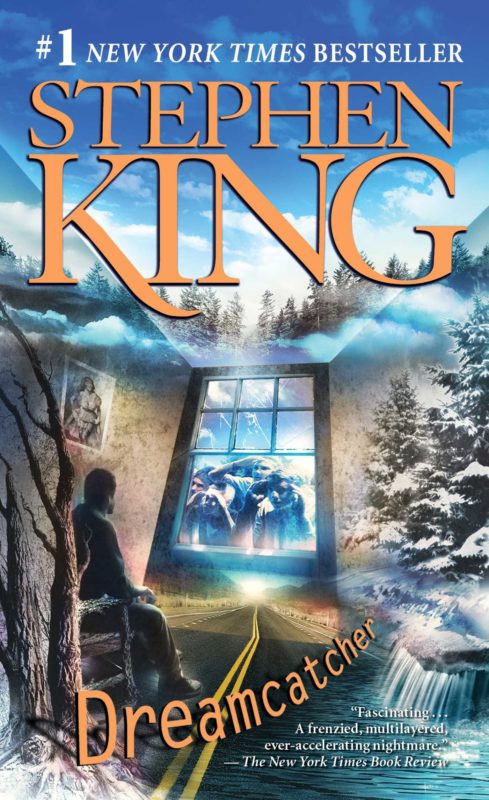

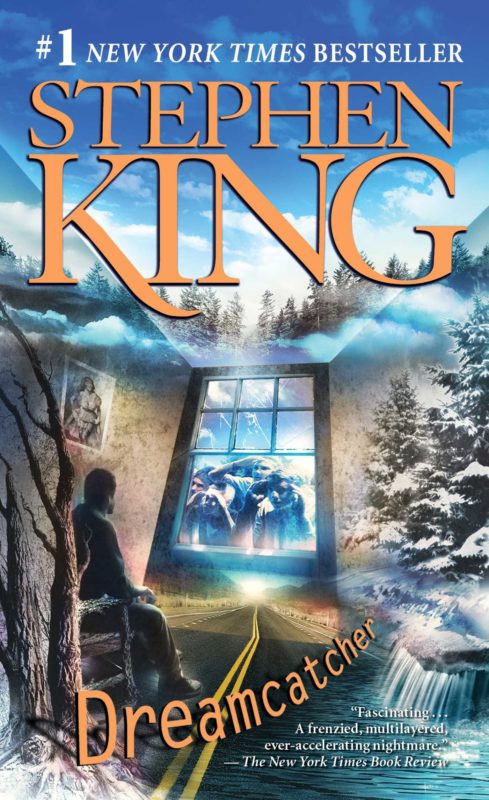

The author of Naked Lunch is heroin, with William S Burroughs a kind of scribe. Stephen King is a similar case: an amanuensis taking dictation from whatever substance he’s on. His 80s coke-written novels and tend to be manic, fast, and insane. Dreamcatcher was written in 2001 under the influence of opioids (in the aftermath of a severe car accident) and it’s slow and laboured. Reading Dreamcatcher is like walking in the dark, looking for a bus station in a part of town that might not have a bus station.

It was one of my first King books. It fairly represents his work: most of his themes and hobbyhorses are here. Big secret in a small town. Childhood innocence contrasted with adult disillusionment. Monsters. Aliens. Government spooks. Etc.

It’s set in the fictitious town of Derry, and there’s a loud reference to It along with a quieter one to Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption. It harkens back to his old work in many ways – like a reprise of a famous old song, played in half-time. I think King mostly wrote it to prove to himself that he still had it.

Four young boys rescue a retarded boy from a gang of bullies, an act so selflessly heroic they’re all but owed a supernatural reward. They grow up sharing a telepathic gift – they know things they shouldn’t know, can detect emotional states, and immediately know when someone in their group is in physical danger. Adulthood pulls them apart, but every year they gather in northern Maine for some hunting.

One year, a man shows up at their snowbound cabin. He’s lost, doesn’t know where he is, doesn’t know what day he is, and can’t cogently explain what happened to him. The reader will immediately think alien abduction, but the four main characters are slower on the uptake. The stranger soon undergoes a gruesome transformation. The four men are still on a hunting trip, but not the one they signed up for.

There’s lots of flatulence, and toilet non-humor. This is the most Cronenbergian thing King wrote; he really explores how physically disgusting it might be to have an alien incubating inside you. The subtitle might as well be “two digestive tracts, one body”.

Beaver pointed. The door to the bathroom where they’d put Rick McCarthy — Jonesy’s room — stood open. The door to the bathroom, which they had left open so McCarthy could not possibly miss his way if nature called, was now closed.

Beaver turned his somber, beard—speckled face to Jonesy’s. ‘Do you smell it?’

Jonesy did, in spite of the cold fresh air coming in through the door. Ether or ethyl alcohol, yes, there was still that, but now it was mixed with other stuff. Feces for sure. Something that could have been blood. And something else, something like mine-gas trapped a million years and finally let free. Not the kind of fart-smells kids giggled over on camping trips, in other words. This was something richer and far more awful. You could only compare it to farts because there was nothing else even close. At bottom, Jonesy thought, it was the smell of something contaminated and dying badly. ‘And look there. ‘

Beaver pointed at the hardwood floor. There was blood on it, a trail of bright droplets running from the open door to the closed one. As if McCarthy had dashed with a nosebleed. Only Jonesy didn’t think it was his nose that had been bleeding.

Much of the book is a riff on the It formula, with adults adrift in a gruesome catastrophe while remembering stuff from their childood. Sweetening alienation (literally, in this case) with nostalgia is one of King’s favorite and most effective tricks, and he puts it to good use here.

Nostalgia is a word formed out of algos, pain. There’s a lot of pain in this book. All of the four (five?) main characters suffer debilitating wounds or worse over the book’s course, and King’s own agony seems psychically imprinted on its every page. Some of the book’s most devastating moments deal with Jonesy’s memories of a car accident. It’s one of the few parts where King surfaces through a paint-by-numbers drug fog and actually seems to be connecting to something that truly matters to him.

The most vivid monster in the book isn’t an alien but a man; a flamboyant and deranged US Army Colonel called Abraham Kurtz, who throws a quarantine zone around the northern Maine woods. He’s a great character – you enjoy the moments he’s on the page, because only then is something guaranteed to happen.

The book’s problems are pretty obvious. It’s simply too slow.

Dreamcatcher is a picture all out of focus, with no idea of what the important bits of story are or how to get to them. It meanders like thorazine hallucination. You want King to get to the point, and instead he starts distractedly twirling a loose thread of narrative tapestry with his finger. We get backstory, dumped right into the middle of an exciting action moment. We get descriptions of Maine scenery just when the plot needs to be moving. The book’s comic-book gross out elements jibe awkwardly with some pop culture pretensions, like calling his lunatic “Kurtz” and then having a character draw attention to it, just in case we missed that it’s a reference to something.

I might recommend Dreamcatcher if you’re on a luxury liner for a very long time and can only take one book. I guess you can say that opioids are not really such an interesting drug to “read”. There’s a reason Scarface focused on uppers rather than downers.